Lancetfish

Lancetfishes are large oceanic predatory fishes in the genus Alepisaurus ("scaleless lizard") in the monotypic family Alepisauridae.[2]

| Lancetfishes | |

|---|---|

| |

| Longnose lancetfish, Alepisaurus ferox | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Phylum: | |

| Class: | |

| Order: | |

| Family: | Alepisauridae Swainson, 1839 |

| Genus: | Alepisaurus R. T. Lowe, 1833 |

Lancetfishes grow up to 2 m (6.6 ft) in length. Very little is known about their biology, though they are widely distributed in all oceans, except the polar seas.[3] Specimens have been recorded as far north as Greenland.[4] They are often caught as bycatch for vessels long-lining for tuna.

The generic name is from Greek a- meaning "without", lepis meaning "scale", and sauros meaning "lizard".

Species

The two currently recognized extant species in this genus are:[5]

- Alepisaurus brevirostris Gibbs, 1960 (short-snouted lancetfish)

- Alepisaurus ferox R. T. Lowe, 1833 (long-snouted lancetfish)

The main difference between the two is the shape of the snout, which is long and pointed in A. ferox, and slightly shorter in A. brevirostris. A third recognized species, A. paronai D'Erasmo, 1923,[6] is a fossil known from Middle Miocene-aged strata from Italy.

Description

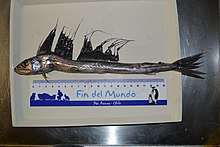

Lancetfish possess a long and very high dorsal fin, soft-rayed from end to end, with an adipose fin behind it. The dorsal fin has 41 to 44 rays and occupies the greater length of the back. This fin is rounded in outline, about twice as high as the fish is deep, and can be depressed into a groove along the back. The body is slender, flattened from side to side, deepest at the gill covers, and tapers back to a slender caudal peduncle.

The mouth is wide, gaping to the back of the eye, and each jaw has two or three large, fang-like teeth, in addition to numerous smaller teeth. The caudal fin is very deeply forked; its upper lobe is prolonged as a long filament, although most lancetfishes seem to lose this when captured. The anal fin originates under the last dorsal ray, and is deeply concave in outline. The ventral fins are about halfway between the anal fin and the tip of the snout, while the pectoral fins are considerably longer than the body is deep and are situated very low down on the sides. No scales are present, and the fins are very fragile.

Lancetfishes are among the largest living bathypelagic fish forms. Specimens have been collected in excess of 2,080 mm (6.82 ft) in length, often from dead individuals that drifted ashore. Like their close relatives in the Aulopiformes suborder Alepisauroidei, lancetfish lack swimbladders and are simultaneous hermaphrodites.[7]

Ecology and life history

Lancetfish have large mouths and sharp teeth, indicating a predatory mode of life. Their watery muscle is not suited to fast swimming and long pursuit, so they likely are ambush predators, using their narrow body profile and silvery coloration to conceal their presence. Lancetfish float in the water column, using their large eyes to scan for prey, which once detected, they attack using their forked tails for rapid bursts of speed, their large dorsal sails are likely used to maintain a stable trajectory toward their target, and their large mouths and teeth are used to subdue prey before it can escape. They are voracious predators and their distensible stomachs have often been found to contain a variety of food, mainly fishes, octopods, squid, tunicates, and crustacea.[7]

Extremely little is known of lancetfish reproductive habits. While they are known to be simultaneous hermaphrodites, spawning has never been observed. They likely are planktonic spawners from the small size and pelagic transmission of their larva. While seasonal presences and absences of lancetfish capture have been noted in certain ocean basins, if spawning is a seasonal occurrence remains unclear.

No commercial fisheries exist for lancetfishes. Their flesh is watery and gelatinous, although edible and reportedly sweet to taste. They are caught as bycatch by tuna fisheries and are often considered pests, taking bait intended for more valuable species.

Lancetfishes have been caught on longlines as shallow as ten fathoms in Oregon and the Gulf of Mexico. Some anecdotal reports have observed shoals of 30 - 40 individuals at the surface in Icelandic waters during spring. Hook and line capture of lancetfish from surf zones is not unheard of and dietary surveys suggest at least some feeding occurs within inshore waters. However, lancetfish are generally considered solitary, mesopelagic, and bathypelagic fishes occupying depths between 100 and 2000 m. While they have not been shown to participate in diel vertical migration, they have been found in a huge variety of depths.[7]

The tetraphyllidean tapeworm Pelichnibothrium speciosum is a significant parasite of long-snouted lancetfish. The species seems to be an intermediate or paratenic host for the tapeworm.[8]

The large size, wide depth distribution, and opportunistic diet of lancetfish have lent them to the study of other pelagic biodiversity because their voraciousness can be used to survey smaller organisms throughout the deep-sea that are difficult to capture by other means.[9] Adult lancetfish are commonly caught as bycatch in longline fisheries and analysis of their gut contents provides a convenient, if somewhat biased, method for surveying regional pelagic biodiversity, so much so that some species of deep-sea fishes were first described from specimens found in the stomachs of lancetfish. This may be partially due to the unusually slow rate of digestion apparent in lancetfish, where actual digestion seemingly does not begin in earnest until the beginning of the small intestines.[7][10][9][11]

In addition to a high degree of cannibalism and consumption of gelatinous foods, lancetfishes have also been documented with plastic refuse in their stomachs in the tropical north Pacific.[9] While the exact pathway of this ingestion is not yet clear, lancetfish likely have some affinity with the epipelagic, but this could be by way of direct migration or migration of prey which had eaten plastic at the surface and returned to depth. One particularly bizarre example of this affinity for surface waters comes from a gut survey of lancetfish in the Indian Ocean where a large amount (24.1%) of floating macroalgae was documented in the stomachs of exclusively adult (>100 cm) individuals. This is most likely indicative of the pursuit of evasive prey-types by larger lancetfish into epipelagic refuges.[12] The voracious appetite, low degree of prey selectivity, broad depth distribution, slow rate of digestion and ease of sampling via longline bycatch make lancetfishes useful platforms by which to study the greater ecology of deep mid-water fauna.[12] [9]

References

- Sepkoski, J. (2002). "A compendium of fossil marine animal genera". Bulletins of American Paleontology. 364. Archived from the original on 2011-07-23. Retrieved 2008-01-08.

- Froese, Rainer, and Daniel Pauly, eds. (2006). "Alepisauridae" in FishBase. February 2006 version.

- Kubota, T.; Uyeno, T. (1978). "On some meristic characters of lancetfish, Alepisaurus, collected from Suruga Bay, Japan". Journal of Faculty of Marine Science and Technology, Tokai University. 11: 63–69.

- Jensen, A. S. (1948). Contributions to the Ichthyofauna of Greenland. Skrifter Univ. Zool. Mus. Københaven. 9. pp. 1–182. OCLC 83357750.

- Froese, Rainer and Pauly, Daniel, eds. (2012). Species of Alepisaurus in FishBase. February 2012 version.

- Uyeno, Teruya. "A Miocene alepisauroid fish of a new family, Polymerichthyidae, from Japan." Bull. Nat. Sci. Mus 10 (1967): 383-394.

- Rofen R.R. (1966). Olsen, Y.H. & Atz, J.W. (eds.). Fishes of the Western North Atlantic Number 1. Part 5. New Haven: Yale University. pp. 482–497.

- Scholz, T.; Euzet, L.; Moravec, F. (1998). "Taxonomic status of Pelichnibothrium speciosum Monticelli, 1889 (Cestoda: Tetraphyllidea), a mysterious parasite of Alepisaurus ferox Lowe (Teleostei: Alepisauridae) and Prionace glauca (L.) (Euselachii: Carcharinidae)". Systematic Parasitology. 41 (1): 1–8. doi:10.1023/A:1006091102174.

- Choy, C.A.; Portner, E.; Iwane, M.; Drazen, J.C. (2013). "Diets of five important predatory mesopelagic fishes of the central North Pacific". Mar Ecol Prog Ser. 492: 169–184. doi:10.3354/meps10518.

- Romanov, E.V.; Ménard, F.; Zamorov, V.V.; Potier, M. (2008). "Variability in conspecific predation among longnose lancetfish Alepisaurus ferox in the western Indian Ocean". Fisheries Science. 74 (1): 62–68. doi:10.1111/j.1444-2906.2007.01496.x.

- Haedrich, R.L.; Nielsen, J.G. (1966). "Fishes eaten by Alepisaurus (Pisces, Iniomi) in the southeastern Pacific Ocean". Deep-Sea Res. 13: 909–919.

- Romanov, E.V.; Zamorov, V.V. (2007). "Regional feeding patterns of the longnose lancetfish (Alepisaurus ferox Lowe, 1833) of the western Indian Ocean". Western Indian Ocean J. Mar. Sci. 6: 37–56.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Alepisauridae. |