Art Institute of Chicago Building

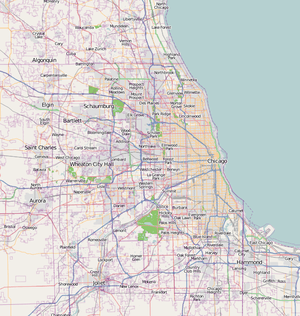

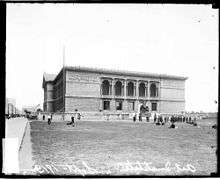

The Art Institute of Chicago Building (1893 structure built as the World's Congress Auxiliary Building) houses the Art Institute of Chicago, and is part of the Chicago Landmark Historic Michigan Boulevard District in the Loop community area of Chicago, Illinois. The building is located in Grant Park on the east side of Michigan Avenue, and marks the third address for the Art Institute. The building was built for the joint purpose of providing an additional facility for the 1893 World's Columbian Exposition, and subsequently the Art Institute. The core of the current complex, located opposite Adams Street, officially opened to the public on December 8, 1893,[1] and was renamed the Allerton Building in 1968.

| Art Institute of Chicago Building | |

|---|---|

View from Adams Street | |

| |

| General information | |

| Architectural style | Beaux-Arts |

| Location | Chicago, Illinois |

| Country | United States |

| Coordinates | 41°52′46.56″N 87°37′25.32″W |

| Construction started | 1893 |

| Design and construction | |

| Architect | Shepley, Rutan and Coolidge |

There have been numerous building additions over the years. The most recent addition is the Modern Wing funded in part by Pat Ryan.[2] This new building increases gallery space by 33% and accommodates new educational facilities. It opened to the public on May 16, 2009.[3][4]

Buildings

History

.tiff.jpg)

The Art Institute of Chicago opened as the Chicago Academy of Fine Arts on May 24, 1879, and changed to its current name on December 23, 1882.[5] It was originally established as both a school and museum, and stood on the southwest corner of Michigan Avenue and Monroe Street,[6] where it rented space.[7] Before taking over its current building it occupied a four-story Romanesque building designed by Burnham & Root at 81 East Van Buren Street, where the Chicago Club is now situated.[8][9] The Art Institute, which moved there at the time it changed names, originally leased and later purchased the space.[7] With the coming of the 1893 World's Columbian Exposition and its need for a new home for its expanding collection and growing student body, the Art Institute's trustees negotiated for a new structure at what has come to be the current building.[1] Although Aaron Montgomery Ward opposed the development of Grant Park with public buildings along the lakefront, he did not oppose the Art Institute.[10]

The new building was funded by the sale of the Van Buren Street building to the Chicago Club for $ 265,000, by donation of the land by the Chicago Park District, by $120,000 public subscription, and by $200,000 contribution of the Fair Corporation in cooperation with the Exposition.[7] The World Congress Auxiliary of the World's Columbian Exposition occupied the new building from May 1 to October 31, 1893, after which the Art Institute took possession on November 1.[7] The building was built in the place of William W. Boyington's Illinois Interstate Exposition Building (1873), which had been intended as a temporary structure.[11]

Upon his death in 1905, lumber merchant Benjamin Franklin Ferguson bequeathed almost $1 million (equivalent to $28,455,556 in 2019) for the purpose of establishing a public sculpture fund to be administered by the Art Institute.[12] The first gift from this memorial fund was the Fountain of the Great Lakes, which was commissioned in 1907.[13]

Architecture

The current building is a classical Beaux-Arts building, by Shepley, Rutan and Coolidge of Boston, Massachusetts.[1] The Fullerton Auditorium and Ryerson Library were added to the building in 1898 and 1901 respectively.[1] The building is composed of 273 galleries that total 562,000 square feet (52,200 m2).[5] The following is a summary of all additions.[14] The building has a grand Italian Renaissance facade with a pedimented 5-bayed central section that protrudes forward from the 7-bayed wings on either side.[15] The arcaded entry loggia is topped by three grand palladian arches that are separated by Corinthian half-columns.[15]

| Addition | Architect | Year |

|---|---|---|

| Ryerson & Burnham Libraries | Shepley, Rutan & Coolidge | 1901 |

| McKinlock Court | Coolidge & Hodgdon | 1924 |

| Goodman Theater | Howard Van Doren Shaw | 1926 |

| Ferguson Building | Holabird & Root & Burgee | 1958 |

| Morton Wing | Shaw, Metz, & Assoc. | 1962 |

| Columbus Drive Addition and School of the Art Institute | Skidmore, Owings & Merrill | 1977 |

| Daniel F. & Ada Rice Building | Hammond, Beeby & Babka | 1988 |

| Fullerton Hall Restoration | Weese Langley Weese: Gilmore, Franzen Architects | 2001 |

| Modern Wing | Renzo Piano | 2009 |

Fullerton Hall was originally built in 1898 by Shepley, Rutan & Coolidge on the north side of the main floor in place of a formerly open court.[16] It was built to seat an audience of 425.[16] It has a stained glass dome and formerly had a crystal chandelier both made by Louis Comfort Tiffany.[16]

Ryerson Library was built in 1901 to the south opposite Fullerton Hall in another open court by Shepley, Rutan & Coolidge.[16] The Burnham Library of Architecture, which opened on January 12, 1920, was added south of and adjacent to the Ryerson Library by Howard Van Doren Shaw.[17]

The Grand Staircase was completed in 1910. However, the architectural ornamentation of the neighboring gallery continued intermittently until 1929 without ever being completed. Plans for a great dome over this staircase were abandoned when proper financing never arose.[18]

In 1916, Gunsaulus Hall was built by Shepley, Rutan & Coolidge as a two-story bridge addition spanning the Illinois Central Railroad tracks behind the original building.[13]

McKinlock Court was landscaped in 1924.[17] By 1931 the court was remodeled so the Fountain of the Tritons could be installed.[19] Today, this court is open for dining during summer months and still contains the Carl Milles bronze fountain in its center.[14][15]

In 1958, Blackstone Hall, which had been added adjacent to the east wall of the original building in 1903 and once housed over 150 plaster casts of architectural artwork,[20][21] was redesigned (further redesign continued in 1959). After the redesign Blackstone Hall no longer exhibited the Greek and Roman, Renaissance and modern sculptures.[22] Now the Hall is partitioned into several galleries. Also in 1958, the Benjamin F. Ferguson Memorial Building was constructed by Holabird & Root & Burgee to accommodate administrative and curatorial offices, which relieved space in the existing buildings for more gallery space.[23]

In 1960, the Stanley McCormick Memorial Court (north garden) was constructed by Holabird & Root & Burgee.[24] The south garden was constructed in 1965, when the Fountain of the Great Lakes was moved and reinstalled.[25] Dan Kiley designed the South garden.[26]

In 1962, The Morton Wing was added south of the central building to provide additional exhibition space and galleries. This balanced the Ferguson building by restoring symmetry.[24][27]

In 1968, the original central building was named the Allerton Building after longtime trustee Robert Allerton.[27]

In the 1970s, the growth of the school and visitor attendance necessitated the Rubloff Building to accommodate new studios, classrooms, and a film center for the school, and new public spaces for the museum.[27] Ground was broken in 1974, and the dedication was held October 6, 1976.[28]

The Adler & Sullivan-designed Chicago Stock Exchange Building (1893–1972) Trading Room was salvaged from demolition and installed in the Columbus Drive Addition in 1977. This building fragment, which includes Louis Sullivan's exquisite stenciling, is described as the "Wailing Wall of Chicago preservationists".[14]

In 1988, the Daniel F. and Ada L. Rice Building, designed by Driehaus Prize winner Thomas H. Beeby, was added to show the dramatically increased contemporary art collection and to exhibit popular large traveling exhibitions.[29]

Modern Wing

The Modern Wing, opened in 2009, was designed by Renzo Piano and funded in part by Pat Ryan. It increases the museum's gallery space by 30 percent by adding 65,000 square feet (6,000 m2) of new galleries, and includes the 15,000 square feet (1,400 m2) Ryan Education Center on the first floor. [2][30] The new building incorporates cutting-edge green technologies, such as a modern sunshade to filter daylight. [31] The sunshade, dubbed "The Flying Carpet", is made of white extruded aluminum and is linked to the lighting system to adjust and compensate for incandescent fixtures.[32] The Nichols Bridgeway, a 625-foot (190 m) pedestrian bridge also designed by Piano, links the building to Millennium Park.

Entrance

Flanking the exterior Michigan Avenue entrance stairs are two bronze lions by sculptor Edward Kemeys that were a gift from a Mrs. Henry Field for the Art Institute's opening at its current location in 1893. Although the lions have no official names, the sculptor designated the lions by their poses as "stands in an attitude of defiance" (south lion) and "on the prowl" (north lion).[33] These lions, along with those pairs in front of the New York Public Library Main Branch on Fifth Avenue and the pair in the grand staircase of the Boston Public Library's Central Library, are part of an Italian Renaissance revival by 19th-century Romantic artists.[34] Guardian lions had been an important architectural theme of the World Columbian Exposition, where six pairs guarded the entrance of the Palace of Fine Arts. Kemeys had sculpted one of these pairs, which may have served as his model for the Art Institute lions.[35] The lions were moved back 12 feet (3.7 m) toward the museum in 1909-10 in conjunction with the widening of Michigan Avenue and the addition of a balustrade and terrace to the south, west and north sides of the building.[20]

When a Chicago sports team makes the playoffs, the lions are frequently dressed in that team's uniform. This has been done for the Chicago White Sox in 2005, the Chicago Bears in 1986 and 2007, the Chicago Blackhawks in 2010, and the Chicago Cubs in 2016.

Notes

- "1879-1913: The Formative Years". The Art Institute of Chicago. 2007. Archived from the original on June 9, 2007. Retrieved June 20, 2007.

- "Latest News". The Art Institute of Chicago. 2007. Archived from the original on June 9, 2007. Retrieved June 26, 2007.

- "The Building". The Art Institute of Chicago. 2007. Archived from the original on June 9, 2007. Retrieved June 26, 2007.

- "The Art Institute of Chicago: Modern Wing". Art Institute of Chicago. Archived from the original on December 28, 2008. Retrieved January 11, 2009.

- "Art Institute of Chicago: Fact Sheet," January 2007 edition, distributed at information desk.

- "History". The Art Institute of Chicago. 2007. Archived from the original on June 9, 2007. Retrieved June 20, 2007.

- "The Art Institute of Chicago Museum Studies'" p. 8.

- Sinkevitch, p. 44.

- Steiner, p. 9.

- Sinkevitch, p. 14.

- "The Art Institute of Chicago Museum Studies'" pp. 33-4.

- Sinkevitch, p. 291.

- "The Art Institute of Chicago Museum Studies'" p. 14.

- Sinkevitch, p. 41.

- Steiner, p. 10.

- "The Art Institute of Chicago Museum Studies'" p. 9.

- "The Art Institute of Chicago Museum Studies'" p. 16.

- "The Art Institute of Chicago Museum Studies'" p. 13.

- "The Art Institute of Chicago Museum Studies'" p. 17.

- "The Art Institute of Chicago Museum Studies'" p. 10.

- Harris, p. 16.

- Harris, p. 17.

- "The Art Institute of Chicago Museum Studies'" p. 18.

- "The Art Institute of Chicago Museum Studies'" p. 19.

- "The Art Institute of Chicago Museum Studies'" p. 20.

- Macaluso, Tony; Julia S. Bachrach & Neal Samors (2009). Sounds of Chicago's Lakefront: A Celebration Of The Grant Park Music Festival. Chicago's Book Press. p. 42. ISBN 978-0-9797892-6-7.

- "1955-1977: Expansion Mid-Century". The Art Institute of Chicago. 2007. Archived from the original on June 9, 2007. Retrieved June 25, 2007.

- "The Art Institute of Chicago Museum Studies'" p. 21.

- "1985-2000: End of The Century". The Art Institute of Chicago. 2007. Archived from the original on June 9, 2007. Retrieved June 25, 2007.

- "Reinstallation". The Art Institute of Chicago. 2007. Retrieved June 26, 2007.

- "Design and Construction". The Art Institute of Chicago. 2007. Retrieved June 26, 2007.

- "Building Engineering". The Art Institute of Chicago. 2007. Archived from the original on June 10, 2007. Retrieved June 26, 2007.

- "FAQs". The Art Institute of Chicago. 2007. Archived from the original on June 9, 2007. Retrieved June 20, 2007.

- "The Art Institute of Chicago Museum Studies'" pp 47-8.

- "The Art Institute of Chicago Museum Studies'" pp. 51-2.

References

- Harris, Neil, "Chicago's Dream, a World's Treasure," 1993, The Art Institute of Chicago, ISBN 0-86559-121-0

- Sinkevitch, Alice, "AIA Guide to Chicago" (2nd edition), 2004, Harcourt Books, ISBN 0-15-602908-1

- Steiner, Frances H., "The Architecture of Chicago's Loop", 1998, Sigma Press, ISBN 0-9667259-0-5

- "The Art Institute of Chicago Museum Studies'" Volume 14, no. 1, 1988, The Art Institute of Chicago, ISBN 0-226-02813-5

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Art Institute of Chicago Building. |