Acontheus

Acontheus is a genus belonging to the well-known extinct class of fossil marine arthropods, the trilobites. It lived during the Cambrian Period,[1] which lasted from 541 (± 1.0) to 485.4 (± 1.7) million years ago. The genus is geographically widespread having been recorded from middle Cambrian strata in Sweden, Newfoundland, Germany, Siberia, Antarctica, Queensland, China and Wales.

| Acontheus | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Class: | †Trilobita |

| Order: | †Corynexochida |

| Family: | †Corynexochidae |

| Subfamily: | †Acontheinae |

| Genus: | †Acontheus Angelin, 1851 |

Acontheus appears confined to the Drumian and Guzhangian Stages, uppermost two of three Stages subdividing the middle Cambrian Miaolingian Series and, if species assignments are correct, the genus ranges in terms of the Scandinavian sequence from at least the Hypagnostus parvifrons Biozone in Wales to the Lejopyge laevigata Biozone at various locations elsewhere.

Taxonomy

Phylum ARTHROPODA von Siebold, 1848.

Class TRILOBITA Walch, 1771.

Order CORYNEXOCHIDA Kobayashi, 1935.[2]

Family CORYNEXOCHIDAE Angelin, 1854.[3]

Subfamily ACONTHEINAE Westergård, 1950.[4]

Genus Acontheus Angelin, 1851.[5]

Description

Subfamily ACONTHEINAE Westergärd, 1950, emend. Geyer, 1994 [6], [=TRINIIDAE Poletaeva, 1956, p. 17 [7]; TRINIINAE Suvorova, 1964, p. 227; CORYNEXOCHELLINAE Suvorova, 1964, p. 229;[8]; ABAKANIINAE Romanenko, in Repina et al., 1999, p. 17 [9]] (See Cotton, 2001, p.194). [10]

Cotton (op. cit.) also erected Tribe HARTSHILLINI within the Acontheinae to accommodate the highly derived genera Hartshillia Illing, 1916 [11] and Hartshillina Lake, 1940. [12]

Öpik (1982, p.77) [13] placed Acontheinae in the Dolichometopidae “by virtue of the similarities in pygidial structure between Fuchouia (Dolichometopidae) and Acontheus tenebrarum” and concluded that “at all events the absence of eyes in Acontheus justifies an independent status for its subfamily”.

Diagnosis:

Small heteropygous Corynexochidae, either lacking eyes and dorsal sutures or, with proparian sutures and small palpepral lobes (contrast Westergärd, 1950, p.9; Hutchinson, 1962, p.109, Pl. 16, figures 8a-b, 9; Jago et al., 2011, p.29). Cephalon slightly parabolic in outline with rounded or acute genal angles; genae convex, subcircular to subtriangular in outline; lateral borders wide. Cephalic exoskeleton punctate or smooth. Thorax of 6 segments in species illustrated; pleurae bent strongly downwards abaxially, tips sharply rounded; pleural furrows straight, linked to posterior corners of axial rings by shallower oblique furrows. Axial furrows indistinctly defined. Pygidial axis composed of three (or four?) rings and a terminal piece. Pleural fields usually separated by axis; four pairs of pleural or interpleural furrows extend to margin; border broad with uniform convexities; margin entire.

Genus Acontheus Angelin, 1851 [= Aneucanthus Angelin 1854 (Obj.); Aneuacanthus Barrande, 1856 (Obj.)].[14]

Characteristics of Acontheus are as for the subfamily.

Type species: By monotypy, A. acutangulus Angelin, 1851, from the Zone of Solenopleura s.l. brachymetopa (Andrarum Limestone), Andrarum, Scania (redescribed by Westergård, 1950, p.9, pl.18, figs.4-6).

Other species:

Acontheus cf. acutangulus, from the Guzhangian (probably lower Lejopyge laevigata Zone), Northern Victoria Land, Antarctica (Jago et al. 2011). [15]

Acontheus inarmatus, from the Paradoxides davidis Zone, southeastern Newfoundland (Hutchinson, 1962). [16]

Acontheus inarmatus minutus, from the Drumian Stage, Franconian Forest (German: Frankenwald), Germany. (Sdzuy, 2000; Geyer, 2010). [17]; [18]

Acontheus patens, from the late middle Cambrian of Siberia (Lazarenko, 1965). [19]

Acontheus burkeanus, from the Lejopyge laevigata I Zone of Queensland, Australia (Öpik, 1961). [20]

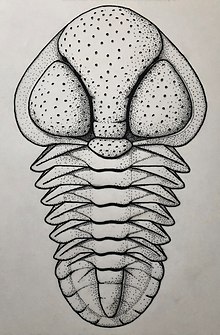

Acontheus sp. nov. (see figure above), from the Hypagnostus parvifrons Zone (Menevia Formation [21]) of Porth-y-rhaw, St. David's, Wales. (Listed by Cotton, 2001, Tables 1 & 2 and Text Figs. 2 & 3; also recorded from Locs. PR-4 & PR-13 of Rees et al., 2014, pp. 26, 27).

Acontheus tenebrarum, Öpik (1982, pl. 32, fig. 5) has been excluded from the genus (Jago et al., 2011).

Acontheus limbatus, Egorova 1982 (in Egorova et al., 1982 [22]) is also exluded and has been reallocated to Clavigellus (Type species, C. annulus, Geyer (1994, p.1314, fig. 6).

Remarks:

Hutchinson (1962, p.109) noted that the ‘cranidium’ of A. inarmatus resembles that of the much larger Acontheus acutangulus Angelin, but differs in that the glabella is more strongly expanded frontally, glabellar furrows are weaker, genal spines are lacking (unless a marginal suture had removed the posterolateral border with genal spine) and the glabella and cheeks are punctate rather than smooth. He also credibly remarked that “according to modern usage, these differences are great enough to warrant generic distinction between the two forms” but nevertheless preferred to retain them in the same genus.

The cephalon of Acontheus sp. nov. particularly resembles that of A. inarmatus, but differs in having larger genae and the glabella less expanded frontally; in A. inarmatus the maximum glabellar width is approximately twice that of each gena (tr.) whereas in the Welsh form the corresponding ratio numbers between 1.5 and 1.75. Punctation of the exoskeleton is also slightly less coarse than in A. inarmatus, and the occipital ring is less elevated and without a median node. The thorax and pygidium of A. inarmatus are unknown.

A. inarmatus minutus Sdzuy (2000, pl.3 fig. 5; Heuse et al., [23] p. 113. Fig. 4, illustration 16), possibly based on an immature specimen, is clearly related to both A. inarmatus and A. sp. nov.; the subspecies particularly resembles A. inarmatus in the marked forward expansion of its glabella and small genae, but from the illustration there is no clear evidence of lateral glabellar furrows as seen in Hutchinson's species. A. sp. nov. has larger genae and the glabella less expanded frontally than in minutus.

According to Westergärd (1950, p.9) the pygidium of A. acutangulus is apparently almost as large as its cephalon, whereas A. sp. nov. is distinctly heteropygous.

The pygidial axis in Acontheus cf. acutangulus (Jago et. al., 2011, fig. 7, N-S) is narrower (tr.) than in the Swedish species and terminates slightly short of the posterior border furrow, whereas in both A. acutangulus Angelin, 1851 and A. sp. nov., the axis actually meets the border furrow and separates the pleural fields, as also observed in Clavigellus annulus Geyer (1994, figs. 6-8).

In their ‘Revised diagnosis’ of Acontheus, Jago et al. (2011, p.29) stated that pygidial pleural furrows are “wide, deep, extend to border with marked posterior deflection where they cross border furrow. Interpleural furrows effaced”. In Acontheus sp. nov., however, it is clearly the interpleural furrows that give the pygidial border its lobed character and, without rearward deflection as observed in the type species, A. cf, acutangulus, Jago et al. (op. cit.) and Clavigellus annulatus, Geyer (op.cit.).

References

- Sepkoski, Jack (2002). "A compendium of fossil marine animal genera (Trilobita entry)". Bulletins of American Paleontology. 364: 560. Archived from the original on 2006-09-05. Retrieved 2008-01-12.

- KOBAYASHI, T. (1935). The Cambro-Ordovician Formations and Faunas of South Chosen. Palaeontology, Pt.3, Cambrian Faunas of South Chosen with a Special Study on the Cambrian Genera and Families. Jour. Fac, Sci, Imp, Univ, Tokyo, Sec.II, V.4, pt.2, pp.49-344.

- ANGELIN, N. P. (1854). Paleontologica Scandinavica. Pars 2. Crustacea formationis transitionis. Academiae Regiae Scientiorum Suecanae (Holmiae): I-IX + 21-92.

- WESTERGÅRD, A. H. (1950). Non-Agnostidean trilobites of the Middle Cambrian of Sweden. II. Sver. geol. Unders. Afh.,Ser. C, 511, 1-56, pl.1-8.'

- ANGELIN, N. P. (1851). Palaeontologia suecica. Pars 1. Iconographia crustaceorum formationis transitionis. Fasc. 1, pp.1-24, pls.1-19.

- GEYER, G. 1994. Cambrian corynexochid trilobites from Morocco. Journal of Paleontology, 68, 1306-1320>

- POLETAEVA, O. K. 1956. Semejstvo Triniidae Poletayeva fam. nov., p. 178–179. In Kiparisova, L. D., Markovskij, B. P., and Radchenko, G. P. (eds.), Materialy po paleontologii. Novye semejstva i rody. Vsesoyuznyi Nauchno-issledovatel'skii Geologicheskii Institut (VSEGEI), Trudy, Novaya Seriya, 12.

- SUVOROVA, N. P. 1964. [Corynexochoid trilobites and their evolutionary history]. Trudy Paleontologichekogo Institita 103: 1-319, pls 1-31.

- REPINA, L. N., KHOMENTOVSKY, V. V., ZHURAVLEVA, I. T. and ROZANOV, A. YU. 1964. Biostratigraphiya nizhnego Kembriya Sayano-Altaiskoi skladchatoi oblasti [Biostratigraphy of the Lower Cambrian in the Sayan-Altai folded region]. Izdatelstvo `Nauka', Moskva, 364 pp., 48 pls. [In Russian].

- COTTON, T. J. 2001. Palaeontology, Vol. 44, Part 1, pp. 167-207, 4 pls.

- ILLING, V. C. 1916. The paradoxidian fauna of a part of the Stockingford Shales. Quarterly Journal of the Geological Society, London, 71, 386-450.

- LAKE, P. 1940. A monograph of the British Cambrian Trilobites, Part XII. Monograph of the Palaeontographical Society, pp. 273-306, pls. 40-43.

- ÖPIK, A. A., 1982. Dolichometopid trilobites of Queensland, Northern Territory, and New South Wales. Bureau of Mineral Resources, Geology and Geophysics, Bulletin 175, 1-85, pl. 1-32.

- BARRANDE, J. (1856). Bemerkungen über einige neue Fossilien aus der Umgebung von Rokitzan im Silurischen Beken von Mittel-Böhmen. Jahrbuch der Kaiserlichen-königlichen geologischen Reich-sandstalt 2, 355,1-6.

- JAGO, J. B., BENTLEY, C. J. & COOPER, R. A, 2011. A Cambrian Series 3 (Guzhangian) fauna with Centropleura from Northern Victoria Land, Antarctica. Memoirs of the Association of Australasian Palaeontologists 42, 15-35. ISSN 0810-8889

- HUTCHINSON, R. D., 1962. Cambrian stratigraphy and trilobite faunas of southeastern Newfoundland. Geological Survey of Canada, Bulletin 88, 1-156.

- SDZY, K., 2000. Das Kambrium des Frankenwaldes. 3. Die Lippertsgrüner Schichten und ihre Fauna. Senckenbergiana lethaia 79, 301-327

- GEYER, G., 2010. Cambrian and lowermost Ordovician of the Franconian Forest. 78-92 in Fatka, O. & Budil, P. (eds), The 15th Field Conference of the Cambrian Stage Subdivision Working Group, Abstracts and Excursion Guide. Czech Geological Survey, Prague, 108 pp.

- LAZARENKO, N. P., 1965. Some new Middle Cambrian trilobites from north central Siberia. Uchenye Zapiski Paleontologiya i Biostratigrafiya 7, 14-36.

- ÖPIK, A. A., 1961. The geology and palaeontology of the headwaters of the Burke River, Queensland. Bureau of Mineral Resources, Geology and Geophysics, Bulletin 53, 1-249.

- REES, A. J., THOMAS, A. T., LEWIS, M., HUGHES, H. E. & TURNER, P. 2014. The Cambrian of SW Wales: Towards a United Avalonian Stratigraphy. Geological Society, London, Memoirs, 42, 1–30.

- EGOROVA, L. I., SHABANOV, Y. Y., PEGEL, V. E., SAVITSKY, V. E., SUCHOV, S. S. and TCHERNYSHEVA, N. E. 1982. The Mayan stage of the type locality (Middle Cambrian of the Siberian platform). Trudy Mezhvedomstvennyi Stratigraficheskii Komitet SSSR, 8, 146 pp. [In Russian].

- HEUSE, T., BLUMENSTENGEL, H., ELICKI, O., GEYER, G., HANSCH, W., MALETZ, J., SARMIENTO, G. N., WEYER, D. (2010) Biostratigraphy – The faunal province of the southern margin of the Rheic Ocean. In Linneman, U. & Romer, R. L. (eds.) Pre-Mesozoic Geology of Saxo-Thuringia – From the Cadomian Active Margin to the Variscan Orogen. Schweizerbart, Stuttgart, pp. 99-170.