Flying buttress

The flying buttress (arc-boutant, arch buttress) is a specific form of buttress composed of an arch that extends from the upper portion of a wall to a pier of great mass, in order to convey to the ground the lateral forces that push a wall outwards, which are forces that arise from vaulted ceilings of stone and from wind-loading on roofs.[1]

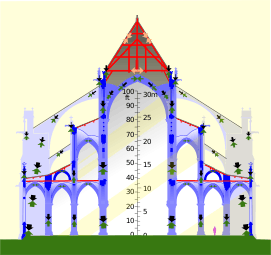

The defining, functional characteristic of a flying buttress is that it is not in contact with the wall at ground level, unlike a traditional buttress, and so transmits the lateral forces across the span of intervening space between the wall and the pier. To provide lateral support, flying-buttress systems are composed of two parts: (i) a massive pier, a vertical block of masonry situated away from the building wall, and (ii) an arch that bridges the span between the pier and the wall — either a segmental arch or a quadrant arch — the flyer of the flying buttress.[2]

History

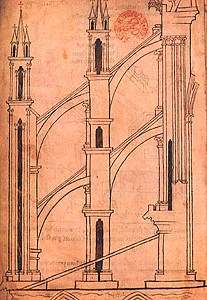

As a lateral-support system, the flying buttress was developed during late antiquity and later flourished during the Gothic period (12th–16th c.) of architecture. Ancient examples of the flying buttress can be found on the Basilica of San Vitale in Ravenna and on the Rotunda of Galerius in Thessaloniki. The architectural-element precursors of the medieval flying buttress derive from Byzantine architecture and Romanesque architecture, in the design of churches, such as Durham Cathedral, where arches transmit the lateral thrust of the stone vault over the aisles; the arches were hidden under the gallery roof, and transmitted the lateral forces to the massive, outer walls. By the decade of 1160, architects in the Île-de-France region employed similar lateral-support systems that featured longer arches of finer design, which run from the outer surface of the clerestory wall, over the roof of the side aisles (hence are visible from the outside) to meet a heavy, vertical buttress rising above the top of the outer wall.[3]

The flying buttresses of Notre Dame de Paris, constructed in 1180, were among the earliest to be used in a Gothic cathedral. Flying buttresses were also used at about the same time to support the upper walls of the apse at the Church of Saint-Germain-des-Prés, completed in 1163. [4]

The advantage of such lateral-support systems is that the outer walls do not have to be massive and heavy in order to resist the lateral-force thrusts of the vault. Instead, the wall surface could be reduced (allowing for larger windows, glazed with stained glass), because the vertical mass is concentrated onto external buttresses. The design of early flying buttresses tended to be heavier than required for the static loads to be borne, e.g. at Chartres Cathedral (ca. 1210), and around the apse of the Saint Remi Basilica, which is an extant, early example in its original form (ca. 1170).[5] Later architects progressively refined the design of the flying buttress, and narrowed the flyers, some of which were constructed with one thickness of voussoir (wedge brick) with a capping stone atop, e.g. at Amiens Cathedral, Le Mans Cathedral, and Beauvais Cathedral.

The architectural design of Late Gothic buildings featured flying buttresses, some of which featured flyers decorated with crockets (hooked decorations) and sculpted figures set in aedicules (niches) recessed into the buttresses. In the event, the architecture of the Renaissance eschewed the lateral support of the flying buttress in favour of thick-wall construction. Despite its disuse for function and style in construction and architecture, in the early 20th century, the flying-buttress design was revived by Canadian engineer William P. Anderson to build lighthouses.[6]

Construction

_(14597612677).jpg)

Given that most of the weight-load is transmitted from the ceiling through the upper part of the walls, the flying buttress is a two-part composite support that features a semi-arch that extends to a massive pier far from the wall, and so provides most of the load-bearing capacity of a traditional buttress, which is engaged with the wall from top to bottom; thus, the flying buttress is a lighter and more cost-effective architectural structure.

By relieving the load-bearing walls of excess weight and thickness, in the way of a smaller area of contact, using flying buttresses enables installing windows in a greater wall surface area. This feature and a desire to let in more light, led to flying buttresses becoming one of the defining factors of medieval Gothic architecture and a feature used extensively in the design of churches from then and onwards. In the design of Gothic churches, two arched flyers were applied, one above the other, in which the lower flyer (positioned below the springing point of the vault) resists the lateral-thrust forces of the vault, whilst the upper flyer resists the forces of wind-loading on the roof.[7] The vertical buttresses (piers) at the outer end of the flyers usually were capped with a pinnacle (either a cone or a pyramid) usually ornamented with crockets, to provide additional vertical-load support with which to resist the lateral thrust conveyed by the flyer.[8]

To build the flying buttress, it was first necessary to construct temporary wooden frames, which are called centring. The centering would support the weight of the stones and help maintain the shape of the arch until the mortar was cured. The centering was first built on the ground, by the carpenters. Once that was done, they would be hoisted into place and fastened to the piers at the end of one buttress and at the other. These acted as temporary flying buttresses until the actual, stone arch was complete.[9]

- Remedial support application

Another application of the flying-buttress support system is the reinforcement of a leaning wall in danger of collapsing, especially a load-bearing wall; for example, at the village of Chaddesley Corbett in Worcestershire, England, the practical application of a flying buttress to a buckled wall is more practical than dismantling and rebuilding the wall.

Aesthetic style of the Gothic period

The desire to build large cathedrals that could house many followers along multiple aisles arose, and from this desire the Gothic style developed.[10] The flying buttress was the solution to these massive stone buildings that needed a lot of support but wanted to be expansive in size. Although the flying buttress originally served a structural purpose, they are now a staple in the aesthetic style of the Gothic period.[11] The flying buttress originally helped bring the idea of open space and light to the cathedrals through stability and structure, by supporting the clerestory and the weight of the high roofs.[11] The height of the cathedrals and ample amount of windows among the clerestory creates this open space for viewers to see through, making the space appear more continuous and giving the illusion of there being no clear boundaries.[11]

It also makes the space more dynamic and less static separating the Gothic style from the flatter more two dimensional Romanesque style.[11] After the introduction of the flying buttress this same concept could be seen on the exterior of the cathedrals as well.[11] There is open space below the arches of the flying buttress and this space has the same effect as the clerestory within the church allowing the viewer to view through the arches, the buttresses also reach into the sky similar to the pillars within the church which creates more upward space.[11] Making the exterior space equally as dynamic as the interior space and creating a sense of coherence and continuity.[12]

Gallery of flying buttresses

Notre Dame of Paris

Notre Dame of Paris One of the very ornate flying buttresses of St. John's Cathedral, 's-Hertogenbosch, The Netherlands

One of the very ornate flying buttresses of St. John's Cathedral, 's-Hertogenbosch, The Netherlands In the basilica built ca. AD 1170 at the Abbey of Saint-Remi, in France a flying buttress system is used for lateral-support

In the basilica built ca. AD 1170 at the Abbey of Saint-Remi, in France a flying buttress system is used for lateral-support Saint Rose of Viterbo Church, Santiago de Queretaro, Queretaro, Mexico

Saint Rose of Viterbo Church, Santiago de Queretaro, Queretaro, Mexico Tower of St Peter and St Paul's Church, Easton Maudit, England

Tower of St Peter and St Paul's Church, Easton Maudit, England Lincoln Cathedral, England

Lincoln Cathedral, England.jpg) Saint-Petrus-en-Pauluskerk, Ostend, Belgium

Saint-Petrus-en-Pauluskerk, Ostend, Belgium- Bath Abbey, England

Amiens Cathedral, Amiens, France

Amiens Cathedral, Amiens, France

_PT_en.svg.png) Flying buttresses in cross-section

Flying buttresses in cross-section

In fiction

The architecture and construction of a medieval cathedral with flying buttresses figures prominently into the plot of the historical novel The Pillars of the Earth by Ken Follett (1989).

See also

- Buttress

- Cathedral architecture

- Flying arch

- Gothic architecture

- Seismic retrofit

Notes

- Curls, James Stevens, ed. (1999). A Dictionary of Architecture. Oxford. pp. 113–114.

- For the functional mechanics of the flying buttresses, see Borg, Alan; Mark, Robert (1973). "Chartres Cathedral: A Reinterpretation of its Structure". The Art Bulletin. 55 (3): 367–372. doi:10.1080/00043079.1973.10790710.

- James, John (September 1992). "Evidence for flying buttresses before 1180". J. Soc. Archit. Hist. 51 (3): 261–287. doi:10.2307/990687.

- Watkin, David, "A History of Wesern Architecture" (1986), page 130

- Prache, Anne (1976). "Les Arcs - boutants au XIIe siècle". Gesta. 15 (1): 31–42. doi:10.2307/766749.

- Russ Rowlett, Canadian Flying Buttress Lighthouses, in The Lighthouse Directory.

- Mark, R.; Jonash, R. S. (1970). "Wind Loads on Gothic Structures". Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians. 29 (3): 222–230. doi:10.2307/988611.

- Curls, James Stevens, ed. (1999). A Dictionary of Architecture. Oxford. p. 501.

- Alex Lee, James Arndt, and Shane Goldmacher, Cathedral Architecture Archived 2005-08-29 at the Wayback Machine.

- Moore, Charles H. (1979). Development + & and character of gothic architecture. Longwood. pp. 19-20. ISBN 0893413585. OCLC 632226040.

- Frankl, Paul (1962). Gothic Architecture. Baltimore: Penguin Books. pp. 54–57.

- Mark, Robert (2014). Experiments in Gothic Structure. Bibliotheque McLean. ISBN 0955886864. OCLC 869186029.

References

- Watkin, David (1986). A History of Western Architecture. Barrie and Jenkins. ISBN 0-7126-1279-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Flying buttresses. |

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.