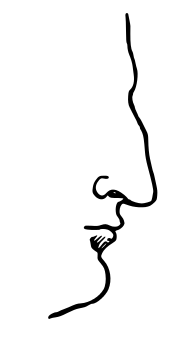

Aquiline nose

An aquiline nose (also called a Roman nose or hook nose) is a human nose with a prominent bridge, giving it the appearance of being curved or slightly bent. The word aquiline comes from the Latin word aquilinus ("eagle-like"), an allusion to the curved beak of an eagle.[1][2][3] While some have ascribed the aquiline nose to specific ethnic, racial, or geographic groups, and in some cases associated it with other supposed non-physical characteristics (e.g., intelligence, status, personality, etc., see below), no scientific studies or evidence support any such linkage. As with many other phenotypical expressions (e.g., "widow's peak", eye color, earwax type) it is found in many geographically diverse populations.

.png)

Distribution

Although the aquiline nose is found among people from nearly every area of the world, it is generally associated with and thought to be more frequent in certain ethnic groups originating from Southern Europe, the Balkans, the Caucasus, South Asia, the Middle East, North Africa, Central Asia, and the Horn of Africa. Some writers in the field of racial typology have attributed aquiline noses as a characteristic of different peoples or races; e.g.: according to anthropologist Jan Czekanowski, it is most frequently found amongst members of the Oriental race and Armenoid race. It is also often seen in the Mediterranean race and Dinarid race, where it is known as the "Roman nose" when found amongst Italians, the Southern French, Portuguese and Spanish.[4]

In racialist discourse

In racialist discourse, especially that of post-Enlightenment Western scientists and writers, a Roman nose (in an individual or a people) has been characterized as a marker of beauty and nobility,[5] but the notion itself is found early on in Plutarch, in his description of Mark Antony.[6] Among Nazi racialists the "hooked", Jewish nose was a characteristic of Jews. However, Maurice Fishberg in Jews, Race and Environment (1911) cites widely different statistics to deny that the aquiline nose (or "hook nose")[7] is characteristic of Jews, but rather to show that this type of nose occurs in all peoples of the world.[8] The supposed science of physiognomy, popular during the Victorian era, made the "prominent" nose a marker of Aryanness: "the shape of the nose and the cheeks indicated, like the forehead's angle, the subject's social status and level of intelligence. A Roman nose was superior to a snub nose in its suggestion of firmness and power, and heavy jaws revealed a latent sensuality and coarseness".[9]

Anasa (literally "those without a nose", figuratively "those without an aquiline nose") is another term frequently used in the Vedas to refer to the local, indigenous populations, whom the Aryas regarded as different from them and therefore to be stigmatized.[10]

In the modern era, critics such as Jack Shaheen in Reel Bad Arabs argues that "Hollywood's image of hook-nosed, robed Arabs parallels the image of Jews in Nazi-inspired movies ... Yesterday's Shylocks resemble today's hook-nosed sheikhs, arousing fear of the 'other'."[11]

Among Native Americans

The aquiline nose was deemed a distinctive feature of some Native American tribes, members of which often took their names after their own characteristic physical attributes (i.e. The Hook Nose, or Chief Henry Roman Nose).[4] In the depiction of Native Americans, for instance, an aquiline nose is one of the standard traits of the "noble warrior" type.[12] It is so important as a cultural marker, Renee Ann Cramer argued in Cash, Color, and Colonialism (2005), that tribes without such characteristics have found it difficult to receive "federal recognition" or "acknowledgement" from the US government, which is necessary to have a continuous government-to-government relationship with the United States.[13]

Among populations in North Africa

The flat, broad nose is ubiquitous among most populations in Sub-Saharan Africa,[14] and is noted by nineteenth-century writers and travelers (such as Colin Mackenzie) as a mark of "Negroid" ancestry.[15] It stands in opposition to the narrow aquiline, straight or convex noses (lepthorrine), which are instead deemed "Caucasian".[14]

In the 1930s, an aquiline nose was reported to be regarded as a characteristic of beauty for girls among the Tswana and Xhosa people. However, a recent scholar could not discern from the original study "whether such preferences were rooted in precolonial conceptions of beauty, a product of colonial racial hierarchies, or some entanglement of the two".[16] A well-known example of the aquiline nose as a marker in Africa contrasting the bearer with his/her contemporaries is the protagonist of Aphra Behn's Oroonoko (1688). Although an African prince, he speaks French, has straightened hair, thin lips, and a "nose that was rising and Roman instead of African and flat".[17] These features set him apart from most of his peers, and marked him instead as noble and on par with Europeans.[18][19][20]

According to craniometric analysis by Carleton Coon (1939), aquiline noses in Africa are largely restricted to populations from North Africa and the Horn of Africa (in contrast to those of Sub-Saharan Africa), which is more generally peopled by those of Semitic, Arab, and other non-"Negroid" descent. However, they are generally less common in these areas than are narrow, straight noses, which instead constitute the majority of nasal profiles. It has been reported however, that aquiline noses are more prevalent among Algerian, Egyptian, Tunisian, Moroccan, Eritrean, Ethiopian and Somali people, than among Southern Europeans.[21][22] Among the Copts and Fellahin of Egypt, three nasal types reportedly exist: one with a narrow, aquiline nose accompanied by a slim face, slender jaw and thin lips; secondly a slightly lower rooted, straight-to-concave nose, accompanied by a wider and lower face, a strong jaw, prominent chin, moderately wide; thirdly a wide nose on either including those with high and low cheekbones.[23]

Among Nordic peoples

For Western racial anthropologists such as Madison Grant (in The Passing of the Great Race (1911) and other works) and William Z. Ripley, the aquiline nose is characteristic of the peoples they variously identify Nordic, Teutonic, Celtic, Norman, Frankish, and Anglo-Saxon.[24] Grant, after defining the Nordics as having aquiline noses, went back through history and found such a nose and other characteristics he called "Nordic" in many historically prominent men. Among these were Dante Alighieri, "all the chief men of the Renaissance", as well as King David. Grant identified Jesus Christ as having had those "physical and moral attributes" (emphasis added).[25]

Among South Asian peoples

A prominent aquiline (or high-bridged) nose is seen as a feature of powerful or heroic figures in traditional Hindu mythology, as well as a beauty standard in ancient Indian and Southeast Asian societies.[26] Among specific ethnic groups, the aquiline nose type is most common among the peoples of Afghanistan, Dardistan, Pakistan and Kashmir[27], as well as a prominent feature in the Greco-Buddhist statuary of Gandhara (a region spanning the upper Indus and Kabul river valleys throughout northern Pakistan and Kashmir).[28] The ethnographer George Campbell, in his Ethnology of India, states that:

"The high nose, slightly aquiline, is a common type [among Kashmiri Brahmins]. Raise a little the brow of a Greek statue and give the nose a small turn at the bony point in front of the bridge, so as to break the straightness of the line, you have the model type of this part of India, to be found both in living men and in the statues of the Peshawar Valley."[29]

The traveller (and personal physician at the Mughal court) Francois Bernier, one of the first Europeans to visit Kashmir, posited that Kashmiris were descended from Jews on account of their prominent noses and fair skin.[30]

See also

- Anatomy of the human nose

- Jewish nose

References

- Cook, Eliza (1851). Eliza Cook's Journal. J. O. Clark. p. 381.

- Fredriksen, John C. (1 January 2001). America's Military Adversaries: From Colonial Times to the Present. ABC-CLIO. p. 432. ISBN 978-1-57607-603-3.

He matured into a powerfully built man, tall, muscular, with an aquiline profile that gave rise to the name Woquni, or “Hook Nose.” The whites translated this into the more familiar moniker of Roman Nose. In his early youth, Roman Nose ...

- Neuman, Henry; Baretti, Giuseppe Marco Antonio (1827). Neuman and Baretti's Dictionary of the Spanish and English Languages: Spanish and English. Hilliard, Gray, Little, and Wilkins. p. 65.

Aquiline, resembling an eagle; when applied to the nose, hooked.

- Czekanowski, Jan (1934). Człowiek w Czasie i Przestrzeni (eng. A Human in Time and Space) - The lexicon of biological anthropology. Kraków, Poland: Trzaska, Ewert i Michalski - Bibljoteka Wiedzy.

- Adams, Mikaëla M. (2009). "Savage Foes, Noble Warriors, and Frail Remnants: Florida Seminoles in the White Imagination, 1865-1934". The Florida Historical Quarterly. 87 (3): 404–35. JSTOR 20700234.

- Jones, Prudence J. (2006). Cleopatra: A Sourcebook. U of Oklahoma P. p. 94. ISBN 9780806137414.

- "Hooknose". Merriam-Webster. Retrieved 19 September 2014.

- Fishberg, Maurice. Jews, Race and Environment. Transaction. p. 83. ISBN 9781412826952.

- Cowling, Mary (1989). The Artist as Anthropologist: The Representation of Type and Character in Victorian Art. Cambridge. Cambridge UP. Quoted in McNees, Eleanor (2004). "Punch and the Pope: Three Decades of Anti-Catholic Caricature". Victorian Periodicals Review. 37 (1): 18–45. JSTOR 20083988.

- Excerpt From: B.R. Ambedkar, Arundhati Roy, S. Anand. “Annihilation of Caste”.

- Shaheen, Jack G. (July 2003). "Reel Bad Arabs: How Hollywood Vilifies a People". The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science. 588 (1): 173. doi:10.1177/0002716203588001011. ISSN 0002-7162.

- Cramer, Renee Ann (2006). "The Common Sense of Anti-Indian Racism: Reactions to Mashantucket Pequot Success in Gaming and Acknowledgment". Law & Social Inquiry. 31 (2): 313–41. doi:10.1111/j.1747-4469.2006.00013.x. JSTOR 4092749.

- McCulloch, Anne M. (2006). "Rev. of Cramer, Cash, Color, and Colonialism". Perspectives on Politics. 4 (1): 178–79. doi:10.1017/s1537592706430140. JSTOR 3688655.

- Heidari Z, Mahmoudzadeh-Sagheb H, Khammar T, Khammar M (May 2009). "Anthropometric measurements of the external nose in 18–25-year-old Sistani and Baluch aborigine women in the southeast of Iran". Folia Morphol. (Warsz). 68 (2): 88–92. PMID 19449295.

- Sundberg, Jeffrey Roger (2006). "Considerations on the dating of the Barabuḍur stūpa". Bijdragen tot de Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde. 162 (1): 95–132. doi:10.1163/22134379-90003675. JSTOR 27868287.

- Thomas, Lynn M. (2006). "The Modern Girl and Racial Respectability in 1930s South Africa". The Journal of African History. 47 (3): 461–90. doi:10.1017/s0021853706002131. JSTOR 4501073.

- Behn, Aphra (1987). Adelaide P. Amore (ed.). Oroonoko, Or, The Royal Slave: A Critical Edition. UP of America. p. 10. ISBN 9780819165299.

- Gates, Henry Louis (1998). "Introduction". In Henry Louis Gates; William L. Andrews (eds.). Pioneers of the Black Atlantic: Five Slave Narratives from the Enlightenment, 1772-1815. Civitas. pp. 1–30. ISBN 9781887178983.

- Popkin, Richard Henry (1988). Millenarianism and Messianism in English Literature and Thought, 1650-1800: Clark Library Lectures, 1981-1982. Brill. p. 206. ISBN 9789004085138.

- Bohls, Elizabeth (2013). Romantic Literature and Postcolonial Studies. Oxford UP. p. 52. ISBN 9780748678754.

- Coon, Carleton (1939). The Races of Europe. The Macmillan Company. p. Chapter XI, Section 13 – Eastern Barbary, Algeria and Tunisia. Retrieved 7 June 2014.

- Coon, Carleton (1939). The Races of Europe. The Macmillan Company. p. Chapter XI, Section 8 – The Mediterranean Race in East Africa. Retrieved 7 June 2014.

- Coon, Carleton (1939). The Races of Europe. The Macmillan Company. p. Chapter XI, Section 9 – The Modern Egyptians. Retrieved 7 June 2014.

- Winlow, Heather (2006). "Mapping Moral Geographies: W. Z. Ripley's Races of Europe and the United States". Annals of the Association of American Geographers. 96 (1): 119–41. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8306.2006.00502.x. JSTOR 3694148.

- Spiro, Jonathan (2009). Defending the Master Race: Conservation, Eugenics, and the Legacy of Madison Grant. UPNE. pp. 147–51. ISBN 9781584658108.

- Meyer, Johann Jakob (1971). Sexual Life in Ancient India: A Study in the Comparative History of Indian Culture. Motilal Banarsidass Publ. ISBN 9788120806382.

- Man in India. A. K. Bose. 1940.

- Bamzai, P. N. K. (1994). Culture and Political History of Kashmir. M.D. Publications Pvt. Ltd. ISBN 9788185880310.

- Kaw, M. K. (2001). Kashmiri Pandits: Looking to the Future. APH Publishing. ISBN 9788176482363.

- Stuurman, Siep (2000). "François Bernier and the Invention of Racial Classification". History Workshop Journal. 50 (50): 1–21. doi:10.1093/hwj/2000.50.1. ISSN 1363-3554. JSTOR 4289688. PMID 11624673.

Suggested reading

- Barolsky, Paul (2007). Michelangelo's Nose: A Myth and Its Maker. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 9780271032726.