Uniform Crime Reports

The Uniform Crime Reporting (UCR) program compiles official data on crime in the United States, published by the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI). UCR is "a nationwide, cooperative statistical effort of nearly 18,000 city, university and college, county, state, tribal, and federal law enforcement agencies voluntarily reporting data on crimes brought to their attention".[1]

| Uniform Crime Reporting | |

|---|---|

| Active | 1930 - Present |

| Country | United States |

| Agency | Federal Bureau of Investigation |

| Type | Crime statistics program |

| Role | Collection and publishing |

| Part of | Criminal Justice Information Services Division |

| Abbreviation | UCR |

| Website | |

| Official website | |

Crime statistics are compiled from UCR data and published annually by the FBI in the Crime in the United States series.

The FBI does not collect the data itself. Rather, law enforcement agencies across the United States provide the data to the FBI, which then compiles the Reports.

The Uniform Crime Reporting program began in 1929, and since then has become an important source of crime information for law enforcement, policymakers, scholars, and the media. The UCR Program consists of four parts:

- Traditional Summary Reporting System (SRS) and the National Incident-Based Reporting System (NIBRS) – Offense and arrest data

- Law Enforcement Officers Killed and Assaulted (LEOKA) Program

- Hate Crime Statistics Program – hate crimes

- Cargo Theft Reporting Program – cargo theft

The FBI publishes annual data from these collections in Crime in the United States, Law Enforcement Officers Killed and Assaulted, and Hate Crime Statistics.

History

The UCR Program was based upon work by the International Association of Chiefs of Police (IACP) and the Social Science Research Council (SSRC)[2] throughout the 1920s to create a uniform national set of crime statistics, reliable for analysis. In 1927, the IACP created the Committee on Uniform Crime Reporting to determine statistics for national comparisons. The committee determined seven crimes fundamental to comparing crime rates: murder and non-negligent manslaughter, forcible rape, burglary, aggravated assault, larceny and motor vehicle theft (the eighth, arson, was added under a congressional directive in 1979). The early program was managed by the IACP, prior to FBI involvement, done through a monthly report. The first report in January 1930 reported data from 400 cities throughout 43 states, covering more than 20 million individuals, approximately twenty percent of the total U.S. population.[3]

On June 11, 1930, through IACP lobbying, the United States Congress passed legislation enacting 28 U.S.C. § 534, which granted the office of the Attorney General the ability to "acquire, collect, classify, and preserve identification, criminal identification, crime, and other records" with the ability to appoint officials to oversee this duty, including the subordinate members of the Bureau of Investigation. The Attorney General, in turn, designated the FBI to serve as the national clearinghouse for the data collected, and the FBI assumed responsibility for managing the UCR Program in September 1930. The July 1930 issue of the IACP crime report announced the FBI's takeover of the program. While the IACP discontinued oversight of the program, they continued to advise the FBI to better the UCR.

Since 1935, the FBI served as a data clearinghouse; organizing, collecting, and disseminating information voluntarily submitted by local, state, federal and tribal law enforcement agencies. The UCR remained the primary tool for collection and analysis of data for the next half century. Throughout the 1980s, a series of National UCR Conferences were with members from the IACP, Department of Justice, including the FBI, and newly formed Bureau of Justice Statistics (BJS). The purpose was to determine necessary system revisions and then implement them. The result of these conferences was the release of a Blueprint for the Future of the Uniform Crime Reporting Program release in May 1985, detailing the necessary revisions. The report proposed splitting reported data into two separate categories, the eight serious crimes (which later became known as "Part I index crimes") and 21 less commonly reported crimes (which later became known as "Part II index crimes").

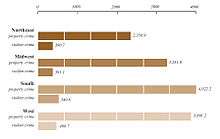

In 2003, FBI UCR data were compiled from more than 16,000 agencies, representing 93 percent of the population[4] in 46 states and the District of Columbia.[5] While nationally reporting is not mandated, many states have instituted laws requiring law enforcement within those states to provide UCR data.

Data collection

Each month, law enforcement agencies report the number of known index crimes in their jurisdiction to the FBI. This mainly includes crimes reported to the police by the general public, but may also include crimes that police officers discover, and known through other sources. Law enforcement agencies also report the number of crime cases cleared.

UCR crime categories

For reporting purposes, criminal offenses are divided into two major groups: Part I offenses and Part II offenses.

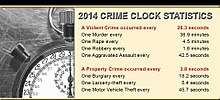

In Part I, the UCR indexes reported incidents of index crimes which are broken into two categories: violent and property crimes. Aggravated assault, forcible rape, murder, and robbery are classified as violent while arson, burglary, larceny-theft, and motor vehicle theft are classified as property crimes. These are reported via the document named Return A – Monthly Return of Offenses Known to the Police. Part 1 crimes are collectively known as Index crimes, this name is used because the crimes are considered quite serious, tend to be reported more reliably than others, and the reports are taken directly by the police and not a separate agency which aggregates the data and does not necessarily contribute to the UCR.

In Part II, the following categories are tracked: simple assault, curfew offenses and loitering, embezzlement, forgery and counterfeiting, disorderly conduct, driving under the influence, drug offenses, fraud, gambling, liquor offenses, offenses against the family, prostitution, public drunkenness, runaways, sex offenses, stolen property, vandalism, vagrancy, and weapons offenses.

Two property reports are also included in addition to the "Return A". The first is the Property Stolen by Classification report. This report details the number of actual crimes of each type in the "Return A" and the monetary value of property stolen in conjunction with that crime. Some offenses are reported in greater detail on this report than on the "Return A". For example, on the "Report A", burglaries are divided into three categories: Forcible Entry, Unlawful Entry – No Force, and Attempted Forcible Entry. On the Property Stolen by Classification report, burglaries are divided into six categories based on location, type (method and success of entry), and the time of the offense. Offenses are counted in residences with offense times of 6 p.m. to 6 a.m., 6 a.m. to 6 p.m. and Unknown Time and Non-residences with the same three time groupings.

The second property report is the Property Stolen by Type (of Property) and Value report. The monetary value of both stolen and recovered property are totaled and classified as one of eleven property types:

- Currency, Notes, Etc.

- Jewelry and Precious Metals

- Clothing and Furs

- Locally Stolen Motor Vehicles

- Office Equipment

- Televisions, Radios, Stereos, Etc.

- Firearms

- Household goods

- Consumable goods

- Livestock

- Miscellaneous

The FBI began recording arson rates, as part of the UCR, in 1979. This report details arsons of the following property types:

- Single Occupancy Residential (houses, townhouses, duplexes, etc.)

- Other Residential (apartments, tenements, flats, hotels, motels, dormitories, etc.)

- Storage (barns, garages, warehouses, etc.)

- Industrial/Manufacturing

- Other Commercial (stores, restaurants, offices, etc.)

- Community/Public (churches, jails, schools, colleges, hospitals, etc.)

- All Other Structures (out buildings, monuments, buildings under construction, etc.)

- Motor Vehicles (automobiles, trucks, buses, motorcycles, etc.)

- Other Mobile Property (trailers, recreational vehicles, airplanes, boats, etc.)

- Other (crops, timber, fences, signs, etc.)

Advisory groups

The Criminal Justice Information Systems Committees of the International Association of Chiefs of Police (IACP) and the National Sheriffs' Association (NSA) serve in an advisory capacity to the UCR Program and encourage local police departments and sheriff's departments to participate fully in the program.

In 1988, a Data Providers' Advisory Policy Board was established to provide input for UCR matters. The Board operated until 1993 when it combined with the National Crime Information Center Advisory Policy Board to form a single Advisory Policy Board (APB) to address all issues regarding the FBI's criminal justice information services. In addition, the Association of State UCR Programs (ASUCRP) focuses on UCR issues within individual state law enforcement associations and promotes interest in the UCR Program. These organizations foster widespread and responsible use of UCR statistics and assist data contributors when needed.

Limitations

The UCR itself warns that it reflects crime reports by police, not later adjudication.

References

- "Summary of the Uniform Crime Reporting Program". fbi.gov. 1987-09-30. Retrieved 2012-12-30.

- Lawrence Rosen, "The Creation of the Uniform Crime Report", Social Science History 19:2 (Summer 1995):215–238.

- Crime in the United States 2000. (PDF). Federal Bureau of Investigation, U.S. Department of Justice. Washington, D.C.. Retrieved on 30 March 2008. Archived on 14 April 2010.

- Frequently Asked Questions. Federal Bureau of Investigation, U.S. Department of Justice. Washington, D.C.. Uniform Crime Reports. Retrieved on 2008-03-30.

- UCR and NIBRS Participation Archived 2006-04-25 at the Wayback Machine. U.S. Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics. Washington, D.C. Retrieved on 2008-03-30.

Further reading

- Lynch, J. P., & Addington, L. A. (2007). Understanding crime statistics: revisiting the divergence of the NCVS and UCR. Cambridge studies in criminology. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521862042