All Saints' Church, Shuart

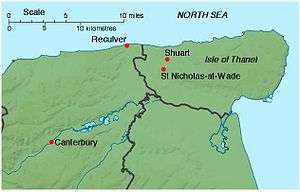

All Saints' Church, Shuart (/ˈʃoʊɑːt/), in the north-west of the Isle of Thanet, Kent, in the south-east of England, was established in the Anglo-Saxon period as a chapel of ease for the parish of St Mary's Church, Reculver, which was centred on the north-eastern corner of mainland Kent, adjacent to the island. The Isle of Thanet was then separated from the mainland by the sea, which formed a strait known as the Wantsum Channel. The last church on the site was demolished by the early 17th century, and there is nothing remaining above ground to show that a church once stood there.

The area of the Isle of Thanet where All Saints' Church stood had been settled since the Bronze Age, and land in the west of the Isle of Thanet was given to the church at Reculver in the 7th century. All Saints' Church remained a chapel of ease for the parish of Reculver until the early 14th century, when the parish was broken up to form separate parishes for Herne and St Nicholas-at-Wade. The area served by All Saints' was merged with that of St Nicholas-at-Wade, which became the centre of a new parish with All Saints' as its chapel. The churches of All Saints and St Nicholas continued to have a junior relationship with the parish of Reculver, making annual payments to the church there.

All Saints' originally consisted of a nave and chancel, to which a sanctuary was added in the first building phase. The church was extended on three occasions between the 10th and 14th centuries – a period of population growth – to include an aisled nave, a western tower and a northern chapel; its windows featured stained glass. The church was abandoned in the 15th century, presumably because the parish could no longer support two churches. It was demolished, and virtually all of its masonry removed, some of which may have been used in improvements to the church of St Nicholas. The settlement of Shuart remained as an area of local administration into the 17th century, but it is now regarded as a deserted medieval village. There were no visible remains of All Saints' Church by 1723, although land there remained as glebe belonging to the parish of St Nicholas. The site of All Saints' Church was excavated by archaeologists between 1978 and 1979. The main structure had been robbed of its materials leaving only the foundations, from which the archaeologists were able to interpret the history of the building's construction and its form. Among the foundations were discovered numerous stone carvings, floor tiles, remnants of stained glass, and several disturbed graves.

Origin

The place-name "Shuart" is from the Anglo-Saxon language and means a skirted, or cut-off, piece of land.[1][Fn 1] The earliest evidence of human settlement at Shuart dates to the Bronze Age; a rectangular Bronze Age enclosure lies a little to the north of the site of All Saints' Church, and a collection of objects from that period, known as the "Shuart Hoard", was found south-west of the site in the 1980s.[2][3] Occupation continued through the Iron Age and the Roman period. Structures, pottery and glass dating to these times have been found nearby, as well as human burials and cremations.[4]

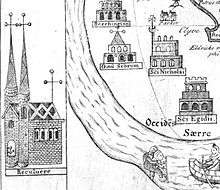

The site's history in the Anglo-Saxon period begins with the division of the Isle of Thanet into eastern and western parts during the 7th century. The division is attributed in medieval sources to the route taken by a tame female deer that was set free to run across the island by Æbbe, founder and first abbess of the double monastery at Minster-in-Thanet, thereby marking out its endowment.[5][6][7] The route was circuitous, beginning on the north side of the island at Westgate-on-Sea and ending on the south side at Sheriff's Court, halfway between Minster-in-Thanet and Monkton, which are about 1.75 miles (3 km) apart.[8] While land to the east of this route was given to Æbbe for her monastery, which was in existence by 678, land to the west, described broadly as Westanea, or "the western part of the island", was given to the monastery at Reculver by King Hlothhere of Kent in 679.[9] This division of the island is apparent in Domesday Book, which was compiled in 1086, and remained an important feature in the early 15th century, when it was included prominently in a map of the island drawn up by Thomas Elmham.[10][11][12] According to Edward Hasted the division was still marked in 1800 by "a bank, or lynch, which goes quite across the island, and is commonly called St. Mildred's lynch."[13]

The monastery at Reculver had been established in 669, and developed as the centre of a "large estate, a manor and a parish".[14] By the early 9th century it had become "extremely wealthy",[15] but it then came under the control of the archbishops of Canterbury.[16] By the 10th century the church and its estate appear to have fallen into royal hands, since King Eadred of England gave them in 949 to Christ Church, Canterbury, now known as Canterbury Cathedral.[17] The Anglo-Saxon charter recording the gift shows that the Reculver estate still included land in the west of the Isle of Thanet at that time.[18][19] Two slightly earlier charters give a more complicated picture: in 943, King Edmund I of England gave land at St Nicholas-at-Wade to a layman,[20][21] and in the next year he gave the same layman land at Monkton, by means of a charter recording that land to the west and north of Monkton – evidently at Sarre – was nonetheless still regarded as belonging to Reculver, rather than to either the archbishop or the king.[22][19] However, while Edmund I's mother Eadgifu gave lands in Kent, including Monkton, to Christ Church in 961, all of the documents recording these transactions entered the Christ Church archive;[23] and, if the land that Christ Church acquired on the Isle of Thanet in the 10th century was the same as the "Liberty" shown on Thomas Elmham's map from the early 15th century, then the site of All Saints' Church, Shuart, must have been included.[11][24] Neither Shuart nor St Nicholas-at-Wade are mentioned by name in Domesday Book;[25] but they may have been included in the entry for Reculver, which was then recorded as a hundred in its own right, and was held entirely by the archbishop of Canterbury, but for a portion held from him by a tenant.[25][26] An analysis of the archbishop's holdings in Domesday Book concludes that All Saints' was among them.[27]

Church and community

A church dedicated to All Saints was established at Shuart some time between 679 and the 10th century.[11] Although the status of the church at Reculver as mother church for the area dates from the 7th century, and may have led to the establishment of a church at Shuart then, this chapel might equally have been a development in response to acquisition of land in the area by Christ Church, Canterbury, in the mid-900s. Examination of the building's archaeological remains has failed to provide a more precise date,[28] but a church stood at Shuart for about 100 years or more before the establishment of a nearby church at St Nicholas-at-Wade, since the earliest church there was "almost certainly built in the late 11th century".[29]

First church

The original church of All Saints was a rectangular building aligned on an east-west axis, measuring 52.5 feet (16 m) by 15.75 feet (5 m). It consisted of a western nave and an eastern chancel, with a sanctuary added to the eastern end of the chancel in the first phase of building.[30] The chancel was about 16.4 feet (5 m) long, and the nave was small, taking up only about 9.2 feet (3 m) of the building's overall length. They were connected by a recessed passageway about 9.8 feet (3 m) long but only about 8.9 feet (3 m) across at its narrowest, the foundations for which suggest a heavy structure, perhaps including a vaulted ceiling.[31] The size of the community this church was originally built to serve is unknown, although Domesday Book records the presence of 90 villeins and 25 bordars in the manor of Reculver in 1086, which included land on the Isle of Thanet, but consisted mainly of land in mainland Kent. Those numbers can be multiplied four or five times to account for dependants, since they only represent adult male heads of households; Domesday Book does not say where in the manor they lived.[25][32][Fn 2]

Expansion

A second phase of building was undertaken between the 10th and 11th centuries, in which the church was enlarged. The west wall was demolished, allowing the nave to be extended to the west by 16.5 feet (5 m), and the passageway between it and the chancel was opened out and replaced with a lighter chancel arch.[33] A third phase followed in the 12th century, when the nave was rebuilt as a much larger structure with north and south aisles, each lined by four columns, and measuring about 30 feet (9 m) wide by 42 feet (13 m) long.[34] A tower about 16.2 feet (5 m) square was added to the western end of the church either at this time or in a fourth phase of building carried out in the 13th century.[34] This fourth phase involved the installation of new windows featuring stained glass, especially at the eastern end of the nave, comparable to the grisaille glass still in the south transept of York Minster that dates from about 1240.[35] A chapel was also added to the north side of the church, measuring about 12.5 feet (4 m) wide by 29.4 feet (9 m) long, with an altar at its eastern end, and paved with tiles about 4 inches (10 cm) square.[36] Flemish floor tiles were also installed in the church, probably in the 15th century.[37][38]

The expansion of the church coincided with a period of growth in the population of Reculver parish as a whole, which had expanded to more than 3,000 people by the late 13th century.[39] The first record to mention All Saints' explicitly dates from 1284, when the community it served complained to the archbishop of Canterbury that the vicar of Reculver had failed to provide a chaplain to celebrate daily mass.[40] In 1296 the archbishop settled a dispute concerning a duty to pay for repairs to the church, specifying that this was owed by owners of property on and around part of "North Street".[41][Fn 3] In 1310 Archbishop Robert Winchelsey of Canterbury established St Nicholas-at-Wade as a separate parish, with All Saints' Church as its chapel, served by a vicar and an assistant priest.[43][44] According to the document by which that was done, the population of the parish of Reculver had grown so large that the provision of a single vicar had become inadequate.[45][39][Fn 4] While Thanet was then still an island separated from the rest of Kent by the Wantsum Channel, the new arrangement was also prompted by the inconvenience posed by the distance between these chapels on the Isle of Thanet and their mother church at Reculver.[46][Fn 5] However, the document specified that the vicar of the new parish of St Nicholas-at-Wade had to pay £3.3s.4d (£3.17) annually to the vicar of Reculver "as a sign of subjection".[48][Fn 6] The vicar also had to go to Reculver "in procession"[49] with his assistant priest and his parishioners every year on Whit Monday – the eighth day after Easter – as well as being present at Reculver for the Nativity of the Virgin Mary, the patron saint of Reculver, on 8 September.[49][Fn 7] The visits to Reculver continued in the mid-16th century, when they were recorded by John Leland,[50] and the parish of St Nicholas-at-Wade was still making annual payments to Reculver in the 19th century.[51] Archbishop Winchelsey's instructions also set out relative values for the parishes of Reculver and St Nicholas-at-Wade, in allocating dues for taxes known as "clerical tenths".[49][Fn 8] Reculver was liable for 12s.1d (60.5p), compared to St Nicholas-at-Wade's liability of 11s.4d (57p).[49] The first vicar of St Nicholas-at-Wade was named by Archbishop Winchelsey as Andrew de Grantesete.[49]

Decline

Thomas Elmham's map of the Isle of Thanet, drawn in the early 15th century, shows the church with its tower, but a map of 1596 by Philip Symonson, which shows churches "as they actually appeared",[37] shows a church without a tower.[37][Fn 9] Examination of the church's foundations indicates that it was probably a ruin by the middle of the 15th century and was demolished, but was replaced by a smaller structure, without a tower, up to 20 years later.[53] It may be that material from All Saints' Church was used in the construction of a new clerestory for the nave of St Nicholas' church in the late 15th century,[37][29] and the medieval baptismal font now in Reculver's parish church of St Mary the Virgin at Hillborough probably came from All Saints'.[54][55][Fn 10] By 1630 there was no church: in that year, the vicar and churchwardens of St Nicholas-at-Wade reported the existence of glebe of 1.5 acres (1 ha) called "Allhallows close, in part of which antiently stood the chapel of All Saints, or Alhallows";[56] and, in 1723, antiquarian John Lewis wrote that the church was "now so entirely demolished, with all the fences around it, that there are no marks of either of them."[57]

The decline of All Saints' Church and the community of Shuart may have begun with the Black Death of 1348–9.[37][Fn 11] Further, this decline coincides with the closing of the adjacent Wantsum Channel. This channel had been a preferred route for sea-borne trade between England and continental Europe in medieval times,[59] probably providing "a large part of the early prosperity of Kent",[60] besides supporting a local industry collecting salt, but it was progressively blocked by silt.[13] While tax records of the 15th century show that the inhabitants of Shuart had then included men of the Cinque Port of Dover,[61] shipping through the Wantsum Channel had ceased by about the end of the 15th century,[13] and the northern section adjacent to Shuart was merely a creek by the middle of the 16th century.[50] The abandonment of the church presumably arose through the cost of keeping two churches – All Saints and St Nicholas – in what had become a "remote, rural parish".[37] Shuart continued to be represented in tax records in the 17th century: in 1624 it was assessed as a "vill" at the rate of £4.6s.4d (£4.32) for the archaic taxes known as "fifteenths and tenths" – this rate had been fixed in 1334, and may be compared with the rate for St Nicholas-at-Wade of £10.7s (£10.35)[62][63][Fn 12] – and Shuart appears as a borgh, or tithing, in records of the Hearth Tax for 1673.[64] However, the parish as a whole was in decline. In 1563 the parish of St Nicholas-at-Wade was the second smallest on the Isle of Thanet by number of households, having only 33, and by 1800 there were "not ... near so many".[13] By 1723 the settlement of Shuart was a matter of historical record only. John Lewis wrote then that "[it] seems as if anciently a Vill or Town belonged to [the chapel of All Saints]", and the only building recorded by Lewis was a "good farm house".[57] The farmhouse was built in the late 17th century and still stands, but otherwise today Shuart is considered a deserted medieval village.[65][66]

Excavation

The site of All Saints' Church, Shuart, was recorded on Ordnance Survey maps in the 19th century, and was confirmed in the mid-20th century through aerial photography by Kenneth St Joseph.[67][Fn 13] On the north side of a road between Shuart Farm and Nether Hale Farm, the site is on farmland now owned by St John's College, Cambridge, and was excavated with the college's permission by the Thanet Archaeological Unit between 1978 and 1979.[67][68]

The only surviving part of the main structure was its foundations of rammed chalk, which nonetheless allowed a construction history to be developed, but various elements of the structure were also found.[69][Fn 14] These included mortar flooring, glazed floor tiles, green sandstone, Caen stone, Quarr stone from the Isle of Wight and stained glass.[70] Among stone fragments were numerous carvings, including "two small delicately carved pieces of foliage which are certainly twelfth-century work".[11][71] Fragments of mortar showing the imprint of barnacles were found among the rubble in the foundation trenches, indicating that some of the stone used in the structure had been fetched from the shoreline.[31] A number of graves were also discovered, one of which had been covered by an unmarked stone, but they had been robbed and filled with rubble containing fragments of human bone.[72] Two of the graves had been dug between the demolition of the church and the construction of a smaller, short-lived replacement in the 15th century.[73] While virtually all of the building's structure had been robbed, presumably for use elsewhere, much of what remained had been destroyed by ploughing.[74]

References

Footnotes

- According to Glover 1976, the name is pronounced "Show-art", and it is given as "Shoart" in Hasted 1800b.

- The multiplication indicated would give a peasant population for the whole of the estate centred on Reculver in 1086 of 460–575 people.

- "This is an early instance of a compulsory church rate for the repair of the fabric."[42] There is no "North Street" in the vicinity today.

- Whereas Graham 1944, pp. 1 & 10, gives the population of Reculver parish during the archiepiscopacy of John Peckham (c. 1230–1292) as "over a thousand", Gough 1984, p. 19, gives it as 3,000. The relevant primary source, written in 1310 and printed at Duncombe 1784, p. 136, gives it as "trium millium vel amplius" ("three thousand or more"), and says that it continued to grow.

- In 1274–5, the jurors of Bleangate hundred in mainland Kent, in which Reculver then lay, reported that it had lately been made more difficult for the people of Thanet to reach the mainland: while previously access had been provided by a "wall", this had been cut off by a ditch dug for the abbot of St Augustine's, Canterbury.[47]

- "This was a large sum in those days, and there is room to suppose that, at that time, this [vicarage] was much better in proportion, than it is now."[48]

- Graham 1944, p. 11, gives this date as 2 September, apparently in error: see e.g. Farmer 1992, p. 327.

- For clerical tenths, see Lunt 1916.

- A facsimile of the map was published by the Ordnance Survey in 1914 and reproduced with notes in 1968; the location is marked as "All Saynts", with no reference to Shuart.[52]

- "The ancient font is of perpendicular date, and probably belonged to the church of All Saints, in Thanet, of which nothing now remains. It was rescued from a state of neglect, and kindly presented to the [new church at Hillborough in 1878] by John Rammell, Esq., of Shuart".[54]

- The population of England declined by about 40% between 1347 and 1377.[58]

- For fifteenths and tenths, see "Taxation before 1689". The National Archives. 2010. 4.2 Fifteenths and Tenths, 1334–1624. Archived from the original on 19 March 2012. Retrieved 6 June 2015.

- The site of All Saints' Church is marked on the 1877 Ordnance Survey 1:10,560 scale (6 inch/mile) County Series map of Kent, about 330 yards (302 m) east of Shuart, and land between Shuart and the church site is marked there as "Glebe". The OS grid reference is TR273679.

- An aerial photograph of the 1970s excavation, showing the foundations of rammed chalk, is at "VM_365 Day 235 The Church of All Saints Shuart". Trust for Thanet Archaeology. 2015. Archived from the original on 18 April 2015. Retrieved 18 April 2015.

Notes

- Glover 1976, p. 173.

- Historic England (2015), "Monument No. 467021", PastScape, retrieved 5 June 2015; Historic England (2015), "Monument No. 467068", PastScape, retrieved 5 June 2015; Hart, P. (2006). "Bronze Age 2000 – 700 BC". Trust for Thanet Archaeology. Archived from the original on 2 September 2013. Retrieved 5 June 2015.

- Perkins 1988.

- Historic England (2015), "Monument No. 1012305", PastScape, retrieved 5 June 2015; Historic England (2015), "Monument No. 466885", PastScape, retrieved 5 June 2015; Historic England (2015), "Monument No. 467005", PastScape, retrieved 5 June 2015; Historic England (2015), "Monument No. 467070", PastScape, retrieved 5 June 2015; Historic England (2015). "Monument No. 467076". PastScape. Retrieved 5 June 2015.

- Rollason 1982, pp. 10–1.

- Hasted 1800b, pp. 264–94.

- Yorke 1996, p. 712.

- Rollason 1982, p. 10.

- Rollason 1979, pp. 13–5; "S 8". The Electronic Sawyer. King's College London. 2015. Archived from the original on 18 May 2015. Retrieved 5 June 2015; Kelly 2008, p. 74; Jenkins 1981, p. 152.

- Rollason 1979, p. 13.

- Jenkins 1981, p. 152.

- Lewis, J. (1773). "Mappa Thaneti Insule". Wikimedia Commons. Retrieved 6 June 2015.

- Hasted 1800b, pp. 217–37.

- Gough 2014.

- Blair 2005, p. 123.

- Kelly 2008, p. 80.

- Kelly 2008, pp. 81–2.

- "S 546". The Electronic Sawyer. King's College London. 2015. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 5 June 2015.

- Kelly 2008, p. 74.

- "S 512". The Electronic Sawyer. King's College London. 2015. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 5 June 2015.

- Kelly 2008, p. 74(note).

- "S 497". The Electronic Sawyer. King's College London. 2015. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 5 June 2015.

- "S 497". The Electronic Sawyer. King's College London. 2015. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 5 June 2015; "S 512". The Electronic Sawyer. King's College London. 2015. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 5 June 2015; "S 546". The Electronic Sawyer. King's College London. 2015. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 5 June 2015; "S 1212". The Electronic Sawyer. King's College London. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 5 May 2015.

- Lewis, J. (1773). "Mappa Thaneti Insule". Wikimedia Commons. Retrieved 6 June 2015.

- Williams & Martin 2002, p. 8.

- Flight 2010, p. 162.

- Flight 2010, pp. 160, 162.

- Jenkins 1981, p. 152; Historic England (2015). "All Saints Church (466861)". PastScape. Retrieved 5 June 2015.

- Tatton-Brown 1993.

- Jenkins 1981, pp. 147–9.

- Jenkins 1981, p. 149.

- Eales 1992, p. 21.

- Jenkins 1981, pp. 149, 152.

- Jenkins 1981, pp. 149, 152 & Fig. 26.

- Jenkins 1981, p. 153 & Fig. 29.

- Jenkins 1981, pp. 149–50, 153 & Fig. 29.

- Jenkins 1981, p. 154.

- "VM_365 Day 38 Medieval Floor Tiles". Trust for Thanet Archaeology. 2014. Archived from the original on 18 April 2015. Retrieved 18 April 2015.

- Gough 1984, p. 19.

- Graham 1944, p. 2.

- Graham 1944, pp. 2–3.

- Graham 1944, p. 3.

- Gough 1992, pp. 91–2.

- Graham 1944, pp. 10–1.

- Graham 1944, p. 10.

- Hasted 1800a, pp. 237–53.

- Jones 2007, pp. 1–2.

- Lewis 1723, p. 30.

- Graham 1944, p. 11.

- Hearne 1711, p. 137.

- Bagshaw 1847, p. 181.

- Symonson, P. (n.d.). "A New Description of Kent Divided into the fyve Lathes". British Library. Retrieved 13 December 2016.

- Jenkins 1981, pp. 153–4.

- "Reculver. Dedication of the new church". Whitstable Times and Herne Bay Herald. 22 June 1878. Retrieved 7 May 2014 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- Exploring Kent's Past (n.d.). "Parish church of St Mary the Virgin, Hillborough". Kent County Council. Archived from the original on 20 May 2015. Retrieved 5 June 2015.

- Hasted 1800b, pp. 237–53.

- Lewis 1723, p. 33.

- Russell 1966, pp. 16–7.

- Kelly 2008, p. 72.

- Kelly 1992, p. 9.

- "E179/227/103". The National Archives. n.d. Retrieved 6 June 2015.

- Lambarde 1596, p. 25.

- "E179/127/582". The National Archives. Retrieved 6 June 2015.

- "E179/129/746". The National Archives. n.d. Retrieved 6 June 2015.

- Newman 1983, p. 439.

- Historic England (2012). "Monument No. 467017". PastScape. Retrieved 6 June 2015.

- Jenkins 1981, p. 147.

- "VM_365 Day 235 The Church of All Saints Shuart". Trust for Thanet Archaeology. 2015. Archived from the original on 18 April 2015. Retrieved 18 April 2015.

- Jenkins 1981, pp. 147–50.

- Jenkins 1981, pp. 149–54.

- "VM_365 Day 133 Decorative Stone from lost Medieval Parish Church of All Saints, Shuart". Trust for Thanet Archaeology. 2014. Archived from the original on 18 April 2015. Retrieved 18 April 2015.

- Jenkins 1981, pp. 149–50.

- Jenkins 1981, pp. 150, 154.

- Jenkins 1981, pp. 149–50, 154.

Bibliography

- Bagshaw, S. (1847), History, Gazetteer & Directory of Kent, Bagshaw

- Blair, J. (2005), The Church in Anglo-Saxon Society, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-822695-6

- Duncombe, J. (1784), "The history and antiquities of the two parishes of Reculver and Herne, in the county of Kent", in Nichols, J. (ed.), Bibliotheca Topographica Britannica, 18, Nichols, pp. 65–161, OCLC 475730544

- Eales, R. (1992), "An introduction to the Kent Domesday", in Eales, R.; Thorn, F. (eds.), The Kent Domesday, Alecto, pp. 1–49, ISBN 0-948459-98-0

- Farmer, D.H. (1992), The Oxford Dictionary of Saints (3rd ed.), Oxford University Press, p. 327, ISBN 0-19-283069-4

- Flight, C. (2010), The Survey of Kent: Documents Relating to the Survey of the County Conducted in 1086, BAR British Series, 506, Archaeopress, ISBN 978-1-4073-0541-7, archived from the original on 14 May 2014, retrieved 6 June 2015

- Glover, J. (1976), The Place Names of Kent, Batsford, ISBN 978-0-7134-3069-1

- Gough, H. (1984), "The cure of souls at Hoath", in McIntosh, K.H.; Gough, H.E. (eds.), Hoath and Herne: The Last of the Forest, K. H. McIntosh, pp. 19–23, ISBN 978-0-95024-237-8

- Gough, H. (1992), "Eadred's charter of AD 949 and the extent of the monastic estate at Reculver, Kent", in Ramsay, N.; Sparks, M.; Tatton-Brown, T. (eds.), St Dunstan: His Life, Times and Cult, Boydell, pp. 89–102, ISBN 978-0-85115-301-8

- Gough, H. (2014), "The two names of a Reculver inn", Kent Archaeological Review (195): 186–91, ISSN 0023-0014

- Graham, R. (1944), "Sidelights on the rectors and parishioners of Reculver from the register of Archbishop Winchelsey", Archaeologia Cantiana, Kent Archaeological Society, 57: 1–12, ISSN 0066-5894, archived from the original on 10 February 2012, retrieved 6 June 2015

- Hasted, E. (1800a), The History and Topographical Survey of the County of Kent, 9, Bristow, OCLC 5072512, archived from the original on 17 May 2015, retrieved 6 May 2015

- Hasted, E. (1800b), The History and Topographical Survey of the County of Kent, 10, Bristow, OCLC 5072512, archived from the original on 6 June 2015, retrieved 6 June 2015

- Hearne, T. (1711) [1700], The Itinerary of John Leland the Antiquary (PDF), 6, OCLC 4412199, archived (PDF) from the original on 15 April 2012, retrieved 6 June 2015

- Jenkins, F. (1981), "The church of All Saints, Shuart in the Isle of Thanet", in Detsicas, A. (ed.), Collectanea Historica: Essays in Memory of Stuart Rigold, Kent Archaeological Society, pp. 147–54, ISBN 0-906746-02-7

- Jones, B. (2007), Kent Hundred Rolls (PDF), Kent Archaeological Society, archived (PDF) from the original on 29 October 2013, retrieved 23 May 2014

- Kelly, S. (2008), "Reculver Minster and its early charters", in Barrow, J.; Wareham, A. (eds.), Myth, Rulership, Church and Charters Essays in Honour of Nicholas Brooks, Ashgate, pp. 67–82, ISBN 978-0-7546-5120-8

- Kelly, S. (1992), "Trading privileges from eighth-century England", Early Medieval Europe, 1 (1): 3–28, doi:10.1111/j.1468-0254.1992.tb00002.x, ISSN 1468-0254

- Lambarde, W. (1596) [1576], A Perambulation of Kent: Conteining the Description, Hystorie, and Customes of that Shyre, Bollisant, OCLC 65329201

- Lewis, J. (1723), The History and Antiquities Ecclesiastical and Civil of the Isle of Tenet in Kent, OCLC 13116471

- Lunt, W.E. (1916), "Collectors' accounts for the clerical tenth levied in England by order of Nicholas IV", English Historical Review, 31 (121): 102–19, ISSN 0013-8266

- Newman, J. (1983), North East and East Kent, Pevsner Architectural Guides: Buildings of England (3rd ed.), Yale University Press, ISBN 0-300-09613-5

- Perkins, D.R.J. (1988), "A Late Bronze Age hoard from Shuart" (PDF), Archaeologia Cantiana, 106: 201–4, ISSN 0066-5894, archived (PDF) from the original on 5 June 2015, retrieved 5 June 2015

- Rollason, D.W. (1979), "The date of the parish boundary of Minster-in-Thanet (Kent)", Archaeologia Cantiana, Kent Archaeological Society, 95: 7–17, ISSN 0066-5894

- Rollason, D.W. (1982), The Mildrith Legend: A Study in Early Medieval Hagiography in England, Leicester University Press, ISBN 0-7185-1201-4

- Russell, J.C. (1966), "The preplague population of England", Journal of British Studies, 5 (2): 1–21, ISSN 1545-6986

- Tatton-Brown, T. (1993), "St Nicholas Church, St Nicholas at Wade TR 265 667", Canterbury Diocese: Historical and Archaeological Survey, Kent Archaeological Society

- Williams, A.; Martin, G.H., eds. (2002) [1992], Domesday Book A Complete Translation, Penguin, ISBN 0-14-051535-6

- Yorke, B. (1996), "Charters of St Augustine's Abbey, Canterbury, and Minster-in-Thanet. Edited by Susan Kelly", Journal of Ecclesiastical History, 7 (4): 712, ISSN 1469-7637