2005 Pacific hurricane season

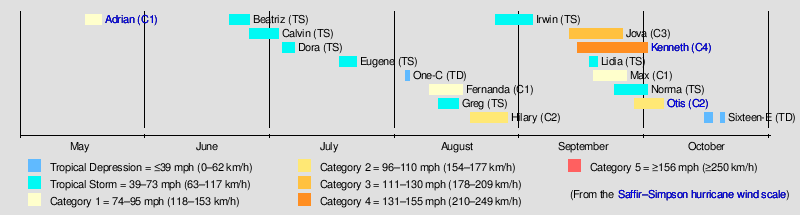

The 2005 Pacific hurricane season continued the trend of generally below-average activity that began a decade prior. The season officially began on May 15 in the eastern Pacific, and on June 1 in the central Pacific; it lasted until November 30 in both basins. These dates conventionally delimit the period during each year when most tropical cyclones form in the northeastern Pacific Ocean.[1] Activity began with the formation of Hurricane Adrian, the fourth-earliest-forming tropical storm on record in the basin at the time. Adrian led to flash flooding and several landslides across Central America, resulting in five deaths and $12 million (2005 USD) in damage. Tropical storms Calvin and Dora caused minor damage along the coastline, while Tropical Storm Eugene led to one death in Acapulco. In early October, Otis produced tropical storm-force winds and minor flooding across the Baja California peninsula. The remnants of Tropical Depression One-C in the central Pacific, meanwhile, caused minor impacts in Hawaii. The strongest storm of the season was Hurricane Kenneth, which attained peak winds of 130 mph (215 km/h) over the open Pacific. Cooler than average ocean temperatures throughout the year aided in below-average activity through the course of the season, which ended with 15 named storms, 7 hurricanes, 2 major hurricanes, and an Accumulated cyclone energy index of 75 units.

| 2005 Pacific hurricane season | |

|---|---|

Season summary map | |

| Seasonal boundaries | |

| First system formed | May 17, 2005 |

| Last system dissipated | October 20, 2005 |

| Strongest storm | |

| Name | Kenneth |

| • Maximum winds | 130 mph (215 km/h) (1-minute sustained) |

| • Lowest pressure | 947 mbar (hPa; 27.97 inHg) |

| Seasonal statistics | |

| Total depressions | 17 |

| Total storms | 15 |

| Hurricanes | 7 |

| Major hurricanes (Cat. 3+) | 2 |

| Total fatalities | 6 total |

| Total damage | $12 million (2005 USD) |

| Related articles | |

Pre-season forecasts

| Source | Date | Named storms |

Hurricanes | Major hurricanes |

Refs |

| Eastern | Average | 15–16 | 9 | 4–5 | [2] |

| SMN | February 2005 | 17 | 10 | 7 | [3] |

| NOAA | May 16, 2005 | 11–15 | 6–8 | 2–4 | [2] |

| Eastern | Actual activity | 15 | 7 | 2 | [4] |

| Central | Average | 4–5 | 1 | – | [5] |

| NOAA | May 16, 2005 | 2–3 | – | – | [5] |

| Central | Actual activity | 2 | 2 | 1 |

The first forecast for the 2005 season was produced by the Servicio Meteorológico Nacional (SMN) in the second month of the year. In their report, the organization cited a list of analog years – 1952, 1957, 1985, 1991, and 1993 – with similar oceanic and atmospheric patterns. An overall total of 17 tropical storms, 10 hurricanes, and 7 major hurricanes was forecast, above the average.[3] The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), meanwhile, released their seasonal outlook on May 16, predicting 11 to 15 named storms, 6 to 8 hurricanes, and 2 to 4 major hurricanes. The organization noted that when the Atlantic basin was busier than average, as expected in 2005, the eastern Pacific generally saw lesser activity.[2] That same day, NOAA issued a forecast for activity across the central Pacific, expecting 2 to 3 tropical cyclones to occur across the basin. A normal season averaged 4 to 5 tropical cyclones, including 1 hurricane. A near-normal El Niño–Southern Oscillation existed across the equatorial Pacific throughout 2005, which indicated conditions generally less conducive for activity there.[5]

Seasonal summary

The season's first tropical cyclone, Adrian, developed on May 17 and reached its peak as a Category 1 hurricane. Named storms are infrequent in May, with one tropical storm every two years and a hurricane once every four years.[6] At the time, Adrian was the fourth earliest tropical cyclone to form in the eastern Pacific since reliable record-keeping began in 1971. Activity throughout the remainder of the season was far less notable, with 16 tropical cyclones, 15 named storms, 7 hurricanes, and 2 major hurricanes. The long-term 1971–2004 average suggests an average season to feature 15 named storms, 9 hurricanes, and 4 major hurricanes. October in particular was notably quiet, with the formation of only one tropical depression; only three other seasons, 1989, 1995, and 1996, ended the month without the designation of a named storm.[7]

Overall wind energy output was reflected with an Accumulated cyclone energy index value of 75 units, or about 66% of the long-term mean of 114 units, highlighting the generally weak and short-lived nature of tropical activity across the basin; at the time, this was the ninth lowest value on record. Analysis of the environment suggested that most storms formed during the passage of the positive Madden–Julian oscillation and its associated upper-air divergence, which is favorable for tropical cyclone formation. Extended reprieves in tropical activity were connected to upper-level convergence. Another factor that led to a below-average season was the presence of cooler than average ocean temperatures during the peak months, helping to extend the period of lesser activity that began throughout the eastern Pacific around 1995.[8] The 2005 became a record-tying most active in the month between 1966, 1992, 1994, 1997, later in 2019 forming six named storms in the basin

Systems

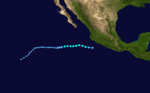

Hurricane Adrian

| Category 1 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | May 17 – May 21 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 80 mph (130 km/h) (1-min) 982 mbar (hPa) |

In early to mid-May, several areas of disturbed weather moving westward from Central America aided in the formation of a broad area of low pressure well south of Mexico. A poorly-defined tropical wave became intertwined with the larger system over subsequent days, leading to the formation of a tropical depression at 18:00 UTC on May 17. The nascent cyclone intensified into Tropical Storm Adrian six hours later. Despite the effects of moderate wind shear, the system steadily organized as convection became concentrated around the center, and Adrian attained its peak with winds of 80 mph (130 km/h) at 18:00 UTC on May 19. Environmental conditions became less conducive thereafter as downsloping from mountains along the coastline of Mexico combined with the already-marginal upper-level winds. The cyclone fell to tropical storm intensity at 00:00 UTC on May 20, tropical depression intensity at 18:00 UTC that day, and dissipated at 06:00 UTC on May 21 along the coastline of Honduras in the Gulf of Fonseca.[9]

Hurricane Adrian was responsible for five deaths: two died in a mudslide in Guatemala,[10] a pilot crashed in high winds and a person drowned in El Salvador,[11] and a person was killed by flooding in Nicaragua.[9] Heavy rainfall up to 16.4 in (418.4 mm) in El Salvador led to landslides, damaged roads, and flash flooding.[12] In Honduras, a few shacks were destroyed, a few roads were blocked, and some flooding occurred; similar effects were noted in Guatemala and Nicaragua.[13] Monetary losses topped $12 million (2005 USD) in El Salvador alone.[14]

Tropical Storm Beatriz

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | June 21 – June 24 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 50 mph (85 km/h) (1-min) 1000 mbar (hPa) |

A tropical wave emerged into the Atlantic on June 8 and entered the East Pacific over a week later, merging with a number of disturbances within a broad area of low pressure south of Mexico on June 17. The disturbance's cloud pattern—although initially elongated—steadily coalesced, leading to the formation of a tropical depression at 18:00 UTC on June 21 and further intensification into Tropical Storm Beatriz at 12:00 UTC on June 22. The system battled easterly wind shear and marginal ocean temperatures on its west-northwest track, attaining peak winds of 50 mph (85 km/h) the next day before weakening to tropical depression intensity at 00:00 UTC on June 24. Six hours later, it degenerated into a remnant low which slowed and turned southward prior to dissipating early on June 26.[15]

Tropical Storm Calvin

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | June 26 – June 29 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 50 mph (85 km/h) (1-min) 1000 mbar (hPa) |

A tropical wave emerged off the western coast of Africa on June 11, remaining inconspicuous until reaching the southwestern Caribbean Sea eight days later. The system entered the eastern Pacific on June 21, where steady organization led to the formation of a tropical depression around 06:00 UTC on June 26 while located 330 mi (530 km) south-southeast of Acapulco, Mexico. Upon formation, the cyclone moved north-northwest and then west-northwest under the dictation of a subtropical ridge to its north. It intensified into Tropical Storm Calvin at 18:00 UTC on June 26, attaining a peak intensity of 50 mph (85 km/h) early the next morning in conjunction with a well-defined spiral band on radar.[16][17] Calvin then dove west-southwest and weakened as strong wind shear exposed the storm's circulation; it fell to tropical depression status at 12:00 UTC on June 28 and further degenerated to a remnant low by 06:00 UTC the next day. The low moved generally westward before dissipating well southwest of the Baja California peninsula on July 3.[16] As a tropical cyclone, Calvin caused only minor damage to roofs and highways, flooded a house, and toppled two trees.[18]

Tropical Storm Dora

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | July 4 – July 6 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 45 mph (75 km/h) (1-min) 1002 mbar (hPa) |

The genesis of Tropical Storm Dora can be attributed to a westward-moving tropical wave that emerged off Africa on June 18. By July 3, the wave passed through the Gulf of Tehuantepec, where broad cyclonic flow began to develop along its axis. Following further organization, the disturbance intensified into a tropical depression by 00:00 UTC on July 4 and further strengthened into Tropical Storm Dora six hours later. The cyclone moved north-northwest and then west-northwest, paralleling the coastline of Mexico under the influence of a subtropical ridge,[19] where landslides and mudslides cut communication to 12 mountain villages.[20] Under a moderate easterly wind shear regime, Dora ultimately changed little in strength, peaking with winds of 45 mph (75 km/h) as the center became obscured on the eastern edge of extremely deep convection.[21] A track over colder waters caused the storm to fall to tropical depression intensity late on July 5 and degenerate into a remnant low by 12:00 UTC on July 6. The low then dissipated six hours later.[19]

Tropical Storm Eugene

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | July 18 – July 20 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 70 mph (110 km/h) (1-min) 989 mbar (hPa) |

A tropical wave first identified over the Caribbean Sea on July 10 entered the eastern Pacific four days later. The disturbance organized as banding features became distinct, leading to the formation of a tropical depression by 06:00 UTC on July 18. The cyclone intensified into Tropical Storm Eugene six hours later as a mid-level ridge steered it generally northwest. Amid an environment of light wind shear, Eugene steadily organized to reach peak winds of 70 mph (110 km/h) by late on July 19,[22] although it is possible the storm briefly attained hurricane intensity.[23] Already tracking over cooler waters, Eugene quickly weakened immediately after its peak, becoming a tropical depression by 12:00 UTC on July 20 and degenerating into a remnant low twelve hours later. The low continued northwest before losing its character on July 22.[22] As a tropical cyclone, Eugene flooded streets (which displaced six vehicles), left at least 30 houses inundated, and caused one death after a man's boat overturned.[24]

Tropical Depression One-C

| Tropical depression (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | August 3 – August 4 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 30 mph (45 km/h) (1-min) 1008 mbar (hPa) |

In late July to early August, an organized thunderstorm cluster persisted within the Intertropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ). Upon further development, the disturbance was designated as a tropical depression as it tracked swiftly west, the first and only cyclone to form in the central Pacific throughout the season. Despite initial forecasts of a minimal tropical storm, increasing wind shear and cooler ocean temperatures prompted the depression to instead dissipate by 00:00 UTC on August 5, having only attained peak winds of 30 mph (45 km/h).[25]

As a tropical cyclone, Tropical Depression One-C had no impact on land. However, the remnants of the depression dropped moderate to heavy rainfall in Hawaii, particularly on the Island of Hawaii. Rainfall totals measured up to 8.8 in (223.5 mm) in Glenwood, Hawaii.[25] Flash floods was reported in Kona and Ka‘ū, while minor flooding occurred in Hilo, Hamakua, and Kealakekua. In addition, minor street flooding was reported in several cities on that island; most notably, a nearly overflown drainage ditch threatened to submerge the Hawaii Belt Road.[26] Some coffee plants were damaged.[27]

Hurricane Fernanda

| Category 1 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | August 9 – August 16 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 85 mph (140 km/h) (1-min) 978 mbar (hPa) |

A vigorous tropical wave observed over western Africa in late July maintained vigor until passing the Windward Islands, becoming disorganized as it moved across South America and then into the eastern Pacific on August 5. Convection gradually redeveloped south of Mexico, leading to the formation of a tropical depression by 12:00 UTC on August 9 and intensification into Tropical Storm Fernanda twelve hours later. The nascent cyclone continued on a west-northwesterly course amid a favorable shear regime; it became a hurricane at 06:00 UTC on August 11 and attained peak winds of 85 mph (140 km/h) early the next day as a ragged eye became discernible. After leveling off in intensity, Fernanda fell to tropical storm intensity early on August 14, weakened to a tropical depression late on August 15, and degenerated into a remnant low by 06:00 UTC on August 16, all the while diving west-southwest. The low produced intermittent convection until dissipating the next day.[28]

Tropical Storm Greg

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | August 11 – August 15 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 50 mph (85 km/h) (1-min) 1000 mbar (hPa) |

A tropical wave that first crossed the western coastline of Africa on July 27 entered the eastern Pacific ten days later, gradually developing into a tropical depression by 06:00 UTC on August 11. The depression trekked west-northwest along the southern periphery of a subtropical ridge, intensifying into Tropical Storm Greg six hours after formation and reaching peak winds of 50 mph (85 km/h) by 00:00 UTC on August 12 as deep convection flared near the center and upper-level outflow became well established.[29][30] Northerly shear from nearby Fernanda and a nearby upper-level trough caused Greg to level off and maintain its status as a low-end tropical storm for several days as steering currents collapsed. Drifting south, stronger upper-level winds caused Greg to weaken to tropical depression intensity by 18:00 UTC on August 14 before degenerating into a remnant low by 00:00 UTC on August 16. The low was absorbed into the ITCZ shortly thereafter.[29]

Hurricane Hilary

| Category 2 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | August 19 – August 25 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 105 mph (165 km/h) (1-min) 970 mbar (hPa) |

A tropical wave moved off the western coast of Africa on August 4, eventually organizing into a tropical depression south of Mexico by 18:00 UTC on August 19. Twelve hours later, the depression intensified into Tropical Storm Hilary. The newly named system tracked west after formation, steered on the south side of a subtropical ridge. Favorable upper-level winds and warm ocean temperatures allowed it to quickly intensify, and Hilary became a hurricane by 00:00 UTC on August 21. After leveling off briefly, the cyclone attained its peak as a Category 2 hurricane with winds of 105 mph (185 km/h) early the next morning,[31] consistent with a ragged eye on infrared satellite imagery.[32] Hilary entered a progressively cooler ocean after peak, resulting in the loss of deep convection. The system fell to tropical storm intensity late on August 24, tropical depression intensity late on August 25, and degenerated to a remnant low by 00:00 UTC on August 26. The low moved generally west until dissipating early on August 28.[31]

Tropical Storm Irwin

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | August 25 – August 28 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 50 mph (85 km/h) (1-min) 1000 mbar (hPa) |

The formation of Irwin can be traced to a tropical wave that emerged off Africa on August 10. It continued west, fracturing into two portions near the Leeward Islands; the northern half aided in the formation of Hurricane Katrina, whereas the southern portion continued into the eastern Pacific. Steady organization led to the formation of a tropical depression by 12:00 UTC on August 25 and intensification into a tropical storm twelve hours later.[33] With the center located on the edge of deep convection,[34] Irwin attained peak winds of 50 mph (85 km/h) early on August 26 before northeasterly wind shear prompted weakening. The cyclone fell to tropical depression intensity early on August 28 and further degenerated to a remnant low by 18:00 UTC on August 28. The low moved west and then southwest until dissipating on September 3.[33]

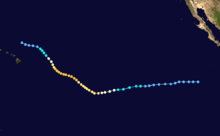

Hurricane Jova

| Category 3 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | September 12 – September 25 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 125 mph (205 km/h) (1-min) 951 mbar (hPa) |

A tropical wave emerged off the western coast of Africa on August 28. Similar to the setup that spawned Irwin, the northern half of the wave fractured and led to the formation of Hurricane Maria, whereas the southern part of the wave continued into the eastern Pacific on September 4. The disturbance initially changed little in organization; an increase in convection on September 12, however, aided in the formation of a tropical depression by 00:00 UTC that day. Affected by moderate easterly shear, the depression failed to intensify into Tropical Storm Jova until 00:00 UTC on September 15. The cyclone intensified at a faster rate thereafter, attaining hurricane intensity early the next day as it turned west-southwest. Jova crossed into the central Pacific early on September 18, where environmental conditions favored continued intensification. As the storm moved into the basin, it abruptly turned northwest toward a weakness in the subtropical ridge.[35]

Nearby dry air acted to temporarily but significantly weaken Jova's spiral banding despite a favorable upper-level environment.[36] By 12:00 UTC on September 19, however, it intensified into the first major hurricane – a Category 3 or larger on the Saffir–Simpson hurricane wind scale – of the season; twelve hours later, it attained peak winds of 125 mph (205 km/h). Cooler ocean temperatures took their toll on Jova as it progressed westward, with Jova falling to tropical storm intensity early on September 23, dropping to tropical depression intensity early on September 24, and ultimately dissipating by 06:00 UTC on September 25 a few hundred miles north of Hilo, Hawaii.[35]

Hurricane Kenneth

| Category 4 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | September 14 – September 30 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 130 mph (215 km/h) (1-min) 947 mbar (hPa) |

A tropical wave led to the formation of a tropical depression well southwest of the Baja California peninsula by 18:00 UTC on September 14. On a generally westward track, light wind shear and warm ocean temperatures allowed the depression to rapidly intensify, becoming Tropical storm Kenneth twelve hours after formation and further intensifying into a hurricane by 00:00 UTC on September 16.[37] The storm underwent an eyewall replacement cycle later that day,[38] temporarily halting the storm's development. By 06:00 UTC on September 17, however, Kenneth attained major hurricane status, and by 12:00 UTC the next morning, it attained its peak as a Category 4 hurricane with winds of 130 mph (215 km/h).[37]

Steering currents collapsed after peak, causing the storm to move erratically, but generally toward the west. Kenneth fell to tropical storm intensity late on September 20, but a brief reprieve in these winds allowed it to regain hurricane strength early on September 25. The hurricane entered the central Pacific on September 26 and weakened to a tropical storm again as south-southwesterly wind shear increased. After little change in strength for several days, Kenneth weakened to a tropical depression early on September 29 and ultimately dissipated just east of Hawaii by 00:00 UTC on September 31.[37] The remnants of Kenneth interacted with an upper-level trough, producing up to 12 in (305 mm) on Oahu. Lake Wilson and the Kaukonahua Stream both overflowed their banks as a result.[39] A few homes were flooded along Hawaii Route 61 by up to a foot of flowing water.[40] Waves of 8–10 ft (2–3 m) affected the coastline of the Hawaiian Islands.[41]

Tropical Storm Lidia

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | September 17 – September 19 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 40 mph (65 km/h) (1-min) 1005 mbar (hPa) |

In mid-September, a series of tropical waves entered the eastern Pacific from the Caribbean Sea. One of these waves led to the formation of a tropical depression by 12:00 UTC on September 17, which intensified into Tropical Storm Lidia and attained peak winds of 40 mph (65 km/h) six hours later.[42] Initial forecasts were of low confidence, with forecasters citing uncertainty in whether Lidia or a developing disturbance to its east would become the dominant cyclone.[43] Nearly stationary, the cyclone's cloud pattern soon became distorted by the much larger circulation of developing Tropical Storm Max. Lidia weakened to a tropical depression late on September 18 and was completely absorbed by Max twelve hours later.[42]

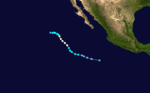

Hurricane Max

| Category 1 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | September 18 – September 22 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 85 mph (140 km/h) (1-min) 981 mbar (hPa) |

A tropical wave exited Africa on September 4, entering the eastern Pacific nine days later. The disturbance was initially slow to organize due to its broad nature, but finally began to show signs of organization early on September 18 as the system approached a stalled-out Tropical Storm Lidia. Remnants of Hurricane Max brought a weak cold front, heavy rainfall in Southern California on September 20. The system became a tropical depression by 12:00 UTC that day and intensified into Tropical Storm Max six hours later, simultaneously absorbing the weaker, much smaller Lidia. The storm turned northwest on the periphery of a subtropical ridge and continued to develop in a light wind shear environment. Max became a hurricane by 00:00 UTC on September 20 and attained peak winds of 85 mph (140 km/h) twelve hours later as a large but well-defined eye became apparent. It began steady weakening shortly thereafter as the storm entered cooler waters, falling to tropical storm intensity early on September 21 and further to tropical depression status early the next day as a mid-level ridge forced it back west. Max degenerated to a remnant low by 18:00 UTC on September 22, which then drifted south before dissipating on September 26.[44]

Tropical Storm Norma

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | September 23 – September 27 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 60 mph (95 km/h) (1-min) 997 mbar (hPa) |

An area of disturbed weather formed south of Mexico on September 19, followed by the formation of a broad area of low pressure within the disturbance two days later. A few small vortices were observed within the broad low over subsequent days, one of which cled to the formation of a tropical depression by 00:00 UTC on September 23. On a west-northwest course, the depression intensified into Tropical Storm Norma twelve hours later and ultimately attained peak winds of 60 mph (95 km/h) by 18:00 UTC on September 24 as the circulation became centrally located within the convection and banding features developed. Norma turned northwest as easterly wind shear increased, causing it to weaken to a tropical depression by 18:00 UTC on September 26 and degenerate to a remnant low a day later. The low turned south and east, persisting for several days before dissipating on October 1.[45]

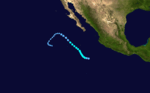

Hurricane Otis

| Category 2 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | September 28 – October 3 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 105 mph (165 km/h) (1-min) 970 mbar (hPa) |

A tropical wave moved off Africa on September 9, the northern half of which led to the formation of Hurricane Philippe. After emerging into the eastern Pacific nearly two weeks later, the system showed signs of organization, attaining tropical depression status by 00:00 UTC on September 28. It drifted west-southwest before turning northwest on September 29, at which time it intensified into Tropical Storm Otis. A favorable environment allowed the storm to become a hurricane early on September 30 and attain peak winds of 105 mph (165 km/h) by 06:00 UTC on October 1. Steering currents weakened after peak, allowing Otis to meander into cooler waters offshore the Baja California peninsula. It weakened to a tropical storm early on October 2, weakened to a tropical depression early on October 3, and degenerated to a remnant low by 00:00 UTC on October 4. The low drifted southwest and dissipated the next day.[46]

Although the center of Otis remained offshore, Cabo San Lucas recorded sustained winds of 49 mph (79 km/h), with gusts to 63 mph (101 km/h).[47] Periods of heavy rainfall resulted in minor flooding across the southern portions of the Baja California peninsula. Offshore, two ships reported tropical storm-force winds.[46]

Tropical Depression Sixteen-E

| Tropical depression (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | October 15 – October 20 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 35 mph (55 km/h) (1-min) 1005 mbar (hPa) |

The final tropical cyclone of the season developed from a tropical wave that emerged off Africa on September 28. The wave entered the eastern Pacific over two weeks later, still embedded within the ITCZ. Deep convection and a better defined circulation became established as the system detached from the feature, leading to the formation of a tropical depression by 00:00 UTC on October 15. Steered on the south side of the Mexican subtropical ridge, the depression organized as extremely deep convection burst over its center; this led to the formation of an eye-like feature on microwave imagery, and it is possible the depression briefly attained tropical storm intensity. Shortly thereafter, however, easterly wind shear exposed the low-level center, and the depression degenerated to a remnant low by 00:00 UTC on September 18.[48]

The remnant low continued westward, now steered by low-level easterly flow across the basin. Early on October 19, deep convection began to reform near the circulation, leading to the re-designation of a tropical depression by 12:00 UTC that day. Like its previous incarnation, however, a combination of dry air and southeasterly wind shear prevented the cyclone from intensifying to tropical storm status, with only a few curved band in its northern semicircle. Steady weakening occurred until the depression degenerated to a remnant low for a second time around 00:00 UTC on October 21. The remnant low turned southwestward before becoming reabsorbed into the ITCZ well southwest of the Baja California peninsula twelve hours later.[48]

Storm names

The following names were used for named storms that formed in the northeast Pacific in 2005. This is the same list that was used in the 1999 season. Names that were not assigned are marked in gray. There were no names retired by the WMO in the spring of 2006 despite a formal request by the Hawaii State Civil Defense for the name Kenneth;[49] therefore, the same list was reused in the 2011 season.[50]

|

|

For storms that form in the Central Pacific Hurricane Center's area of responsibility, encompassing the area between 140 degrees west and the International Date Line, all names are used in a series of four rotating lists. The next four names that were slated for use in 2005 are shown below, however none of them were used.[50]

|

|

|

|

Season effects

This is a table of all the storms that have formed in the 2005 Pacific hurricane season. It includes their duration, names, landfall(s), denoted in parentheses, damages, and death totals. Deaths in parentheses are additional and indirect (an example of an indirect death would be a traffic accident), but were still related to that storm. Damage and deaths include totals while the storm was extratropical, a wave, or a low, and all the damage figures are in 2005 USD.

| Saffir–Simpson scale | ||||||

| TD | TS | C1 | C2 | C3 | C4 | C5 |

| Storm name |

Dates active | Storm category

at peak intensity |

Max 1-min wind mph (km/h) |

Min. press. (mbar) |

Areas affected | Damage (USD) |

Deaths | Refs | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adrian | May 17 – 21 | Category 1 hurricane | 80 (130) | 982 | Guatemala, El Salvador, Nicaragua, Honduras | $12 million | 5 | |||

| Beatriz | June 21 – 24 | Tropical storm | 50 (85) | 1000 | None | None | None | |||

| Calvin | June 26 – 29 | Tropical storm | 50 (85) | 1000 | Southwestern Mexico | Minimal | None | |||

| Dora | July 4 – 6 | Tropical storm | 45 (75) | 1002 | Southwestern Mexico | Minimal | None | |||

| Eugene | July 18 – 20 | Tropical storm | 70 (110) | 989 | Baja California Peninsula | Minimal | 1 | |||

| One-C | August 3 – 4 | Tropical depression | 30 (45) | 1008 | None | None | None | |||

| Fernanda | August 9 – 16 | Category 1 hurricane | 85 (140) | 978 | None | None | None | |||

| Greg | August 11 – 15 | Tropical storm | 50 (85) | 1000 | None | None | None | |||

| Hilary | August 19 – 25 | Category 2 hurricane | 105 (165) | 970 | None | None | None | |||

| Irwin | August 25 – 28 | Tropical storm | 50 (85) | 1000 | Southwestern Mexico | None | None | |||

| Jova | September 12 – 25 | Category 3 hurricane | 125 (205) | 951 | None | None | None | |||

| Kenneth | September 14 – 30 | Category 4 hurricane | 130 (215) | 947 | Hawaii | None | None | |||

| Lidia | September 17 – 19 | Tropical storm | 40 (65) | 1005 | None | None | None | |||

| Max | September 18 – 22 | Category 1 hurricane | 85 (140) | 981 | None | None | None | |||

| Norma | September 23 – 27 | Tropical storm | 60 (95) | 997 | None | None | None | |||

| Otis | September 28 – October 3 | Category 2 hurricane | 105 (165) | 970 | Western Mexico, Baja California Sur | Minimal | None | |||

| Sixteen-E | October 15 – 20 | Tropical depression | 35 (55) | 1005 | None | None | None | |||

| Season aggregates | ||||||||||

| 17 systems | May 17 – October 20 | 130 (215) | 947 | $12 million | 6 | |||||

See also

- List of Pacific hurricanes

- Pacific hurricane season

- Tropical cyclones in 2005

- 2005 Atlantic hurricane season

- 2005 Pacific typhoon season

- 2005 North Indian Ocean cyclone season

- South-West Indian Ocean cyclone seasons: 2004–05, 2005–06

- Australian region cyclone seasons: 2004–05, 2005–06

- South Pacific cyclone seasons: 2004–05, 2005–06

References

- Christopher W. Landsea (June 1, 2016). "G: Tropical Cyclone Climatology". In Neal Dorst (ed.). Hurricane Research Division: Frequently Asked Questions. Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory. Miami, Florida: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. G1) When is hurricane season ?. Retrieved April 27, 2017.

- Carmeyia Gillis (May 16, 2005). NOAA Releases East Pacific Hurricane Season outlook (Report). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved April 26, 2017.

- Informe sobre el pronóstico de la temporada de ciclones del 2004 (Report) (in Spanish). Servicio Meteorológico Nacional. February 2005. Archived from the original on April 6, 2005. Retrieved April 26, 2017.

- National Hurricane Center; Hurricane Research Division; Central Pacific Hurricane Center. "The Northeast and North Central Pacific hurricane database 1949–2019". United States National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's National Weather Service. A guide on how to read the database is available here.

- Chris Vaccaro (May 16, 2005). NOAA Expects Below Average Central Pacific Hurricane Season (Report). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved April 26, 2017.

- Richard D. Knabb; James L. Franklin (June 1, 2005). Monthly Tropical Weather Summary: May (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved April 25, 2017.

- Stacy R. Stewart; John L. Beven II; James L. Franklin (November 1, 2005). Monthly Tropical Weather Summary: October (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved April 27, 2017.

- Knabb, Richard D.; Avila, Lixion A.; Beven, John L.; Franklin, James L.; Pasch, Richard J.; Stewart, Stacy R. (March 2008). "Eastern North Pacific Hurricane Season of 2005". Monthly Weather Review. 136 (3): 1201–1216. Bibcode:2008MWRv..136.1201K. doi:10.1175/2007MWR2076.1.

- Richard D. Knabb (November 24, 2005). Tropical Cyclone Report: Hurricane Adrian (PDF) (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. pp. 1, 2, 6. Retrieved March 11, 2017.

- "Storm floods, slides feared in Central America". NBC News. May 20, 2005. Retrieved April 25, 2017.

- "El Salvador, Honduras escape hurricane's wrath". CBC News. May 20, 2005. Retrieved April 25, 2017.

- Informe de los Deslizamientos de tierra generados por el Huracán Adrián, El Salvador (PDF) (Report) (in Spanish). Servicio Nacional de Estudios Territoriales. May 2005. Retrieved April 25, 2017.

- "Hurricane Adrian whacks El Salvador, then fizzles". USA Today. May 19, 2005. Retrieved April 25, 2017.

- Mayency Linares; Nadia Martínez. "Empresas pierden $12 millones" (in Spanish). La Prensa Gráfica. Retrieved April 25, 2017.

- James L. Franklin (July 23, 2005). Tropical Cyclone Report: Tropical Storm Beatriz (PDF) (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. pp. 1, 3. Retrieved March 17, 2017.

- Jack L. Beven II (November 28, 2005). Tropical Cyclone Report: Tropical Storm Calvin (PDF) (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. pp. 1, 3. Retrieved April 22, 2017.

- Richard J. Pasch (June 27, 2005). Tropical Storm Calvin Discussion Number 4 (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved April 22, 2017.

- Juan Cervantes Gómez (June 29, 2005). "Provoca 'Calvin' daños en carreteras" (in Spanish). El Universal. Retrieved April 27, 2017.

- Stacy R. Stewart (August 2, 2005). Tropical Cyclone Report: Tropical Storm Dora (PDF) (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. pp. 1, 3. Retrieved April 23, 2017.

- Juan Cervantes Gómez (July 5, 2005). "Daños en Guerrero por fuertes lluvias" (in Spanish). El Universal. Retrieved April 27, 2017.

- David P. Roberts; Richard J. Pasch (July 4, 2005). Tropical Depression Four-E Discussion Number 3 (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved April 23, 2017.

- Richard J. Pasch (April 5, 2006). Tropical Cyclone Report: Tropical Storm Eugene (PDF) (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. pp. 1, 3. Retrieved April 23, 2017.

- James L. Franklin (July 19, 2005). Tropical Storm Eugene Discussion Number 6 (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved April 23, 2017.

- "Dejan lluvias un muerto en Acapulco" (in Spanish). El Universal. July 18, 2005. Retrieved April 27, 2017.

- Andy Nash; Victor Proton; Robert Farrell; Roy Matsuda (May 2006). Overview of the 2005 Central North Pacific Tropical Cyclone Season (PDF) (Report). Honolulu, Hawaii: Central Pacific Hurricane Center. Retrieved June 9, 2019.

- August 2005 Precipitation Summary (Report). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. National Weather Service Weather Forecast Office in Honolulu, Hawaii. September 7, 2005. Archived from the original on August 18, 2007. Retrieved April 26, 2017.

- Hawaii Event Report: Heavy Rain (Report). National Centers for Environmental Information. National Weather Service Weather Forecast Office in Honolulu, Hawaii. 2005. Retrieved April 26, 2017.

- Lixion A. Avila (October 12, 2005). Tropical Cyclone Report: Hurricane Fernanda (PDF) (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. pp. 1, 3. Retrieved April 23, 2017.

- Richard D. Knabb (March 17, 2006). Tropical Cyclone Report: Tropical Storm Greg (PDF) (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. pp. 1, 4. Retrieved April 25, 2017.

- Richard D. Knabb (August 11, 2005). Tropical Storm Greg Discussion Number 4 (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved April 25, 2017.

- James L. Franklin (February 1, 2006). Tropical Cyclone Report: Hurricane Hilary (PDF) (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. pp. 1, 3. Retrieved April 25, 2017.

- John L. Beven II (August 22, 2005). Hurricane Hilary Discussion Number 13 (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved April 25, 2017.

- John L. Beven II (January 17, 2006). Tropical Cyclone Report: Tropical Storm Irwin (PDF) (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. pp. 1, 3. Retrieved April 25, 2017.

- Michelle Mainelli; Richard D. Knabb (August 26, 2005). Tropical Storm Irwin Discussion Number 3 (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved April 25, 2017.

- Stacy R. Stewart (February 27, 2006). Tropical Cyclone Report: Hurricane Jova (PDF) (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. pp. 1, 2, 4, 5. Retrieved April 25, 2017.

- Richard J. Pasch; David P. Roberts (April 25, 2017). "Hurricane Jova Discussion Number 25". Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 17, 2005.

- Richard J. Pasch (April 20, 2005). Tropical Cyclone Report: Hurricane Kenneth (PDF) (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. pp. 1, 2, 4, 5. Retrieved April 25, 2017.

- David P. Roberts; Stacy R. Stewart (September 16, 2005). Hurricane Kenneth Discussion Number 10 (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved April 25, 2017.

- Hawaii Event Report: Heavy Rain (Report). National Centers for Environmental Information. National Weather Service Weather Forecast Office in Honolulu, Hawaii. 2005. Retrieved April 27, 2017.

- Monthly Precipitation Summary (Report). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. November 3, 2005. Archived from the original on August 18, 2007. Retrieved April 27, 2017.

- Hawaii Event Report: High Surf (Report). National Centers for Environmental Information. National Weather Service Weather Forecast Office in Honolulu, Hawaii. 2005. Retrieved April 27, 2017.

- Lixion A. Avila (November 15, 2005). Tropical Cyclone Report: Tropical Storm Lidia (PDF) (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. pp. 1, 2. Retrieved April 25, 2017.

- Michelle Mainelli; John L. Beven II (September 17, 2005). Tropical Depression Twelve-E Discussion Number 1 (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved April 25, 2017.

- Richard D. Knabb (April 5, 2006). Tropical Cyclone Report: Hurricane Max (PDF) (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. pp. 1, 2, 4. Retrieved April 25, 2017.

- James L. Franklin; Eric S. Blake (January 23, 2006). Tropical Cyclone Report: Tropical Storm Norma (PDF) (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. pp. 1, 3. Retrieved April 25, 2017.

- Jack L. Beven II (January 18, 2006). Tropical Cyclone Report: Hurricane Otis (PDF) (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. pp. 1, 3. Retrieved April 25, 2017.

- Guillermo Arias (October 1, 2005). "Otis weakens to tropical storm". USA Today. Retrieved April 26, 2017.

- Stacy R. Stewart (September 10, 2005). Tropical Cyclone Report: Tropical Depression Sixteen-E (PDF) (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. pp. 1, 3. Retrieved April 25, 2017.

- 61st Interdepartmental Hurricane Conference (PDF) (Report). Office of the Federal Coordinator for Meteorological Services and Supporting Research. March 5, 2007. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 10, 2009. Retrieved April 27, 2017.

- "Tropical Cyclone Naming". World Meteorological Organization. Retrieved April 25, 2017.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to 2005 Pacific hurricane season. |