Allen Jones (artist)

Allen Jones RA (born 1 September 1937) is a British pop artist best known for his paintings, sculptures, and lithography. He was awarded the Prix des Jeunes Artistes at the 1963 Paris Biennale. He is a Senior Academician at the Royal Academy of Arts. In 2017 he returned to his home town to receive the award Honorary Doctor of Arts from Southampton Solent University

Allen Jones | |

|---|---|

| Born | 1 September 1937 Southampton, England |

| Nationality | British |

| Education | Royal College of Art |

| Alma mater | Hornsey College of Art |

| Known for | Sculptor, painter, artist, educator |

Notable work | Life Class (1968) Chair (1969) The Tango (1984) |

| Style | Abstract expressionism |

| Movement | Pop art |

| Awards | Prix des Jeunes Artistes (1963), Honorary Doctor of Arts, Southampton Solent University (2017) |

Jones has taught at the Hochschule für bildende Künste Hamburg, the University of South Florida, the University of California, the Banff Center School of Fine Arts in Canada, and the Berlin University of the Arts. His works reside in a number of collections; including the Tate, the Museum Ludwig, the Warwick Arts Centre and the Hirshhorn Museum.[1] His best known work Hatstand, Table and Chair, involving fibreglass "fetish" mannequins, debuted to protests in 1970.

Early life and education

| "For my generation anyone who wanted to cut the mustard had to reckon with Abstract Expressionism.... I've never wanted to show the struggle involved in the making of the work, and to make it part of the painting the way it is with Pollock or de Kooning. That's just not me; constitutionally I couldn't abandon the figure. But I had to find a new way of doing it. Abstract Expressionism had swept everything away. You couldn't go back to representing the figure through some moribund visual language." |

| — Allen Jones in a 2014 interview[2] |

Jones was born in the English city of Southampton on 1 September 1937. The son of a Welsh factory worker, he was raised in the west London district of Ealing,[2] and in his youth attended Ealing County Grammar School for Boys. Jones had an interest in art from an early age. In 1955, he began studying painting and lithography at Hornsey College of Art in London, where he would graduate in 1959.[2] At the time the teaching method at Hornsey was based on Paul Klee's Pedagogical Sketchbook from the 1930s. While a student at Hornsey, Jones travelled to Paris and the French region of Provence, and was particularly influenced by the art of Robert Delaunay.[3] He also attended a Jackson Pollock show at the Whitechapel Gallery in 1958, and according to Jones, "for me it was outside any known frame of reference. The scale, the ambition, the freedom. I felt like suing my teachers for not telling me what was happening in the world."[2] He afterwards travelled to see the Musie Fernand Léger in the French commune of Biot,[3] and in 1959 he left Hornsey to begin attending the Royal College of Art.[4]

As one of the first British pop artists, Jones produced increasingly unusual paintings and prints in the late 1950s and early 1960s, and in particular enjoyed combining different visual languages to expose the historical constructions underlying them.[5] According to Jones, about his early ambitions, "I wanted to kick over the traces of what was considered acceptable in art. I wanted to find a new language for representation... to get away from the idea that figurative art was romantic, that it wasn't tough."[2] He was part of a unique generation of students at the Royal College, among which his fellow students were R. B. Kitaj, Peter Phillips, David Hockney, and Derek Boshier, but was expelled from the Royal College of Art in 1960, at the end of his first year.[6] Explained by Mark Hudson in The Telegraph many years later, "horrified at the new developments brewing among their younger students, the college's academic old guard decided to make an example of someone. They chose Jones."[2] Dismayed, Jones signed up for a teacher training course and returned to his studies at Hornsey College of Art in 1960, graduating the following year.[4][7]

Art career

Early teaching and exhibits (1961–63)

Despite his expulsion from the Royal College, in January 1961 Jones' work was included in the Young contemporaries 1961 exhibit. The annual Royal Society of British Artists exhibition was described in the press as "the exhibition that launched British pop art,"[2] Young Contemporaries helped expose England to the art of Jones, David Hockney, R. B. Kitaj, Billy Apple, Derek Boshier, Joe Tilson, Patrick Caulfield, and Peter Blake, all of whom were variously influenced by American Pop.[8] Among his works, Jones entered several paintings of London buses on shaped canvases, which were afterwards put on display at the London West End gallery Arthur Tooth & Sons. One of the gallery's directors then introduced Jones to the work of American pop artists such as Andy Warhol, Roy Lichtenstein and Claes Oldenburg, which proved inspirational to Jones.[2] In 1961, he took a job teaching lithography at Croydon College of Art in London, where he would remain until 1963. Around this time, Jones was influenced by the works of writers such as Friedrich Nietzsche, Sigmund Freud, and Carl Jung.[3] According to Jones, his 1963 painting Hermaphrodite, depicting "fused male/female couples as metaphors of the creative act," draws from both Freud and Nietzsche.[4] In 1963, Jones was awarded the Prix des Jeunes Artistes at the Paris Biennale.[3] The following year, Jones and other Nouveau réalisme and pop artists such as Peter Phillips and Pauline Boty were featured in documentaries by Belgian director Jean Antoine, Evelyne Axell's husband.[9]

Travel in United States and abroad (1964–69)

| "[In New York City Jones] found a scene dominated by the ideas of the influential critic Clement Greenberg: that the essence of painting lay in the flatness of the canvas, in hard edges, in the painting as object. Jones wanted to create a new kind of art that conformed to those principles... but which retained the human figure. He found the imagery that would allow him to do that in the seedy bookshops of Times Square." |

| — Mark Hudson[2] |

Intrigued by the "toughness" of American pop art, Jones moved to Manhattan in 1964 and took a studio at the Chelsea Hotel. In New York City, Jones recollects learning to "present what you were saying as clearly as possible," and he developed an interest in making his images tangible.[2] For the year Jones remained in the city, he "discovered a rich fund of imagery in sexually motivated popular illustration of the 1940s and 1950s."[4] According to Jones, about his art of the time:

Fetishism and the transgressive world produced images that I liked because they were dangerous. They were about personal obsessions. They stood outside the accepted canons of artistic expression and they suggested new ways of depicting the figure that weren't dressed up for public consumption."[2]

Among other projects at the time, Jones "worked on a three-dimensional illusionism with obvious erotic components."[3] When Jones' close friend Peter Phillips came to New York on a Harkness Fellowship in 1964, for two years they spent much of their time travelling together throughout the United States.[3] Jones' style continued to develop, and his 1966 painting Perfect Match "made explicit [his] previously subdued eroticism, adopting a precise linear style as a means of emphasizing tactility."[4]

In 1967, Jones' work along with the works of artists such as Piero Gilardi and David Hockney were included in an exhibition for the wedding of Guglielmo Achille Cavellini's daughter.[10] The following year, when the xartcollection exhibition series was created in Zürich, Switzerland, Jones and artists such as Max Bill, Getulio Alviani, and Richard Hamilton were among the first to be included in the company's "multiples." Until it dissolved a few years later, the company's philosophy was to make contemporary art available to a large public by industrially producing three-dimensional "multiples," with several artists' work included on each.[11] Jones was a guest lecturer at the Hochschule für bildende Künste Hamburg in Germany from 1968 to 1970, and in 1969 was also a visiting professor at the University of South Florida.[3] His 1968 set of prints, Life Class, was among his first works to incorporate elements of sculpture. Each print is made of two-halves, the bottom being a realistic pair of women's legs in tights, while the upper halves are drawn in a 1940s fetishist graphic style representing "the secret face of British male desire in the gloomy post-war years."[5] About his further experimentation with sculpture, Jones has stated that "I spent so much time giving my figures that grabbable quality, I thought, why don't I make them in three dimensions?"[2]

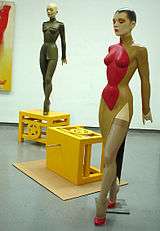

Hatstand, Table and Chair (1970)

| "When I looked at what other avant-garde artists were doing with the figure there was always a kind of prop, something that let the viewer off the hook, that told them 'this is a work of art'. I wanted to make a figure that was devoid of those props. There was an idea I'd seen in an adult comic strip where a person was used as a table, and that set off a whole host of resonances." |

| — Allen Jones[2] |

While living in the London neighbourhood of Chelsea in the late 1960s, Jones began working in sculpture.[12] His fibreglass sculpture Chair, which was completed in 1969, marked the start of a series of "life-size images of women as furniture with fetishist and sado-masochist overtones."[4] The first three sculptures were each sculpted from Jones' drawings, with Jones overseeing professional sculptor as he produced the figures in clay. The three female figures were then cast in plaster by a company that specialised in producing shop mannequins. Each of the original three figures was produced in an edition of six.[13]

| External video | |

|---|---|

Jones first group of erotic fibreglass sculptures, of a Hatstand, Table and Chair gained international attention when exhibited in 1970. The works were met with strong protests for perceived misogyny, which succeeded in making Jones a "cultural hot potato".[5] Laura Mulvey writing for Spare Rib magazine suggested the sculptures was inspired by latent castration anxiety. Almost a decade later, when they were put on display at the Institute of Contemporary Arts in 1978, they were attacked with stink bombs. Eight years later, on International Women's Day, Chair was damaged by paint stripper while exhibited at the Tate.[6] According to art historian and curator, Marco Livingstone, writing in 2004: "More than three decades later, these works still carry a powerful emotive charge, ensnaring every viewer's psychology and sexual outlook regardless of age, gender or experience."[14]

The severe reaction from the art world, feminists, and the mainstream press after the sculptures' debut would limit Jones' exhibition career in England over the next several decades. When asked about their effect on his career, Jones was quoted stating "it's collateral damage. I wanted to offend the canons of accepted worth in art. I found the perfect image to do that, and it's an accident of history that these works coincided with the arrival of militant feminism."[2] Roman Polanski, Elton John and Gunter Sachs all owned a piece at one stage, with one of the sets selling at auction in 2012 for £2.6 million. The sculptures have also been referenced in Stanley Kubrick's 1971 film A Clockwork Orange.[6]

Maîtresse and teaching (1973–1980s)

Jones, photographer Brian Duffy, and air brush specialist Philip Castle were commissioned to collaborate on the annual and often salacious Pirelli calendar in 1973, resulting in a unique edition that Clive James would later jokingly call "the only Pirelli Calendar that nobody bothered to look at twice".[15] In 1973, Jones spent time as a guest lecturer at the University of California, Los Angeles, and after visiting Japan in 1974, the following year he toured Canada.[3] Jones designed Barbet Schroeder's 1975 film Maîtresse.[3] Starring Bulle Ogier as the professional dominatrix Ariane and Gérard Depardieu as her obsessed lover, the film provoked controversy in the United Kingdom because of its graphic depictions of sado-masochism.[16]

By the mid 1970s, he was again focusing on canvas and painting, and among his notable works at this time were Santa Monica Shores in 1977.[4] Now at the Tate, the work was painted while he was a guest lecturer at the University of California, Los Angeles in 1977, and later that summer he was a visiting director of studies in drawing and painting in Alberta, Canada, at the Banff Center School of Fine Arts. Known for only very occasionally taking on commissions, Jones was commissioned to design a hoarding for Fogal, a hosiery manufacturer, at Basel station in 1978. The Walker Art Gallery in Liverpool held a large retrospective exhibition on his work in 1979, and the exhibit later travelled to the Serpentine Gallery in London. Continuing to travel, he was invited by the Berlin University of the Arts to be a guest professor from 1982 to 1983.[3] By that time, he had largely returned to "a playful stylisation in figure sculptures," including The Tango in 1984, a life-size dancing couple made from steel plate.[4] In 1986, his work was included in the Venice Biennale's Art e Scienza exhibition, alongside artists such as Brian Eno and Tony Cragg, and that year he was elected as a Royal Academician by the Royal Academy.[17] Opened in 1987, Birch and Conran was the first art gallery in Soho, and their inaugural show featured British Pop artists such as Jones, Sir Peter Blake, Richard Hamilton, and Clive Barker. From 1990 to 1999, he served as a trustee at the British Museum, and in 2000 became an Emeritus Trustee.[18]

He has works held by the Cass Sculpture Foundation. One of which, the outdoor sculpture Temple from 1998, was

a response to the artifice of cultivated landscape... Jones sought to make a sculpture which used that artifice to distort scale and distance and to manipulate our perception of space. Jones's interest derived from eighteenth-century landscape architects, who did this when introducing decorative buildings and follies into their schemes.[7]

Also, with the figure at top of the structure Jones uses "colour to introduce the notion of movement in the figure, with the alternate arms of yellow and green in diagonally opposing positions."[19]

Recent exhibitions and holdings (2000s)

Jones continued his artistic activity into the 2000s, and among other projects he incorporated leatherwork by Whitaker Malem.[20] In recent years, Jones has increasingly become known for his large steel sculptures, many of which are abstract in nature and feature intertwining figures. A number of them were displayed in an outdoor exhibit in May 2015 at the Art in the Park event held by Lake Zurich.[21] His work is also included in a number of public and private art collections; three of his paintings are in the collection of the Centro de Arte Moderna of the Gulbenkian Foundation in Lisbon,[22] and he has pieces in the Ingram Collection of Modern British Art.[23]

In 2007, he was awarded an honorary Doctorate of Arts from Southampton Solent University.[18] He has had solo exhibitions at the Wetterling Teo Gallery in Stockholm and the Serge Sorokko Gallery. His works featured in the Pop Art Portraits show at the National Portrait Gallery in London, and had a dedicated room of watercolours, drawing and paintings at the Tate Britain. In 2008, he was given a dedicated watercolour room at the Royal Academy of Arts. In April 2013, his work was included in a major exhibition at the National Museum of Wales in Cardiff, titled Pop and Abstract, alongside work by artists like Peter Blake and Bridget Riley.[24] A parody of Jones Chair sculpture was part of a collection exhibited under the name Allen Jones Remake at the Venus Over Manhattan Gallery in New York in 2013.[25] An example of Jones' 1969 Chair sculpture (as well as over fifty other works) remains at the Tate, which was acquired in 2014.[4][13] In November 2014, a retrospective on Jones opened at the Royal Academy of Arts, running until January 2015 in London.[26][27]

Artistic style and influences

Associated with the British Pop art movement of the late 1960s,[5] Jones is known for his work with lithography, painting, drawing, and sculpture. The Cass Sculpture Foundation wrote about Jones' work that "on a flat canvas, painted forms appear sculptural and his three-dimensional works are painterly. He uses colour to describe form, at times with graphic precision, or conversely with an energy and freedom of gesture which is close to direct expression. Similar developments are evident in his printmaking."[7] The Tate has described his output in lithography as "prolific," writing that it "proved an appropriate medium for his graphic flair."[4] Artists and pop fashion designers such as Alexander McQueen, Issey Miyake and Richard Nicoll have cited Jones as an influence on their own styles.[26]

Jones is known for incorporating erotic imagery into his works, including rubber fetishism and BDSM, and this sexuality has often been a focus of both art critics and the press.[20] Mark Hudson wrote in 2014 that Jones' "subjects have included musicians, dancers and London buses, but in the popular perception his name is irrevocably linked to his peerlessly kinky fetish women, whether in two or three dimensions, with their machined surfaces and blank expressions – images that are as emblematic of classic British pop art as Peter Blake's Beatles paintings or Hockney's swimming pools."[2] In a review on Jones' career, Richard Dorment wrote in November 2014 that "you could argue that Jones's work isn't really about women; it's about men and how they look at and think about women. Men use various strategies to neutralise or control desire. One is to fetishise the female body...[while] another is for the man to appropriate it."[28]

Dorment further explains himself by writing that

turn to Jones's paintings, and you see that he explores the theme of men transformed into women again and again. A man dancing with a woman becomes inextricably fused into her body; another trades trousers and brogues for stockings and heels, as he walks from one edge of the canvas to the other...

Dorment further opines that "the paintings... show men and women in sexual situations, but they are joyous and liberated and self-indulgent in a way that the lugubrious mannequins aren't."[28] Wrote Catrin Davies for Twin Factory in November 2014 about the show,

Jones' paintings provide a little counterbalance to the implied misogyny of his sculptures. In these colourfully kitsch scenes he paints about power-play with cross-dressing inferences, of the dominate female, the submissive male, of the animalistic rituals of mating and the delicate interplay of coupling represented in the form of dance.[27]

Personal life

Jones lives and works in London, England.[2]

Notable works

- Interesting Journey (oil on canvas, 1962; British Council)

- Bikini Front (oil on canvas, 1962; Feigen Gallery New York. Chicago, Los Angeles)

- Figure Falling / Chute (1964; held at Museum Ludwig)

- Perfect Match / Partenaire idéale (1966–1967; held at Museum Ludwig)

- Hermaphrodite (painting from 1963; Liverpool, Walker A.G.)[4]

- First Step (oil on canvas, 1966; Marzotto European Touring Show 1966/7)

- Perfect Match (painting from 1966–7; Cologne, Mus. Ludwig)[4]

- Shoe Box (lithography set, 1968)[5]

- Chair (sculpture, 1969; Tate, London)[4]

- Hatstand (sculpture, 1969; shown in 2012–13 Off The Wall touring retrospective, Germany: Kunsthalle Tübingen; UNESCO World Heritage Site, Völklinger Hütte, Saarbrüken Region; State Art Collection, Chemnitz)

- Table (Sculpture, 1969; Shown in 2012–13 Off The Wall touring retrospective, Germany: Kunsthalle Tübingen; UNESCO World Heritage Site, Völklinger Hütte, Saarbrüken Region; State Art Collection, Chemnitz)

- Santa Monica Shores (painting from 1977; London, Tate)[4]

- The Tango (sculpture from 1984; owned jointly by Liverpool, Walker A.G., and Merseyside Development Corp.)[4]

- Temple (sculpture from 1988; on display at Cass Sculpture Foundation)[7]

- Two to Tango (large steel sculpture; on display at Taikoo Place in China)[29]

- Interval (oil on canvas, 2007; 2012 Centre for European Art Völklinger Hütte, Saarbrüken Region)

Exhibitions and publications

| Debut | Title | Description | Release details |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1963 | Solo exhibition | Solo exhibition | Arthur Tooth and Sons in London (1963) |

| 1967 | Solo exhibition | Solo exhibition | Galerie Der Spiegel in Cologne, Germany (1967) |

| 1969 | Figures | Publication | Milan (1969)[4] |

| 1970 | Solo exhibition | Solo exhibition | Galerie Rudolf Zwirner in Cologne, Germany (1967) |

| Hatstand, Table and Chair | Sculpture exhibit | Institute of Contemporary Arts (1970), etc. | |

| 1971 | Projects | Publication | London (1971), included designs for stage, film, TV[4] |

| 1972 | Solo exhibition | Solo exhibition | Marlborough Fine Art in London (1972) |

| 1974 | Solo exhibition | Solo museum exhibition | Seibu in Tokyo, Japan (1974) |

| 1975 | Maîtresse | Set design | Directed by Barbet Schroeder |

| Solo exhibition | Solo museum exhibition | Fruitmarket Gallery in Edinburgh, Scotland (1975) | |

| 1976 | Solo exhibition | Solo exhibition | Waddington Galleries in London (1976) |

| 1977 | Solo exhibition | Solo exhibition | James Corcoran Gallery in Los Angeles, California (1977) |

| 1978 | Retrospective of drawings and watercolours | Solo retrospective | Institute of Contemporary Art in London (1978) |

| 1979 | Solo exhibition | Retrospective exhibit | Walker Art Gallery, Liverpool[3] |

| Retrospective 1959–1978 | Solo exhibition | Serpentine Gallery in London (1979), then to the Walker Art Gallery in Liverpool, Germany, etc. | |

| 1985 | Solo exhibition | Solo exhibition | Galerie Parice Trigano in Paris, France (1985) |

| Solo exhibition | Solo exhibition | Galerie Kaj Forsblom in Helsinki, Finland (1985) | |

| 1988 | Solo exhibition | Solo exhibition | Charles Cowles Gallery in New York City (1988) |

| 1992 | Solo exhibition | Solo exhibition | Frank Pages Art Gallery in Baden-Baden, Germany (1992) |

| 1993 | Solo exhibition | Solo exhibition | Galerie Mourmans in Knokke, Belgium (1993) |

| 1995 | Solo exhibition | Solo exhibition | Barbican Art Gallery in London (1995) |

| 1996 | Solo print retrospective | Solo exhibition | Galleria Civica, Modena, Italy (1996) |

| 1997 | Solo watercolours exhibition | Solo exhibition | Thomas Gibson Fine Art in London (1997) |

| 1998 | Solo exhibition | Solo exhibition | Marino alla Scala Art Center, Fondazione Trussardi, Milan, Italy (1998) |

| 1999 | Solo exhibition | Exhibit | Academy, Helsinki[17] |

| 2000 | Solo exhibition | Solo exhibition | Kunsthaus in Köln, Germany (2000) |

| 2002 | Royal Academy Summer Exhibition | Dedicated room | London (2002) |

| 2003 | Solo exhibition | Exhibit | Alan Crisea Gallery, London[17] |

| 2007 | Solo exhibition of watercolours, paintings, drawings | Dedicated room | Tate Britain (2007–2008) |

| 2009 | Solo exhibition | Exhibit | Gallerie Patrice Trigano, Paris[17] |

| "Figures Waiting" sculptures | Sculpture exhibition | Ludlow Castle in Shropshire (200) | |

| 2012 | Off The Wall | Solo exhibition | Kunsthalle Tubigen; Unesco World Heritage Site, Volklinger Hutte, Saarbrücken; State Art Collection, Chemnitz, Germany |

| 2013 | Solo exhibition | Solo exhibition | Galerie Hilger in Vienna, Austria (200) |

| 2013 | Allen Jones Retrospective | Exhibit | Royal Academy in London (13 November 2014 – 25 January 2015)[30] |

See also

References

- "University of Warwick Art Collection – View by Location".

- Hudson, Mark (7 November 2014). "Allen Jones: 'The thing about eroticism is that it forces a response'". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 25 June 2015.

- "Allen Jones Biography". phinnweb.org. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 25 June 2015.

- Livingstone, Marco. "Allen Jones Artist biography". The Tate. Retrieved 25 June 2015.

- Sladen, Mark (June–August 1995). "Allen Jones". frieze (23). Archived from the original on 21 February 2014. Retrieved 3 February 2014.

- Wroe, Nicholas (31 October 2014). "Allen Jones: 'I think of myself as a feminist'". The Guardian. Retrieved 26 August 2015.

- "Allen Jones". Cass Sculpture Foundation. Archived from the original on 24 February 2016. Retrieved 30 June 2015.

- Barton, Christina (2010). Billy Apple: British and American Works 1960–69. London: The Mayor Gallery. pp. 11–21. ISBN 9780955836732.

- Allmer, Patricia; eds, Hilde Van Gelder (2007). Collective Inventions: Surrealism in Belgium. Leuven, Belgium: Leuven University Press. p. 155. ISBN 9789058675927.

- Cavellini, Guglielmo Achille (1989). Vita di un genio (in Italian). Brescia: Centro Studi Cavelliniani. p. 27.

- Judith, Goldman (1994). The Pop Image: Prints and Multiples. New York, NY: Malborough Graphics. p. 111. ISBN 9780897971041.

- Gayford, Martin (8 October 2007). "Allen Jones: The day I turned down Stanley Kubrick". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 3 February 2014.

- "Allen Jones: Chair 1969". Tate Gallery. Retrieved 3 February 2014.

- Guadagnini, Walter (2004). Pop Art UK : British Pop Art 1956–1972. Milan: Silvana. pp. 160–161. ISBN 9788882157470.

- James, Clive (3 June 1979). "While there's Hope". The Crystal Bucket.

- "Maitresse". British Board of Film Classification. Retrieved 26 August 2015.

- Allen Jones at The Royal Academy of Arts

- "Allen Jones R.A. Official CV". Allen Jones.

- "Temple 1998". Cass Sculpture Foundation. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 30 June 2015.

- Fury, Alexander (26 October 2014). "'Fetishism and fashion? It's a perfect match...'". The Independent. Retrieved 26 October 2014.

- Will, Rachel (19 May 2015). "See Allen Jones' Steel Sculptures in a Garden Atmosphere at Baur Au Lac Hotel". Blouinartinfo. Retrieved 30 June 2015.

- Search the Collection, Cam.gulbenkian.pt. Retrieved 2 February 2014.

- Brown, Mark (7 May 2012). "The Gunter Sachs appeal – life and legacy of the playboy art collector". The Guardian. Retrieved 26 August 2015.

- "Pop and Abstract". National Museum Wales. Retrieved 15 October 2014.

- Fairs, Marcus (21 January 2014). "Russian gallerist sparks race row over 'overtly degrading' chair". Dezeen Magazine. Retrieved 3 February 2014.

- Nicoll, Richard (14 November 2014). "Richard Nicoll: 'Why I love Allen Jones'". The Guardian. Retrieved 30 June 2015.

- Davies, Catrin (20 November 2014). "Allen Jones RA". Twin Factory. Retrieved 30 June 2015.

- Dorment, Richard (10 November 2014). "Allen Jones, Royal Academy, review: 'dangerous, perverse and brilliant'". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 25 June 2015.

- "Two to Tango". Taikoo Place. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 30 June 2015.

- "Allen Jones RA Exhibition (13 November – 25 January 2015)". Royal Academy of Arts. Retrieved 25 June 2015.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Allen Jones (sculptor). |

- 19 paintings by or after Allen Jones at the Art UK site

- Profile on Royal Academy of Arts Collections

- Allen Jones at The Royal Academy of Arts