Trichomonas tenax

Trichomonas tenax, or oral trichomonas, is a species of Trichomonas commonly found in the oral cavity of humans. Routine hygiene is generally not sufficient to eliminate the parasite, hence its Latin name, meaning "tenacious". The parasite is frequently encountered in periodontal infections, affecting more than 50% of the population in some areas, but it is usually considered insignificant. T. tenax is generally not found on the gums of healthy patients.[2] It is known to play a pathogenic role in necrotizing ulcerative gingivitis and necrotizing ulcerative periodontitis, worsening preexisting periodontal disease.[3] This parasite is also implicated in some chronic lung diseases; in such cases, removal of the parasite is sufficient to allow recovery (Mussaev 1976).

| Trichomonas tenax | |

|---|---|

| |

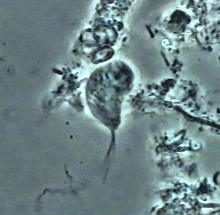

| Parasite taken from the biofilm of a patient with chronic active periodontitis. Phase-contrast microscope, 1000× magnification, salivary smear | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Phylum: | Metamonada |

| Subphylum: | Trichozoa |

| (unranked): | Parabasalia |

| Order: | Trichomonadida |

| Family: | Trichomonadidae |

| Genus: | Trichomonas |

| Species: | T. tenax |

| Binomial name | |

| Trichomonas tenax | |

Morphology

Of the three species in the genus Trichomonas, T. tenax is the smallest, measuring only 5-14 µm long and 6-9 µm wide; specimens can be identified by their long axostyles and tails, 4 anterior flagella, and by the recurrent flagellum that raises an undulating membrane which is two thirds the length of the body. This undulating membrane may appear like small legs. It may occasionally appear larger, allowing it to be confused with Trichomonas vaginalis due to similar morphology. In such cases, the presence of an oral or vaginal parasite should be confirmed, due to the ease with which the parasite can be transmitted through direct contact of mucous membranes.

Life cycle

T. tenax trophozoites survive in the body as mouth scavengers that feed primarily on local microorganisms located between the teeth, tonsillar crypts, pyorrheal pockets, and the gingival margin around the gums. T. tenax trophozoites multiply by longitudinal binary fission. These trophozoites are unable to survive the digestive process.

Clinical

Transmission

T. tenax is a commensal of the human oral cavity, found particularly in the patients with poor oral hygiene and advanced periodontal disease. Transmission is through saliva, droplet spray, and kissing or use of contaminated dishes or drinking water.[4]

Signs and symptoms

T. tenax alone is not known to cause any symptoms. There are merely implications that this parasite may worsen preexisting periodontal disease and in rare cases has been reported to cause bronchopulmonary infections, mainly in patients with underlying cancers or other lung diseases.[4] The organism is believed to enter the respiratory tract by aspiration from the oropharynx.

Mechanism

In infected hosts, the parasite can typically be found among dental calculus, as well as within the tonsillar crypts, which will often become purulent during the course of infection. T. tenax may also be involved in the degradation of periodontal tissue through the secretion of substances such as alkaline phosphatases and the fibronectin cathepsine.[5] T. tenax is classified as a parasite due to the manner in which it causes damage to host tissues; its behavior when in contact with target cells is similar to the closely related and likewise parasitic T. vaginalis.[6] It has no cysts and is only transmitted directly in its vegetative form.

Diagnosis

The specimen of choice for diagnosing Trichomonas tenax trophozoite is mouth scrapings. Microscopic examination of tonsillar crypts and pyorrheal pockets of patients suffering from T. tenax infections often yields the typical trophozoites. Tartar between the teeth and the gingival margin of the gums are the primary areas of the mouth that may also potentially harbor this organism. T. tenax may also be cultured onto appropriate media.

Treatment

Regardless of patient’s demographic characteristics, it seems that oral hygiene instructions in combination with scaling and root planning can help with controlling excessive colonization of parasites, particularly E. gingivalis and T. tenax and their probable opportunistic infestation.[7] T. tenax can easily be detected through the use of phase-contrast microscopy. Biofilm harvested from infested areas of the periodontal pockets can be mounted onto a slide; T. tenax, if present, will be clearly visible. The preparation must use the patient's saliva as the medium, as the use of plain water or saline as hypotonic solutions could cause the cells to lyse.

History

The etymology of the name Trichomonas tenax is from a combination of Greek: trichos (tiny hair) + monas (simple creature), and Latin: tenere (to keep, to stick to).[8]

During the early 1900s, prisoners at the San Quentin prison in California were subject to advanced periodontal disease at a rate of almost 90%, owing at least in part to a high rate of infection by T. tenax.[9] In the Journal of the American Dental Association, it was speculated that this high rate of transmission was attributable to the crowding and poor diets faced by inmates. Age was also an important factor in this population [9] and intense inflammation was observed.

Research directions

Owing to the morphological similarity between T. tenax and other trichomonad spp., examination of a greater number of organisms is necessary to establish a reliable diagnosis than is easily obtained from the patient's mouth. Iin vitro, T. tenax reproduced better in LES medium, pH value between 5.80 and 7.00 with cultivation temperature of 35 °C than other media with pH 5.40 and cultivation temperature of 37 °C.[10] Normal, healthy human saliva is slightly alkaline at pH 7.40. Whitening products have a mean pH of 8.22 with a range (5.09-11.13). Whitening toothpastes have a mean pH of 6.83 with a range (4.22-8.35). Mouthwashes also vary greatly in pH from pH 4.40 to 6.80. Mouth rinsing after an acidic challenge increased salivary pH. The tested mouthwashes raised pH higher than water. Mouthwashes with a neutralizing effect can potentially reduce tooth erosion from acid exposure.[11] Essentially the human mouth is an optimum habitat for this organism and any pH level alteration needed to stunt the reproductive rate significantly would require a duration of time that would cause greater damage to the tooth enamel than to T. tenax. Regular oral hygiene and dental visits to remove dental plaque is currently the best solution to deal with this protozoan.

Other hosts

T. tenax has been found in the mouths of a small proportion of dogs, cats and horses,[12] but other animals are expected to have their own species of Trichomonas .[13]

References

- Dobell, Clifford (6 April 2009). "The common flagellate of the human mouth, (O.F.M.): its discovery and its nomenclature". Parasitology. 31 (1): 138–146. doi:10.1017/S0031182000012671.

- Lyons, T.; Sholten, T.; Palmer, J.C. (October 1980). "Oral amoebiasis: a new approach for the general practitioner in the diagnosis and treatment of periodontal disease". Oral Health. 70 (10): 39–41, 108, 110. PMID 6950337.

- Bonner, M. (2013). To Kiss or Not to Kiss. A cure for gum disease. Amyris Editions. ISBN 978-28755-2016-6.

- Mallat, Hassan; Podglajen, Isabelle; Lavarde, Véronique; Mainardi, Jean-Luc; Frappier, Jérôme; Cornet, Muriel (2004-08-01). "Molecular characterization of Trichomonas tenax causing pulmonary infection". Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 42 (8): 3886–3887. doi:10.1128/JCM.42.8.3886-3887.2004. ISSN 0095-1137. PMC 497589. PMID 15297557.

- Porcheret, H; Maisonneuve, L; Estève, V; Jagot, JL; Le Pennec, MP (February 2002). "Trichomonase pleurale à Trichomonas tenax" [Pleural trichomoniasis due to trichomonas tenax]. Revue des maladies respiratoires (in French). 19 (1): 97–9. PMID 17546821. Retrieved 31 December 2019.

- Ribeiro, L.C.; Santos, C.; Benchimol, M. (May 2015). "Is Trichomonas tenax a parasite or a commensal?". Protist. 166 (2): 196–210. doi:10.1016/j.protis.2015.02.002. PMID 25835639.

- Rashidi Maybodi, Fahimeh; Haerian Ardakani, Ahmad; Fattahi Bafghi, Ali; Haerian Ardakani, Alireza; Zafarbakhsh, Akram (September 2016). "The Effect of Nonsurgical Periodontal Therapy on Trichomonas Tenax and Entamoeba Gingivalis in Patients with Chronic Periodontitis". Journal of Dentistry. 17 (3): 171–176. ISSN 2345-6485. PMC 5006825. PMID 27602391.

- Mehlhorn, Heinz (2016). "Trichomonas tenax". Human parasites : diagnosis, treatment, prevention. Springer. p. 26. ISBN 9783319328027.

- Kofoid, Charles A.; Hinshaw, H. Corwin; Johnstone, Herbert G. (August 1929). "Animal parasites of the mouth and their relation to dental disease". The Journal of the American Dental Association. 16 (8): 1436–1455. doi:10.14219/jada.archive.1929.0207.

- Chen, Jinfu; Liu, Guangying; Zeng, Guoqi; Wen, Wangrong (1997). "[Trichomonas tenax culture in vitro]". Journal of Fujian Medical College (in Chinese). 31 (2). ISSN 1000-2235.

- Dehghan, Mojdeh; Tantbirojn, Daranee; Kymer-Davis, Emily; Stewart, Colette W.; Zhang, Yanhui H.; Versluis, Antheunis; Garcia-Godoy, Franklin (May 2017). "Neutralizing salivary pH by mouthwashes after an acidic challenge". Journal of Investigative and Clinical Dentistry. 8 (2): e12198. doi:10.1111/jicd.12198. ISSN 2041-1626. PMID 26616243.

- Dybicz, Monika; Perkowski, Konrad; Baltaza, Wanda; Padzik, Marcin; Sędzikowska, Aleksandra; Chomicz, Lidia (25 September 2018). "Molecular identification of Trichomonas tenax in the oral environment of domesticated animals in Poland – potential effects of host diversity for human health". Annals of Agricultural and Environmental Medicine. 25 (3): 464–468. doi:10.26444/aaem/92309. PMID 30260189.

- Kellerová, Pavlína; Tachezy, Jan (April 2017). "Zoonotic Trichomonas tenax and a new trichomonad species, Trichomonas brixi n. sp., from the oral cavities of dogs and cats". International Journal for Parasitology. 47 (5): 247–255. doi:10.1016/j.ijpara.2016.12.006. PMID 28238869.

Further reading

Dimasuay, Kris Genelyn B.; Rivera, Windell L.; Fontanilla, Dr. Ian Kendrich C. (April 2014). "First report of Trichomonas tenax infections in the Philippines". Parasitology International. 63 (2): 400–402. doi:10.1016/j.parint.2013.12.015. PMID 24406842.