American barn owl

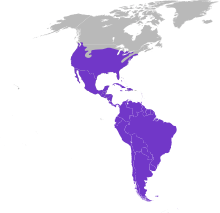

The American barn owl (Tyto furcata) is usually considered a subspecies group and together with the western barn owl group, the eastern barn owl group, and sometimes the Andaman masked owl, make up the barn owl, cosmopolitan in range. The barn owl is recognized by most taxonomic authorities. A few (including the International Ornithologists' Union) separate them into distinct species, as is done here. The American barn owl is native to North and South America, and has been introduced to Hawaii.

| American barn owl | |

|---|---|

.jpg) | |

| Tyto furcata in Utah | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Strigiformes |

| Family: | Tytonidae |

| Genus: | Tyto |

| Species: | T. furcata |

| Binomial name | |

| Tyto furcata (Temminck, 1827) | |

| Subspecies | |

|

Many, see text | |

| |

| Synonyms | |

|

Strix pratincola Bonaparte, 1838 | |

The ashy-faced owl (T. glaucops) was for some time included in T. alba, and by some authors its populations from the Lesser Antilles still are. Based on DNA evidence, König, Weick & Becking (2009) recognised the American barn owl (T. furcata) and the Curaçao barn owl (T. bargei) as separate species.[1]

Description

The American barn owl is a medium-sized, pale-coloured owl with long wings and a short, squarish tail. However, the largest bodied race of barn owl, T. f. furcata from Cuba and Jamaica, is also an island race, albeit being found on more sizeable islands with larger prey and few larger owls competing for dietary resources.[2] The shape of the tail is a means of distinguishing the barn owl from typical owls when seen in the air. Other distinguishing features are the undulating flight pattern and the dangling, feathered legs. The pale face with its heart shape and black eyes give the flying bird a distinctive appearance, like a flat mask with oversized, oblique black eye-slits, the ridge of feathers above the beak somewhat resembling a nose.[3]

The bird's head and upper body typically vary between pale brown and some shade of grey (especially on the forehead and back) in most subspecies. Some are purer, richer brown instead, and all have fine black-and-white speckles except on the remiges and rectrices (main wing feathers), which are light brown with darker bands. The heart-shaped face is usually bright white, but in some subspecies it is brown. The underparts, including the tarsometatarsal (lower leg) feathers, vary from white to reddish buff among the subspecies, and are either mostly unpatterned or bear a varying number of tiny blackish-brown speckles. It has been found that at least in the continental European populations, females with more spotting are healthier than plainer birds. This does not hold true for European males by contrast, where the spotting varies according to subspecies. The beak varies from pale horn to dark buff, corresponding to the general plumage hue, and the iris is blackish brown. The talons, like the beak, vary in colour, ranging from pink to dark pinkish-grey and the talons are black.[4]

On average within any one population, males tend to have fewer spots on the underside and are paler in colour than females. The latter are also larger with a strong female T. alba of a large subspecies weighing over 550 g (19.4 oz), while males are typically about 10% lighter. Nestlings are covered in white down, but the heart-shaped facial disk becomes visible soon after hatching.[5]

In the United States, dispersal is typically over distances of 80 and 320 km (50 and 199 mi), with the most travelled individuals ending up some 1,760 km (1,094 mi) from the point of origin. The barn owl has been successfully introduced into the Hawaiian island of Kauai in an attempt to control rodents; however, it has been found to also feed on native birds.[6]

Behaviour and ecology

Like most owls, it is nocturnal, relying on its acute sense of hearing when hunting in complete darkness. It often becomes active shortly before dusk and can sometimes be seen during the day when relocating from one roosting site to another. Barn owls are not particularly territorial but have a home range inside which they forage. Female home ranges largely coincide with that of their mates. Outside the breeding season, males and females usually roost separately, each one having about three favoured sites in which to conceal themselves by day, and which are also visited for short periods during the night. Roosting sites include holes in trees, fissures in cliffs, disused buildings, chimneys and haysheds and are often small in comparison to nesting sites. As the breeding season approaches, the birds move back to the vicinity of the chosen nest to roost.[7]

It is a bird of open country such as farmland or grassland with some interspersed woodland, usually at altitudes below 2,000 metres (6,600 ft) but occasionally as high as 3,000 metres (9,800 ft) in the tropics. This owl prefers to hunt along the edges of woods or in rough grass strips adjoining pasture. It has an effortless wavering flight as it quarters the ground, alert to the sounds made by potential prey. Like most owls, the barn owl flies silently; tiny serrations on the leading edges of its flight feathers and a hairlike fringe to the trailing edges help to break up the flow of air over the wings, thereby reducing turbulence and the noise that accompanies it. Hairlike extensions to the barbules of its feathers, which give the plumage a soft feel, also minimise noise produced during wingbeats.[8]

Diet and feeding

.jpg)

The diet of the barn owl has been much studied; the items consumed can be ascertained from identifying the prey fragments in the pellets of indigestible matter that the bird regurgitates. Studies of diet have been made in most parts of the bird's range, and in moist temperate areas over 90% of the prey tends to be small mammals, whereas in hot, dry, unproductive areas, the proportion is lower, and a great variety of other creatures are eaten depending on local abundance. Most prey is terrestrial but bats and birds are also taken, as well as lizards, amphibians and insects. Even when they are plentiful and other prey scarce, earthworms do not seem to be consumed.[9]

In North America, voles predominate in the diet and shrews are the second most common food choice. On a rocky islet off the coast of California, a clutch of four young were being reared on a diet of Leach's storm petrel (Oceanodroma leucorhoa).[10] Locally superabundant rodent species in the weight class of several grams per individual usually make up the single largest proportion of prey.[11] In the United States, rodents and other small mammals usually make up ninety-five percent of the diet[12] and worldwide, over ninety percent of the prey caught.[13][14]

The barn owl hunts by flying slowly, quartering the ground and hovering over spots that may conceal prey. It may also use branches, fence posts or other lookouts to scan its surroundings. The bird has long, broad wings, enabling it to manoeuvre and turn abruptly. Its legs and toes are long and slender which improves its ability to forage among dense foliage or beneath the snow and gives it a wide spread of talons when attacking prey.[8] Studies have shown that an individual barn owl may eat one or more voles (or their equivalent) per night, equivalent to about twenty-three percent of the bird's bodyweight. Excess food is often cached at roosting sites and can be used when food is scarce.[15]

Small prey is usually torn into chunks and eaten completely including bones and fur, while prey larger than about 100 g (4 oz), such as baby rabbits, Cryptomys blesmols, or Otomys vlei rats, is usually dismembered and the inedible parts discarded. Contrary to what is sometimes assumed, the barn owl does not eat domestic animals on any sort of regular basis. Regionally, non-rodent foods are used as per availability. On bird-rich islands, a barn owl might include some fifteen to twenty percent of birds in its diet, while in grassland it will gorge itself on swarming termites, or on Orthoptera such as Copiphorinae katydids, or true crickets (Gryllidae). Bats and even frogs, lizards and snakes may make a minor but significant contribution to the diet.

It has acute hearing, with ears placed asymmetrically. This improves detection of sound position and distance and the bird does not require sight to hunt. The facial disc plays a part in this process, as is shown by the fact that with the ruff feathers removed, the bird can still locate the source in azimuth but fails to do so in elevation.[16] Hunting nocturnally or crepuscularly, this bird can target its prey and dive to the ground, penetrating its talons through snow, grass or brush to seize small creatures with deadly accuracy. Compared to other owls of similar size, it has a much higher metabolic rate, requiring relatively more food. Weight for weight, they consume more rodents—often regarded as pests by humans—than possibly any other creature. This makes the barn owl one of the most economically valuable wildlife animals for agriculture. Farmers often find these owls more effective than poison in keeping down rodent pests.

Breeding

Barn owls living in tropical regions can breed at any time of year, but some seasonality in nesting is still evident. Where there are distinct wet and dry seasons, egg-laying usually takes place during the dry season, with increased rodent prey becoming available to the birds as the vegetation dies off. In arid regions, breeding may be irregular and may happen in wet periods, triggered by temporary increases in the populations of small mammals. In temperate climates, nesting seasons become more distinct and there are some seasons of the year when no egg-laying takes place. In North America, most nesting takes place between March and June when temperatures are increasing. The actual dates of egg-laying vary by year and by location, being correlated with the amount of prey-rich foraging habitat around the nest site and often with the phase of the rodent abundance cycle.[17]

Females are ready to breed at 10 to 11 months of age although males sometimes wait till the following year. Barn owls are usually monogamous, sticking to one partner for life unless one of the pair dies. During the non-breeding season they may roost separately, but as the breeding season approaches they return to their established nesting site, showing considerable site fidelity. In colder climates, in harsh weather and where winter food supplies may be scarce, they may roost in farm buildings and in barns between hay bales, but they then run the risk that their selected nesting hole may be taken over by some other, earlier-nesting species. Single males may establish feeding territories, patrolling the hunting areas, occasionally stopping to hover, and perching on lofty eminences where they screech to attract a mate. Where a female has lost her mate but maintained her breeding site, she usually seems to manage to attract a new spouse.[18]

Once a pair-bond has been formed, the male will make short flights at dusk around the nesting and roosting sites and then longer circuits to establish a home range. When he is later joined by the female, there is much chasing, turning and twisting in flight, and frequent screeches, the male's being high-pitched and tremulous and the female's lower and harsher. At later stages of courtship, the male emerges at dusk, climbs high into the sky and then swoops back to the vicinity of the female at speed. He then sets off to forage. The female meanwhile sits in an eminent position and preens, returning to the nest a minute or two before the male arrives with food for her. Such feeding behaviour of the female by the male is common, helps build the pair-bond and increases the female's fitness before egg-laying commences.[18]

Barn owls are cavity nesters. They choose holes in trees, fissures in cliff faces, the large nests of other birds and old buildings such as farm sheds and church towers. Trees tend to be in open habitats rather than in the middle of woodland and nest holes tend to be higher in North America because of possible predation by raccoons (Procyon lotor). No nesting material is used as such but, as the female sits incubating the eggs, she draws in the dry furry material of which her regurgitated pellets are composed, so that by the time the chicks are hatched, they are surrounded by a carpet of shredded pellets.

Before commencing laying, the female spends much time near the nest and is entirely provisioned by the male. Meanwhile, the male roosts nearby and may cache any prey that is surplus to their requirements. When the female has reached peak weight, the male provides a ritual presentation of food and copulation occurs at the nest. The female lays eggs on alternate days and the clutch size averages about five eggs (range two to nine). The eggs are chalky white, somewhat elliptical and about the size of bantam's eggs, and incubation begins as soon as the first egg is laid. While she is sitting on the nest, the male is constantly bringing more provisions and they may pile up beside the female. The incubation period is about 30 days, hatching takes place over a prolonged period and the youngest chick may be several weeks younger than its oldest sibling. In years with plentiful supplies of food, there may be a hatching success rate of about 75%. The male continues to copulate with the female when he brings food which makes the newly hatched chicks vulnerable to injury.[18]

The chicks are at first covered with greyish-white down and develop rapidly. Within a week they can hold their heads up and shuffle around in the nest. The female tears up the food brought by the male and distributes it to the chicks. Initially these make a "chittering" sound but this soon changes into a food-demanding "snore". By two weeks old they are already half their adult weight and look naked as the amount of down is insufficient to cover their growing bodies. By three weeks old, quills are starting to push through the skin and the chicks stand, making snoring noises with wings raised and tail stumps waggling, begging for food items which are now given whole. The male is the main provider of food until all the chicks are at least four weeks old at which time the female begins to leave the nest and starts to roost elsewhere. By the sixth week the chicks are as big as the adults but have slimmed down somewhat by the ninth week when they are fully fledged and start leaving the nest briefly themselves. They are still dependent on the parent birds until about 13 weeks and receive training from the female in finding, and eventually catching, prey.[18]

Moulting

Feathers become abraded over time and all birds need to replace them at intervals. Barn owls are particularly dependent on their ability to fly quietly and manoeuvre efficiently, and in temperate areas their prolonged moult lasts through three phases over a period of two years. The female starts to moult while incubating the eggs and brooding the chicks, a time when the male feeds her so she does not need to fly much. The first primary feather to be shed is the central one, number 6, and it has regrown completely by the time the female resumes hunting. Feathers 4, 5, 7 and 8 are dropped at a similar time the following year and feathers 1, 2, 3, 9 and 10 in the bird's third year of adulthood. The secondary and tail feathers are lost and replaced over a similar timescale, again starting while incubation is taking place. In the case of the tail, the two outermost tail feathers are first shed followed by the two central ones, the other tail feathers being moulted the following year.[19]

In temperate areas, the male owl moults rather later in the year than the female, at a time when there is an abundance of food, the female has recommenced hunting and the demands of the chicks are lessening. Unmated males without family responsibilities often start losing feathers earlier in the year. The moult follows a similar prolonged pattern to that of the female and the first sign that the male is moulting is often when a tail feather has been dropped at the roost.[19] A consequence of moulting is the loss of thermal insulation. This is of little importance in the tropics and barn owls here usually moult a complete complement of flight feathers annually. The hot-climate moult may still take place over a long period but is usually concentrated at a particular time of year outside the breeding season.[20]

Predators and parasites

Predators of the barn owl include large American opossums (Didelphis), the common raccoon, and similar carnivorous mammals, as well as eagles, larger hawks and other owls. Among the latter, the great horned owl (Bubo virginianus) is a noted predator of barn owls. Despite some sources claiming that there is little evidence of predation by great horned owls, one study from Washington found that 10.9% of the local great horned owl's diet was made up of barn owls.[21][22][23]

When disturbed at its roosting site, an angry barn owl lowers its head and sways it from side to side, or the head may be lowered and stretched forward and the wings drooped while the bird emits hisses and makes snapping noises with its beak. A defensive attitude involves lying flat on the ground or crouching with wings spread out.[24]

Lifespan

Unusually for such a medium-sized carnivorous animal, the barn owl exhibits r-selection, producing large number of offspring with a high growth rate, many of which have a relatively low probability of surviving to adulthood.[25] While wild barn owls are thus decidedly short-lived, the actual longevity of the species is much higher – captive individuals may reach twenty years of age or more. But occasionally, a wild bird reaches an advanced age. The American record age for a wild barn owl is eleven and a half years. Taking into account such extremely long-lived individuals, the average lifespan is about four years, and statistically two-thirds to three-quarters of all adults survive from one year to the next.

The most significant cause of death in temperate areas is likely to be starvation, particularly over the autumn and winter period when first year birds are still perfecting their hunting skills. In northern and upland areas, there is some correlation between mortality in older birds and adverse weather, deep-lying snow and prolonged low temperatures. Collision with road vehicles is another cause of mortality, and may result when birds forage on mown media strips and shoulders. Some of these birds are in poor condition and may have been less able to evade oncoming vehicles than fit individuals would have been. Historically, many deaths were caused by the use of pesticides, and this may still be the case in some parts of the world. Collisions with power-lines kill some birds.

Subspecies

In Handbook of Birds of the World Volume 5: Barn-owls to Hummingbirds, the following subspecies are listed:[4]

| Subspecies | Description | Range | Synonyms |

|---|---|---|---|

T. f. furcata (Temminck, 1827)  In Cuba | Large. Upperparts pale orange-buff and brownish-grey, underparts whitish with few speckles. Face white.[4] | Cuba, Jamaica, the Cayman Islands (rare or extinct on Grand Cayman).[26] | Caribbean barn owl – might include niveicauda. |

T. f. tuidara (J.E. Gray, 1829).jpg) In Brazil | Upperparts grey and orange-buff. Underparts whitish to light buff with little speckling. Face white. Resembles pale Old World Tyto alba guttata.[4] | South American lowlands east of the Andes and south of the Amazon River all the way south to Tierra del Fuego; also on the Falkland Islands.[4] | Includes hauchecornei and possibly hellmayri. |

T. f. pratincola (Bonaparte, 1838)  Adult in flight | Large. Upperparts grey and orange-buff. Underparts whitish to light buff with much speckling. Face white. Resembles pale Old World T. a. guttata, but usually more speckles below.[4] | North America from southern Canada south to central Mexico; Bermuda, the Bahamas, Hispaniola; introduced to Lord Howe Island (where it was extirpated) and in 1958 to Hawaii (where it still lives).[4] | North American barn owl – includes lucayana and might also include bondi, guatemalae and subandeana. |

T. f. punctatissima (G. R. Grey, 1838)  On Santa Cruz Island (the Galápagos Islands) | Small. Dark greyish-brown above, with white part of spots prominent. Underparts white to golden-buff, with distinct pattern of brown vermiculations or fine dense spots.[4] | Endemic to the Galápagos islands.[4] | Galápagos barn owl - sometimes considered a separate species. |

| T. f. guatemalae (Ridgway, 1874) | Similar to dark pratincola; less grey above, coarser speckles below.[4] | Guatemala or southern Mexico through Central America to Panama or northern Colombia; the Pearl Islands.[4] | Includes subandeana; doubtfully distinct from pratincola. |

| T. f. bargei (Hartert, 1892) | Similar to alba; smaller and noticeably short-winged.[4] | Endemic to Curaçao and maybe Bonaire in the West Indies.[4] |

Curącao barn owl - sometimes considered a separate species. |

| T. f. contempta (Hartert, 1898) | Almost black with some dark grey above, the white part of the spotting showing prominently. Reddish-brown below.[4] | Northeastern Andes from western Venezuela through eastern Colombia (rare in the Cordillera Central and Cordillera Occidental)[27] south to Peru.[4] | Includes stictica. |

| T. f. hellmayri (Griscom & Greenway, 1937) | Similar to tuidara, but larger.[4] | Northeastern South American lowlands from eastern Venezuela south to the Amazon River.[4] | Doubtfully distinct from tuidara. |

| T. f. bondi (Parks & Phillips, 1978) | Similar to pratincola; smaller and paler on average.[4] | Endemic to Roatán and Guanaja in the Bay Islands.[4] | Doubtfully distinct from pratincola. |

| T. f. niveicauda (Parks & Phillips, 1978) | Large. Similar to furcata; paler in general. Resembles Old World T. a. alba.[4] | Endemic to Isla de la Juventud.[4] | Doubtfully distinct from furcata. |

Status and conservation

Barn owls are relatively common throughout most of their range and not considered globally threatened. However, locally severe declines from organochlorine (e.g., DDT) poisoning in the mid-20th century and rodenticides in the late 20th century have affected some populations, particularly in North America. Intensification of agricultural practices often means that the rough grassland that provides the best foraging habitat is lost.[28] While barn owls are prolific breeders and able to recover from short-term population decreases, they are not as common in some areas as they used to be. In the US, barn owls are listed as endangered species in seven Midwestern states.

In some areas, it may be an insufficiency of suitable nesting sites that is the factor limiting barn owl numbers. The provision of nest boxes under the eaves of buildings and in other locations can be very successful in increasing the local population.

Common names such as "demon owl", "death owl", or "ghost owl" show that traditionally, rural populations in many places considered barn owls to be birds of evil omen. Consequently, they were often persecuted by farmers who were unaware of the benefits these birds bring to farms.[29]

References

- König, Claus; Weick, Friedhelm; Becking, Jan-Hendrik (2009). Owls of the World. Bloomsbury Publishing. pp. 46–48. ISBN 978-1-4081-0884-0.

- Owls of the World: A Photographic Guide by Mikkola, H. Firefly Books (2012), ISBN 9781770851368

- Bruce (1999) pp 34–75, Svensson et al. (1999) pp. 212–213

- Bruce (1999) pp. 34–75

- Taylor (2004) p. 169

- Denny, Jim (2006). "Introduced birds: Barn owl". Birds of Kaua'i. Retrieved 2014-07-24.

- Taylor (2004) pp. 96–107

- Taylor (2004) pp. 47–61

- Taylor (2004) pp. 29–46

- Bonnot, Paul (1928). "An outlaw Barn Owl" (PDF). Condor. 30 (5): 320. doi:10.2307/1363231. JSTOR 1363231.

- Laudet, Frédéric; Denys, Christiane; Senegas, Frank (2002). "Owls, multirejection and completeness of prey remains: implications for small mammal taphonomy" (PDF). Acta Zoologica Cracoviensia. 45: 341–355.

- Ingles, Chuck (1995). "Summary of California studies analyzing the diet of barn owls". Sustainable Agriculture/Technical Reviews. 2: 14–16. Archived from the original on November 28, 2011.

- Taylor (2004) p. 29

- Lavariega, Mario C.; García-Meza, Josué; Martínez-Ayón, Yazmín del Mar; Camarillo-Chávez, David; Hernández-Velasco, Teresa; Briones-Salas, Miguel (2015). "Análisis de las presas de la Lechuza de Campanario (Tytonidae) en Oaxaca Central, México". Neotropical Biology and Conservation (in Spanish). 11 (1). doi:10.4013/nbc.2016.111.03. ISSN 2236-3777.

- Taylor (2004) pp. 91–95

- Knudsen, Eric I.; Konishi, Masakazu (1979). "Mechanisms of sound localization in the barn owl (Tyto alba)". Journal of Comparative Physiology. 133 (1): 13–21. doi:10.1007/BF00663106.

- Taylor (2004) pp. 121–135

- Shawyer (1994) pp. 67–87

- Shawyer (1994) pp. 88–90

- Taylor (2004) pp. 108–120

- Marti, Carl D.; Poole, Alan F.; Bevier, L. R. (2005): Barn Owl (Tyto alba) The Birds of North America Online (A. Poole, Ed.). Ithaca: Cornell Lab of Ornithology; Barn owl

- Millsap, B. A. and P. A. Millsap. 1987. Burow nesting by common Barn Owls in north central Colorado. Condor no. 89:668-670.

- Knight, R. L.; Jackman, R. E. (1984). "Food-niche relationships between Great Horned Owls and Common Barn-Owls in eastern Washington". Auk. 101: 175–179.

- Witherby (1943) pp. 343–347

- Altwegg, Res; Schaub, Michael; Roulin, Alexandre (2007). "Age‐specific fitness components and their temporal variation in the barn owl". The American Naturalist. 169 (1): 47–61. doi:10.1086/510215. PMID 17206584.

- Olson, Storrs L.; James, Helen F.; Meister, Charles A. (1981). "Winter field notes and specimen weights of Cayman Island Birds" (PDF). Bulletin of the British Ornithologists' Club. 101 (3): 339–346.

- Krabbe, Niels; Flórez, Pablo; Suárez, Gustavo; Castaño, José; Arango, Juan David; Duque, Arley (2006). "The birds of Páramo de Frontino, western Andes of Colombia" (PDF). Ornitología Colombiana. 4: 39–50. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-09-24. Retrieved 2017-05-06.

- Taylor (2004) pp. 242–261

- Spence, Cindy (1999-10-28). "Spooky owl provides natural rodent control for farmers". UF News. University of Florida. Archived from the original on 2014-03-07. Retrieved 2014-07-14.

Bibliography

- Bruce, M. D. (1999). "Family Tytonidae (Barn-owls)". In del Hoyo, J.; Elliott, A.; Sargatal, J. (eds.). Handbook of Birds of the World Volume 5: Barn-owls to Hummingbirds. Lynx Edicions. ISBN 84-87334-25-3.

Further reading

- Aliabadian, M.; Alaei-Kakhki, N.; Mirshamsi, O.; Nijman, V.; Roulin, A. (2016). "Phylogeny, biogeography, and diversification of barn owls (Aves: Strigiformes)". Biological Journal of the Linnean Society. 119: 904–918. doi:10.1111/bij.12824.

External links

- Barn owl—USGS Patuxent Bird Identification InfoCenter

- Barn owl species account—Cornell Lab of Ornithology