Aberchalder

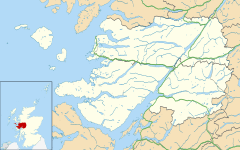

Aberchalder (Gaelic: Obar Chaladair) is a small settlement and estate at the northern end of Loch Oich in the Scottish Highlands and is in the Highland council area of Scotland. It lies on the A82 road and is situated in two parishes, Boleskine and Kilmonivaig.[1] Fort Augustus is within 5 mi (8.0 km).[2]

Aberchalder

| |

|---|---|

Loch Oich | |

Aberchalder Location within the Lochaber area | |

| OS grid reference | NH340032 |

| Council area | |

| Country | Scotland |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Postcode district | PH35 |

| Police | Scotland |

| Fire | Scottish |

| Ambulance | Scottish |

| UK Parliament | |

| Scottish Parliament | |

Etymology

The town is named for its location. The prefix Aber refers to "the mouth" or "confluence", while the suffix Chalder translates to "of the calder". Calder itself is a corruption of Coille Dur with Coille meaning "of the wood" and Dur used as an obsolete Gaelic term for "water".[3]

History

Aberchalder was owned at one time by Randolph, Earl of Moray, then passing to Dunbar, Earl of Moray, and later to the Clan Fraser of Lovat, and still later to Glengarry.[4] On 27 August 1745 the MacDonnell of Glencoe's and Glengarry's Regiment joined the Scottish Jacobite Army at Aberchalder.[5] In 1812, residents of Aberchalder produced a petition which led to the building of a road connecting the eastern part of the Loch Oich to Loch Hourn.[6]

A swing bridge is located in the area, the Caledonian Canal and locks (Cullochy Lock), built upon rocks. The locks were afforded to allow a depth of over 20 feet over its upper-gate sills. The canal flooded during the great floods of November 1834, rising some 27 feet and 3 inches above the upper-gate sills.[7] Immediately before entering the loch, the Aberchalder Burn, a rapid mountain torrent, empties itself into the canal. Despite extensive work on the canal with cement in the summer of 1839, in 1849, further floods washed away the old bridge at Aberchalder, which subsequently led to a dredging of the canal. A new bridge, named the Victoria Bridge, was built about five years later. The new bridge was designed by James Dredge, a brewer turned civil engineer from Bath.[8] In 1932, another bridge was built to accommodate traffic.

The area was once served by the Aberchalder railway station. It was opened by the Highland Railway (Invergarry and Fort Augustus Railway) and became part of the North British Railway, joining the London and North Eastern Railway during the Grouping of 1923. The line closed in 1935.[9]

Aberchalder gives its name to the 16,000 acre (65 km²) Aberchalder Estate which has been owned by the Ellice family since the 1860s.

Aberchalder Lodge

Aberchalder Lodge is a country house in the Inverness-shire region of Scotland's Highland Council area. The original part of the Lodge dating from the 17th Century was destroyed in a fire in the 1980s. The remaining part of the building dates from 1934. It lies at the centre of the 16,000 acre (65 km²) Aberchalder Estate close to Loch Oich.

Geography

There are several mountains and hills in the Aberchalder area. These include, Ben Van (Bewinn Bhan), Beinn Laragan, Carn Dearg, Carn na Larach, Goat's Crag (Craegan nan Gobhar), Eldrig, Leacann doire bannear (2091 feet), Letterfearn (Leitir Fearn), and Mullach a'Ghlinne (1734 ft). The three smaller rivers include Allt na Criche, Coachan a'Bhrudhaiste, and Fairies' Burn (Allt nan Sithean). Calder Burn, namesake of the town, is a river that runs through the district's wood for almost its entire length. Bealach Strep is a steep pass south of Laggan. Field of the Shirts (Blar na Leine) was the site of a 1543 feud between the Clan Ranald of Moydert and the Frasers. Maiden's Leap (Ceum na Nighean) is a rock, difficult to pass, that lies on the road between Aberchalder and Laggan. Coille Shlugan is a wood and Dalruary (Dal ruairdh) is a field. Shian (Dubh Sithean) is a knoll, specifically the black fairies' knoll, the fairies having been worshipped by the ancient inhabitants of this area. Feil Droman was a market ridge where an annual fair used to be held.[10]

Notable people

- Donald Macdonell (1778–1861), political figure in Upper Canada[11]

- Hugh McDonell, political figure in Upper Canada[11]

- John McDonell, political figure in Upper Canada[11]

- John Lamont (fl. 1814), priest[12]

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Aberchalder. |

- Google Maps (Map). Google.

- Groome, Francis Hindes (1882). Ordnance gazetteer of Scotland: a survey of Scottish topography, statistical, biographical and historical. 1. T. C. Jack. p. 5.

- Ellice, p. 57, 60

- Mackay, John; Mackay, Annie Maclean Sharp (1901). Sinclair, Archibald (ed.). The Celtic monthly: a magazine for Highlanders. 9. Celtic Press. p. 51.

- Reid, Stuart; Zaboly, Gary (2006). The Scottish Jacobite Army 1745–46. Osprey Publishing. p. 21. ISBN 1-84603-073-0.

- Bumsted, J.M. (1982). People's Clearance: Highland Emigration to British North America, 1770–1815. Univ. of Manitoba Press. p. 189. ISBN 0-88755-127-0.

- REPORTS FROM COMMITTEES CALEDONIAN AND CRINAN CANALS. 1839. p. 133.

- Dillon, Paddy (2007). The Great Glen Way. Brit Long-distance Series:A Cicerone guide. Cicerone Press Limited. pp. 57–59. ISBN 1-85284-503-1.

- Butt, R.V.J. (1995). The Directory of Railway Stations. Patrick Stephens Ltd. ISBN 1-85260-508-1.

- Ellice, Edward C . (1898). Place-names in Glengarry and Glenquoich, and their origin. Swan Sonnenschein. pp. 55–77.

- Johnson, James Keith (1989). Becoming prominent: regional leadership in Upper Canada, 1791–1841. McGill-Queen's Press - MQUP. pp. 208–9. ISBN 978-0-7735-0641-1.

- Fraser-Mackintosh, Charles (1890). Letters of two centuries: chiefly connected with Inverness and the Highlands, from 1616 to 1815. A. & W. Mackenzie. pp. 369–70.

Aberchalder.