Asafoetida

Asafoetida (/æsəˈfɛtɪdə/; also spelled asafetida)[1] is the dried latex (gum oleoresin) exuded from the rhizome or tap root of several species of Ferula (F. foetida and F. assa-foetida), perennial herbs growing 1 to 1.5 m (3.3 to 4.9 ft) tall. They are part of the celery family, Umbelliferae. Notably, asafoetida is thought to be in the same genus as silphium, a North African plant now believed to be extinct, and was used as a cheaper substitute for that historically important herb from classical antiquity. The species are native to the deserts of Iran and mountains of Afghanistan where substantial amounts are grown.[2] The common modern name for the plant in Iran and Afghanistan is badian, meaning: "that of gas or wind", due to its use to relieve stomach gas.

Asafoetida has a pungent smell, lending it the trivial name of stinking gum, but in cooked dishes it delivers a smooth flavour reminiscent of leeks or other onion relatives. The odor dissipates upon cooking. Asafoetida is also known variously as "food of the devils", "devil's dung", javoneh-i badian, hengu, hiltis חילתית in Aramaic[3], hing, inguva, kayam, and ting.[4]

Etymology

The English name is derived from asa, a latinised form of Persian azā, meaning "resin", and Latin foetidus meaning "smelling, fetid", which refers to its strong sulfurous odour.

In the U.S., the folk spelling and pronunciation is "asafedity". It is called perunkayam (பெருங்காயம்) in Tamil, hinga (हिंग) in Marathi, hengu (ହେଙ୍ଗୁ) in Odia, hiṅ (হিং) in Bengali, ingu (ಇಂಗು) in Kannada, kāyaṃ (കായം) in Malayalam (it was attested as raamadom in the 14th century), inguva (ఇంగువ) in Telugu, and hīng (हींग) in Hindi. In Pashto, it is called hënjâṇa (هنجاڼه).[5] Its pungent odour has resulted in its being known by many unpleasant names. In French it is known (among other names) as merde du Diable, meaning "Devil's shit".[6] In English it is sometimes called Devil's dung, and equivalent names can be found in most Germanic languages (e.g., German Teufelsdreck,[7] Swedish dyvelsträck, Dutch duivelsdrek[6], and Afrikaans duiwelsdrek). Also, in Finnish it is called pirunpaska or pirunpihka, in Turkish it is known as Şeytan tersi, Şeytan boku or Şeytan otu[6], and in Kashubian it is called czarcé łajno.

Uses

Cooking

.jpg)

This spice is used as a digestive aid, in food as a condiment, and in pickling. It plays a critical flavoring role in Indian vegetarian cuisine by acting as a savory enhancer.[8] Used along with turmeric, it is a standard component of lentil curries, such as dal, chickpea curries, and vegetable dishes, especially those based on potato and cauliflower. Asafoetida is used in vegetarian Indian Punjabi and South Indian cuisine where it enhances the flavor of numerous dishes, where it is quickly heated in hot oil before sprinkling on the food. Kashmiri cuisine also uses it in lamb/mutton dishes such as Rogan Josh.[9] It is sometimes used to harmonise sweet, sour, salty, and spicy components in food. The spice is added to the food at the time of tempering. Sometimes dried and ground asafoetida (in small quantities) can be mixed with salt and eaten with raw salad.

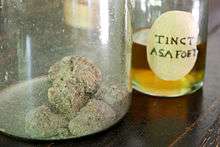

In its pure form, it is sold in the form of chunks of resin, small quantities of which are scraped off for use. The odor of the pure resin is so strong that the pungent smell will contaminate other spices stored nearby if it is not stored in an airtight container.

Cultivation and manufacture

The resin-like gum comes from the dried sap extracted from the stem and roots and is used as a spice. The resin is greyish-white when fresh, but dries to a dark amber colour. The asafoetida resin is difficult to grate and is traditionally crushed between stones or with a hammer. Today, the most commonly available form is compounded asafoetida, a fine powder containing 30% asafoetida resin, along with rice flour or maida (white wheat flour) and gum arabic.

Ferula assa-foetida is a monoecious, herbaceous, perennial plant of the family Apiaceae. It grows to 2 m (6.6 ft) high, with a circular mass of 30–40 cm (12–16 in) leaves. Stem leaves have wide sheathing petioles. Flowering stems are 2.5–3 m (8.2–9.8 ft) high and 10 cm (3.9 in) thick and hollow, with a number of schizogenous ducts in the cortex containing the resinous gum. Flowers are pale greenish yellow produced in large compound umbels. Fruits are oval, flat, thin, reddish brown and have a milky juice. Roots are thick, massive, and pulpy. They yield a resin similar to that of the stems. All parts of the plant have the distinctive fetid smell.[10]

Composition

Typical asafoetida contains about 40–64% resin, 25% endogeneous gum, 10–17% volatile oil, and 1.5–10% ash. The resin portion is known to contain asaresinotannols 'A' and 'B', ferulic acid, umbelliferone and four unidentified compounds.[11] The volatile oil component is rich in various organosulfide compounds, such as 2-butyl-propenyl-disulfide, diallyl sulfide, diallyl disulfide (also present in garlic) [12] and dimethyl trisulfide, which is also responsible for the odor of cooked onions.[13] The organosulfides are primarily responsible for the odor and flavor of asafoetida.

History

Asafoetida was familiar in the early Mediterranean, having come by land across Iran. It entered Europe from an expedition of Alexander the Great, who, after returning from a trip to northeastern ancient Persia, thought they had found a plant almost identical to the famed silphium of Cyrene in North Africa—though less tasty. Dioscorides, in the first century, wrote, "the Cyrenaic kind, even if one just tastes it, at once arouses a humour throughout the body and has a very healthy aroma, so that it is not noticed on the breath, or only a little; but the Median [Iranian] is weaker in power and has a nastier smell." Nevertheless, it could be substituted for silphium in cooking, which was fortunate, because a few decades after Dioscorides' time, the true silphium of Cyrene became extinct, and asafoetida became more popular amongst physicians, as well as cooks.[14]

Asafoetida is also mentioned numerous times in Jewish literature, such as the Mishnah.[15] Maimonides also writes in the Mishneh Torah "In the rainy season, one should eat warm food with much spice, but a limited amount of mustard and asafoetida [חִלְתִּית chiltit]."[16]

Though it is generally forgotten now in Europe, it is still widely used in India. Asafoetida is eaten by Brahmins and Jains as a substitute for onion and garlic, which they were forbidden to eat.[17]

Asafoetida was described by a number of Arab and Islamic scientists and pharmacists. Avicenna discussed the effects of asafoetida on digestion. Ibn al-Baitar and Fakhr al-Din al-Razi described some positive medicinal effects on the respiratory system.[18]

After the Roman Empire fell, until the 16th century, asafoetida was rare in Europe, and if ever encountered, it was viewed as a medicine. "If used in cookery, it would ruin every dish because of its dreadful smell," asserted Garcia de Orta's European guest. "Nonsense," Garcia replied, "nothing is more widely used in every part of India, both in medicine and in cookery. All the Hindus add it to their food."[14] During the Italian Renaissance, asafoetida was used as part of the exorcism ritual.[19]

See also

- Ammoniacum

- Chaat masala

- Muskroot

- South Asian pickles

- Turmeric – Plant used as spice

References

- "asafœtida". Oxford English Dictionary second edition. Oxford University Press. 1989. Retrieved 19 December 2018.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on January 4, 2012. Retrieved January 7, 2012.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- ben Jehiel, Nathan (1553). ספר הערוך [Sefer he-ʻArukh] (in Hebrew). Venice: Frentsuni-Bragadin.

- Literature Search Unit (January 2013). "Ferula Asafoetida: Stinking Gum. Scientific literature search through SciFinder on Ferula asafetida". Indian Institute of Integrative Medicine. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Pashto-English Dictionary

- Asafoetida: die geur is des duivels! Vegatopia (in Dutch), Retrieved 8 December 2011. This used as source the book World Food Café: global vegetarian cooking by Chris and Carolyn Caldicott, 1999, ISBN 978-1-57959-060-4

- Thomas Carlyle's well-known 19th century novel Sartor Resartus concerns a German philosopher named Teufelsdröckh.

- Carolyn Beans. Meet Hing: The Secret-Weapon Spice Of Indian Cuisine.June 22, 2016. https://www.npr.org/sections/thesalt/2016/06/22/482779599/meet-hing-the-secret-weapon-spice-of-indian-cuisine

- Kashmiri Recipes; Mutton Rogan Josh. It is essential to many many south Indian dishes. http://www.polkacafe.com/authentic-kashmiri-recipes-2524.html Archived 2018-12-11 at the Wayback Machine

- Ross, Ivan A. (2005). "Ferula assafoetida". Medicinal Plants of the World, Volume 3. pp. 223–234. doi:10.1007/978-1-59259-887-8_6. ISBN 978-1-58829-129-5.

- Handbook of Indices of Food Quality and Authenticity. Rekha S. Singhal, Pushpa R. Kulkarni. 1997, Woodhead Publishing, Food industry and trade ISBN 1-85573-299-8. More information about the composition, p. 395.

- Mahendra, P; Bisht, S (2012). "Ferula asafoetida: Traditional uses and pharmacological activity". Pharmacogn Rev. 6: 141–6. doi:10.4103/0973-7847.99948. PMC 3459456. PMID 23055640.

- Asafoetida. Katrina Kramer. Royal Society of Chemistry Podcast. 22 June 2016. https://www.chemistryworld.com/podcasts/asafoetida/1010150.article

- Dangerous Tastes: The Story of Spices. Andrew Dalby. 2000. University of California Press. Spices/ History. 184 pages. ISBN 0-520-23674-2

- m. Avodah Zarah ch. 1; m. Shabbat ch. 20; et al.

- Mishneh Torah, Laws of Opinions (Hilchot Deot) 4:8.

- Pickersgill, Barbara (2005). Prance, Ghillean; Nesbitt, Mark (eds.). The Cultural History of Plants. Routledge. p. 157. ISBN 0415927463.

- Avicenna (1999). The Canon of Medicine (al-Qānūn fī'l-ṭibb), vol. 1. Laleh Bakhtiar (ed.), Oskar Cameron Gruner (trans.), Mazhar H. Shah (trans.). Great Books of the Islamic World. ISBN 978-1-871031-67-6

- Menghi, Girolamo. The Devil's Scourge: Exorcism During the Italian Renaissance. p. 151.