Action of 26 July 1806

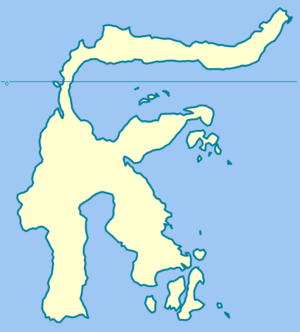

The Action of 26 July 1806 was a minor naval engagement of the Napoleonic Wars fought off the southern coast of the island of Celebes in the Dutch East Indies. During the battle, a small British squadron attacked and defeated a Dutch force defending a valuable convoy, which was also captured. The British force—consisting of the frigate HMS Greyhound and brig-sloop HMS Harrier under the command of Captain Edward Elphinstone—was initially wary of the Dutch, mistaking the Dutch East Indiaman merchant ship Victoria for a ship of the line. Closer observation revealed the identity of the Dutch vessels the following day and Elphinstone led his frigate against the leading Dutch warship Pallas while Harrier engaged the merchant vessels and forced them to surrender. Only the corvette William escaped, taking no part in the engagement.

The battle was the first in a series of actions by the Royal Navy squadron based at Madras with the intention of eliminating the Dutch squadron maintained at Java. Greyhound had been sent to the Java Sea and the Molucca Islands to reconnoitre the Dutch ports in preparation for a raid on Java by a larger force under Rear-Admiral Sir Edward Pellew later in the year. Elphinstone's success was followed by a second frigate action by Captain Peter Rainier in which the Dutch ship Maria Riggersbergen was captured. In November 1806, Admiral Pellew led the main body of his squadron against the capital of the Dutch East Indies at Batavia and a year later eliminated the last vessels of the Dutch East Indies squadron at Griessie.

Background

The Dutch squadron in the Dutch East Indies was a constant threat to the British system of trade routes during the Napoleonic Wars. The Dutch—under the guise of the Kingdom of Holland and ruled by the French Emperor Napoleon's brother Louis Bonaparte—had joined the war against Britain following the end of the Peace of Amiens in 1803. Although the primary function of the Dutch East Indies squadron was the suppression of piracy, their presence threatened British shipping in the Malacca Straits, in particular the lucrative trade with China.[1] At the start of every year, the "China Fleet"—a large convoy of British East Indiamen merchant ships—sailed from Canton and passed through the South China Sea and the Malacca Strait on their journey to the Indian Ocean and eventually to Britain. Worth millions of pounds, these convoys were vital to the British economy, but they faced considerable danger in passing through waters that were within easy reach of the Dutch ports in Java.[2]

In 1804, a French squadron under Rear-Admiral Charles Linois used Batavia on Java as a base to attack the China Fleet, although the attempt ended in failure at the Battle of Pulo Aura.[2] Java presented a clear threat to British maritime interests in the South China Sea, but the British squadron based in the Indian Ocean was too weak in 1805 to consider operations so far from its main base at Madras while Linois remained active. By the start of 1806, Linois had sailed into the Atlantic and an expeditionary force had seized the Dutch base at the Cape of Good Hope, securing the western Indian Ocean and providing reinforcements that allowed Rear-Admiral Sir Edward Pellew to begin operations against the Dutch forces in the East Indies.[1]

Pellew's first action, during the spring of 1806, was to deploy several frigates to the Java Sea with instructions to reconnoitre the Dutch squadron and its main port at Batavia. The first British ship to reach the Java Sea was the 32-gun frigate HMS Greyhound under Captain Edward Elphinstone, which arrived in July 1806. In company with the brig-sloop HMS Harrier under Commander Edward Troubridge, the two vessels cruised in search of Dutch activity in the area. On 4 June they successfully destroyed the armed brig Christian Elizabeth at Manado and two days later captured the Belgica at Tidore.[3]

During the evening of 25 July, lookouts spotted four sails passing through the Selayar Strait that separates Selayar Island from the southern tip of Celebes. These four vessels were a Dutch convoy from the Molucca Islands, consisting of: The Dutch national frigate Pallas, of 36 guns, under Captain N. S. Aalbers; Dutch East India Company corvette William, of twenty 24-pounder guns and 110 men, under Captain P. Feteris; Dutch East Indiaman Victoria (or in some sources Vittoria), of about 800 tons burthen (bm), under Captain Klaas Kenkin and Dutch East Indiaman Batavier, of some 500 tons (bm) under Captain William De Val.[3][4]

Battle

On observing the Dutch ships, Elphinstone immediately gave chase. Aalbers responded by forming his ships in a line of battle and retaining close formation as the convoy passed the Celebes coast close to the small Dutch trading posts at Borthean and Balacomba.[4] At 21:00, Aalbers ordered his force to anchor 7 nmi (8.1 mi; 13 km) offshore and prepare for the British attack. Elphinstone was cautious however as Victoria was a particularly large ship, with two decks and the appearance of a ship of the line. Aware that such a large vessel could easily destroy his frigate Elphinstone halted his advance and Greyhound and Harrier stopped to observe the Dutch convoy during the night, maintaining a position 2 nmi (2.3 mi; 3.7 km) to windward of Aalbers' force.[3]

At dawn, lookouts on Greyhound were able to establish that Victoria was a large merchant ship rather than a warship and Elphinstone was encouraged to resume the attack. Aalbers sailed shortly afterwards, his ships tacking away from the shore in line of battle ready for the British advance. In doing so, Pallas drew ahead of the next ship in line, creating a gap through which the British attack could be directed.[3] At 05:00, Elphinstone raised French colours in an effort to confuse the Dutch officers and indicated that he wished to speak with the Dutch commander. Aalbers was not fooled, and when Elphinstone opened fire on Pallas at close range at 05:30, the Dutch frigate replied immediately. With the frigates engaged, Harrier cut between Pallas and Victoria, Troubridge discharging his carronades into Victoria and ordering his crew to fire muskets at the deck of Pallas. In response, Victoria and Batavier pulled out of the line to engage Harrier, which continued its fire against Pallas, while William, bringing up the rear of the Dutch line, pulled out completely and sailed for the coast.[5]

Elphinstone rapidly took advantage of the confusion Harrier's attack had created, passing Aalbers' bow and raking his ship. Elphinstone then threw his sails back, halting his ship and allowing Greyhound to maintain a position across Pallas' bow from which he could inflict severe damage on the Dutch frigate without coming under fire himself.[6] As the damage and casualties mounted on Pallas, Harrier joined the attack. Gunfire from the Dutch ship gradually slackened, and finally stopped at 06:10, the Dutch flag was struck from the mast and Pallas surrendered with over 40 casualties from a crew of 250 (including 50 local recruits).[7] Throughout the engagement, Victoria and Batavier had kept up a constant but inefficient fire on Harrier, Troubridge waiting until the Dutch flagship surrendered before counterattacking.[6]

With Troubridge in pursuit, the Dutch merchant ships were unable to escape Harrier, and at 06:30 Victoria surrendered. Sending a boat to take possession, Troubridge immediately turned away towards Batavier. Elphinstone too was sailing towards the isolated merchant vessel and at 06:40 Captain De Val surrendered rather than fight the superior British force.[6] William successfully escaped in the aftermath of the battle, rapidly outdistancing a weak chase from the battered Harrier. All three captured ships were taken over by prize crews and brought to Port Cornwallis on South Andaman Island. Casualties on Pallas were heavy, with eight men killed outright and 32 wounded, including Aalbers and three of his lieutenants. Six of the wounded later died, including the Dutch captain. There were also four men killed on the East Indiamen and seven wounded, one of whom died later. British losses by contrast were light, with one man killed and eight wounded on Greyhound and just three wounded on Harrier.[8]

Aftermath

The prizes were sold in India. The Royal Navy took Pallas into service as HMS Celebes.[9] However, it sold her in 1807.[10]

Elphinstone did not long survive his victory: he was ordered back to Britain in early 1807 and took passage on Rear-Admiral Sir Thomas Troubridge's flagship HMS Blenheim. He was presumed drowned in February 1807 along with the entire crew, when Blenheim disappeared during a hurricane in the western Indian Ocean.[7]

For Pellew, the victory was an encouraging sign of the weakness of the Dutch squadron. In October, Captain Peter Rainier seized another Dutch frigate from Batavia harbour itself and the following month Admiral Pellew led a large scale raid on the port that eliminated most of the Dutch East Indies squadron. Two ships of the line escaped Pellew's attack, but they were old and in a poor state of repair, and so were unable to defend themselves when Pellew discovered and destroyed them at Griessie in 1807.[11]

Citations

- Gardiner, p. 81

- Clowes, p. 336

- "No. 16016". The London Gazette. 4 April 1807. p. 422.

- James, p. 251

- Clowes, p. 387

- James, p. 252

- Clowes, p. 386

- "No. 16016". The London Gazette. 4 April 1807. p. 423.

- Clowes, p. 564.

- Winfield (2008), p.215.

- Gardiner, p. 82

References

- Clowes, William Laird (1997) [1900]. The Royal Navy, A History from the Earliest Times to 1900, Volume V. Chatham Publishing. ISBN 1-86176-014-0.

- Gardiner, Robert, ed. (2001) [1998]. The Victory of Seapower. Caxton Editions. ISBN 1-84067-359-1.

- James, William (2002) [1827]. The Naval History of Great Britain, Volume 4, 1805–1807. Conway Maritime Press. ISBN 0-85177-908-5.

- Winfield, Rif (2008). British Warships in the Age of Sail 1793–1817: Design, Construction, Careers and Fates. Seaforth. ISBN 1-86176-246-1.