April Fools' Day

April Fools' Day or April Fool's Day is an annual custom on April 1 consisting of practical jokes and hoaxes. Jokesters often expose their actions by shouting "April Fools!" at the recipient. Mass media can be involved in these pranks, which may be revealed as such the following day. The day is not a public holiday in any country except Odessa in Ukraine, where the first of April is an official city holiday.[1] The custom of setting aside a day for playing harmless pranks upon one's neighbor has been relatively common in the world historically.[2]

| April Fools | |

|---|---|

An April Fools' Day prank marking the construction of the Copenhagen Metro in 2001 | |

| Also called | All Fools' Day |

| Type | Cultural, Western |

| Significance | Practical jokes, pranks |

| Observances | Comedy |

| Date | April 1 |

| Next time | 1 April 2021 |

| Frequency | Annual |

Origins

A disputed association between April 1 and foolishness is in Geoffrey Chaucer's The Canterbury Tales (1392).[3] In the "Nun's Priest's Tale", a vain cock Chauntecleer is tricked by a fox on Syn March bigan thritty dayes and two.[4] Readers apparently understood this line to mean "32 March", i.e. April 1.[5] However, it is not clear that Chaucer was referencing April 1, since the text of the "Nun's Priest's Tale" also states that the story takes place on the day when the sun is in the signe of Taurus had y-runne Twenty degrees and one, which cannot be April 1. Modern scholars believe that there is a copying error in the extant manuscripts and that Chaucer actually wrote, Syn March was gon.[6] If so, the passage would have originally meant 32 days after March, i.e. 2 May,[7] the anniversary of the engagement of King Richard II of England to Anne of Bohemia, which took place in 1381.

In 1508, French poet Eloy d'Amerval referred to a poisson d'avril (April fool, literally "fish of April"), possibly the first reference to the celebration in France.[8] Some writers suggest that April Fools' originated because in the Middle Ages, New Year's Day was celebrated on March 25 in most European towns,[9] with a holiday that in some areas of France, specifically, ended on April 1,[10][11] and those who celebrated New Year's Eve on January 1 made fun of those who celebrated on other dates by the invention of April Fools' Day.[10] The use of January 1 as New Year's Day became common in France only in the mid-16th century,[7] and the date was not adopted officially until 1564, by the Edict of Roussillon.

In 1561, Flemish poet Eduard de Dene wrote of a nobleman who sent his servants on foolish errands on April 1.[7]

In the Netherlands, the origin of April Fools' Day is often attributed to the Dutch victory in 1572 at Brielle, where the Spanish Duke Álvarez de Toledo was defeated. Op 1 april verloor Alva zijn bril is a Dutch proverb, which can be translated as: "On the first of April, Alva lost his glasses." In this case, "bril" ("glasses" in Dutch) serves as a homonym for Brielle. This theory, however, provides no explanation for the international celebration of April Fools' Day.

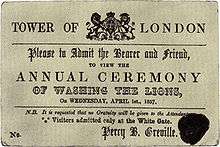

In 1686, John Aubrey referred to the celebration as "Fooles holy day", the first British reference.[7] On April 1, 1698, several people were tricked into going to the Tower of London to "see the Lions washed".[7]

Although no Biblical scholar or historian is known to have mentioned a relationship, some have expressed the belief that the origins of April Fool's Day may go back to the Genesis flood narrative. In a 1908 edition of the Harper's Weekly cartoonist Bertha R. McDonald wrote:

Authorities gravely back with it to the time of Noah and the ark. The London Public Advertiser of March 13, 1769, printed: "The mistake of Noah sending the dove out of the ark before the water had abated, on the first day of April, and to perpetuate the memory of this deliverance it was thought proper, whoever forgot so remarkable a circumstance, to punish them by sending them upon some sleeveless errand similar to that ineffectual message upon which the bird was sent by the patriarch".[2]

Long-standing customs

United Kingdom

In the UK, an April Fool prank is sometimes later revealed by shouting "April fools!" at the recipient, who becomes the "April fool". A study in the 1950s, by folklorists Iona and Peter Opie, found that in the UK, and in countries whose traditions derived from the UK, the joking ceased at midday.[12] This continues to be the current practice, with the custom ceasing at noon, after which time it is no longer acceptable to play pranks.[13] Thus a person playing a prank after midday is considered the "April fool" themselves.[14]

In Scotland, April Fools' Day was traditionally called 'Huntigowk Day',[12] although this name has fallen into disuse. The name is a corruption of 'Hunt the Gowk', "gowk" being Scots for a cuckoo or a foolish person; alternative terms in Gaelic would be Là na Gocaireachd, 'gowking day', or Là Ruith na Cuthaige, 'the day of running the cuckoo'. The traditional prank is to ask someone to deliver a sealed message that supposedly requests help of some sort. In fact, the message reads "Dinna laugh, dinna smile. Hunt the gowk another mile." The recipient, upon reading it, will explain he can only help if he first contacts another person, and sends the victim to this next person with an identical message, with the same result.[12]

In England a "fool" is known by different names around the country, including a "noodle", "gob", "gobby" or "noddy".[15]

Ireland

In Ireland, it was traditional to entrust the victim with an "important letter" to be given to a named person. That person would read the letter, then ask the victim to take it to someone else, and so on. The letter when opened contained the words "send the fool further".[16]

Prima aprilis in Poland

In Poland, prima aprilis ("1 April" in Latin) as a day of pranks is a centuries-long tradition. It is a day when many pranks are played: hoaxes – sometimes very sophisticated – are prepared by people, media (which often cooperate to make the "information" more credible) and even public institutions. Serious activities are usually avoided, and generally every word said on April 1 can be untrue. The conviction for this is so strong that the Polish anti-Turkish alliance with Leopold I signed on April 1, 1683, was backdated to March 31.[17] However, for some in Poland prima aprilis ends at noon of April 1, and prima aprilis jokes after that hour are considered inappropriate and not classy.

Nordic countries

Danes, Finns, Icelanders, Norwegians and Swedes celebrate April Fools' Day (aprilsnar in Danish; aprillipäivä in Finnish; aprilskämt in Swedish). Most news media outlets will publish exactly one false story on April 1; for newspapers this will typically be a first-page article but not the top headline.[18]

April fish

In Italy, France, Belgium and French-speaking areas of Switzerland and Canada, April 1 tradition is often known as "April fish" (poisson d'avril in French, april vis in Dutch or pesce d'aprile in Italian). This includes attempting to attach a paper fish to the victim's back without being noticed. Such fish feature is prominently present on many late 19th- to early 20th-century French April Fools' Day postcards. Many newspapers also spread a false story on April Fish Day, and a subtle reference to a fish is sometimes given as a clue to the fact that it is an April Fools' prank.

Ukraine

April Fools' Day is widely celebrated in Odessa and has special local name Humorina. For the first time this holiday arose in 1973.[19] April Fool prank is revealed by saying "Первое Апреля, никому не верю" (which means "April First, trust nobody") at the recipient. The festival includes a large parade in the city center, free concerts, street fairs and performances. Festival participants dress up in a variety of costumes and walk around the city fooling around and pranks with passersby. One of the traditions on fool's day is to dress up the main city monument in funny clothes. Humorina even has its own logo — a cheerful sailor in life ring — whose author was an artist, Arkady Tsykun.[20] During the festival, special souvenirs with a logo are printed and sold everywhere. Since 2010, April Fools' Day celebrations include an International Clown Festival and both celebrated as one. In 2019, the festival was dedicated to the 100th anniversary of the Odessa Film Studio and all events were held with an emphasis on cinema.[21]

Lebanon

In Lebanon, an April Fool prank is revealed by saying "كذبة أول نيسان " (which means "April First Lie") at the recipient.

Spanish-speaking countries

In many Spanish-speaking countries (and the Philippines), "Dia de los Santos Inocentes" (Holy Innocents Day) is a festivity which is very similar to the April Fools' Day, but it is celebrated in late December (27, 28 or 29 depending on the location, or January 10th for East Syrians).

Israel

As a Western country, Israel has adopted the custom of pranking on April Fools' Day.[22]

Pranks

As well as people playing pranks on one another on April Fools' Day, elaborate pranks have appeared on radio and TV stations, newspapers, and websites, and have been performed by large corporations. In one famous prank in 1957, the BBC broadcast a film in their Panorama current affairs series purporting to show Swiss farmers picking freshly-grown spaghetti, in what they called the Swiss Spaghetti Harvest. The BBC were soon flooded with requests to purchase a spaghetti plant, forcing them to declare the film a hoax on the news the next day.[23]

With the advent of the Internet and readily available global news services, April Fools' pranks can catch and embarrass a wider audience than ever before.[24]

Comparable prank days

December 28

December 28, the equivalent day in Spain, Hispanic America and the Philippines, is also the Christian day of celebration of the "Day of the Holy Innocents.” The Christian celebration is a religious holiday in its own right, but the tradition of pranks is not, though the latter is observed yearly. In some regions of Hispanic America after a prank is played, the cry is made, "Inocente palomita que te dejaste engañar" ("You innocent little dove that let yourself be fooled!"; not to be confused with another meaning of palomita, which means “popcorn” in some dialects).

In Mexico, the phrase is, “¡Inocente palomita que te dejaste engañar!” which means "Innocent pigeon you let yourself be fooled!".

In Argentina, the prankster's says, “¡Que la inocencia te valga!” which roughly translates as advice to not be as gullible as the victim of the prank. In Spain, it is common to say just “¡Inocente!” (which in Spanish can mean "innocent” or "gullible").[25]

In Colombia, the term is used as "Pásala por Inocentes", which roughly means: "Let it go; today it's Innocent's Day."

In Belgium, this day is also known as the "Day of the innocent children" or "Day of the stupid children". It used to be a day where parents, grandparents, and teachers would fool the children in some way. But the celebration of this day has died out in favor of April Fools' Day.

Nevertheless, on the Spanish island of Menorca, Dia d'enganyar ("Fooling day") is celebrated on April 1 because Menorca was a British possession during part of the 18th century. In Brazil, the "Dia da mentira" ("Day of the lie") is also celebrated on April 1.[25]

First day of a new month

In many English-speaking countries, mainly Britain, Ireland, Australia, New Zealand and South Africa, it is a custom to say "pinch and a punch for the first of the month" or an alternative, typically by children. The victim might respond with "a flick and a kick for being so quick", and the attacker might reply with "a punch in the eye for being so sly".[26]

Reception

The practice of April Fool pranks and hoaxes is controversial.[14][27] The mixed opinions of critics are epitomized in the reception to the 1957 BBC "Spaghetti-tree hoax", in reference to which, newspapers were split over whether it was "a great joke or a terrible hoax on the public".[28]

The positive view is that April Fools' can be good for one's health because it encourages "jokes, hoaxes...pranks, [and] belly laughs", and brings all the benefits of laughter including stress relief and reducing strain on the heart.[29] There are many "best of" April Fools' Day lists that are compiled in order to showcase the best examples of how the day is celebrated.[30] Various April Fools' campaigns have been praised for their innovation, creativity, writing, and general effort.[31]

The negative view describes April Fools' hoaxes as "creepy and manipulative", "rude" and "a little bit nasty", as well as based on schadenfreude and deceit.[27] When genuine news or a genuine important order or warning is issued on April Fools' Day, there is risk that it will be misinterpreted as a joke and ignored – for example, when Google, known to play elaborate April Fools' Day hoaxes, announced the launch of Gmail with 1-gigabyte inboxes in 2004, an era when competing webmail services offered 4-megabytes or less, many dismissed it as a joke outright.[32][33] On the other hand, sometimes stories intended as jokes are taken seriously. Either way, there can be adverse effects, such as confusion,[34] misinformation, waste of resources (especially when the hoax concerns people in danger) and even legal or commercial consequences.[35][36]

People obeying hoax messages to telephone "Mr C. Lion" or "Mr L. E. Fant" and suchlike on a telephone number that turns out to be a zoo, sometimes cause a serious overload to zoos' telephone switchboards.

Other examples of genuine news on April 1 mistaken as a hoax include:

- 1 April 1946: Warnings about the Aleutian Island earthquake's tsunami that killed 165 people in Hawaii and Alaska.

- 1 April 2005: News that the comedian Mitch Hedberg had died on 29 March 2005.

- 1 April 2005: Announcement about Powerpuff Girls Z, by Aniplex, Cartoon Network and Toei Animation.[37]

- 1 April 2009: Announcement that the long running soap opera Guiding Light was being cancelled.

In popular culture

Books, films, telemovies and television episodes have used April Fool's Day as their title or inspiration. Examples include Bryce Courtenay's novel April Fool's Day (1993), whose title refers to the day Courtenay's son died. The 1990s sitcom Roseanne featured an episode titled "April Fools' Day". This turned out to be intentionally misleading, as the episode was about Tax Day in the United States on April 15 – the last day to submit the previous year's tax information.

References

- "1 апреля будет в Одессе выходным днем" [1 April becomes a holiday in Odessa]. ФАКТЫ (in Russian). March 23, 2003.

- McDonald, Bertha R. (March 7, 1908). "The Oldest Custom in the World". Harper's Weekly. 52 (2672). p. 26.

- Ashley Ross (March 31, 2016). "No Kidding: We Have No Idea How April Fools' Day Started". Time Magazine. Retrieved March 24, 2018.

- The Canterbury Tales, "The Nun's Priest's Tale" - "Chaucer in the Twenty-First Century", University of Maine at Machias, September 21, 2007

- Compare to Valentine's Day, a holiday that originated with a similar misunderstanding of Chaucer.

- Travis, Peter W. (1997). "Chaucer's Chronographiae, the Confounded Reader, and Fourteenth-Century Measurements of Time". In Poster, Carol; Utz, Richard J. (eds.). Constructions of Time in the Late Middle Ages. Evanston IL: Northwestern University Press. pp. 16–17. ISBN 0-8101-1541-7.

- Boese, Alex (2008). "The Origin of April Fool's Day". Museum of Hoaxes.

- Eloy d'Amerval, Le Livre de la Deablerie, Librairie Droz, p. 70. (1991). "De maint homme et de mainte fame, poisson d'Apvril vien tost a moy."

- Groves, Marsha, Manners and Customs in the Middle Ages, p. 27 (2005).

- "April Fools' Day". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved April 4, 2013.

- Santino, Jack (1972). All around the year: holidays and celebrations in American life. University of Illinois Press. p. 97. ISBN 978-0-252-06516-3.

- Opie, Iona & Peter (1960). The Lore and Language of Schoolchildren. Oxford University Press. pp. 245–46. ISBN 0-940322-69-2.

- Office, Great Britain: Home (2017). Life in the United Kingdom: a guide for new residents (2014 ed.). Stationery Office. ISBN 9780113413409.

- Archie Bland (April 1, 2009). "The Big Question: How did the April Fool's Day tradition begin, and what are the best tricks?". The Independent. Retrieved April 4, 2013.

- "Different names in Different parts of England". April Fool's Day. April 1, 2016. Retrieved March 12, 2016.

- Haggerty, Bridget. "April Fool's Day". Irish Culture and Customs. Retrieved April 3, 2014.

- "Origin of April Fools' Day". The Express Tribune. Retrieved May 27, 2013.

- "April Fool's Day: 8 Interesting Things And Hoaxes You Didn't Know". International Business Times. Retrieved May 27, 2013.

- Sinelnikova, Alexandra (April 1, 2019). "Humorina time". Odessitclub.

- "Main festival in Odessa". 2019.

- "Odessa celebrates Humorine. Picture story". April 1, 2019.

- Adam, Soclof (March 31, 2011). "From the JTA Archive: April Fools' Day lessons for Jewish pranksters". Jewish Telegraph Agency. JTA. Retrieved April 3, 2019.

- "Swiss Spaghetti Harvest". Retrieved November 1, 2013.

- Moran, Rob (April 4, 2014). "NPR's Brilliant April Fools' Day Prank Was Sadly Lost On Much Of The Internet". Retrieved April 6, 2014.

- "Avui és el Dia d'Enganyar a Menorca" [Today is Fooling Day on Minorca] (in Catalan). Vilaweb. April 1, 2003. Retrieved April 4, 2013.

- "pinch and a punch for the first of the month - Wiktionary". en.wiktionary.org. Retrieved May 11, 2020.

- Doll, Jen (April 1, 2013). "Is April Fools' Day the Worst Holiday? – Yahoo News". Yahoo! News. Retrieved April 1, 2014.

- "Is this the best April Fool's ever?". BBC. Retrieved April 1, 2014.

- "Why April Fools' Day is Good For Your Health – Health News and Views". News.Health.com. April 1, 2013. Retrieved April 1, 2014.

- "April Fools: the best online pranks | SBS News". Sbs.com.au. Retrieved April 1, 2014.

- "April Fool's Day: A Global Practice". aljazirahnews. April 1, 2019. Retrieved April 8, 2019.

- Harry McCracken (April 1, 2013). "Google's Greatest April Fools' Hoax Ever (Hint: It Wasn't a Hoax)". TIME.com. Retrieved August 1, 2014.

- Lisa Baertlein (April 1, 2004). "Google: 'Gmail' no joke, but lunar jobs are". Reuters. Retrieved August 1, 2014.

- Woods, Michael (April 2, 2013). "Brazeau tweets his resignation on April Fool's Day, causing confusion – National". Globalnews.ca. Retrieved April 1, 2014.

- Hasham, Nicole (April 3, 2013). "ASIC to look into prank Metgasco email from schoolgirl Kudra Falla-Ricketts". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved April 3, 2014.

- "Justin Bieber's Believe album hijacked by DJ Paz". The Sydney Morning Herald. April 3, 2014. Retrieved April 3, 2014.

- "Powerpuff Girls Z Debut".

Further reading

- Wainwright, Martin (2007). The Guardian Book of April Fool's Day. Aurum. ISBN 1-84513-155-X

- Dundes, Alan (1988). "April Fool and April Fish: Towards a Theory of Ritual Pranks". Etnofoor. 1 (1): 4–14. JSTOR 25757645.

External links

| Wikinews has related news: |

| Wikisource has the text of the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article April-Fools' Day. |

- "Top 100 April Fools' Day hoaxes of all time". Museum of Hoaxes.

- "April Fools' Day On The Web: List of all known April Fools' Day Jokes websites from 2004 until present".

| Library resources about April Fools' Day |