Academia Argentina de Letras

The Academia Argentina de Letras is the academy in charge of studying and prescribing the use of the Spanish language in Argentina. Since its establishment, on August 13, 1931,[1] it has maintained ties with the Royal Spanish Academy and the other Spanish-language academies that are members of the Association of Spanish Language Academies. Since 1999, it has officially been a correspondent academy of the Royal Spanish Academy.[2]

It currently includes two dozen full members,[2] chosen for having distinguished themselves in academic study related to language or literature. They make up the directing body of the academy, and they select honorary and correspondent academic members.

History

Antecedents

The earliest lexicographical projects in the Río de la Plata area included a limited but rigorous work titled Léxico rioplatense, compiled in 1845 by Francisco Javier Muñiz, and another lexicon put together in 1860 by Juan María Gutiérrez for the French naturalist and geographer Martin de Moussy.

On July 9, 1873, a group of Argentine intellectuals, mostly porteños (residents of the Buenos Aires area), founded the Argentine Academy of Sciences and Letters. Led by the poet Martín Coronado, this academy did not solely focus on the study of the Spanish language; it was dedicated to the various branches of knowledge, from law and science to visual art, literature, and history, as they pertained to Argentina's national culture. The academy did attempt to compile a Dictionary of the Argentine Language, for which the group's members compiled thousands of words and phrases.

However, with the dissolution of the academy in 1879 the project was left unfinished. This work, which included studies completed by experts concerning professional argots and research on localisms in Argentina's interior, was almost completely lost. Only a dozen of the vocabulary words were preserved, having been published in the academy's periodical, El Plata Literario. The same periodical announced in 1876 a Collection of American Voices, the work of Carlos Manuel de Trelles, which included contributions from some 300 people. But this uncompleted work of compiling an Argentine dictionary did at least demonstrate the need for an entity dedicated to studying the local language. When in the 1880s the Royal Spanish Academy began inviting various Argentine intellectuals—including Ángel Justiniano Carranza, Luis Domínguez, Vicente Fidel López, Bartolomé Mitre, Pastor Obligado, Carlos María Ocantos, Ernesto Quesada, Vicente Quesada, and Carlos Guido Spano—to assist in creating a correspondent language academy in Argentina, others—such as Juan Bautista Alberdi, Juan María Gutiérrez, and Juan Antonio Argerich—doubted the utility of joining the Spanish project, suspecting it was intended to restore peninsular culture to the country, to the detriment of Argentine culture. Argerich argued that such an academy would constitute "a branch that is a vassal of Spanish imperialism," and he counterproposed the creation of "an Argentine Academy of the Spanish Language" that would create its own dictionary. Obligado, on the other hand, argued publicly in favor of establishing an academy linked to the Royal Spanish Academy.

In 1903, Estanislao Zeballos, in his contribution to Ricardo Monner Sans' Notas al castellano en la Argentina, unsuccessfully proposed that the Argentine correspondent members of the Royal Spanish Academy at the time—Bartolomé Mitre, Vicente Fidel López, Vicente G. Quesada, Carlos Guido Spano, Rafael Obligado, Calixto Oyuela, Ernesto Quesada, and himself—form an Argentine section of the academy. It was not until seven years later, through the efforts of the marquess of Gerona, Eugenio Sellés, who came to Argentina as part of the entourage escorting the Infanta Isabella to the festivities commemorating the country's centenary, that those same men founded the first Academia Argentina de la Lengua. Of the 18 academics who were founding members, Vicente Quesada and Calixto Oyuela were chosen as president and secretary for life, respectively.

Obligado came up with a plan of action that included not only the work of editing and expanding the local lexicon contained in the dictionary of the Royal Spanish Academy but also working with the other Latin American academies to coordinate a register of local phrases, with the aim of creating a separate Latin American dictionary. With this he sought to avoid issues of nationalistic zeal and purism from the Spaniards, which had already caused friction with other correspondent academies. The Diccionario de americanismos would be available for the Royal Spanish Academy to use, but it would primarily constitute a separate undertaking.

The group was expanded at Zeballos' insistence, with the addition of several new members of the academy: Samuel Lafone Quevedo, Osvaldo Magnasco, José Matienzo, José María Ramos Mejía, and Enrique Rivarola. However, a lack of political support and mutual friction with the Spanish academy led to the rapid dissolution of the body, which was never able to publish its research.

Founding

On August 13, 1931, the de facto president José Félix Uriburu decreed the creation of the Academia Argentina de Letras. The name change (from "la Lengua," meaning "the Language," to "Letras," meaning "Letters" or "Literature") acknowledged an additional emphasis on the distribution and promotion of Argentine literature in addition to the academy's interest in the Spanish language in the country. With this dual mission, the academy sought to define and strengthen the "spiritual physiognomy of the country," using narrative, lyrical, and above all theatrical work to develop a cultural model. Oyuela was installed as president of the body, whose other members were Enrique Banchs, Joaquín Castellanos, Atilio Chiappori, Juan Carlos Dávalos, Leopoldo Díaz, Juan Pablo Echagüe, Alfredo Ferrerira, Gustavo Franceschi, Manuel Gálvez, Leopoldo Herrera, Carlos Ibarguren, Arturo Marasso, Gustavo Martínez Zuviría, Clemente Ricci, and Juan Bautista Terán. The academy was given the role of "associate" of the Royal Spanish Academy. It had all the support that its previous incarnation had lacked; a room in the old National Library on México Street was reserved for the group's weekly meeting while then-senator Matías Sánchez Sorondo worked to acquire the Palacio Errázuriz to house the academy, as well as the National Academy of Fine Arts, the National Museum of Decorative Arts, and the National Cultural Commission. The acquisition was approved in January of 1937, although the transfer of the building to the academy was not effective until 1944.

Development

There have been only a few institutional changes since the academy's creation by Uriburu: Since 1935, each of the academy's 24 seats bears the name of a classic Argentine writer. Since 1940, the emblem of the academy, designed by the artist Alfredo Guido, has been an ionic column alongside the motto "Recta sustenta." After the military coup of 1955, the self-proclaimed Revolución Libertadora regime led by Pedro Eugenio Aramburu initiated a policy of persecution of journalists, athletes, politicians, and intellectuals with ties to Peronism or other political movements, and among those who were targeted were members of the Academia Argentina de Letras.

In 1999, the academy was finally given the status of correspondent to the Royal Spanish Academy. In 2001 it celebrated its 70th anniversary with an exhibition at the National Library, which displayed documents and objects from its history.

Work

The aim of the Academia Argentina de Letras is not limited to registering the peculiarities of the Spanish language as it is spoken in the Río de la Plata Basin of Argentina and Uruguay, which is known as Rioplatense Spanish. It also works to regulate its use and to stimulate and contribute to literary study, which are both considered crucial elements of Argentina's national culture.

The academy also oversees national literary prizes. Since 1984 it has given out an award to university graduates who majored in literature and achieved the highest grade point average in all of the country's universities, as well as a prize for prominent authors of prose, poetry, and essays.[3]

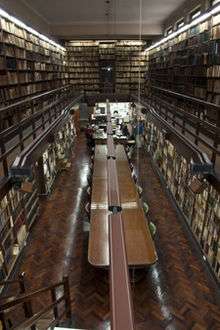

"Jorge Luis Borges" Library

The academy's library, now named for the Argentine writer Jorge Luis Borges, was inaugurated in 1932. It was based out of the National Library from 1932 to 1946, and in 1947 it moved to its current site at the Palacio Errázuriz in Buenos Aires. Thanks to a bequest from Juan José García Velloso, in 1936 the library gained 3,000 books of Latin American literature and theater. The collection of Alberto Cosito Muñoz, acquired in 1937, and issues of the Revue Hispanique and of publications of the Society of Spanish Bibliophiles supplemented the initial collection. Standouts of the library's holdings include Abraham Rosenvasser's Egyptology collection and Miguel Lermon's large collection of 19th century first editions. The collection specializes in works on linguistics and Argentine, Spanish, and Latin American literature, and it is one of the most important in Argentina.

The library of the Academia Argentina de Letras has inherited the important personal collections of: Juan José and Enrique García Velloso (3,341 volumes), Rafael Alberto Arrieta (4,000 vol.), Alfredo de la Guardia (3,000 vol.), Abraham Rosenvasser (2,400 vol.), Celina Sabor de Cortazar (1,000 vol.), Ofelia Kovacci (2,000 vol.), Marietta Ayerza and Alfredo González Garaño (4,000 vol.), José Luis Trenti Rocamora (23,000 vol.), Miguel Lermon (12,000 vol.), Juan Manuel Corcuera (2,400 vol.), and Manuel Gálvez (1,685 vol.).

Today, the library holds almost 130,000 volumes, as well as an important periodicals archive with examples of 3,000 publications that add up to around 16,000 volumes, forming a valuable research center. It also holds 2,000 antique books published between 1515 and 1801.

The library also holds four significant collections of correspondence: those of Manuel Gálvez, Roberto Giusti, Atilio Chiáppori, and Victoria Ocampo. The first three are available to read in full at the library. The library has also made available via the Miguel de Cervantes Virtual Library its collection of Gaucho literature, its collection of travel literature related to the region, and a set of historic documents gathered by Pedro de Angelis.

Department of Philological Research

The Departamento de Investigaciones Filológicas (Department of Philological Research) was initially founded in 1946, with the aim of providing research and technical advice. In 1955, by presidential degree, it was merged with the Institute of Tradition to form the National Institute of Philology and Folklore. The new institute's work was regulated in 1961, but it was not until 1966 that, under the direction of Carlos Ronchi March, the processes around maintaining its archives and producing lexicographical reports were formalized. The department currently advises the academy's plenary, prepares notes and additions for the Royal Spanish Academy, and maintains archives and documentation about localized speech in Argentina.

Publications

Since its founding, the academy has published a quarterly Bulletin on philological and lexicographic topics. The periodical was conservative and closely allied with the Spanish academy from the first issue, in which Juan Bautista Terán denied the existence of a "language of the Argentines" and emphasized the continuity between Rioplatense Spanish and the Spanish spoken on the Iberian Peninsula. The goal on selecting a fixed, normative corpus for the national language was evidenced by the "Bibliography of Castilian in Argentina," published starting in that issue, which sought to compile a selection of worthy works of national literary production. The academy also worked to protest and correct examples of nonstandard language in periodicals, advertisements, and administrative writing. Circulars were issued to newspapers and radio broadcasters, as well as to municipal and national government bodies. The Bulletin of the Academia Argentina de Letras is still published today.[4]

In 1941, the academy launched a collection of anthologies and literary criticism of "Argentine Classics," of which 26 volumes were published. Starting in 1946, they added to this a collection of "Academic Studies," which paired translations of foreign literature with critical studies and national biographies, and in 1976 they added a series of "Linguistic and Philological Studies."

Beyond those publications already mentioned, since 1947 the Bulletin has occasionally been accompanied by volumes honoring outstanding authors. Beginning in 1975 they began distributing these tributes more regularly, publishing 25 such volumes to date. Additionally, the academy has published various books, including a Dictionary of Americanisms by Augusto Malaret, the first book of the unfinished Etymological Dictionary of Common Spanish by Leopoldo Lugones, the minutes of the 4th Congress of the Association of Spanish Language Academies, a Lexicon of Cultured Speech of Buenos Aires, a book of Common Idiomatic Questions, a Record of Argentine Speech, 12 volumes of Agreements on the Language settled by the academy, and some literary works. Currently in the works is a large-scale Dictionary of Argentine Speech that registers the use of the Spanish language in the country.

References

- "Academia Argentina de Letras". www.aal.edu.ar. Retrieved 2020-08-04.

- "Academia Argentina de Letras". www.asale.org (in Spanish). Retrieved 2020-08-04.

- "Premio Literario de la Academia Argentina de Letras | Academia Argentina de Letras". www.aal.edu.ar. Retrieved 2020-08-04.

- "Boletín de la Academia Argentina de Letras". www.catalogoweb.com.ar. Retrieved 2020-08-05.