Alouette 1

Alouette 1 is a deactivated Canadian satellite that studied the ionosphere. Launched in 1962, it was Canada's first satellite, and the first satellite constructed by a country other than the Soviet Union or the United States. Canada was the fourth country to operate a satellite, as the British Ariel 1, constructed in the United States by NASA, preceded Alouette 1 by five months.[4] The name "Alouette" came from the French for "skylark"[5] and the French-Canadian folk song of the same name.

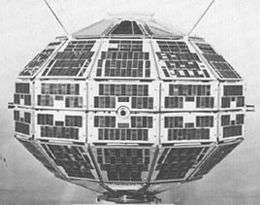

The Alouette 1 satellite | |

| Mission type | Ionospheric |

|---|---|

| Operator | DRDC |

| Harvard designation | 1962 Beta Alpha 1 |

| COSPAR ID | 1962-049A |

| SATCAT no. | 424 |

| Spacecraft properties | |

| Manufacturer | Defence Research Telecommunications Establishment |

| Launch mass | 145.6 kilograms (321 lb) [1] |

| Start of mission | |

| Launch date | 29 September 1962, 06:05 UTC |

| Rocket | Thor DM-21 Agena-B |

| Launch site | Vandenberg LC-75-1-1 |

| End of mission | |

| Deactivated | 1972 |

| Orbital parameters | |

| Reference system | Geocentric |

| Regime | Low Earth |

| Semi-major axis | 7,381 kilometres (4,586 mi)[2] |

| Eccentricity | 0.0023678[3] |

| Perigee altitude | 985 kilometres (612 mi)[3] |

| Apogee altitude | 1,020 kilometres (630 mi)[3] |

| Inclination | 80.4656 degrees[3] |

| Period | 105.18 minutes[3] |

| Epoch | 26 April 2016 03:03:44 UTC[3] |

A key device on Alouette were the radio antennas consisting of thin strips of beryllium copper bent into a slight U-shape and then rolled up into small disks in a fashion similar to a measuring tape. When triggered, the rotation of the satellite created enough centrifugal force to pull the disk away from the spacecraft body, and the shaping of the metal caused it to unwind into a long spiral. The result was a stiff circular cross-section antenna known as a "stem", for "storable tubular extendible member".[6]

History

Mission background

Alouette 1 was part of a joint U.S.-Canadian scientific program.[7] Its purpose was to investigate the properties of the top of the ionosphere, and the dependence of those properties on geographical location, season, and time of day.[8] Alouette 1 was advanced for its time, and NASA initially doubted whether the available technology would be sufficient. Nevertheless, NASA was eager to collaborate with international partners.[9] NASA was convinced to participate by the prospect of obtaining data on the ionosphere, and Canada had the additional objective of developing its own space research programme.[9] The United Kingdom also aided the mission by providing support at two ground stations, in Singapore and at Winkfield.[10]

Satellite launch and mission progress

Alouette 1 was launched by NASA from the Pacific Missile Range at Vandenberg Air Force Base, California, USA at 06:05 UTC on September 29, 1962, into orbit around Earth. It was placed into an almost circular orbit with an altitude of 987 kilometres (613 mi) to 1,022 kilometres (635 mi) with an inclination of 80.5°.[11] The launch made Canada the third nation, after the USSR and the United States, to design and construct its own satellite.[12] Alouette was used to study the ionosphere, using over 700 different radio frequencies to investigate its properties from above.[13]

The satellite was initially spin-stabilised, rotating 1.4 times per minute. After about 500 days, the rotation had slowed to about 0.6 rpm and the spin-stabilisation failed at this point. It was then possible to determine the satellite's orientation only by readings from a magnetometer and from temperature sensors on the upper and lower heat shields.[14] The orientation determinations obtained this way were only accurate to within 10 degrees. It is likely that gravitational gradients had caused the longest antenna to point towards the Earth.[15]

A 2010 technical report by the US Defense Threat Reduction Agency titled "Collateral Damage to Satellites from an EMP Attack” [16] lists Alouette 1 among the satellites damaged by residual radiation from the July 9, 1962 Starfish Prime high-altitude nuclear test conducted by the United States. Another article, titled "Anthropogenic Space Weather",[17] indicates Alouette 1 sustained no significant adverse effects from the Starfish radiation, most likely due to a very conservative power supply design that allowed for a 40% degradation of solar cell performance.

Alouette's mission lasted for 10 years before the satellite was deliberately switched off on 30 September 1972.[18] The satellite remains in orbit; in 1966 it was estimated that Alouette 1 would remain in orbit for 1000 years.[19]

Duplicate construction

Two satellites were built for redundancy in case of a malfunction; if the first unit failed, the second could be launched with only a couple of months delay. It took 3 1⁄2 years after Alouette's proposal to have it developed and built.[20] The satellites S27-2 (prototype), S27-3 (which became the launched satellite), and S27-4 (which became the backup) were assembled by Defence Research Telecommunications Establishment (DRTE) Electronics Lab in Ottawa. The mechanical frame and the deployable STEM antennas were made by Special Products and Applied Research Aerospace (SPAR Aerospace), a former division of de Havilland Canada (DHC) in Downsview, Ontario, in a building which many years later (until 2012) housed the Canadian Air and Space Museum. The batteries used for Alouette were developed by the Defence Chemical, Biological, and Radiation Laboratory (DCBRL), another branch of DRB, and were partially responsible for the long lifetime of the satellite. The "Storable Tubular Extendable Member" antennas used were the first of DHC's STEM antennas used in space, and at launch were the longest (125 feet tip to tip).[21] When completed Alouette weighed 145 kg (320 lb) and was launched from a Thor-Agena-B two-stage rocket. Alouette 1's backup was later launched as Alouette 2 in 1965 to "replace" the older Alouette 1.

Experiments

Alouette 1 carried four scientific experiments:

- Sweep-Frequency Sounder. This experiment measured the electron density distribution in the ionosphere by measuring the time delay between the emission and return of radio pulses.[22] The sounder was able to emit pulses with frequencies between 1 and 12 megahertz, with a power of 100 W.[8]

- Energetic particle detectors. An arrangement of Geiger counters and scintillators for detecting energetic particles.[23]

- VLF Receiver. An experiment for measuring both artificial and natural VLF signals.[24] It was sensitive to frequencies between 400 and 10,000 Hz.[8]

- Cosmic Radio Noise. Two long radio antennas for detecting radio noise from the Sun and the Galaxy.[25]

The satellite did not have a tape recorder to store data.[14] It was only possible to obtain data when the satellite was in range of a receiving station.[15]

Post mission

After Alouette 1 was launched, the upper stage of the rocket used to launch the satellite became a derelict object that would continue to orbit Earth for many years. As of October 2018, the upper stage remains in orbit.[26]

The satellite itself became a derelict, remaining in Earth orbit as of October 2018.[27]

The Alouette 1 was named an IEEE Milestone in 1993.[28] It is featured on the Amory Adventure Award.

See also

- Timeline of artificial satellites and space probes

- Prince Albert Radar Laboratory (used as the initial ground station)

References

- Saxena, Ashok K. (1978), "Appendix 1", in Wertz, James R. (ed.), Spacecraft Attitude Determination and Control, Astrophysics and Space Science Library, 73, Dordrecht, Holland: D. Reidel Publishing Company, pp. 788–789, ISBN 90-277-0959-9

- "ALOUETTE 1 (S-27)". N2YO.com. 2016-04-26. Retrieved 2016-04-26.

- Peat, Chris (2016-04-26). "Alouette 1 - Orbit". Heavens Above. Retrieved 2016-04-26.

- Palimaka, John. "The 30th Anniversary of Alouette I". IEEE.

- Helen T. Wells; Susan H. Whiteley; Carrie E. Karegeannes. Origin of NASA Names. NASA Science and Technical Information Office. p. 10.

- "Antenna material". Ingenium. Retrieved 23 July 2018.

- Houghton, J. T.; Taylor, F. W.; Rodgers, C. D., Remote Sounding of Atmospheres, Cambridge Planetary Science Series, 5, Cambridge University Press, p. 234, ISBN 0521310652

- Kramer, Herbert J. (2002). Observation of the Earth and its Environment: Survey of Missions and Sensors (4 ed.). Berlin: Springer. ISBN 3540423885.

- Rakobowchuk, Peter (8 September 2012), "NASA once thought Canada's famed Alouette-1 satellite was too ambitious: space engineer", National Post, retrieved 1 May 2015

- Le Galley, Donald P. (1964), "1", in Le Galley, Donald P.; Rosen, Alan (eds.), Space Physics, Univer1sity of California Engineering and Physical Sciences Extension Series, John Wiley and Sons, p. 36

- Darling, David (3 Jun 2003). The Complete Book of Spaceflight: From Apollo 1 to Zero Gravity. Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 0471056499.

- "Alouette I and II". Canadian Space Agency. 3 March 2012.

- Gainor, Chris (2012), Alouette 1 - Celebrating 50 Years of Canada in Space, SpaceRef, archived from the original on 2015-04-17

- Angelo, Joseph A. (2006). Encyclopedia of Space and Astronomy. New York: Infobase Publishing. p. 22. ISBN 978-0-8160-5330-8.

- Grayzeck, Ed (26 August 2014). "Alouette 1". NASA. Retrieved 18 April 2014.

- Conrad, Edward E., et al. "Collateral Damage to Satellites from an EMP Attack" Report DTRA-IR-10-22, Defense Threat Reduction Agency. August 2010 (Retrieved May 27, 2019)

- T. I. Gombosi., et al. "Anthropogenic Space Weather" Space Science Reviews. 10.1007 (Page 26, Table 2) (Retrieved May 27, 2019)

- Baker, David (2004). Jane's Space Directory. Jane's Information Group. p. 471.

- "Space trash, and an inventory of hardware in orbit". LIFE. 61 (6): 29. 1966.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2012-07-19. Retrieved 2012-07-06.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Al Bingham, S27-3 Electronics Technologist

- "Sweep-Frequency Sounder". NASA. 26 August 2014. Retrieved 30 September 2014.

- "Energetic Particles Detectors". NASA. 26 August 2014. Retrieved 30 September 2014.

- "VLF Receiver". NASA. 26 August 2014. Retrieved 30 September 2014.

- "Cosmic Radio Noise". NASA. 26 August 2014. Retrieved 30 September 2014.

- "Alouette 1 Rocket - Satellite Information". satellite database. Heavens-Above. Retrieved 2013-09-25.

- "Alouette 1 - Satellite Information". satellite database. Heavens-Above. Retrieved 2013-09-25.

- "Milestones:Alouette-ISIS Satellite Program, 1962". IEEE Global History Network. IEEE. Retrieved 29 July 2011.