Rifa'a al-Tahtawi

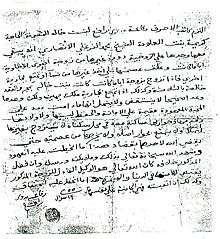

Rifa'a al-Tahtawi (also spelt Tahtawy; Arabic: رفاعة رافع الطهطاوي, ALA-LC: Rifā‘ah Rāfi‘ al-Ṭahṭāwī; 1801–1873) was an Egyptian writer, teacher, translator, Egyptologist and renaissance intellectual. Tahtawi was among the first Egyptian scholars to write about Western cultures in an attempt to bring about a reconciliation and an understanding between Islamic and Christian civilizations. He founded the School of Languages in 1835 and was influential in the development of science, law, literature and Egyptology in 19th-century Egypt. His work influenced that of many later scholars including Muhammad Abduh.

Rifa'a al-Tahtawi | |

|---|---|

Rifa'a al-Tahtawy, 1801–1873. | |

| Born | October 15, 1801 |

| Died | May 27, 1873 (aged 71) |

Background

Tahtawi was born in 1801 in the village of Tahta, Sohag, the same year the French troops evacuated Egypt. He was an Azharite recommended by his teacher and mentor Hasan al-Attar to be the chaplain of a group of students Mohammed Ali was sending to Paris in 1826. Originally intended to be an Imam, or Islamic "religious guide", he was allowed to associate with the other members of the mission through persuasion of his authoritative figures.[1] Many student missions from Egypt went to Europe in the early 19th century to study arts and sciences at European universities and acquire technical skills such as printing, shipbuilding and modern military techniques. According to his memoir Rihla (Journey to Paris), Tahtawi studied ethics, social and political philosophy, and mathematics and geometry. He read works by Condillac, Voltaire, Rousseau, Montesquieu and Bézout among others during his séjour in France.[2]

In 1831, Tahtawi returned home to be part of the statewide effort to modernize the Egyptian infrastructure and education. He undertook a career in writing and translation, and founded the School of Languages (also knowns as School of Translators) in 1835, which become part of Ain Shams University in 1973.[3] The School of Languages graduated the earliest modern Egyptian intellectual milieu, which formed the basis of the emerging grassroots mobilization against British colonialism in Egypt. Three of his published volumes were works of political and moral philosophy. They introduced his Egyptian audience to Enlightenment ideas such as secular authority and political rights and liberty; his ideas regarding how a modern civilized society ought to be and what constituted by extension a civilized or "good Egyptian"; and his ideas on public interest and public good.[4] Tahtawi's work was the first effort in what became an Egyptian renaissance (nahda) that flourished in the years between 1860–1940.[5]

He died in Cairo in 1873.

Muslim Modernity

Tahtawi is considered one of the early adapters to Islamic Modernism. Islamic Modernists attempted to integrate Islamic principles with European social theories. In 1826, Al-Tahtawi was sent to Paris by Mehmet Ali. Tahtawi studied at an educational mission for five years, returning in 1831. Tahtawi was appointed director of the School of Languages. At the school, he worked translating European books into Arabic. Tahtawi was instrumental in translating military manuals, geography, and European history.[6] In total, al-Tahtawi supervised the translation of over 2,000 foreign works into Arabic. Al-Tahtawi even made favorable comments about French society in some of his books.[7] Tahtawi stressed that the Principles of Islam are compatible with those of European Modernity.

In his piece, The Extraction of Gold or an Overview of Paris, Tahtawi discusses the patriotic responsibility of citizenship. Tahtawi uses Roman civilization as an example for what could become of Islamic civilizations. At one point all Romans are united under one Caesar but split into East and West. After splitting, the two nations see “all its wars ended in defeat, and it retreated from a perfect existence to nonexistence.” Tahtawi understands that if Egypt is unable to remain united, it could fall prey to outside invaders. Tahtawi stresses the importance of citizens defending the patriotic duty of their country. One way to protect one's country according to Tahtawi, is to accept the changes that come with a modern society.[8]

Al-Tahtawi, like others of what is often referred to as the 'Nahda' (Muslim Nahda), was spellbound and "seduced" by French (and Western in general) culture in his books. Shaden Tageldin has suggested that this produced an intellectual inferiority complex in his ideas that aided in an "intellectual colonization" that remains till today among Egyptian intelligentsia.[9]

Work

A selection of his works are:

Tahtawi's writings

- A Paris Profile, written during Tahtawi's stay in France.

- The methodology of Egyptians minds with regard to the marvels of modern literature, published in 1869 crystallizing Tahtawi's opinions on modernization.

- The honest guide for education of girls and boys, published in 1873 and reflecting the main precepts of Tahtawi's educational thoughts.

- Tawfik al-Galil insights into Egypt's and Ismail descendants' history, the first part of the History Encyclopedia published in 1868 and tracing the history of ancient Egypt till the dawn of Islam.

- A thorough summary of the biography of Mohammed published after Tahtawi's death, recording a comprehensive account of the life of Prophet Mohammed and the political, legal and administrative foundations of the first Islamic state.

- Towards a simpler Arabic grammar, published in 1869.

- Grammatical sentences, published in 1863.

- Egyptian patriotic lyrics, written in praise of Khedive Said and published in 1855.

- The luminous stars in the moonlit nights of al-Aziz, a collection of congratulatory writings to some princes, published in 1872.

Tahtawi's translations

- The history of ancient Egyptians, published in 1838.[10]

- The Arabization of trade law, published in 1868.[10]

- The Arabization of the French civil law, published in 1866.[10]

- The unequivocal Arabization approach to geography, published in 1835.[10]

- Small-scale geography, published in 1830.[10]

- Metals and their use, published in 1867.[10]

- Ancient philosophers, published in 1836.[10]

- Principals of engineering, published in 1854.[10]

- Useful metals, published in 1832.[10]

- Logic, published in 1838.[10]

- Sasure's engineering, published in 1874.[10]

- General geography.[10]

- The French constitution.[10]

- On health policies.[10]

- On Greek mythology.[10]

Notes

- Cleveland, William L., Bunton, Martin: A History of the Modern Middle East, Westview Press, 2013, pp. 86.

- Vatikiotis, p. 113

- Faculty of Al-Alsun: Historical background

- Vatikiotis, p. 115–116

- Vatikiotis, p. 116

- Gelvin, 133-134

- Cleveland, William L. (2008)"History of the Modern Middle East" (4th ed.) pg.93.

- Galvin 160-161

- Tageldin, Shaden. (2011). Disarming Words: Empire and the Seductions of Translation in Egypt. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Source: Egyptian State Information Service

Further reading

- Newman, Daniel (2004). An Imam in Paris: Al-Tahtawi's Visit to France (1826–31), London: Saqi Books. ISBN 978-0-86356-346-1

- Wael Abu-'Uksa (2016). Freedom in the Arab World: Concepts and Ideologies in Arabic Thought in the Nineteenth Century. Cambridge University Press.

References

- Reid, Donald Malcolm (2002). Whose Pharaohs? Archaeology, Museums, and Egyptian National Identity from Napoleon to World War I. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0520240698.

- Vatikiotis, P. J. (1976). The Modern History of Egypt (Repr. ed.). ISBN 978-0297772620.

- Gelvin, James L. (2005). The Modern Middle East: a History. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0195167894.

External links

| Arabic Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Rifa'a el-Tahtawi. |

- Gran, Peter. Tahtawi in Paris. Ahram Weekly. 10–16 January 2002.

- refaa el tahtawi