Anatolie Popa

Anatolie Popa (Russian: Анатолий Васильевич Попа, Anatoliy Vasilievich Popa; March 15, 1896 – June 25, 1920) was a Bessarabian-born military commander active during World War I and the Russian Revolution and Civil War, one of the organisers of the Moldavian armed resistance against the advancing Romanian troops in January 1918.

Anatolie Popa | |

|---|---|

.jpg) | |

| Born | March 15, 1896 Cotiujenii Mari, Soroksky Uyezd, Bessarabia Governorate, Russian Empire |

| Died | June 25, 1920 (aged 24) Novo-Miropol', Ukraine |

| Allegiance | Russian Empire Moldavian Democratic Republic Soviet Russia |

| Service/ | Imperial Russian Army Bessarabian Army Red Army |

| Years of service | 1914–1917 1917–1918 1918–1920 |

| Rank | Stabs-kapitan Military commissar Regimental Commander |

| Unit | 75th Sevastopol Infantry Regiment Bălți County Moldavian Cohorts 45th Rifle Division |

| Battles/wars | Romanian Campaign, Russian Civil War, Polish-Soviet War |

| Awards | Order of the Red Banner |

Biography

Early life and the Russian Revolution

Anatolie Popa was born into a poor peasant family in Cotiujenii Mari, in the Soroksky Uyezd of the Bessarabia Governorate.[1][2] After primary education in his home village and Vadul-Rașcov, he enrolled in the Bălți municipal school. However, as his family was unable to cope with the high fees, he dropped out before graduating. Nevertheless, with the low literacy rate in Bessarabia, at 15 Popa was able to get a job as secretary of the rural police in his home village. This provided him with an occasion to become acquainted with the anti-Tsarist literature, mainly through the students returning home during the holidays.[2]

With the start of World War I, Popa was drafted in the Imperial Russian Army and, after graduating the Odessa War College as an officer, he was sent to the Eastern Front. He was supportive of the overthrow of the Tsar during the February Revolution, and his political views were further influenced by the strong Bolshevik agitation in the 49th Technical Reserve Battalion in Odessa, where he was recovering from a battlefield injury. Popa was eventually put in command of a battalion of the 75th Sevastopol Infantry Regiment and in September 1917 was dispatched to Chișinău, the Bessarabian administrative centre.[2]

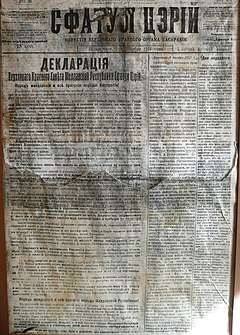

Popa soon joined the Moldavian national movement, which sought autonomy for Bessarabia, and was appointed a delegate to the Moldavian Central Military Executive Committee.[3] The movement for autonomy, spearheaded by the Moldavian National Party (MNP), was regarded with suspicion not only by the ethnic minorities, but also by the leftist revolutionary committees and the Moldavian peasant majority, who feared autonomy was a step towards annexation to the neighbouring conservative Kingdom of Romania.[4] The October Revolution, however, led to a mood change amongst the more moderate leftist groups, and in November 1917 the various revolutionary committees coagulated into a provisional provincial assembly, Sfatul Țării, which on 15 December [O.S. 2 December] proclaimed the autonomous Moldavian Democratic Republic within a Russian Democratic Federative Republic.[5]

The assembly, proclaiming itself the highest authority in Bessarabia, appointed a provisional executive, the Council of Directors; furthermore, it nominally pledged allegiance to the Provisional Government, placing itself in tacit opposition to the provincial and Chișinău city Soviets of workers' and soldiers' deputies, which had recognised the Bolshevik Council of People's Commissars (Sovnarkom) at the end of November.[6] As the latter commanded the allegiance of most regular troops of the Russian Army in Bessarabia, increasingly Bolshevik in outlook, the Council of Directors sought to enlist the Moldavian militias in an effort to create an Armed Force loyal to Sfatul Țării.[7] Anatolie Popa was among the officers chosen for this task and, on 28 December [O.S. 15 December], he received the command of the "nationalised" Moldavian 478th detachment of Bălți.[8][9] Popa was also appointed military commissioner for the Bălți county,[10] growing close to the local Council of peasants' deputies.[11] The state of emergency was soon declared in the Bălți county "in order to preserve public order", however Popa was reticent in using violence against the peasants. On 4 January 1918 [O.S. 22 December 1917], the Council's Military Director had to request the Commissioner for Moldavian Problems in Odessa to order Popa to comply with the directions issued by the local commissioner and commander of the garrison.[9]

Romanian intervention and defence of Bălți

The authority of Sfatul Țării was not universally recognised across Bessarabia; instead, several local committees, some loyal to the Sovnarkom, exercised authority locally. The most serious contender was the Chișinău City Soviet, which, radicalised by the Ukrainian Rada's demobilisation order, had elected a mostly Bolshevik executive committee in mid-December. The Soviet and the Council still collaborated in managing the demobilisation, however they were unable to cope with the disruption caused by the large number of disorganised, badly fed soldiers leaving the front.[12] Confronted with widespread peasant rioting and the unreliability of Moldavian troops, which were also siding with the Bolsheviks, a closed session of Sfatul Țării authorised the Council of Directors to look for military support outside the province: the leftist leaders, Ion Inculeț and Pantelimon Erhan, held talks with the chief of the Odessa Military District, while the nationalist MNP sought assistance from the Romanian government in Iași.[13] By 2 January 1918 [O.S. 20 December 1917], rumours of an imminent foreign military intervention had spread in Chișinău, prompting the Moldavian Military Central Executive Committee, the City Soviet and the provincial Peasants' Council to issue protests, affirming their commitment to the revolution and a federal Russia, and calling for redistributing land to peasants, purging the "reactionary" elements in Sfatul Țării and establishing relations with the Sovnarkom.[14] In spite of reassurances coming from the leaders of Sfatul Țării that only "neutral" troops would be brought, the provincial and Chișinău City soviets took steps toward strengthening their positions. On 6 January 1918 [O.S. 24 December 1917] they established a Revolutionary Headquarters, proclaimed the highest authority over all "Soviet" troops in Bessarabia, and soon they enlisted the support of the frontline department (Frontotdel) of the Rumcherod, which had arrived to Chișinău at the end of December.[14]

The Council of Directors also ultimately decided on 8 January 1918 [O.S. 26 December 1917] to request military assistance from General Dmitry Shcherbachev, the nominal head of Russian troops on the Romanian front; the general, who had no effective authority over the troops, forwarded the request to the Romanians. Several leaders of the Nationalist Party would later testify this was the intended course of events, the Council fearing a direct call for Romanian troops would result in a popular revolt.[15] The request precipitated a Bolshevik takeover, as, on 14 January [O.S. 1 January] 1918, the Frontotdel proclaimed itself the supreme authority over all troops in Bessarabia and took control of the mail, telegraph and main railway stations in Bessarabia. The authority of Sfatul Țării, declared an "organ of the bourgeoisie", was virtually dissolved.[16] In this context, the Romanian army moved in into Bessarabia in early January and occupied several towns and villages along the Prut, encountering only light resistance from local pro-Soviet troops. The first major encounter took place in Chișinău on 19 January [O.S. 6 January], when Moldavian and Russian troops disarmed troops of the Transylvanian volunteer corps sent by the Romanian government to take the city.[17] Later that day, Erhan and Inculeț, summoned at a joint meeting of the provincial and City soviets with the Moldavian Military Central Executive Committee, denied any role in the Romanian invasion, repudiated the MNP directors, and even agreed to send a protest note to the Romanian government, calling for a withdrawal of its troops.[17] The mood among the Moldavian troops was also strongly anti-Romanian, and Erhan and the Military Director, Gherman Pântea, were forced to authorise resistance; however, as the main corps of the Romanian army approached Chișinău on 20 January [O.S. 7 January], Pântea directed most Moldavian troops in the opposite direction in order to avert a battle.[18] While the initial Romanian forays into the Bessarabian capital were repulsed with difficulties by the Russian and Moldavian troops, the Frontodel and the City Soviet, faced with a numerically superior opponent, ultimately decided to withdraw towards Bender, and the Romanians occupied Chișinău on 26 January [O.S. 13 January].[19]

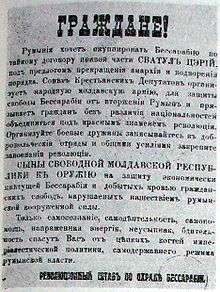

The news of the Romanian invasion quickly reached the rest of Bessarabia, and resistance was prepared, most notably in Bălți and Bender. On 21 January [O.S. 8 January], on the initiative of the Bălți County commissioner Vasile Rudiev, the county's Council of Peasants' Deputies began organising a resistance to the Romanian advance. The Council declared a general mobilisation and established the Revolutionary Headquarters for the Defence of the Country, comprising Andrei Paladi, chairman of the county's Land Committee, G. Galagan, member of the Provincial Peasant's Council executive committee, Rudiev, and others.[20][21][22][23] Already on the 22nd, the Revolutionary Headquarters was able to muster 3,000 workers and soldiers of the local garrison, who held a rally also attended by delegates from nearby villages.[21] The mobilisation was not however supported by all the committees: the Bălți Municipal Council rejected it on 23 January [O.S. 10 January] January, refused to send delegates to the Revolutionary Headquarters and event requested its dissolution. Its delegates to the 22 January [O.S. 9 January] joint session of the Peasants' Council, the Municipal Council, the Workers' and Soldiers' Soviet and the county zemstvo were even able to obtain a slight majority against armed resistance.[23] According to his own account, the chairman of the local Soviet, the Menshevik Razumovskyi, also attempted to delay the mobilisation, arguing that a hastily armed crowd would not be able to resist a regular army; however, his attempts to persuade the 27 January [O.S. 14 January] session of the Peasants' Council were received with jeers.[24] In spite of such opposition, Rudiev and Popa, who replaced the former in the Revolutionary Headquarters, handed out weapons to volunteers in the city and nearby villages and ensured that the two artillery pieces available to the garrison were properly manned.[20][25] According to a witness interrogated by the Romanians after taking the city, the local Revolutionary Committee, led by sub-lieutenant Solovyov, requested Popa to hand in the weapons from the garrison, threatening him with death;[26] another witness however indicated that Popa acted on its own accord, handing out weapons personally, in collaboration with other members of the Revolutionary Headquarters.[27] Popa also took into custody several Romanian officers arrested in the countryside, and rejected Razumovskyi's plea for their release, stating he was acting in retaliation to the arrest of Moldavian officers in Ungheni.[24]

The Second Congress of the Bălți County Peasants' deputies, held on 27 January [O.S. 14 January], voted to reject the authority of Sfatul Țării as unrepresentative, pledged allegiance to the Bolshevik Sovnarkom and called for the institution of Soviet power. Furthermore, the Congress rejected Bessarabia's separation from Soviet Russia and decided to send Paladi to Petrograd to request for military assistance against the Romanian intervention.[28][29] The call for an end to the Romanian intervention was initially joined by the Third Bessarabian Peasants' Congress, assembled in Chișinău on 31 January [O.S. 18 January] and presided by Rudiev. However, as the latter city had already been occupied by Romanian troops, the radical leaders of the Congress were arrested and executed shortly after; a more complacent leadership was installed and renounced overt opposition to the Romanian military occupation.[30][31] According to the pro-Romanian politician Dimitrie Bogos, Popa also attended the Provincial Congress in Chișinău on the 31st [O.S. 18th], where he sided with the initial majority, and only afterwards returned to Bălți and began organising the resistance against the Romanian army.[32]

Popa also contacted Gherman Pântea, the acting Director for the military of the provisional Bessarabian executive, requesting information about the situation in Chișinău. According to the transcript of their 2 February [O.S. 20 January] exchange, Popa had managed to enlist an infantry battalion, two cavalry squadrons, a machine-gun company, a motor transport company, as well as an artillery battery. Noting that the population was outraged by the Romanian intervention and the Peasants' Council had switched allegiance to the Petrograd government, he requested more officers and money for the soldiers' pay, and offered to send ammunitions and even troops to Chișinău. In his reply, Pântea repeated the Romanian argument that their intervention was only meant to protect the supply depots and pacify the capital, and expressed his distrust of the Bolshevik government. However, he also noted the Moldavian troops' dissatisfaction with the Romanian presence and affirmed his commitment to a republican Bessarabia "alongside Russia". Furthermore, Pântea informed Popa about his intention to resign from the executive, as the latter was becoming increasingly pro-Romanian, as well as his decision to mobilise the Moldavian Army to defend the country in case "someone looks over the Prut", towards the Romanian government.[33][34][35]

Between 3 and 5 February [O.S. 21 and 23 January], Moldavian and Russians troops, led by the Revolutionary Headquarters, defended Bălți against the Romanian offensive.[32] The defenders of the city, comprising up to a thousand volunteers and the revolutionary troops in the garrison, were also joined by armed peasants from Cubolta, Hăsnășenii Mici and other nearby villages. The initial advance of the Romanian 1st Cavalry Division commanded by general Mihail Schina was temporarily repulsed with losses at Fălești, with the general himself briefly captured by a peasants self-defense group in Obreja on 4 February [O.S. 22 January]. The same day the Romanians attempted to enter the city, but, coming under machine gun and artillery fire, they retreated with heavy losses; another Romanian cavalry detachment was repulsed near the railway station. Superior both in number of troops and artillery, the Romanian troops were ultimately able to defeat the revolutionary detachments and capture the town in the afternoon of 5 February [O.S. 23 January], with part of the defenders retreating toward the north.[36][32][11][20] Soviet sources also indicate the counter-revolutionary forces acting inside Bălți as a factor in the defeat.[11] The Romanian occupation forces immediately began a crackdown on the resistance, with 20 locals executed and more than one thousand arrested in the following two days.[11][20] Anatolie Popa was also apprehended on the occasion and, on 14 February [O.S. 1 February], was sentenced to death by a Court Martial for his role in organising and arming the local troops.[11][32][37][38] The assessment of the battle was mixed: while the Soviet historiography praised the Defence of Bălți as a heroic deed,[28] Bogos saw the battle as an "infamy" comparable to the events of January 6, when Moldavian troops in Chișinău disarmed the Transylvanian volunteer corps.[32] As argued by historian Izeaslav Levit, the opponents of the Romanian intervention included people of different ethnic backgrounds and political options: while the chairman of the local Soviet, the Ukrainian lieutenant Soloviev, collaborated with the Revolutionary Headquarters chiefly in order to prevent its takeover by the Bolsheviks, the Moldavians Rudiev and Popa were primarily supporters of the Moldavian autonomy and of peasants' interest, pushed into collaboration with the Bolsheviks by what they saw as their betrayal by the right wing of the Sfatul Țării.[39]

Russian Civil War and death

Owing to Popa's good standing with the Bessarabian population, the Romanian authorities sought to co-opt him in their administration; consequently, he was soon pardoned by King Ferdinand and offered a position in the Romanian Army.[32][1][38] Anatol Popa however took the occasion and fled over the Dniester, to Ukraine, joining the Soviet partisan groups. Given a command position, he led a partisan detachment that crossed the Dniester back into Bessarabia during the Khotin Uprising in January 1919. After the Romanian Army violently suppressed the rebellion, he returned to Ukraine, where his group engaged troops loyal to the Directorate.[11][1][37][40]

By April 1919, Popa was appointed commander of the first infantry regiment of the 1st Bessarabian brigade, led by Filip Levenson. This Red Army unit included many participants in the Khotin Uprising, and was later redesignated as a Special Bessarabian Brigade and in June was integrated into the newly organised 45th Soviet Rifle Division. Under the command of Bessarabian Yona Yakir, the division fought in the Southern Campaign of the Russian Civil War; after the fall of Odessa, it took a 400 kilometre march across enemy lines, engaging along the way the forces of Yudenich, Denikin and Makhno.[11][1] On February 13, 1920, Anatolie Popa was given the command of the 399th Regiment "Communist" of the 45th Division, which was sent to the Polish front, suffering heavy losses. Replenished to a full strength of 400, on March 23 the regiment was ordered to capture the settlement of Novo-Miropol'. The assault encountered strong resistance and Popa, heavily wounded, was captured by the Polish forces. He died under interrogation before the Soviets were able to take the town, three days later.[41][42][43] Posthumously awarded the Order of the Red Banner, Popa was praised by Yakir in his 1929 memoirs as a "titan commander" who "possessed both great willpower and great endurance".[41]

Notes

- Nazaria 2012, p. 209.

- Abakumova & Esaulenko 1987, p. 107.

- Kalinenok & Esaulenko 1982, p. 139.

- Levit 2000, p. 2.

- Levit 2000, p. 19.

- Levit 2000, pp. 27–28,44–45.

- Levit 2000, pp. 65–67.

- Halipa 1991, pp. 75–76.

- Ciobanu 2010, p. 116.

- Bogos 1998, p. 153.

- Abakumova & Esaulenko 1987, p. 108.

- Levit 2000, pp. 113–120,125–126.

- Levit 2000, pp. 179–180.

- Levit 2000, pp. 186–190.

- Levit 2000, pp. 192–197.

- Levit 2000, pp. 207–209,213–217.

- Levit 2000, pp. 219–224.

- Levit 2000, pp. 227–229.

- Levit 2000, pp. 232,242,253.

- Shornikov 2011, p. 25.

- Tsaranov 1984, p. 266.

- Levit 2000, pp. 229–231.

- Bereznyakov 1967, p. 48, footnote 1.

- Bereznyakov 1967, p. 47-48, Doc. 33.

- Levit 2000, p. 231.

- Bereznyakov 1967, p. 50, Doc. 34.

- Bereznyakov 1967, p. 43, Doc. 29.

- Tsaranov 198, p. 267.

- Levit 2000, p. 254.

- Tsaranov 1984, p. 267.

- Levit 2000, pp. 256–263.

- Bogos 1998, p. 154.

- Bereznyakov 1970, pp. 45–47, Doc. 41.

- Bogos 1998, pp. 154–156.

- Levit 2000, pp. 265–268.

- Polivțev 2017, pp. 387–388.

- Bereznyakov 1967, p. 43, footnote 1.

- Polivțev 2017, p. 388.

- Levit 2000, p. 232.

- Polivțev 2017, pp. 388–389.

- Abakumova & Esaulenko 1987, p. 109.

- Kalinenok & Esaulenko 1982, pp. 137–138.

- Polivțev 2017, p. 389.

References

- Berezniakov, Nikolay Vasil'evich, ed. (1967). Борьба трудящихся Молдавии против интервентов и внутренней контрреволюции в 1917–1920 гг. [The struggle of the working people of Moldova against the interventionists and internal counterrevolution in 1917–1920] (in Russian). Kishinev: Cartea Moldovenească.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Bereznyakov, Nikolay Vasil'evich, ed. (1970). За власть Советскую : Борьба трудящихся Молдавии против интервентов и внутренней контрреволюции (1917–1918 гг.) [For the power of the Soviets: The struggle of the working people of Moldova against the interventionists and internal counterrevolution (1917–1918)] (in Russian). Kishinev: Academy of Sciences of the Moldavian SSR.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kalinenok, Marat Alexandrovich; Esaulenko, A. (1982). Активные участники борьбы за власть Советов в Молдавии [Active participants in the struggle for the power of the Soviets in Moldova] (in Russian). Kishinev: Știința.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Tsaranov, Vladimir Ivanovich, ed. (1984). История Молдавской ССР с древнейших времен до наших дней [History of the Moldavian SSR from ancient times to the present day] (in Russian). Kishinev: Știința.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Abakumova, N.; Esaulenko, A. (1987). Попа, Анатолий Васильевич [Popa, Anatoliy Vasilievich]. In Shemyakov, Dmitriy Egorovich (ed.). Борцы за счастье народное : Сб. документ. очерков [Fighters for the happiness of the people: Collection of documentary sketches] (in Russian). Kishinev: Cartea Moldovenească.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Halipa, Pantelimon; Moraru, Anatolie (1991). Testament pentru urmași [A testament for the future generations] (in Romanian). Chișinău: Hyperion. ISBN 5-368-01446-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Bogos, Dimitrie (1998). La răspântie : Moldova de la Nistru 1917-1918 [At the crossroads: Moldavia on the Dniester 1917-1918] (in Romanian). Chișinău: Știința. ISBN 9975-67-056-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Levit, Izeaslav (2000). Год судьбоносный : от провозглашения Молдавской республики до ликвидации автономии Бессарабии : (ноябрь 1917 - ноябрь 1918 г.) [The fateful year: from the proclamation of the Moldavian Republic to the abolition of the Bessarabian autonomy: (November 1917 – November 1918)] (in Russian). Chișinău: Tipografia Centrală. ISBN 9975-78-057-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Ciobanu, Vitalie (2010). Militarii Basarabeni 1917-1918 : Studiu și documente [The Bessarabian military 1917-1918: Study and documents] (in Romanian). Chișinău: Bons Offices. ISBN 978-9975-80-330-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Shornikov, Petr Mihaylovich (2011). Бессарабский фронт (1918-1940 гг.) [The Bessarabian Front (1918-1940)] (in Russian) (2nd ed.). Tiraspol: Poligrafist.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Nazaria, Sergiu (2012). O istorie contra miturilor: relațiile internaționale în epoca războaielor mondiale (1914-1945/1947) [A history against myths: international relations in the era of the world wars (1914-1945/1947)] (in Romanian). Chișinău: Tipografia Centrală. ISBN 978-9975-53-115-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Polivțev, Vladimir (2017). "На защите завоеваний революции и воссоздаваемой Молдавской Государственности (1917-1918 гг.)" [In protection of the revolution results and restructuring of Moldovan statehood (1917-1918)] (PDF). In Beniuc, Valentin; et al. (eds.). Statalitatea Moldovei: continuitatea istorică și perspectiva dezvoltării. Chișinău: International Relations Institute of Moldova. pp. 354–391. ISBN 978-9975-56-439-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)