500 kHz

The radio frequency of 500 kilohertz (500 kHz) has been an international calling and distress frequency for Morse code maritime communication since early in the 20th century. For most of its history, the international distress frequency was referred to by its equivalent wavelength, 600 meters, or, using the earlier frequency unit name, 500 kilocycles (per second) or 500 kc.

The United States Coast Guard and comparable agencies of other nations once maintained 24-hour watches on this frequency, staffed by highly skilled radio operators. Many SOS calls and medical emergencies at sea were handled via this frequency until December 1999. However, because of the near disappearance of the commercial use of Morse code, the frequency is now rarely used. Emergency traffic on 500 kHz has been almost completely replaced by the Global Maritime Distress Safety System (GMDSS). Beginning in the late 1990s, most nations ended monitoring of transmissions on 500 kHz. The nearby frequencies of 518 kHz and 490 kHz are used for the Navtex component of GMDSS. Proposals to allocate frequencies at or near 500 kHz to amateur radio use resulted in the creation of the 630-meter band.

Initial adoption

International standards for the use of 500 kHz first appeared in the first International Radiotelegraph Convention in Berlin, which was signed November 3, 1906, and became effective July 1, 1908. The second Service Regulation affixed to this Convention designated 500 kHz as one of the standard frequencies to be employed by shore stations, specifying that "Two wave lengths, one of 300 meters [1 Mc/s] and the other of 600 meters, are authorized for general public service. Every coastal station opened to such service shall use one or the other of these two wave lengths." (These regulations also specified that ship stations normally used 1 MHz).[1][2]

Expanded policies

International standards for the use of 500 kHz were expanded by the second International Radiotelegraph Convention, which was held after the sinking of the RMS Titanic. This Convention, meeting in London, produced an agreement which was signed on July 5, 1912, and became effective July 1, 1913.

The Service Regulations, affixed to the 1912 Convention, established 500 kHz as the primary frequency for seagoing communication, and the standard ship frequency was changed from 1,000 kHz to 500 kHz, to match the coastal station standard. Communication was generally conducted in Morse code, initially using spark-gap transmitters. Most two-way radio contacts were to be initiated on this frequency, although once established, the participating stations could shift to another frequency to avoid the congestion on 500 kHz. To facilitate communication between operators speaking different languages, standardized abbreviations were used, including a set of "Q codes" specified by the 1912 Service Regulations.

Article XXI of the Service Regulations required that whenever an SOS distress call was heard, all transmissions unrelated to the emergency had to immediately cease until the emergency was declared over. There was a potential problem if a ship transmitted a distress call: the use of 500 kHz as a common frequency often led to heavy congestion, especially around major ports and shipping lanes, and it was possible the distress message would be drowned out by the bedlam of ongoing commercial traffic. To help address this problem, the Service Regulation's Article XXXII specified that "Coastal stations engaged in the transmission of long radiograms shall suspend the transmission at the end of each period of 15 minutes, and remain silent for a period of three minutes before resuming the transmission. Coastal and shipboard stations working under the conditions specified in Article XXXV, par. 2, shall suspend work at the end of each period of 15 minutes and listen in with a wave length of 600 meters during a period of three minutes before resuming the transmission." During distress working all non-distress traffic was banned from 500 kHz and adjacent coast stations then monitored 512 kHz as an additional calling frequency for ordinary traffic.

Later policies

The silent and monitoring periods were soon expanded and standardized. For example, Regulation 44, from the July 27, 1914, edition of Radio Communication Laws of the United States, stated: "The international standard wave length is 600 meters, and the operators of all coast stations are required, during the hours the station is in operation, to 'listen in' at intervals of not more than 15 minutes and for a period not less than 2 minutes, with the receiving apparatus tuned to receive this wave length, for the purpose of determining if any distress signals or messages are being sent and to determine if the transmitting operations of the 'listening station' are causing interference with other radio communication."

International refinements for the use of 500 kHz were specified in later agreements, including the 1932 Madrid Radio Conference. In later years, except for distress traffic, stations shifted to nearby "working frequencies" to exchange messages once contact was established. 425, 454, 468, 480, and 512 kHz were used by ships while the coast stations had their own individual working frequencies. Twice each hour, all stations operating on 500 kHz were required to maintain a strictly enforced three-minute silent period, starting at 15 and 45 minutes past the hour.

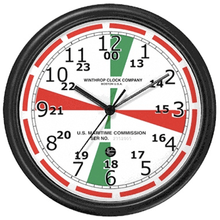

As a visual memory aid, a typical clock in a ship's radio room would have the silence periods marked by shading the sectors between h+15 to h+18 and h+45 to h+48 in RED. Similar sectors between h+00 to H+03 and h+30 to h+33 are marked in GREEN which is the corresponding silence period for the 2182 kHz voice communications distress signals. In addition, during this silent period all coastal and ship stations were required to monitor the frequency, listening for any distress signals.[3] All large ships at sea had to monitor 500 kHz at all times, either with a licensed radio operator or with equipment (called an auto-alarm) that automatically detected an SOS alarm signal.

Shore stations throughout the world operated on this frequency to exchange messages with ships and to issue warning about weather and other navigational warnings. At night, transmission ranges of 3,000–4,000 miles (4,500–6,500 kilometers) were typical. Daytime ranges were much shorter, on the order of 300–1,500 miles (500–2,500 kilometers). Terman's Radio Engineering Handbook (1948) shows the maximum distance for 1 kW over salt water to be 1,500 miles, and this distance was routinely covered by ships at sea, where signals from ships and nearby coastal stations would cause congestion, covering up distant and weaker signals. During the silence, a distress signal could more easily be heard at great distances.

Amateur radio

With maritime traffic largely displaced from the 500 kHz band, some countries have taken steps to allocate frequencies at or near 500 kHz to amateur radio use. In Belgium, amateurs were allocated a 501 to 504 kHz segment on a secondary basis on January 15, 2008. Only continuous wave (CW) may be used with a maximum effective radiated power (ERP) of 5 watts.[4] In Norway, the band segment 493–510 kHz was allocated to radio amateurs on November 6, 2009. Only radiotelegraphy is permitted.[5] In New Zealand, the band segment of 505 to 515 kHz was allocated temporarily, pending an international frequency allocation.[6] In the Netherlands Amateur radio operators have allocated the band segment from 501 to 505 kHz with a maximum of 100 watts PEP on January 1, 2012.[7]

See also

- 2182 kHz – the international distress frequency for voice maritime communication

- 630-meter band

- Navtex – a maritime weather and safety text broadcast on 518 kHz and 490 kHz

- Aircraft emergency frequency

- Call for help – for emergency frequencies in current use

- Distress signal

- GMDSS

- Mayday

- Medium frequency radio propagation

- Radio Act of 1912

- Radio propagation

- SOS

References

- Ken Beauchamp; Institution of Electrical Engineers (January 2001). History of Telegraphy. IET. pp. 256–. ISBN 978-0-85296-792-8.

- Anton A. Huurdeman (31 July 2003). The Worldwide History of Telecommunications. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 358–. ISBN 978-0-471-20505-0.

- Ships and the Sea. Kalmbach Publishing Co. 1954.

- Colin Thomas, G3PSM; Hans Timmerman, PB2T (2010-11-19). "500 kHz". IARU Region 1. Retrieved 2011-02-25.

- "Forskrift om radioamatørlisens (Amateur Radio Regulations)". www.lovdata.no (in Norwegian). Lovdata. Retrieved 2009-11-08.

- Roy Symon, ZL2KH (2010-02-24). "2010 NZ Amateurs Granted Access to 600 metre Band". NZART. Retrieved 2011-02-25.

- "Regeling van de Minister van Economische Zaken, Landbouw en Innovatie van 20 december 2011, nr. AT-EL&I/6621235, tot wijziging van de Regeling gebruik van frequentieruimte zonder vergunning 2008 in verband met de implementatie van twee besluiten van de Commissie van de Europese Gemeenschappen en het vergunningvrij maken van het gebruik van grond- en muur penetrerende radar" (in Dutch). overheid.nl. 2012-12-30. Retrieved 2012-01-03.

External links

- Berlin International Radiotelegraphic Convention of 1906

- Radio Laws and Regulations of the United States: Edition July 27, 1914. (Includes the 1912 London Radiotelegraphic Convention)

- Excellent first hand account of distress frequency communications

- International Telecommunication Union

- Marine and Coastguard Agency

- Merchant Shipping Regulations