Al-Ram

Al-Ram, A-Ram, Er Ram or al-Ramm (Arabic: الرّام) is a Palestinian town which lies northeast of Jerusalem, just outside the city's municipal border. The village is part of the built-up urban area of Jerusalem, the Atarot industrial zone and Beit Hanina lie to the west, and Neve Ya'akov borders it on the south.[2] with a built-up area of 3,289 dunums. According to the Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics, a-Ram had a population of 25,595 in 2006.[3] The head of a-Ram village council estimates that 58,000 people live there, more than half of them holding Israeli identity cards.[4]

A-Ram | |

|---|---|

Municipality type B | |

| Arabic transcription(s) | |

| • Arabic | الرّام |

| • Latin | al-Ramm (official) al-Ram (unofficial) |

Al-Ram in the background | |

A-Ram Location of A-Ram within Palestine | |

| Coordinates: 31°51′13″N 35°14′00″E | |

| Palestine grid | 172/140 |

| State | State of Palestine |

| Governorate | Jerusalem |

| Government | |

| • Type | Municipality |

| Area | |

| • Total | 3,289 dunams (3.3 km2 or 1.3 sq mi) |

| Population (2006) | |

| • Total | 25,595 |

| • Density | 7,800/km2 (20,000/sq mi) |

| Name meaning | "The Hill"/"Stagnant water"[1] |

History

Ancient Israel

Al-Ram is thought to be the site of the biblical city of Ramah in Benjamin.[5][6][7]

Crusader period

In Crusader sources, Al-Ram was named Aram, Haram, Rama, Ramatha, Ramitta, or Ramathes.[8] Al-Ram was one of 21 villages given by King Godfrey (r. 1099–1100) as a fief to the Church of the Holy Sepulchre.[9][10] All the inhabitants of the village who were mentioned in Crusader sources between 1152 and 1160 had names which imply they were Christian.[11][12] The village was mentioned around 1161, when a dispute about a land boundary was settled.[12][13]

Ottoman period

In 1517, the village was included in the Ottoman empire with the rest of Palestine, and in the 1596 tax-records it appeared as Rama, located in the Nahiya of Jabal Quds of the Liwa of Al-Quds. The population was 28 households, all Muslim. They paid a fixed tax-rate of 33,3% on agricultural products, including wheat, barley, olive trees and vineyards, in addition to occasional revenues, goats and beehives; a total of 4700 akçe.[14]

In 1838 Edward Robinson found the village to be very poor and small, but large stones and scattered columns indicated that it had previously been an important place.[5] In 1870 the French explorer Victor Guérin found the village to have 200 inhabitants,[15] while an Ottoman village list of about the same year showed that Al-Ram had 32 houses and a population of 120, though the population count included men only.[16][17]

In 1883, the PEF's Survey of Western Palestine described Er Ram as a "small village in a conspicuous position on the top of a white hill, with olives. It has a well to the south. [..] The houses are of stone, partly built of old material".[18] "West of the village is a good birkeh with a pointed vault; lower down the hill a pillar-shaft broken in two, probably from the church. On the hill are cisterns. Drafted stones are used up in the village walls. At Khan er Ram, by the main road, is a quarry with half-finished blocks still in it, and two cisterns. The Khan appears to be quite modern, and is in ruins. There are extensive quarries on the hill-sides near it."[19]

In 1896 the population of Er-Ram was estimated to be about 240 persons.[20]

British Mandate period

In the 1922 census of Palestine conducted by the British Mandate authorities, Ram had a population 208, all Muslims.[21] This had increased in the 1931 census to 262, still all Muslim, in 51 houses.[22] Al-Ram suffered badly in the 1927 earthquake, with old walls collapsing.[23]

In a survey in 1945, Er Ram had a population of 350, all Muslims,[24] and a total land area of 5,598 dunams.[25] 441 dunams were designated for plantations and irrigable land, 2,291 for cereals,[26] while 14 dunams were built-up area.[27]

Jordanian period

.jpg)

In the wake of the 1948 Arab–Israeli War, and after the 1949 Armistice Agreements, Al-Ram came under Jordanian rule.

In 1961, the population of Ram was 769.[28]

Post-1967

Since the Six-Day War in 1967, Al-Ram has been under Israeli occupation.

The population in a 1967 census conducted by the Israeli authorities was 860, 86 of whom originated from the Israeli territory.[29]

According to ARIJ, after the 1995 accords, 33.2% (or about ~2,226 dunums) of Al-Ram's land is classified as Area B land, while the remaining 66.8% (~4,482 dunums) was defined as Area C.[30] Israel has confiscated land from Al-Ram in order to build two Israeli settlement/Industrial parks:

- 315 dunums were taken for Neve Ya'akov,[31]

- 56 dunums were taken for the industrial Atarot site.[31]

In 2006, the Israeli High Court rejected three petitions objecting to the construction of a security barrier separating a-Ram from Jerusalem.[32] The route of the fence planned to encircle northern Jerusalem has been revised several times. The latest plan, effectively implemented, called for a "minimalist" route following the municipal boundary at a distance of several hundred meters. This has left the town of A-Ram almost entirely outside of the fence, with the exception of the southern part of the town, called Dahiyat al-Barid.[33][34]

Crusader remains

Two structures in the town have been identified.

Former Crusader church

The former (old) mosque of Al-Ram was once a Crusader parish church.[12][36]

In 1838, Robinson noted that "A small mosk with columns seems once to have been a church".[5]

In 1870, Guérin described "a mosque, replacing a former Christian church, of which it occupies the choir; the inhabitants venerate there the memory of Shaykh Hasen. The columns of this sanctuary come from the church."[37]

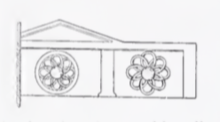

In 1881, Lieutenant Conder reported: "At the shrine which is so conspicuous near this village are remains of a former chapel. The lintel stone (as it would seem), with a bas-relief of rosettes, has been found by Dr. Chaplin within the building, and a very curious stone mask is in his possession, obtained from the village. It represents a human face without hair or beard, the nose well-cut, the eyes and mouth very feebly designed. ' The mask is hollowed out behind, and has two deep holes at the back as if to fix it to a wall. It is over a foot in longer diameter, and curiously resembles some of the faces of the Moabite collection of Mr. Shapira. There cannot well be any question of its genuine character, and nothing like it has been found, so far as I know, in Palestine.'[19][38][39]

In 1883, SWP noted that "west of the village is the Mukam of Sheik Hasein, once a small Christian basilica". It further described it as "The remains of the north aisle 6 feet 8 inches wide, are marked by four columns 2 feet in diameter. The chamber of the saint's tomb occupies part of the nave, and into its north wall the lintel of the old door is built, a stone 10 feet long, half of which is visible, with designs as shown. In the courtyard east of this chamber is an old well of good water and a fine mulberry-tree. In the west wall of the Mukam other stones, with discs in low relief, are built in."[19]

Sister cities

References

- Palmer, 1881, p. 324

- "The Separation Barrier surrounding a-Ram". Btselem. January 1, 2014. Retrieved 18 January 2014.

- "Projected Mid -Year Population for Jerusalem Governorate by Locality 2004- 2006". Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics. Archived from the original on February 7, 2012. Retrieved January 9, 2015.

- "Israel's Apartheid Wall Surrounding a-Ram". B'Tselem. Palestine Media Center. June 27, 2005. Archived from the original on September 27, 2011. Retrieved January 9, 2015.

- Robinson and Smith, 1841, vol 2, pp. 315-317

- Studium Biblicum Franciscanum, Rama - (al-Ram) Archived 2012-10-03 at the Wayback Machine, accessed 25 October 2017

- Jewish Encyclopedia, Ramah, accessed 26 October 2017

- Pringle, 1998, p. 179

- Conder and Kitchener, 1883, SWP III, p. 11

- de Roziére, 1849, p. 263: Haram, cited in Röhricht, 1893, RRH, pp. 16-17, No 74

- Röhricht, 1893, RRH, pp. 70- 71, No 278; p. 92, No 353

- Pringle, 1998, p. 180

- Röhricht, 1893, RRH, p. 96, No 365

- Hütteroth and Abdulfattah, 1977, p. 117

- Guérin, 1874, p. 199 ff

- Socin, 1879, p. 158

- Hartmann, 1883, p. 127, also noted 32 houses

- Conder and Kitchener, 1883, SWP III, p. 13

- Conder and Kitchener, 1883, SWP III, p. 155

- Schick, 1896, p. 121

- Barron, 1923, Table V||, Sub-district of Jerusalem, p. 14

- Mills, 1932, p. 42

- Pringle, 1983, p. 163

- Department of Statistics, 1945, p. 25

- Government of Palestine, Department of Statistics. Village Statistics, April, 1945. Quoted in Hadawi, 1970, p. 58 Archived 2018-11-03 at the Wayback Machine

- Government of Palestine, Department of Statistics. Village Statistics, April, 1945. Quoted in Hadawi, 1970, p. 104 Archived 2012-03-14 at the Wayback Machine

- Government of Palestine, Department of Statistics. Village Statistics, April, 1945. Quoted in Hadawi, 1970, p. 154 Archived 2014-04-27 at the Wayback Machine

- Government of Jordan, Department of Statistics, 1964, p. 23

- Perlmann, Joel (November 2011 – February 2012). "The 1967 Census of the West Bank and Gaza Strip: A Digitized Version" (PDF). Levy Economics Institute. Retrieved 24 June 2016.

- Ar Ram Town Profile, ARIJ, 2012, pp. 18-19

- Ar Ram Town Profile, ARIJ, 2012, p. 19

- High Court: A-Ram fence is our defense, Dec. 13, 2006, The Jerusalem Post

- Btselem (January 2016). "The Separation Barrier surrounding a-Ram". Retrieved 16 April 2019.

- Harel, Amos (November 10, 2003). "Separation fence to include wide area east of Jerusalem". Haaretz. Retrieved 18 January 2014.

- Pringle, 1997, p. 88

- Wilson, 1881, p. 214: picture

- Guérin, 1874, p. 200, as translated in Pringle, 1998, p. 180

- Conder, 1881, p. 196

- Conder and Kitchener, 1883, SWP III, p. 438

Bibliography

- Barron, J.B., ed. (1923). Palestine: Report and General Abstracts of the Census of 1922. Government of Palestine.

- Conder, C.R. (1881). "Lieutenant Conder´s reports". Quarterly statement - Palestine Exploration Fund. 13: 158–208.

- Conder, C.R.; Kitchener, H.H. (1883). The Survey of Western Palestine: Memoirs of the Topography, Orography, Hydrography, and Archaeology. 3. London: Committee of the Palestine Exploration Fund.

- Government of Jordan, Department of Statistics (1964). First Census of Population and Housing. Volume I: Final Tables; General Characteristics of the Population (PDF).

- Government of Palestine, Department of Statistics (1945). Village Statistics, April, 1945.

- Guérin, V. (1874). Description Géographique Historique et Archéologique de la Palestine (in French). 2: Samarie, pt. 1. Paris: L'Imprimerie Nationale.

- Hadawi, S. (1970). Village Statistics of 1945: A Classification of Land and Area ownership in Palestine. Palestine Liberation Organization Research Center. Archived from the original on 2018-12-08. Retrieved 2014-04-27.

- Hartmann, M. (1883). "Die Ortschaftenliste des Liwa Jerusalem in dem türkischen Staatskalender für Syrien auf das Jahr 1288 der Flucht (1871)". Zeitschrift des Deutschen Palästina-Vereins. 6: 102–149.

- Hütteroth, Wolf-Dieter; Abdulfattah, Kamal (1977). Historical Geography of Palestine, Transjordan and Southern Syria in the Late 16th Century. Erlanger Geographische Arbeiten, Sonderband 5. Erlangen, Germany: Vorstand der Fränkischen Geographischen Gesellschaft. ISBN 3-920405-41-2.

- Mills, E., ed. (1932). Census of Palestine 1931. Population of Villages, Towns and Administrative Areas. Jerusalem: Government of Palestine.

- Palmer, E. H. (1881). The Survey of Western Palestine: Arabic and English Name Lists Collected During the Survey by Lieutenants Conder and Kitchener, R. E. Transliterated and Explained by E.H. Palmer. Committee of the Palestine Exploration Fund.

- Pringle, D. (1983). "Two Medieval Villages North of Jerusalem: Archaeological Investigations in Al-Jib and Ar-Ram". Levant. 15: 141–177, pls.xvi-xxiia.

- Pringle, Denys (1997). Secular buildings in the Crusader Kingdom of Jerusalem: an archaeological Gazetter. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521 46010 7.

- Pringle, Denys (1998). The Churches of the Crusader Kingdom of Jerusalem: L-Z (excluding Tyre). II. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0 521 39037 0.

- Robinson, E.; Smith, E. (1841). Biblical Researches in Palestine, Mount Sinai and Arabia Petraea: A Journal of Travels in the year 1838. 2. Boston: Crocker & Brewster. ( pp. 108, 114, 141)

- Röhricht, R. (1893). (RRH) Regesta regni Hierosolymitani (MXCVII-MCCXCI) (in Latin). Berlin: Libraria Academica Wageriana. (Index: p. 491: Aram (Haram), p. 504: Rama, Ramatha )

- Röhricht, R. (1904). (RRH Ad) Regesta regni Hierosolymitani Additamentum (in Latin). Berlin: Libraria Academica Wageriana. (Index: p. 129: Aram #74; p. 134: er Ram #74; Rama #30a; (Rame? #512)

- Roziére, de, ed. (1849). Cartulaire de l'église du Saint Sépulchre de Jérusalem: publié d'après les manuscrits du Vatican (in Latin and French). Paris: Imprimerie nationale.

- Schick, C. (1896). "Zur Einwohnerzahl des Bezirks Jerusalem". Zeitschrift des Deutschen Palästina-Vereins. 19: 120–127.

- Socin, A. (1879). "Alphabetisches Verzeichniss von Ortschaften des Paschalik Jerusalem". Zeitschrift des Deutschen Palästina-Vereins. 2: 135–163.

- Toledano, E. (1984). "The Sanjaq of Jerusalem in the Sixteenth Century: Aspects of Topography and Population". Archivum Ottomanicum. 9: 279–319.

- Wilson, C.W., ed. (c. 1881). Picturesque Palestine, Sinai and Egypt. 1. New York: D. Appleton.

External links

- Welcome To al-Ram

- Al-Ramm, Welcome to Palestine

- Survey of Western Palestine, Map 17: IAA, Wikimedia commons

- Al-Ram Town (Fact Sheet), Applied Research Institute–Jerusalem (ARIJ)

- Ar Ram Town Profile, ARIJ

- Ar Ram aerial photo, ARIJ

- Locality Development Priorities and Needs in Ar Ram, ARIJ

- "Another Palestinian Ghetto in East Jerusalem: Israel Closes the Segregation Wall in Al Ram". Applied Research Institute–Jerusalem. 21 March 2005. Archived from the original on 14 August 2007.

- Oz Rosenberg (11 April 2012). "IDF closes off central Palestinian town to vehicles". Haaretz.