4Q246

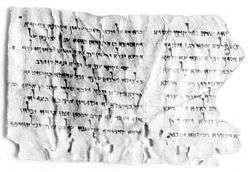

4Q246, also known as the Son of God Text or the Aramaic Apocalypse, is one of the Dead Sea Scrolls found at Qumran which is notable for an early messianic mention of a son of God.[1][2] The text is an Aramaic language fragment first acquired in 1958 from cave 4 at Qumran, and the major debate on this fragment has been on the identity of this "son of God" figure.[3]

Language

The Dead Sea Scrolls were written in Hebrew, Greek and Aramaic.[4] According to the time period of when the Son of God text was written, circa 100 BCE, it is highly probable that this Aramaic fragment was written using Jewish Palestinian Aramaic instead of official Aramaic.[5][4] Jewish Palestinian Aramaic was used between the time of 200 BCE and 200 CE, when sub-dialects were used to write the scrolls found in Qumran.[4]

This text is written in fine Herodian script, which is easily deciphered. The importance of this text to the tenets and theology of the Qumran community cannot be overestimated. Its language reveals it to be apocalyptic; it speaks of distress that will come upon the land and of the disastrous reign of enemies.[6]

Text

The Son of God page has a short text.[7] Column 1 (right hand) is damaged and requires some interpretative restoration. This is one of the smallest fragments found at cave 4, and people may wonder how big it is, and what it looks like. The text includes phrases such as "son of God" and "the Most High", so the two references of Daniel 7:13-14 and Luke 1:32-33, 35 are considered to be related to the fragmental phrases.[2] It is impossible to estimate exactly how long the complete scroll may have been, but the column length is only about half that of a normal size scroll. Paleographically, the text was said by Józef Milik (according to Fitzmyer) to date from the latter third of the first century BCE, a judgment with which Puech agrees. The letter forms are those of "early formal Herodian" script, although Milik's and Puech's dates may be too narrow.[2]

Below is the full text, formatted to reflect the actual text on the scroll. It is read from left to right, and the bracketed sections are the unknown parts where the scroll has been damaged:[2]

| Column II | Column I |

|---|---|

| 1. He will be called the son of God, they will call him the son of the Most High. But like the meteors

2. that you saw in your vision, so will be their kingdom. They will reign only a few years over 3. the land, while people tramples people and nation tramples nation. 4. Until the people of God arise; then all will have rest from warfare. 5. Their kingdom will be an eternal kingdom, and all their paths will be righteous. They will judge 6. the land justly, and all nations will make peace. Warfare will cease from the land, 7. and all the nations shall do obeisance to them. The great God will be their help, 8. He Himself will fight for them, putting peoples into their power, 9. overthrowing them all before them. God's rule will be an eternal rule and all the depths of 10. [the earth are His].[8] |

1. [. . . ] [a spirit from God] rested upon him, he fell before the throne.

2. [. . . O ki]ng, wrath is coming to the world, and your years 3. [shall be shortened . . . such] is your vision, and all of it is about to come unto the world. 4. [. . . Amid] great [signs], tribulation is coming upon the land. 5. [. . . After much killing] and slaughter, a prince of nations 6. [will arise . . .] the king of Assyria and Egypt 7. [. . .] he will be ruler over the land 8. [ . . .] will be subject to him and all will obey 9. [him.] [Also his son] will be called The Great, and be designated his name. |

Interpretation

One of the major debates among scholars on the son of God text is the identity of the figure called the "son of God." The text says he comes during "tribulation," his father "will be ruler over the land" and this figure "will be called The Great," and these two will reign for "a few years" while nations "trample" each other. While some say that this is an "eschatological prophet" or "messianic figure,"[9] others argue that this is "a negative figure," possibly a "Syrian king,"[10] such as Antiochus IV Epiphanes who is described in Daniel 7, an Antichrist figure.[8]

When part of 4Q246 was first published in 1974, the phrase "he will be called the son of God, and the son of the Most High" (col. 2:1) recalled to many scholars the language of the gospels when describing Jesus: "He will be great, and will be called the Son of the Most High" (Luke 1:32a) and he "will be called the Son of God" (v.35b).[11] This added proof in some scholars' eyes that the Jewish belief was that the coming Messiah would be a king who brought peace, and would be "called by Second Temple Jews the 'Son of God'".[8] But others viewed this figure "as a villain, one who usurps the place of God but is subsequently overthrown by the "people of God", who have God on their side."[8] When the full text was published, more researchers concluded that the latter interpretation was correct.[8]

There are several arguments for a messianic figure. First is the previously discussed parallel in Luke 1.[8][10] There is also a messianic parallel in 2 Samuel 7:12-14, where God tells David that from his offspring God will establish his eternal kingdom, and God "will be his father, and he will be [God's] son" (italics added).[12] Then, unlike the passage in Daniel 7, where the beast in the vision (Antiochus IV) is judged by God (vv. 11,26), the titles given to the figure in this manuscript are "never disputed, and no judgement is passed on this figure after the people of God arises."[10] These scholars also argue that Col. 2:4 is ambiguous, and could mean that the figure "will raise up the people of God", which makes him a savior figure, who could be present in times of tribulation.[10]

Given the context of the Hellenistic period and oppressive rule, many conclude the text is referring to Antiochus IV Epiphanes a Syrian tyrant from 170-164 BCE.[8] The title "Epiphanes" (Greek for "appearance") "encapsulates the notion of a human king as God manifest",[8] a boastful name that parallels this text's names, and the boastfulness of the little horn in Daniel 7.

The son of God text fragment has a complete second column and a fragmented first column suggesting that it was originally connected to another column.[13] Since the fragment is so small it is dangerous to come to a solid conclusion about this figure; a complete version of the text would likely solve this debate.[14]

References

- Fitzmyer, J A. 4Q246 The "Son of God" Document from Qumran. Biblica 1993 p153-174

- Edward Cook 4Q246 Bulletin for Biblical Research 5 (1995) 43-66 Archived 2008-11-20 at Archive.today

- Mattila, S.L (1994). "Two Contrasting Eschatologies at Qumran (4Q246 vs 1QM)". New Testament Abstracts. Biblica 75, no. 4: 518–538.

- "Languages and Scripts". The Leon Livy Dead Sea Scrolls Digital Library. 2012.

- Tigchelaar, Eibert (December 8, 2016). "Biblical Archaeology: Exploring The Dead Sea Scrolls (4Q246 Apocryphon of Daniel)". Dust Off The Bible.

- Fitzmyer, Jeseph (2000). The Dead Sea Scrolls and Christian Origins. Michigan: Grand Rapids. p. 54. ISBN 0-8028-4650-5.

- Graphic, transcription, translation at Wordpress.com

- A New Translation of The Dead Sea Scrolls. Translated by Wise, Michael; Abegg Jr., Martin; Cook, Edward. HarperOne. 1996. pp. 346–347.

- Evans, Craig A. (1997). Flint, Peter W. (ed.). Eschatology, Messianism, and the Dead Sea Scrolls. Grand Rapids, Michigan: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company. pp. 92–94, 121.

- Collins, John J. (1997). Apocalypticism in the Dead Sea Scrolls. London: Routledge. pp. 82–85.

- Hengel, Martin The Son of God: The Origin of Christology and the History of Jewish-Hellenistic Religion English translation 1976, p45

- Collins, John J. "The Background of the "Son of God" Text" (PDF). University of Chicago. p. 60.

- Brooke, George, J. (2005). Qumran: The Cradle of the Christ. Minneapolis: Fortress Press.

- Flint, Peter W.; Vanderkam, James C., eds. (1999). The Dead Sea Scrolls after Fifty Years: Volume II. Netherlands. pp. 413–415.