Ambulance

An ambulance is a medically equipped vehicle which transports patients to treatment facilities, such as hospitals.[1] Typically, out-of-hospital medical care is provided to the patient.

Ambulances are used to respond to medical emergencies by emergency medical services. For this purpose, they are generally equipped with flashing warning lights and sirens. They can rapidly transport paramedics and other first responders to the scene, carry equipment for administering emergency care and transport patients to hospital or other definitive care. Most ambulances use a design based on vans or pick-up trucks. Others take the form of motorcycles, cars, buses, aircraft and boats.

Generally, vehicles count as an ambulance if they can transport patients. However, it varies by jurisdiction as to whether a non-emergency patient transport vehicle (also called an ambulette) is counted as an ambulance. These vehicles are not usually (although there are exceptions) equipped with life-support equipment, and are usually crewed by staff with fewer qualifications than the crew of emergency ambulances. Conversely, EMS agencies may also have emergency response vehicles that cannot transport patients.[2] These are known by names such as nontransporting EMS vehicles, fly-cars or response vehicles.

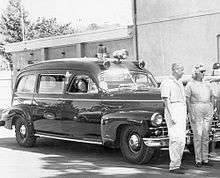

The term ambulance comes from the Latin word "ambulare" as meaning "to walk or move about"[3] which is a reference to early medical care where patients were moved by lifting or wheeling. The word originally meant a moving hospital, which follows an army in its movements.[4] Ambulances (Ambulancias in Spanish) were first used for emergency transport in 1487 by the Spanish forces during the siege of Málaga by the Catholic Monarchs against the Emirate of Granada. During the American Civil War vehicles for conveying the wounded off the field of battle were called ambulance wagons.[5] Field hospitals were still called ambulances during the Franco-Prussian War[6] of 1870 and in the Serbo-Turkish war of 1876[7] even though the wagons were first referred to as ambulances about 1854 during the Crimean War.[8]

History

The history of the ambulance begins in ancient times, with the use of carts to transport incurable patients by force. Ambulances were first used for emergency transport in 1487 by the Spanish, and civilian variants were put into operation during the 1830s.[9] Advances in technology throughout the 19th and 20th centuries led to the modern self-powered ambulances.

Functional types

Ambulances can be grouped into types depending on whether or not they transport patients, and under what conditions. In some cases, ambulances may fulfill more than one function (such as combining emergency ambulance care with patient transport:

- Emergency ambulance – The most common type of ambulance, which provides care to patients with an acute illness or injury. These can be road-going vans, boats, helicopters, fixed-wing aircraft (known as air ambulances), or even converted vehicles such as golf carts.

- Patient transport ambulance – A vehicle, which has the job of transporting patients to, from or between places of medical treatment, such as hospital or dialysis center, for non-urgent care. These can be vans, buses, or other vehicles.

- Response vehicle – Also known as a fly-car, nontransporting EMS vehicle and variations. A vehicle that is used to reach an acutely ill patient quickly, and provide on-scene care. In some places, these vehicles can transport a patient, but only if they are able to sit in a regular car seat. Response units may be backed up by an emergency ambulance that can transport the patient or may deal with the problem on scene, with no requirement for a transport ambulance. These can be a wide variety of vehicles, from standard cars to modified vans, motorcycles, pedal cycles, quad bikes or horses. Fire engines are often used for this purpose in North America. These units can function as a vehicle for officers or supervisors (similar to a fire chief's vehicle, but for ambulance services).

- Charity ambulance – A special type of patient transport ambulance is provided by a charity for the purpose of taking sick children or adults on trips or vacations away from hospitals, hospices, or care homes where they are in long-term care. Examples include the United Kingdom's 'Jumbulance' project.[10] These are usually based on a bus.

- Bariatric ambulance – A special type of patient transport ambulance designed for extremely obese patients equipped with the appropriate tools to move and manage these patients.

- Rapid organ recovery ambulance collects the bodies of people who have died suddenly from heart attacks, accidents and other emergencies and try to preserve their organs."[11][12] New York City is launching a pilot program deploying one such ambulance with a $1.5 million, three-year grant.[11]

Vehicle types

In the US, there are four types of ambulances. There are Type I, Type II, Type III, and Type IV. Type I is based upon a heavy truck chassis with a custom rear compartment that is often referred to as a "box." Type I ambulances are primarily used for Advanced Life Support(ALS), also referred to as Mobile Intensive Care Unit(MICU) in some jurisdictions, and rescue work. A Type II ambulance is based on a commercial heavy-duty van with few modifications except for a raised roof and a secondary air conditioning unit for the rear of the vehicle. These types of ambulances are primarily used for Basic Life Support(BLS) and transfer of patients but it is not uncommon to find them used for advanced life support and rescue. Type III is a van chassis but with a custom-made rear compartment and has the same uses as Type I ambulances. Type IV is for smaller ad hoc patient transfer that use smaller utility vehicles in which passenger vehicles and trucks would have difficulty in traversing, such as large industrial complexes, commercial venues, and special events with large crowds; they generally do not fall under Federal Regulations.[13][14][15]

Ambulances can be based on many types of vehicle although emergency and disaster conditions may lead to other vehicles serving as makeshift ambulances:

A modern American ambulance built on the chassis of a Ford F-450 truck, with extensive external storage

A modern American ambulance built on the chassis of a Ford F-450 truck, with extensive external storage

Van or pickup truck – A typical general-purpose ambulance is based on either the chassis of a van (vanbulance) or a light-duty truck. This chassis is then modified to the designs and specifications of the purchaser. Vans may either retain their original body and be upfitted inside, or may be based on a chassis without the original body with a modular box body fitted instead. Those based on pickup trucks almost always have modular bodies. Those vehicles intended for especially intensive care or require a large amount of equipment to be carried may be based on medium-duty trucks.

- Car – Used either as a fly-car for rapid response[2] or to transport patients who can sit, these are standard car models adapted to the requirements of the service using them. Some cars are capable of taking a stretcher with a recumbent patient, but this often requires the removal of the front passenger seat, or the use of a particularly long car. This was often the case with early ambulances, which were converted (or even serving) hearses, as these were some of the few vehicles able to accept a human body in a supine position. Some operators use modular-body transport ambulances based on the chassis of a minivan and station wagon.

- Motorcycle and motor scooter – In urban areas, these may be used for rapid response in an emergency[16] as they can travel through heavy traffic much faster than a car or van. Trailers or sidecars can make these patient transporting units.[17][18] See also motorcycle ambulance.

- Bicycle – Used for response, but usually in pedestrian-only areas where large vehicles find access difficult.[19][20] Like the motorcycle ambulance, a bicycle may be connected to a trailer for patient transport, most often in the developing world.[21] See also cycle responder.

- All-terrain vehicle (ATV) – for example quad bikes; these are used for response off-road,[22] especially at events. ATVs can be modified to carry a stretcher, and are used for tasks such as mountain rescue in inaccessible areas.

- Golf cart or Neighborhood Electric Vehicle – Used for rapid response at events[23] or on campuses. These function similarly to ATVs, with less rough terrain capability, but with less noise.

- Helicopter – Usually used for emergency care, either in places inaccessible by road, or in areas where speed is of the essence, as they are able to travel significantly faster than a road ambulance.[24] Helicopter and fixed-wing ambulances are discussed in greater detail at air ambulance.

- Fixed-wing aircraft – These can be used for either acute emergency care in remote areas (such as in Australia, with the 'Flying Doctors'[25]), for patient transport over long distances (e.g. a re-patriation following an illness or injury in a foreign country[26]), or transportation between distant hospitals. Helicopter and fixed-wing ambulances are discussed in greater detail at air ambulance.

- Boat – Boats can be used to serve as ambulances, especially in island areas[27] or in areas with a large number of canals, such as the Venetian water ambulances. Some lifeboats or lifeguard vessels may fit the description of an ambulance as they are used to transport a casualty.

- Bus – In some cases, buses can be used for multiple casualty transport, either for the purposes of taking patients on journeys,[10] in the context of major incidents, or to deal with specific problems such as drunken patients in town centres.[28][29] Ambulance buses are discussed at greater length in their own article.

- Trailer – In some instances a trailer, which can be towed behind a self-propelled vehicle can be used. This permits flexibility in areas with minimal access to vehicles, such as on small islands.[30]

- Horse and cart – Especially in developing world areas, more traditional methods of transport include transport such as horse and cart, used in much the same way as motorcycle or bicycle stretcher units to transport to a local clinic.

- Fire engine – Fire services (especially in North America) often train firefighters to respond to medical emergencies and most apparatuses carry at least basic medical supplies. By design, most apparatuses cannot transport patients unless they can sit in the cab.

Vehicle type gallery

Ambulance in Switzerland

Ambulance in Switzerland.jpg) New York City Fire Department

New York City Fire Department Ford Econoline van-body Ambulance in Philippines

Ford Econoline van-body Ambulance in Philippines Audi A4 Avant fly-car in Germany

Audi A4 Avant fly-car in Germany An EMT's scooter in Israel

An EMT's scooter in Israel In large, congested cities, paramedics may travel by bicycle, such as this one of the London Ambulance Service

In large, congested cities, paramedics may travel by bicycle, such as this one of the London Ambulance Service An air ambulance in Austria

An air ambulance in Austria_Pilatus_PC-12-45_at_Wagga_Wagga_Airport.jpg) An air ambulance in Australia

An air ambulance in Australia A water ambulance in the Scilly Isles

A water ambulance in the Scilly Isles

A Russian hospital train

A Russian hospital train- Ambulance bus

Design and construction

Ambulance design must take into account local conditions and infrastructure. Maintained roads are necessary for road-going ambulances to arrive on scene and then transport the patient to a hospital, though in rugged areas four-wheel drive or all-terrain vehicles can be used. Fuel must be available and service facilities are necessary to maintain the vehicle.

Methods of summoning (e.g. telephone) and dispatching ambulances usually rely on electronic equipment, which itself often relies on an intact power grid. Similarly, modern ambulances are equipped with two-way radios[31] or cellular telephones to enable them to contact hospitals, either to notify the appropriate hospital of the ambulance's pending arrival, or, in cases where physicians do not form part of the ambulance's crew, to confer with a physician for medical oversight.[32]

Ambulances often have two manufacturers. The first is frequently a manufacturer of light or medium trucks or full-size vans (or in some places, cars) such as Mercedes-Benz, Nissan, Toyota, or Ford.[33] The second manufacturer (known as second stage manufacturer) purchases the vehicle (which is sometimes purchased incomplete, having no body or interior behind the driver's seat) and turns it into an ambulance by adding bodywork, emergency vehicle equipment, and interior fittings. This is done by one of two methods – either coachbuilding, where the modifications are started from scratch and built on to the vehicle, or using a modular system, where a pre-built 'box' is put on to the empty chassis of the ambulance, and then finished off.

Modern ambulances are typically powered by internal combustion engines, which can be powered by any conventional fuel, including diesel, gasoline or liquefied petroleum gas,[34][35] depending on the preference of the operator and the availability of different options. Colder regions often use gasoline-powered engines, as diesels can be difficult to start when they are cold. Warmer regions may favor diesel engines, as they are more efficient and more durable. Diesel power is sometimes chosen due to safety concerns, after a series of fires involving gasoline-powered ambulances during the 1980s. These fires were ultimately attributed in part to gasoline's higher volatility in comparison to diesel fuel.[36][37] The type of engine may be determined by the manufacturer: in the past two decades, Ford[38][39][40] would only sell vehicles for ambulance conversion if they are diesel-powered. Beginning in 2010, Ford will sell its ambulance chassis with a gasoline engine in order to meet emissions requirements.[41]

Standards

Many regions have prescribed standards which ambulances should, or must, meet in order to be used for their role. These standards may have different levels which reflect the type of patient which the ambulance is expected to transport (for instance specifying a different standard for routine patient transport than high dependency), or may base standards on the size of vehicle.

For instance, in Europe, the European Committee for Standardization publishes the standard CEN 1789, which specifies minimum compliance levels across the build of ambulance, including crash resistance, equipment levels, and exterior marking. In the United States, standards for ambulance design have existed since 1976, where the standard is published by the General Services Administration and known as KKK-1822-A.[42] This standard has been revised several times, and is currently in version 'F' change #10, known as KKK-A-1822F, although not all states have adopted this version. The National Fire Protection Association has also published a design standard, NFPA 1917, which some administrations are considering switching to if KKK-A-1822F is withdrawn.[43] The Commission on Accreditation of Ambulance Services (CAAS) has published its Ground Vehicle Standard for Ambulances effective July 2016. This standard is similar to the KKK-A-1822F and NFPA 1917–2016 specifications.

The move towards standardisation is now reaching countries without a history of prescriptive codes, such as India, which approved its first national standard for ambulance construction in 2013.[44]

Safety

Ambulances, like other emergency vehicles, are required to operate in most weather conditions, including those during which civilian drivers often elect to stay off the road. Also, the ambulance crew's responsibilities to their patient often preclude their use of safety devices such as seat belts. Research has shown that ambulances are more likely to be involved in motor vehicle collisions resulting in injury or death than either fire trucks or police cars. Unrestrained occupants, particularly those riding in the patient-care compartment, are particularly vulnerable.[45] When compared to civilian vehicles of similar size, one study found that on a per-accident basis, ambulance collisions tend to involve more people, and result in more injuries.[46] An 11-year retrospective study concluded in 2001 found that although most fatal ambulance crashes in the United States occurred during emergency runs, they typically occurred on improved, straight, dry roads, during clear weather.[47] Furthermore, paramedics are also at risk in ambulances while helping patients, as 27 paramedics died during ambulance trips in the US between 1991 and 2006.[48]

Equipment

In addition to the equipment directly used for the treatment of patients, ambulances may be fitted with a range of additional equipment which is used in order to facilitate patient care. This could include:

- Two-way radio – One of the most important pieces of equipment in modern emergency medical services as it allows for the issuing of jobs to the ambulance, and can allow the crew to pass information back to control or to the hospital (for example a priority ASHICE message to alert the hospital of the impending arrival of a critical patient.)[31][32] More recently many services worldwide have moved from traditional analog UHF/VHF sets, which can be monitored externally, to more secure digital systems, such as those working on a GSM system, such as TETRA.[49]

- Mobile data terminal – Some ambulances are fitted with Mobile data terminals (or MDTs), which are connected wirelessly to a central computer, usually at the control center. These terminals can function instead of or alongside the two-way radio and can be used to pass details of jobs to the crew, and can log the time the crew was mobile to a patient, arrived, and left the scene, or fulfill any other computer-based function.[50]

- Evidence gathering CCTV – Some ambulances are now being fitted with video cameras used to record activity either inside or outside the vehicle. They may also be fitted with sound recording facilities. This can be used as a form of protection from violence against ambulance crews,[51] or in some cases (dependent on local laws) to prove or disprove cases where a member of the crew stands accused of malpractice.

- Tail lift or ramp – Ambulances can be fitted with a tail lift or ramp in order to facilitate loading a patient without having to undertake any lifting. This is especially important where the patient is obese or specialty care transports that require large, bulky equipment such as a neonatal incubator or hospital beds. There may also be equipment linked to this such as winches which are designed to pull heavy patients into the vehicle.[52]

- Trauma lighting – In addition to normal working lighting, ambulances can be fitted with special lighting (often blue or red) which is used when the patient becomes photosensitive.

- Air conditioning – Ambulances are often fitted with a separate air conditioning system to serve the working area from that which serves the cab. This helps to maintain an appropriate temperature for any patients being treated but may also feature additional features such as filtering against airborne pathogens.

- Data recorders – These are often placed in ambulances to record such information as speed, braking power and time, activation of active emergency warnings such as lights and sirens, as well as seat belt usage. These are often used in coordination with GPS units.[53]

Intermediate technology

In parts of the world that lack a high level of infrastructure, ambulances are designed to meet local conditions, being built using intermediate technology. Ambulances can also be trailers, which are pulled by bicycles, motorcycles, tractors, or animals. Animal-powered ambulances can be particularly useful in regions that are subject to flooding. Motorcycles fitted with sidecars (or motorcycle ambulances) are also used, though they are subject to some of the same limitations as more traditional over-the-road ambulances. The level of care provided by these ambulances varies between merely providing transport to a medical clinic to providing on-scene and continuing care during transport.[17]

The design of intermediate technology ambulances must take into account not only the operation and maintenance of the ambulance, but its construction as well. The robustness of the design becomes more important, as does the nature of the skills required to properly operate the vehicle. Cost-effectiveness can be a high priority.[18][54]

Appearance and markings

Emergency ambulances are highly likely to be involved in hazardous situations, including incidents such as a road traffic collision, as these emergencies create people who are likely to be in need of treatment. They are required to gain access to patients as quickly as possible, and in many countries, are given dispensation from obeying certain traffic laws. For instance, they may be able to treat a red traffic light or stop sign as a yield sign ('give way'),[55] or be permitted to break the speed limit.[56] Generally, the priority of the response to the call will be assigned by the dispatcher, but the priority of the return will be decided by the ambulance crew based on the severity of the patient's illness or injury. Patients in significant danger to life and limb (as determined by triage) require urgent treatment by advanced medical personnel,[57] and because of this need, emergency ambulances are often fitted with passive and active visual and/or audible warnings to alert road users.

Passive visual warnings

Top: The Star of Life, the Red Cross, the Red Crescent

Bottom: The Maltese Cross, Battenburg markings

The passive visual warnings are usually part of the design of the vehicle, and involve the use of high contrast patterns. Older ambulances (and those in developing countries) are more likely to have their pattern painted on, whereas modern ambulances generally carry retro-reflective designs, which reflects light from car headlights or torches. Popular patterns include 'checker board' (alternate coloured squares, sometimes called 'Battenburg', named after a type of cake), chevrons (arrowheads – often pointed towards the front of the vehicle if on the side, or pointing vertically upwards on the rear) or stripes along the side (these were the first type of retro-reflective device introduced, as the original reflective material, invented by 3M, only came in tape form). In addition to retro-reflective markings, some services now have the vehicles painted in a bright (sometimes fluorescent) yellow or orange for maximum visual impact, though classic white or red are also common. Fire department-operated ambulances are often painted red to match the fire apparatuses.

Another passive marking form is the word ambulance (or local language variant) spelled out in reverse on the front of the vehicle. This enables drivers of other vehicles to more easily identify an approaching ambulance in their rear view mirrors. Ambulances may display the name of their owner or operator, and an emergency telephone number for the ambulance service.

Ambulances may also carry an emblem (either as part of the passive warning markings or not), such as a Red Cross, Red Crescent or Red Crystal (collective known as the Protective Symbols). These are symbols laid down by the Geneva Convention, and all countries signatory to it agree to restrict their use to either (1) Military Ambulances or (2) the national Red Cross or Red Crescent society. Use by any other person, organization or agency is in breach of international law. The protective symbols are designed to indicate to all people (especially combatants in the case of war) that the vehicle is neutral and is not to be fired upon, hence giving protection to the medics and their casualties, although this has not always been adhered to.[58] In Israel, Magen David Adom, the Red Cross member organization use a red Star of David, but this does not have recognition beyond Israeli borders, where they must use the Red Crystal.

The Star of Life is widely used, and was originally designed and governed by the U.S. National Highway Traffic Safety Administration,[59] because the Red Cross symbol is legally protected by both National[60] and international[61][62] law.

Ambulance services that have historical origins such as the Order of St John, the Order of Malta Ambulance Corps[63] and Malteser International[64] often use the Maltese cross to identify their ambulances. This is especially important in countries such as Australia, where St. John Ambulance operate one state and one territory ambulance service, and all of Australia's other ambulance services use variations on a red Maltese cross.[65][66][67][68]

Fire service operated ambulances may display the Cross of St. Florian (often incorrectly called a Maltese cross) as this cross is frequently used as a fire department logo (St. Florian being the patron saint of firefighters).[69]

Active visual warnings

The active visual warnings are usually in the form of flashing lights. These flash in order to attract the attention of other road users as the ambulance approaches, or to provide warning to motorists approaching a stopped ambulance in a dangerous position on the road. Common colours for ambulance warning beacons are blue, red, amber, and white (clear). However the colours may vary by country and sometimes by operator.

There are several technologies in use to achieve the flashing effect. These include flashing a light bulb or LED, flashing or rotating halogen, and strobe lights, which are usually brighter than incandescent lights. Each of these can be programmed to flash singly or in groups, and can be programmed to flash in patterns (such as a left -> right pattern for use when the ambulance is parked on the left hand side of the road, indicating to other road users that they should move to the right (away from the ambulance)). Incandescent and LED lights may also be programmed to burn steadily, without flashing, which is required in some provinces.

Emergency lights may simply be mounted directly on the body, or may be housed in special fittings, such as in a lightbar or in special flush-mount designs (as seen on the Danish ambulance to the right), or may be hidden in a host light (such as a headlamp) by drilling a hole in the host light's reflector and inserting the emergency light. These hidden lights may not be apparent until they are activated. Additionally, some of the standard lights fitted to an ambulance (e.g. headlamps, tail lamps) may be programmed to flash. Flashing headlights (typically the high beams, flashed alternately) are known as a wig-wag. Additional white lights may be placed strategically around the vehicle to illuminate the area around it when it is dark, almost always at the rear for loading and unloading stretchers and often at the sides as well. In areas very far North or South where there are times of year with long periods of darkness, additional driving lights at the front are often fitted as well to increase visibility for the driver.

In order to increase safety, it is best practice to have 360° coverage with the active warnings, improving the chance of the vehicle being seen from all sides. In some countries, such as the United States, this may be mandatory. The roof, front grille, sides and rear of the body, and front fenders are common places to mount emergency lights. A certain balance must be made when deciding on the number and location of lights: too few and the ambulance may not be noticed easily, too many and it becomes a massive distraction for other road users more than it is already, increasing the risk of local accidents.

See also Emergency vehicle equipment.

Audible warnings

In addition to visual warnings, ambulances can be fitted with audible warnings, sometimes known as sirens, which can alert people and vehicles to the presence of an ambulance before they can be seen. The first audible warnings were mechanical bells, mounted to either the front or roof of the ambulance. Most modern ambulances are now fitted with electronic sirens, producing a range of different noises which ambulance operators can use to attract more attention to themselves, particularly when proceeding through an intersection or in heavy traffic.[70]

The speakers for modern sirens can be integral to the lightbar, or they may be hidden in or flush to the grill to reduce noise inside the ambulance that may interfere with patient care and radio communications. Ambulances can additionally be fitted with airhorn audible warnings to augment the effectiveness of the siren system, or may be fitted with extremely loud two-tone air horns as their primary siren.

A recent development is the use of the RDS system of car radios. The ambulance is fitted with a short range FM transmitter, set to RDS code 31, which interrupts the radio of all cars within range, in the manner of a traffic broadcast, but in such a way that the user of the receiving radio is unable to opt-out of the message (as with traffic broadcasts).[71] This feature is built into every RDS radio for use in national emergency broadcast systems, but short-range units on emergency vehicles can prove an effective means of alerting traffic to their presence. It is, however, unlikely that this system could replace audible warnings, as it is unable to alert pedestrians, those not using a compatible radio or even have it turned off.[72]

Costs

_313_CDI_MWB_van%2C_St_John_Ambulance_(2017-12-09).jpg)

The cost of an ambulance ride may be paid for from several sources, and this will depend on the local situation type of service being provided, by whom, and to whom.

- Government-funded service – The full or the majority of the cost of transport by ambulance is borne by the local, regional, or national government (through their normal taxation).[73]

- Privately funded service – Transport by ambulance is paid for by the patient themselves, or through their insurance company. This may be at the point of care (i.e. payment or guarantee must be made before treatment or transport), although this may be an issue with critically injured patients, unable to provide such details, or via a system of billing later on.[74]

- Charity-funded service – Transport by ambulance may be provided free of charge to patients by a charity, although donations may be sought for services received.[75]

- Hospital-funded service – Hospitals may provide the ambulance transport free of charge, on the condition that patients use the hospital's services (which they may have to pay for).[76]

Crewing

There are differing levels of qualification that the ambulance crew may hold, from holding no formal qualification to having a fully qualified doctor on board. Most ambulance services require at least two crew members to be on every ambulance (one to drive, and one to attend the patient). It may be the case that only the attendant need be qualified, and the driver might have no medical training. In some locations, an advanced life support ambulance may be crewed by one paramedic and one technician.

Common ambulance crew qualifications are:

- First responder – A person who arrives first at the scene of an incident,[77] and whose job is to provide early critical care such as cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) or using an automated external defibrillator (AED). First responders may be dispatched by the ambulance service, may be passers-by, or may be dispatched to the scene from other agencies, such as the police or fire departments. They may be on duty for another agency, or volunteers who are on-call during their free time.

- Ambulance driver – Some services employ staff with no medical qualification (or just basic first aid training) whose job is to simply drive the vehicle. In some emergency ambulance contexts this term is a pejorative towards personnel with higher medical training, as it implies they perform no function other than driving, although it may be acceptable for patient transport or community operations. Ambulance drivers may also have training in using the radio and knowing where medical supplies are stored in the ambulance.

- Non-emergency driver/attendant – This role has different levels of training across the world, but these staff are usually only required to perform patient transport duties (which can include stretcher or wheelchair cases), rather than acute care.[78] Dependent on provider, they may be trained in first aid or extended skills such as use of an AED, oxygen therapy and other lifesaving or palliative skills. They may provide emergency cover when other units are not available, or when accompanied by a fully qualified technician or paramedic.

- Emergency care assistant/Emergency care support worker (ECA/ECSW) – Members of a frontline ambulance that drive the vehicles under both emergency and non-emergency conditions to incidents. Their role is to assist the clinician that they are working with, either a Technician or Paramedic, in their duties, whether that be drawing up drugs, setting up fluids (but not attaching), doing basic observations or performing 12 lead ECG assessments.

- Emergency medical technician (EMT) – Also known as an Ambulance Technician. Technicians are usually able to perform a wide range of emergency care skills, such as defibrillation, spinal immobilization, bleeding control, splinting of suspected fractures, assisting the patient with certain medications, and oxygen therapy. Some countries split this term into levels (such as in the US, where there is EMT-Basic and EMT-Intermediate).[79]

- Registered nurse (RN) – In some systems, nurses are the primary providers of advanced-level care on ambulances, often in place of paramedics. This includes Estonia, the Netherlands,[80] Sweden[81] and Spain.[82] Nurses may also work on ambulances for critical care transport.

- Paramedic – This is a high level of medical training and usually involves key skills not permissible for technicians, such as cannulation (and with it the ability to administer a range of drugs such as morphine), tracheal intubation and other skills such as performing a cricothyrotomy.[83] Dependent on jurisdiction, the title "paramedic" can be a protected title, and use of it without the relevant qualification may result in criminal prosecution.[84]

- Emergency Care Practitioner – This position is designed to bridge the link between ambulance care and the care of a general practitioner. ECPs are already qualified paramedics who have undergone further training,[85] and are trained to prescribe medicines for longer-term care, such as antibiotics, as well as being trained in a range of additional diagnostic techniques.

- Physician Assistant – Physician Assistants are found predominately in English-speaking countries and may also be known as physician associates in some countries. PA's mirror the practice of a physician and are capable of providing the range of medical skills a physician provides. They generally work in collaboration with a physician, although in an ambulance environment this may not be possible. Instead, advanced directives or electronic communication is available to PA's to consult with physicians when required.

- Physician – In some systems such as the SAMU in France, it is common for doctors to staff ambulances. On the other hand, this is rare in systems that rely heavily on paramedics or field nurses. In those cases, doctors may be present in specialist ambulance units – most notably the air ambulances.[86][87]

Military use

Military ambulances have historically included vehicles based on civilian designs and at times also included armored, but unarmed, vehicle ambulances based upon armoured personnel carriers (APCs). In the Second World War vehicles such as the Hanomag Sd Kfz 251 half-track were pressed into service as ad hoc ambulances, and in more recent times purpose-built AFVs such as the U.S. M1133 Medical Evacuation Vehicle serve the exclusive purpose of armored medical vehicles. Civilian based designs may be painted in appropriate colors, depending on the operational requirements (i.e. camouflage for field use, white for United Nations peacekeeping, etc.). For example, the British Royal Army Medical Corps has a fleet of white ambulances, based on production trucks. Military helicopters have also served both as ad hoc and purpose-built air ambulances since they are extremely useful for MEDEVAC.[88] In terms of equipment, military ambulances are barebones, often being nothing more than a box on wheels with racks to place manual stretchers, though for the operational conditions and level of care involved this is usually sufficient.

Since laws of war demand ambulances be marked with one of the Emblems of the Red Cross not to mount offensive weapons, military ambulances are often unarmed.[89] It is a generally accepted practice in most countries to classify the personnel attached to military vehicles marked as ambulances as non-combatants; however, this does not always exempt medical personnel from coming under fire—accidental or deliberate. As a result, medics and other medical personnel attached to military ambulances are usually put through basic military training,[90] on the assumption that they may have to use a weapon. The laws of war do allow non-combatant military personnel to carry individual weapons for protecting themselves and casualties. However, not all militaries exercise this right to their personnel.

Recently, the Israeli Defense Forces has modified a number of its Merkava main battle tanks with ambulance features in order to allow rescue operations to take place under heavy fire in urban warfare.[91] The modifications were made following a failed rescue attempt in which Palestinian gunmen killed two soldiers who were providing aid for a Palestinian woman in Rafah.[92] Since M-113 armored personnel carriers and regular up-armored ambulances are not sufficiently protected against anti-tank weapons and improvised explosive devices,[93] it was decided to use the heavily armored Merkava tank. Its rear door enables the evacuation of critically wounded soldiers. Israel did not remove the Merkava's weaponry, claiming that weapons were more effective protection than emblems since Palestinian militants would disregard any symbols of protection and fire at ambulances anyway. For use as ground ambulances and treatment & evacuation vehicles, the United States military currently employs the M113, the M577, the M1133 Stryker Medical Evacuation Vehicle (MEV), and the RG-33 Heavily Armored Ground Ambulance (HAGA) as treatment and evacuation vehicles, with contracts to incorporate the newly designed M2A0 Armored Medical Evacuation Vehicle (AMEV), a variant of the M2 Bradley Fighting Vehicle (formerly known as the ATTV).[94][95][96]

Some navies operate ocean-going hospital ships to lend medical assistance in high casualty situations like wars or natural disasters.[97] These hospital ships fulfill the criteria of an ambulance (transporting the sick or injured), although the capabilities of a hospital ship are more on par with a Mobile Army Surgical Hospital. In line with the laws of war, these ships can display a prominent Red Cross or Red Crescent to confer protection under the appropriate Geneva Convention. However, this designation has not always protected hospital ships from enemy fire.[98]

Ambulette

Ambulettes provide patient transport service for non-emergency situations. Scheduling is a major factor in their effective use.[99]

Reuse of retired ambulances

When an ambulance is retired, it may be donated or sold to another EMS provider.[100][101] Alternately, it may be adapted into a storage and transport vehicle for crime scene identification equipment, a command post at community events, or support vehicle, such as a logistics unit.[102] Others are refurbished and resold,[103] or may just have their emergency equipment removed to be sold to private businesses or individuals, who then can use them as small recreational vehicles. They may also have a perfectly serviceable body or vehicle (or both) separated from the other and reused.

Toronto City Council has begun a "Caravan of Hope" project to provide retired Toronto ambulances a second life by donating them to the people of El Salvador. Since laws in Ontario require ambulances to be retired after just four and a half years in service, the City of Toronto decommissions and auctions 28 ambulances each year.[104]

See also

References and notes

- Skinner, Henry Alan. 1949, "The Origin of Medical Terms". Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins

- "Essex Ambulance Response Cars". Car Pages. 24 July 2004. Retrieved 27 June 2007.

- "How Products Are Made: Ambulance". How products are made. Archived from the original on 25 March 2007. Retrieved 2 June 2007.

- Oxford English Dictionary ambulance definition 1

- "Civil War Ambulance Wagons". civilwarhome.com.

- The memoirs of Charles E. Ryan With An Ambulance Personal Experiences And Adventures With Both Armies 1870–1871 Archived 1 April 2016 at the Wayback Machine and of Emma Maria Pearson and Louisa McLaughlin Our Adventures During the War of 1870 "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 April 2008. Retrieved 25 March 2008.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Emma Maria Pearson and Louisa McLaughlin Service in Servia Under the Red Cross "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 July 2008. Retrieved 7 February 2016.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Oxford English Dictionary ambulance definition 2a

- Katherine T. Barkley (1990). The Ambulance. Exposition Press.

- "Questions and Answers". Jumbulance Travel Trust. Archived from the original on 2 July 2007. Retrieved 2 June 2007.

- Stein, Rob (24 May 2008). "N.Y. Planning Special Ambulance To Recover Organs". The Washington Post.

- Saletan, William (27 March 2008). "Meat Wagons". Slate.

- "Index of Federal Specifications, Standards, and Commercial Item Descriptions". gsa.gov.

- "Ambulances – Type I, Type II, Type III and Type IV Ambulances". metronixinc.com.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 4 November 2014. Retrieved 17 December 2013.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "South Central Ambulance Service NHS Trust – About Us". South Central Ambulance Service NHS Trust. Archived from the original on 3 March 2009. Retrieved 18 October 2009.

- "News Reference to Motorcycle Trailer Ambulance". TNN. Archived from the original on 27 September 2007. Retrieved 2 June 2007.

- "Motorcycle Trailer-Ambulance Brochure" (PDF). IT Transport LTD. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 June 2007. Retrieved 2 June 2007.

- "Two-wheeled medics cover more ground in the capital". Archived from the original on 27 April 2011. Retrieved 18 October 2009.

- "Square-Mile cycle paramedics become the new City-Slickers". Archived from the original on 27 April 2011. Retrieved 18 October 2009.

- "Bike Ambulance Project". Design for Development. 20 July 2005. Archived from the original on 28 September 2007. Retrieved 14 July 2007.

- "Information on Quadtech EMS quad". Quadtech. Retrieved 2 June 2007.

- "EMS golf cart brochure". Diversified Golf Cars. Archived from the original on 5 April 2007. Retrieved 2 June 2007.

- "Highways Agency – Air Ambulance". Archived from the original on 3 June 2009. Retrieved 18 October 2009.

- "Royal Flying Doctor Service of Australia". Royal Flying Doctor Service of Australia. Archived from the original on 12 June 2007. Retrieved 2 June 2007.

- "Heathrow Air Ambulance Service". Heathrow air ambulance. Archived from the original on 17 June 2007. Retrieved 2 June 2007.

- "Islanders to get Ambulance Boat". BBC. 10 October 2003. Retrieved 18 October 2009.

- "Ambulance crews prepare for party night pressure". London Ambulance Service. 18 December 2008. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016.

- "Aboard the 'Booze Bus'". BBC News. 17 December 2007. Retrieved 1 January 2010.

- "General Information – Medical Services". Isle of Sark Government. Archived from the original on 17 February 2012.

- "Handheld radios for Emergency Ambulance Service". Emergency Ambulance.com. 16 January 2003. Archived from the original on 27 September 2007. Retrieved 28 June 2007.

- "New technology closes gap between accident victims and ER". CNN News. 7 April 1999. Retrieved 27 June 2007.

- "Mystere – Chassis". Demers Ambulances. Archived from the original on 19 June 2007. Retrieved 18 October 2009.

- "The Royal Air Force Motor Sports Association utilizes an LPG-powered ambulance". RAFMSA. 24 November 2005. Archived from the original on 1 July 2007. Retrieved 2 June 2007.

- "The United States Air Force lists an LPG-powered ambulance on a 2001 vehicle roster". 13 November 2001. Archived from the original (DOC) on 14 June 2007. Retrieved 2 June 2007.

- "National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, see campaign ID #s 87V111000 & 87V113000". NHTSA. Archived from the original on 30 May 2007. Retrieved 2 June 2007.

- "Ford Ambulance/Van Fuel-Fed Fires". Center for Auto Safety. Retrieved 13 February 2010.

- "2006 Ford E-Series Cutaway Chassis: Specifications". Ford. Retrieved 2 June 2007.

- "2006 Ford F-Series Super Duty Chassis Cab Ambulance: Specifications". Ford. Retrieved 2 June 2007.

- "2006 Ford E-Series Van Ambulance: Specifications". Ford. Retrieved 2 June 2007.

- James Philips. "Ford to Offer Gasoline Ambulances in 2010".

- Vogt F (1976). "Equipment: Federal Specification, Ambulance KKK-A-1822". Emerg Med Serv. 5 (3): 58, 60–4. PMID 1028572.

- Cole, Dean (2013). "Ambulance Vehicle Design Specifications Revision" (PDF). Nebraska EMS/Trauma Program. Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 April 2015. Retrieved 24 May 2013.

- "Ministry gives its nod to national ambulance code". The Statesman. 7 June 2013. Archived from the original on 20 June 2013.

- Becker LR, Zaloshnja E, Levick N, Li G, Miller TR (November 2003). "Relative risk of injury and death in ambulances and other emergency vehicles". Accid Anal Prev. 35 (6): 941–8. doi:10.1016/S0001-4575(02)00102-1. PMID 12971929.

- Ray AF, Kupas DF (October–December 2005). "Comparison of crashes involving ambulances with those of similar-sized vehicles". Prehosp Emerg Care. 9 (4): 412–5. doi:10.1080/10903120500253813. PMID 16263674. S2CID 22922599.

- Kahn CA, Pirrallo RG, Kuhn EM (July 2001). "Characteristics of fatal ambulance crashes in the United States: an 11-year retrospective analysis". Prehosp Emerg Care. 5 (3): 261–9. doi:10.1080/10903120190939751. PMID 11446540. S2CID 24097668.

- "New Ambulance Design Protects Paramedics". WESH News. Archived from the original on 14 November 2013. Retrieved 17 October 2009.

- "Motorola and Tetra Ireland Consortium Deliver National Public Safety Network" (PDF). Motorola. Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 September 2012. Retrieved 19 October 2009.

- "MDT Market Sectors". Microbus. Archived from the original on 27 March 2010. Retrieved 13 June 2007.

- "CCTV to protect ambulance staff". BBC News. 26 July 2004. Retrieved 13 June 2007.

- "Ambulance Lifts". Ross and Bonnyman. Archived from the original on 1 July 2007. Retrieved 27 June 2007.

- "Press Releases". Archived from the original on 13 July 2011.

- Hofman, Jan J.; Dzimadzi, Chris; Lungu, Kingsley; Ratsma, Esther Y.; Hussein, Julia (2008). "Motorcycle ambulances for referral of obstetric emergencies in rural Malawi: Do they reduce delay and what do they cost?" (PDF). International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics. International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics. 102 (2): 191–197. doi:10.1016/j.ijgo.2008.04.001. PMID 18555998.

- "Ontario Highway Traffic Act". 2009. pp. Section 144.20. Archived from the original on 22 November 2009. Retrieved 19 November 2009.

- "Ontario Highway Traffic Act". Province of Ontario. pp. Section 128.0.13. Archived from the original on 22 November 2009. Retrieved 19 November 2009.

- "CTAS Category Definitions". Implementation Guidelines for the Canadian ED Triage & Acuity Scale (CTAS). Canadian Association of Emergency Physician. Archived from the original on 21 September 2010. Retrieved 19 November 2009.

- Dromi, Shai M. (2020). Above the fray: The Red Cross and the making of the humanitarian NGO sector. Chicago: Univ. of Chicago Press. pp. 55–56. ISBN 9780226680101.

- "Star of Life DOT HS 808 721". National Highway Safety Administration. Retrieved 19 November 2009.

- "The Red Cross Emblem". The Canadian Red Cross. Archived from the original on 11 January 2010. Retrieved 19 November 2009.

- "The History of the Emblems". International Committee of the Red Cross. Retrieved 19 November 2009.

- "The Geneva Convention of 1949". International Committee of the Red Cross. Archived from the original on 22 November 2009. Retrieved 19 November 2009.

- "Order of Malta Charity Ireland – Volunteers and Governance – First Aid Course – Ambulance Cover".

- "404". malteser.de. Archived from the original on 8 February 2011.

- "About Queensland Ambulance Service". Archived from the original on 6 July 2007. Retrieved 27 June 2007.

- "ACT Ambulance Service". Archived from the original on 30 June 2007. Retrieved 27 June 2007.

- "Ambulance Service of New South Wales". Archived from the original on 7 June 2007. Retrieved 27 June 2007.

- "South Australian Ambulance Service". Archived from the original on 25 June 2007. Retrieved 27 June 2007.

- "St. Florian – Patron Saint of Firefighters". stflorian.net. Archived from the original on 27 September 2007. Retrieved 3 June 2007.

- "23". Emergency Care Manual. The Canadian Red Cross. Guelph, ON: The StayWell Health Company. 2008. p. 359. ISBN 978-1-58480-404-8.CS1 maint: others (link) Viewed 19 November 2009.

- "Emergency warning device – patent application". Retrieved 19 November 2009.

- Wright, Scott (1997). The Broadcaster's Guide to RDS. Woburn, MA: Butterworth-Heineman. p. 73. ISBN 0-240-80278-0.

- "OHIP:Ambulance Services Billing". Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care. Retrieved 19 November 2009.

- "Payment Policy". American Medical Response. Retrieved 19 November 2009.

- "Yorkshire Air Ambulance Charity". Archived from the original on 25 November 2009. Retrieved 19 November 2009.

- "Ambulance Services". Archived from the original on 25 October 2007. Retrieved 19 November 2009.

- "Role of the First Responder". Resuscitation Council UK. Archived from the original on 29 May 2007. Retrieved 2 June 2007.

- "Ambulance Care Assistant Role". nhs. Archived from the original on 25 November 2009. Retrieved 1 November 2009.

- "US Government Careers advice on EMT". Archived from the original on 7 June 2007. Retrieved 2 June 2007.

- Wulterkens D (6 December 2005). "EMS in the Netherlands: A Dutch Treat?". Journal of Emergency Medical Services.

- Suserud B (2005). "A new profession in the pre-hospital care field: the ambulance nurse". Nursing in Critical Care. 10 (6): 269–71. doi:10.1111/j.1362-1017.2005.00129.x. PMID 16255333.

- "Real Decreto 836/2012, de 25 de mayo, por el que se establecen las características técnicas, el equipamiento sanitario y la dotación de personal de los vehículos de transporte sanitario por carretera" [Royal Decree 836/2012, of 25 May, which establishes the technical characteristics, the sanitary equipment and the staffing of the vehicles of sanitary transport by road]. Boletín Oficial del Estado (in Spanish). 137: 41589–41595. 8 June 2012.

- National Occupational Competency Profile. Paramedic Association of Canada. 2001. pp. 96–97. Retrieved 19 November 2009.

- "UK Health Care Professionals Council advice on use of protected titles". Health care Professionals council. Archived from the original on 7 November 2018. Retrieved 2 June 2007.

- "Definition of an Emergency Care Practitioner". South West Ambulance Service. Archived from the original on 17 May 2007. Retrieved 2 June 2007.

- "London Air Ambulance Crew List". London Air Ambulance. Archived from the original on 8 December 2009. Retrieved 1 November 2009.

- "Surrey Air Ambulance". Surrey Air Ambulance. Archived from the original on 6 October 2009. Retrieved 1 November 2009.

- "History of Military MEDEVAC helicopters". Archived from the original on 17 June 2007. Retrieved 2 June 2007.

- "International Committee of the Red Cross policy on usage". International committee of the Red Cross. Archived from the original on 6 July 2007. Retrieved 2 June 2007.

- "UK Army information on basic training for medical personnel". British Army. Retrieved 1 November 2009.

- "Defense Update page on use of Merkava tank as ambulance". Defense Update. Archived from the original on 27 June 2007. Retrieved 2 June 2007.

- "BBC New article on the killing of soldiers rendering ambulance aid". BBC News. 14 May 2004. Retrieved 2 June 2007.

- "Technical data on armament of M113 APC Ambulance". Inetres. Retrieved 2 June 2007.

- "Armored Medical Evacuation Vehicle AMEV". globalsecurity.org.

- "1-22 Infantry tests ATTV". 1-22infantry.org.

- "Bradley AMEV". Archived from the original on 16 September 2012. Retrieved 6 January 2012.

- "US Navy Military Sealift Command – Hospital Ships". US Navy Military Sealift Command. Archived from the original on 29 June 2007. Retrieved 17 June 2007.

- "Report on the sinking of the HMHS Llandovery Castle". World War One Document Archive. Archived from the original on 14 July 2007. Retrieved 27 June 2007.

- Raymond Hernandez (10 November 1996). "Medicaid Ride Program For Disabled Is Criticized". The New York Times.

- "Report No. 6 of the Community and Health Services, §2: Donation of Decommissioned Ambulances for 2011". Archived from the original on 26 July 2013. Retrieved 4 February 2012. Full report at http://www.york.ca/Regional+Government/Agendas+Minutes+and+Reports/_2011/CHSC+rpt+6.htm Archived 26 July 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- "Media Release: York Region donates ambulance to Haitian recovery efforts". Community and Health Services, York Region. Archived from the original on 26 July 2013. Retrieved 4 February 2012. Archived 7 April 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- "Orangeville Police inherit retired ambulance". Archived from the original on 1 January 2013. Retrieved 7 July 2012.

- "Reconditioned ambulances". Malleyindustries.com.

- "Supporting hope". Retrieved 7 July 2012.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Ambulances. |