Plot (narrative)

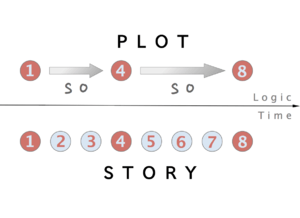

In a literary work, film, story or other narrative, the plot is the sequence of events where each affects the next one through the principle of cause-and-effect. The causal events of a plot can be thought of as a series of events linked by the connector "and so". Plots can vary from the simple—such as in a traditional ballad—to forming complex interwoven structures, with each part sometimes referred to as a subplot or imbroglio. In common usage (for example, a "movie plot"), however, it can mean a narrative summary or story synopsis, rather than a specific cause-and-effect sequence.

Plot is similar in meaning to the term storyline.[2][3] In the narrative sense, the term highlights important points which have consequences within the story, according to Ansen Dibell.[1] The term plot can also serve as a verb, referring to the writer's crafting of a plot (devising and ordering story events) or to a character's planning future actions in the story.

Definition

English novelist E. M. Forster described plot as the cause-and-effect relationship between events in a story. According to Forster, "The king died, and then the queen died, is a story, while The king died, and then the queen died of grief, is a plot."[4][5][6]

Teri Shaffer Yamada agrees that a plot does not include memorable scenes within a story which do not relate directly to other events but only "major events that move the action in a narrative."[7] For example, in the 1997 film Titanic, when Rose climbs on the railing at the front of the ship and spreads her hands as if she's flying, this scene is memorable but does not directly influence other events, so it may not be considered as part of the plot. Another example of a memorable scene which is not part of the plot occurs in the 1980 film The Empire Strikes Back, when Han Solo is frozen in carbonite.[1]

Cinderella

Consider the following:

- The prince searches for Cinderella with the glass shoe

- Cinderella's sisters tried the shoe on but it does not fit

- The shoe fits Cinderella's foot so the prince finds her

The first event is causally related to the third event, while the second event, though descriptive, does not directly impact the outcome. As a result, according to Dibell, the plot can be described numerically as 1→3 while the story can be described as 1→2→3. A story orders events from beginning to end in a time sequence.[1]

The Wizard of Oz

Steve Alcorn, a fiction-writing coach, says that the main plot elements of The Wizard of Oz are easy to find, and include:[8]

A tornado picks up a house and drops it on a witch, a little girl meets some interesting traveling companions, a wizard sends them on a mission, and they melt a witch with a bucket of water.[8]

Fabula and syuzhet

The literary theory of Russian Formalism in the early 20th century divided a narrative into two elements: the fabula (фа́була) and the syuzhet (сюже́т). A fabula is the events in the fictional world, whereas a syuzhet is a perspective of those events. Formalist followers eventually translated the fabula/syuzhet to the concept of story/plot. This definition is usually used in narratology, in parallel with Forster's definition. The fabula (story) is what happened in chronological order. In contrast, the syuzhet (plot) means a unique sequence of discourse that was sorted out by the (implied) author. That is, the syuzhet can consist of picking up the fabula events in non-chronological order; for example, fabula is <a1, a2, a3, a4, a5, ..., an>, syuzhet is <a5, a1, a3>.

The Russian formalist, Viktor Shklovsky, viewed the syuzhet as the fabula defamiliarized. Defamiliarization or “making strange,” a term Shklovsky coined and popularized, upends familiar ways of presenting a story, slows down the reader's perception, and makes the story appear unfamiliar.[9] Shklovsky cites Lawrence Sterne's Tristram Shandy as an example of a fabula that has been defamiliarized.[10] Sterne uses temporal displacements, digressions, and causal disruptions (for example, placing the effects before their causes) to slow down the reader's ability to reassemble the (familiar) story. As a result, the syuzhet “makes strange” the fabula.

Structure

Today screenwriters generally combine plot with plot structure into what is called a treatment, sometimes referred to as the three-act structure, in which a film is divided into three acts: the set-up, the confrontation and the resolution. Acts are connected by two plot points or turning points, with the first turning point connecting Act I to Act II, and the second connecting Act II to Act III. The conception of the three-act structure has been attributed to American screenwriter Syd Field who described plot structure in this tripartite way for film analysis.

Aristotle

The Greek philosopher Aristotle, writing in the fourth century BC in his classic book The Poetics, considered plot or mythos as the most important element of drama, even more important than character.[11] Aristotle wrote that a tragedy, a type of plot, could be divided into three parts: a beginning, a middle, and an end.[12] He also believed that the events of the plot must causally relate to one another as being either necessary or probable.[13] Of the utmost importance is the plot's ability to arouse emotion in the psyche of the audience, he thought. In tragedy, the appropriate emotions are fear and pity, emotions which he considers in his Rhetoric. (Aristotle's work on comedy has not survived.)

Aristotle goes on to consider whether the tragic character suffers (pathos), and whether the tragic character commits the error with knowledge of what he is doing. He illustrates this with the question of a tragic character who is about to kill someone in his family.

- The worst situation [artistically] is when the personage is with full knowledge on the point of doing the deed, and leaves it undone. It is odious and also (through the absence of suffering) untragic; hence it is that no one is made to act thus except in some few instances, for example, Haemon and Creon in Antigone. Next after this comes the actual perpetration of the deed meditated. A better situation than that, however, is for the deed to be done in ignorance, and the relationship discovered afterwards, since there is nothing odious in it, and the discovery will serve to astound us. But the best of all is the last; what we have in Cresphontes, for example, where Merope, on the point of slaying her son, recognizes him in time; in Iphigenia, where sister and brother are in a like position; and in Helle, where the son recognizes his mother, when on the point of giving her up to her enemy.(Poetics book 14)

Freytag

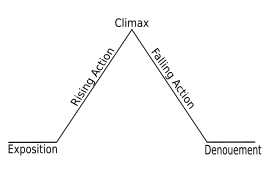

In 1863, Gustav Freytag, a German writer, advocated a model based upon Aristotle's theory of tragedy. This is now called "Freytag's pyramid," which divides a drama into five parts, and provides function to each part. These parts are: exposition (originally called introduction), rising action (rise), climax, falling action (return or fall), and denouement (catastrophe).[14]

Exposition

The first phase in Freytag's pyramid is the exposition, which introduces the characters, especially the main character, also known as the protagonist. It shows how the characters relate to one another, their goals and motivations, as well as their moral character. During the exposition, the protagonist learns their main goal and what is at stake.[15]

Rising action

Rising action is the second phase in Freytag's five-phase structure. It starts with a conflict, for example, the death of a character. The inciting incident is the point of the plot that begins the conflict. It is the event that catalyzes the protagonist to go into motion and to take action. Rising action involves the buildup of events until the climax.

In this phase, the protagonist understands his or her goal and begins to work toward it. Smaller problems thwart their initial success and their progress is directed primarily against these secondary obstacles. This phase demonstrates how the protagonist overcomes these obstacles.[16]

Climax

The climax is the turning point or highest point of the story. The protagonist makes the single big decision that defines not only the outcome of the story, but also who they are as a person. Freytag defines the climax as the third of the five dramatic phases which occupies the middle of the story.

At the beginning of this phase, the protagonist finally clears away the preliminary barriers and engages with the adversary. Usually, both the protagonist and the antagonist have a plan to win against the other as they enter this phase. For the first time, the audience sees the pair going against one another in direct or nearly direct conflict.

This struggle usually results in neither character completely winning or losing. In most cases, each character's plan is both partially successful and partially foiled by their adversary. The central struggle between the two characters is unique in that the protagonist makes a decision which shows their moral quality, and ultimately decides their fate. In a tragedy, the protagonist here makes a poor decision or a miscalculation that demonstrates their tragic flaw.[17]

Falling action

According to Freytag, the falling action phase consists of events that lead to the ending. Character's actions resolve the problem. In the beginning of this phase, the antagonist often has the upper hand. The protagonist has never been further from accomplishing their goal. The outcome depends on which side the protagonist has put themselves on.[18]

Denouement

In this phase the protagonist and antagonist have solved their problems and either the protagonist or antagonist wins the conflict. The conflict officially ends. Some stories show what happens to the characters after the conflict ends and/or they show what happens to the characters in the future.[19]

Northrop Frye

In The Great Code, Northrop Frye argues that the plot of the Hebrew and Christian Bible is a series of ups and downs or a series of U-shaped structures, the standard shape of comedies, and inverted U-shaped structures, the standard shape of tragedies.[20] The U-shaped and inverted U-shaped plots are a continuous series of disasters and restorations that begins in Genesis with the loss of the tree and water of life and ends in Revelation with the tree and water of life restored.[21]

U-shaped Structure (Comedy)

The plot begins at the top of the U with stability and equilibrium that is disrupted by an event or happening that causes a descent to disaster. The bottom of the U is the plot’s nadir. A recognition scene or anagnorisis occurs followed by a peripeteia or reversal that moves the plot upward to its denouement and a new state of equilibrium and stability. In the Christian Bible, the Parable of the Prodigal Son in Luke 15:11-24 is a classic U-shaped plot.[22]

Inverted U-shaped Structure (Tragedy)

The introduction of a conflict initiates the rising action, the beginning of the upward turn of the inverted U. The conflict is developed and complicated until the rising action reaches the climax of the protagonist’s fortunes. This is the top of the inverted U. A crisis or turning point marks the reversal of the protagonist’s fortunes and begins the descent to disaster. The denouement involves a reversal in the character’s fortune that ends in a new state of disequilibrium marked by disaster, adversity, or unhappiness.[23]

Plot devices

A plot device is a means of advancing the plot in a story. It is often used to motivate characters, create urgency, or resolve a difficulty. This can be contrasted with moving a story forward with dramatic technique; that is, by making things happen because characters take action for well-developed reasons. An example of a plot device would be when the cavalry shows up at the last moment and saves the day in a battle. In contrast, an adversarial character who has been struggling with himself and saves the day due to a change of heart would be considered dramatic technique.

Familiar types of plot devices include the deus ex machina, the MacGuffin, the red herring, and Chekhov's gun.

Plot outline

A plot outline is a prose telling of a story which can be turned into a screenplay. Sometimes it is called a "one page" because of its length. It is generally longer and more detailed than a standard synopsis, which is usually only one or two paragraphs, but shorter and less detailed than a treatment or a step outline. In comics, the roughs refer to a stage in the development where the story has been broken down very loosely in a style similar to storyboarding in film development. This stage is also referred to as storyboarding or layouts. In Japanese manga, this stage is called the nemu (pronounced like the English word "name"). The roughs are quick sketches arranged within a suggested page layout. The main goals of roughs are to:

- lay out the flow of panels across a page

- ensure the story successfully builds suspense

- work out points of view, camera angles, and character positions within panels

- serve as a basis for the next stage of development, the "pencil" stage, where detailed drawings are produced in a more polished layout which will, in turn, serve as the basis for the inked drawings.

In fiction writing, a plot outline is a laundry list of scenes with each line being a separate plot point, and the outline helps give a story a "solid backbone and structure".

A-Plot

An A-Plot is a cinema and television term referring to the plotline that drives the story. This does not necessarily mean it is the most important, but rather the one that forces most of the action.

Plot summary

A plot summary is a brief description of a piece of literature that explains what happens. In a plot summary, the author and title of the book should be referred to and it is usually no more than a paragraph long while summarizing the main points of the story.[24][25]

See also

- Gustav Freytag

- Monomyth

- Mythos (Aristotle)

- Narrative

- Narrative structure

- Narrative thread

- Plot drift

- Plot hole

- Premise (narrative)

- Robert McKee

- Scene and sequel

- Subplot

- Syd Field: Three-act structure in screenplays and films

- Theme (narrative)

- The Seven Basic Plots, a book by Christopher Booker

- The Thirty-Six Dramatic Situations, which is Georges Polti's categorization of every dramatic situation that might occur in a story or performance.

Notes

- Ansen Dibell, Ph.D. (1999-07-15). Plot. Elements of Fiction Writing. Writer's Digest Books. pp. 5 f. ISBN 978-0-89879-946-0.

Plot is built of significant events in a given story – significant because they have important consequences. Taking a shower isn't necessarily plot... Let's call them incidents ... Plot is the things characters do, feel, think or say, that make a difference to what comes afterward.

- Random House Dictionary. "plot."

- Oxford Dictionaries. "storyline."

- Prince, Gerald (2003-12-01). A Dictionary of Narratology (Revised ed.). University of Nebraska Press. p. 73. ISBN 978-0-8032-8776-1.

- Wales, Katie (2011-05-19). A Dictionary of Stylistics. Longman Linguistics (3 ed.). Routledge. p. 320. ISBN 978-1-4082-3115-9.

- Forster, E.M. Aspects of the Novel. Mariner Books. (1956) ISBN 978-0156091800

- Teri Shaffer Yamada, Ph.D. "ELEMENTS OF FICTION". California State University, Long Beach. Archived from the original on 2014-12-20. Retrieved 2014-12-20.

- Steve Alcorn. "Know the Difference Between Plot and Story". Tejix. Archived from the original on 2014-08-23. Retrieved 2014-08-24.

- Victor Shklovsky, “Art as Technique,” in Russian Formalist Criticism: Four Essays, 2nd ed., trans. Lee T. Lemon and Marion J. Reis (Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press, 2012), 3-24.

- Shklovsky, "Sterne's Tristram Shandy: Stylistic Commentary" in Russian Formalist Criticism, 25-57.

- Mack et al. (1985, pp. 843–844)

- Mack et al. (1985, p. 844)

- Mack et al. (1985, pp. 846–847)

- Freytag (1900, p. 115)

- Freytag (1900, pp. 115–121)

- Freytag (1900, pp. 125–128)

- Freytag (1900, pp. 128–130)

- Freytag (1900, pp. 133–135)

- Freytag (1900, pp. 137–140)

- Northrop Frye, The Great Code: The Bible and Literature (New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1982), 169-71. “This U-shaped pattern, approximates as it is, recurs in literature as the standard shape of comedy, where a series of misfortunes and misunderstandings brings the action to a threateningly low point, after which some fortunate twist in the plot sends the conclusion up to a happy ending,” 169.

- Frye, The Great Code, 169-71.

- James L. Resseguie, Narrative Criticism of the New Testament: An Introduction (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Academic, 2005), 205-206.

- Frye, The Great Code, 176.

- Stephen V. Duncan (2006). A Guide to Screenwriting Success: Writing for Film and Television. Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 33–. ISBN 978-0-7425-5301-9.

- Steven Espinoza; Kathleen Fernandez-Vander Kaay; Chris Vandar Kaay (20 August 2019). We All Know How This Ends: The Big Book of Movie Plots. Laurence King Publishing. ISBN 978-1-78627-527-1.

References

- Freytag, Gustav (1900) [Copyright 1894], Freytag's Technique of the Drama, An Exposition of Dramatic Composition and Art by Dr. Gustav Freytag: An Authorized Translation From the Sixth German Edition by Elias J. MacEwan, M.A. (3rd ed.), Chicago: Scott, Foresman and Company, LCCN 13-283

- Mack, Maynard; Knox, Bernard M. W.; McGaillard, John C.; et al., eds. (1985), The Norton Anthology of World Masterpieces, 1 (5th ed.), New York: W. W. Norton & Company, ISBN 0-393-95432-3

Further reading

- Obstfeld, Raymond (2002). Fiction First Aid: Instant Remedies for Novels, Stories and Scripts. Cincinnati, OH: Writer's Digest Books. ISBN 1-58297-117-X.

- Foster-Harris (1960). The Basic Formulas of Fiction. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press. ASIN B0007ITQBY.

- Polking, K (1990). Writing A to Z. Cincinnati, OH: Writer's Digest Books. ISBN 0-89879-435-8.

External links

| Look up plot in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

- The "Basic" Plots In Literature, Information on the most common divisions of the basic plots, from the Internet Public Library organization.

- Plot on TV Tropes, a wiki catalog of the tricks of the trade for writing fiction

- Plot Definition, meaning and examples

- The Minimal Plot, on cyclic structures of the basic plots by Yevgeny Slavutin and Vladimir Pimonov.