Santa Maria in Ara Coeli

The Basilica of St. Mary of the Altar of Heaven (Latin: Basilica Sanctae Mariae de Ara coeli in Capitolium, Italian: Basilica di Santa Maria in Ara coeli al Campidoglio) is a titular basilica in Rome, located on the highest summit of the Campidoglio. It is still the designated Church of the city council of Rome, which uses the ancient title of Senatus Populusque Romanus. The present Cardinal Priest of the Titulus Sanctae Mariae de Aracoeli is Salvatore De Giorgi.

| Basilica of St. Mary of the Altar of Heaven Basilica di Santa Maria in Aracoeli (in Italian) Basilica Sanctae Mariae de Ara coeli (in Latin) | |

|---|---|

Façade of the Basilica with the monumental staircase. | |

| Religion | |

| Affiliation | Roman Catholic |

| Ecclesiastical or organizational status | Minor basilica |

| Leadership | Salvatore De Giorgi |

| Location | |

| Location | Rome, Italy |

| Geographic coordinates | 41°53′38″N 12°29′00″E |

| Architecture | |

| Type | Church |

| Style | Romanesque, Gothic |

| Completed | 12th century |

| Specifications | |

| Direction of façade | West by South |

| Length | 80 metres (260 ft) |

| Width | 45 metres (148 ft) |

| Width (nave) | 20 metres (66 ft) |

| Website | |

| Official Website | |

The shrine is known for housing relics belonging to Saint Helena, mother of Emperor Constantine, various minor relics from the Holy Sepulchre, both the canonically crowned images of Nostra Signora di Mano di Oro di Aracoeli (1636) on the high altar and the Santo Bambino of Aracoeli (1897).

History

Originally the church was named Sancta Maria in Capitolio, since it was sited on the Capitoline Hill (Campidoglio, in Italian) of Ancient Rome; by the 14th century it had been renamed. A medieval legend included in the mid-12th-century guide to Rome, Mirabilia Urbis Romae, claimed that the church was built over an Augustan Ara primogeniti Dei, in the place where the Tiburtine Sibyl prophesied to Augustus the coming of the Christ. "For this reason the figures of Augustus and of the Tiburtine sibyl are painted on either side of the arch above the high altar" (Lanciani chapter 1). A later legend substituted an apparition of the Virgin Mary.[1]

In The History of Money, anthropologist Jack Weatherford goes into some detail about the church's previous incarnation as the temple of Juno Moneta—on the Arx—after whom Money is named.

According to Roman historians, in the fourth century B.C., the irritated honking of the sacred geese around Juno's temple on Capitoline Hill warned the people of an impending night attack by the Gauls, who were secretly scaling the walls of the citadel. From this event, the goddess acquired [the] surname-Juno Moneta, from Latin monere (to warn). . .As patroness of the state, Juno Moneta presided over various activities of the state, including the primary activity of issuing money.

. . . from Moneta came the modem English words mint and money and, ultimately, from the Latin word meaning warning.

Today, the site of the Temple of Juno Moneta, the source of the great stream of Roman currency, has given way to the ancient . . . brick church of Santa Maria in Aracoeli. Centuries ago, church architects incorporated the ruins of the ancient temple into the new building.[2]

The church is also thought to have replaced the auguraculum, the seat of the augurs.

The foundation of the church was laid on the site of a Byzantine abbey mentioned in 574. Many buildings were built around the first church; in the upper part they gave rise to a cloister, while on the slopes of the hill a little quarter and a market grew up. Remains of these buildings - such as the little church of San Biagio de Mercato and the underlying "Insula Romana") - were discovered in the 1930s. At first the church followed the Greek rite, a sign of the power of the Byzantine exarch. Taken over by the papacy by the 9th century, the church was given first to the Benedictines, then, by papal bull to the Franciscans in 1249–1250;[1] under the Franciscans it received its Romanesque-Gothic aspect. The arches that divide the nave from the aisles are supported on columns, no two precisely alike, scavenged from Roman ruins.

During the Middle Ages, this church became the centre of the religious and civil life of the city. in particular during the republican experience of the 14th century, when self-proclaimed Tribune and reviver of the Roman Republic Cola di Rienzo inaugurated the monumental stairway of 124 steps in front of the church, designed in 1348 by Simone Andreozzi, on the occasion of the Black Death. Condemned criminals were executed at the foot of the steps; there Cola di Rienzo met his death, near the spot where his statue commemorates him.

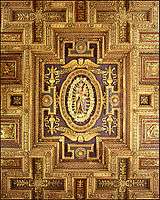

In 1571, Santa Maria in Aracoeli hosted the celebrations honoring Marcantonio Colonna after the victorious Battle of Lepanto over the Turkish fleet. Marking this occasion, the compartmented ceiling was gilded and painted (finished 1575), to thank the Blessed Virgin for the victory. In 1797, with the Roman Republic, the basilica was deconsecrated and turned into a stable.

Interior

The original unfinished façade has lost the mosaics and subsequent frescoes that originally decorated it, save a mosaic in the tympanum of the main door, one of three doors that are later additions. The Gothic window is the main detail that tourists can see from the bottom of the stairs, but it is the sole truly Gothic detail of the church.

The church is built as a nave and two aisles that are divided by Roman columns, all different, taken from diverse antique monuments.[1] Among its numerous treasures are Pinturicchio's 15th-century frescoes depicting the life of Saint Bernardino of Siena in the Bufalini Chapel, the first chapel on the right. Other features are the wooden ceiling, the inlaid cosmatesque floor, a Transfiguration painted on wood by Girolamo Siciolante da Sermoneta, and works by other artists like Pietro Cavallini (of his frescoes only one survives), Benozzo Gozzoli and Giulio Romano.

It houses also Madonna Aracoeli (Our Lady of the Golden Hands), (Byzantian icon, the 10-11th-century) in the Altar. This Marian image was Pontifically crowned on 29 March 1636 by Pope Urban VIII. Pope Pius XII consecrated the people of Rome to the Most Blessed Virgin Mary and her Immaculate Heart in front of this image in 1948, May 30. In the transept there is a sepulchral monument by Arnolfo di Cambio. The church was also famous in Rome for the wooden statue of the Santo Bambino of Aracoeli, carved in the 15th century of olive wood coming from the Gethsemane garden and covered with valuable ex-votos. Many people of Rome believed in the power of this statue. It had been taken by the French in 1797, was later recovered, yet stolen again in February 1994. A copy was made from Gethsemane wood,[3] which is now displayed in its own chapel by the sacristy. At midnight Mass on Christmas Eve the image is brought out to a throne before the high altar and unveiled at the Gloria. Until Epiphany the jewel-encrusted image resides in the Nativity crib in the left nave.

The relics of Saint Helena, mother of Constantine the Great are housed at Santa Maria in Aracoeli, as is the tablet with the monogram of Jesus that Saint Bernardino of Siena used to promote devotion to the Holy Name of Jesus is kept in Aracoeli.

Burials

- Catherine of Bosnia, Bosnian Queen

- Pope Honorius IV

- Brother Juniper, one of the original followers of Saint Francis of Assisi

- Giulio Salvadori, the poet tomb is within the church.

Curiosities

- The church also contains the marble tomb of Cecchino Bracci, pupil of artist Michelangelo who had dedicated a number of poems in his name. The tomb's design (not the carving) is by Michelangelo.

- A part of the last mission of the videogame Assassin's Creed: Brotherhood takes place in this basilica.

- In this church, football player Francesco Totti and Ilary Blasi celebrated their marriage in 2005, followed by thousands of fans.[4]

- It was this church where Edward Gibbon was struck with the idea to write his “Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire”. "It was at Rome, on the 15th of October 1764," he wrote in his "Autobiography", "as I sat musing amid the ruins of the capitol, while the bare-footed friars were singing vespers in the temple of Jupiter [Gibbon was mistaken; this church was actually the former Temple of Juno Moneta], that the idea of writing the decline and fall of the city first started to my mind.” [5]

See also

References

- Lang, Peter. "Santa Maria in Aracoeli", University of Washington

- Weatherford, Jack McIver (1997). The History of Money: From Sandstone to Cyberspace. New York: Three Rivers Press. p. 48. ISBN 9780609801727.

- Ingrid D. Rowland (2012) Anachronic Renaissance, Konsthistorisk tidskrift/ Journal of Art History, 81:3, 172-177, DOI: 10.1080/00233609.2012.706234

- Farrell, Paul (27 May 2017). "Ilary Blasi, Francesco Totti's Wife: 5 Fast Facts You Need to Know". Heavy.com. Retrieved 29 May 2018.

- https://catholicunderthehood.com/category/italian-history/

Bibliography

- Johanna Elfriede Louise Heideman, The cinquecento chapel decorations in S. Maria in Aracoeli in Rome, Academische Pers, 1982.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Santa Maria in Aracoeli. |