Aistopoda

Aïstopoda (Greek for "[having] not-visible feet") is an order of highly specialised snake-like amphibians known from the Carboniferous and Early Permian of Europe and North America, ranging from tiny forms only 5 centimetres (2 in), to nearly 1 metre (3.3 ft) in length. The first appear in the fossil record in the Mississippian period and continue through to the Early Permian.

| Aistopoda Temporal range: Early Carboniferous - Early Permian | |

|---|---|

| |

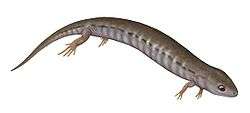

| Restoration of Oestocephalus amphiuminus | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Subclass: | †Lepospondyli |

| Node: | †Holospondyli |

| Order: | †Aistopoda Miall, 1875 |

| Subgroups | |

The skull is small but very specialised, with large orbits, and large fenestrae. The primitive form Ophiderpeton has a pattern of dermal bones in the skull similar in respects to the temnospondyls. But in the advanced genus Phlegethontia the skull is very light and open, reduced to a series of struts supporting the braincase against the lower jaw, just as in snakes, and it is possible that the Aïstopods filled the same ecological niches in the Paleozoic that snakes do today.

They had an extremely elongated body, with up to 230 vertebrae. The vertebrae were holospondylous, having only a single ossification per segment. They lacked intercentra, even in the tail, and had are no free haemal arches. The neural arch was low and fused to the centrum. All of these features are very similar to those of the Nectridea, both representing the typical lepospondylous condition.

A recent paper described the internal organization of the aïstopod head,[1] finding that aïstopods retained many fish-like features of the skull and brain, including a persistent extension of the notochord into the head and an open canal between the pituitary gland and the mouth. Because these features are lost early in tetrapod evolution, this may be evidence that aïstopods diverged from other tetrapods soon after the origin of digits.

The ribs were slender, either single or double-headed, with the head shaped like a letter "K". There is no trace of limbs or even limb girdles in any known fossil, and the tail was short and primitive.

Relationships

Evolutionary relationships with other early tetrapods remain controversial, as even the earliest aistopod, the Viséan species Lethiscus stocki, was already highly specialised. Aïstopods have been variously grouped with other lepospondyls, or placed at or prior to the batrachomorph-reptiliomorph divide. However, a cladistic analysis by Pardo et al. (2017) recovered Aistopoda at the base of Tetrapoda.[1] The group was quite diverse during the Late Carboniferous, with a few forms continuing through to the Permian.

Below is a cladogram from Anderson et al. (2003) showing the phylogenetic relationships of aistopods:[2]

|

References

- Jason D. Pardo, Matt Szostakiwskyj, Per E. Ahlberg & Jason S. Anderson (2017) Hidden morphological diversity among early tetrapods. Nature (advance online publication) doi:10.1038/nature22966>

- Anderson, J.S.; Carroll, R.L.; Rowe, T.B. (2003). "New information on Lethiscus stocki (Tetrapoda: Lepospondyli: Aistopoda) from high-resolution computed tomography and a phylogenetic analysis of Aistopoda" (PDF). Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences. 40 (8): 1071–1083. doi:10.1139/e03-023.

- Benton, M. J. (2000), Vertebrate Paleontology, 2nd ed. Blackwell Science Ltd

- Carroll, RL (1988), Vertebrate Paleontology and Evolution, WH Freeman & Co. pp. 176–7

- Reisz, Robert Biology 356 - Major Features of Vertebrate Evolution (online)

- von Zittel, K.A (1932), Textbook of Paleontology, CR Eastman (transl. and ed), 2nd edition, vol.2, p. 221-2, Macmillan & Co.