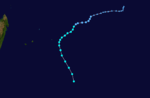

2004–05 South-West Indian Ocean cyclone season

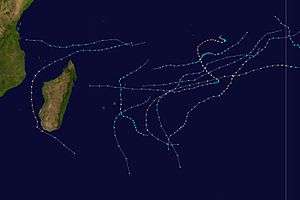

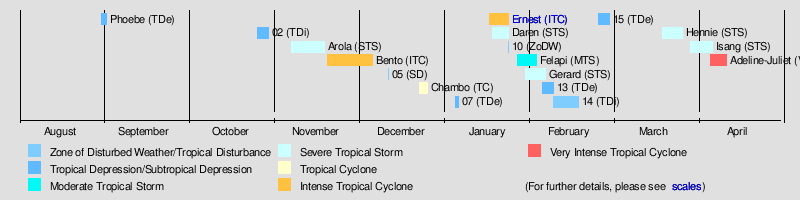

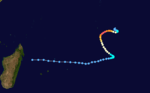

The 2004–05 South-West Indian Ocean cyclone season was a near average season, despite beginning unusually early on August 30 with the formation of an early-season tropical depression. Météo-France's meteorological office in Réunion (MFR) ultimately monitored 18 tropical disturbances during the season, of which 15 became tropical depressions. Two storms – Arola and Bento – formed in November, and the latter became the most intense November cyclone on record. Bento attained its peak intensity at a low latitude, and weakened before threatening land. Tropical Cyclone Chambo was the only named storm in December. In January, Severe Tropical Storm Daren and Cyclone Ernest existed simultaneously. The latter storm struck southern Madagascar, and five days later, Moderate Tropical Storm Felapi affected the same area; the two storms killed 78 people and left over 32,000 people homeless. At the end of January, Severe Tropical Storm Gerard existed as an unnamed tropical storm for 18 hours due to discrepancies between warning centers.

| 2004–05 South-West Indian Ocean cyclone season | |

|---|---|

Season summary map | |

| Seasonal boundaries | |

| First system formed | August 30, 2004 |

| Last system dissipated | April 11, 2005 |

| Strongest storm | |

| Name | Juliet |

| • Maximum winds | 220 km/h (140 mph) (10-minute sustained) |

| • Lowest pressure | 905 hPa (mbar) |

| Seasonal statistics | |

| Total disturbances | 18, 1 unofficial |

| Total depressions | 15, 1 unofficial |

| Total storms | 10, 1 unofficial |

| Tropical cyclones | 4 |

| Intense tropical cyclones | 3 |

| Very intense tropical cyclones | 1 |

| Total fatalities | 78 total |

| Total damage | Unknown |

| Related articles | |

After a series of weak tropical systems in February, there were two storms in March. Severe Tropical Storm Hennie brought heavy rainfall to the Mascarene Islands, and Severe Tropical Storm Isang remained away from land. The season's strongest storm originated in the neighboring Australian basin, developing in early April near the Cocos Islands. After being named Adeline by the Australian Bureau of Meteorology (BoM), the MFR renamed the storm Juliet once the storm crossed 90°E. Juliet would reach maximum sustained winds of 220 km/h (140 mph), making it a very intense tropical cyclone. Juliet damaged corn plantations on the island of Rodrigues before becoming an extratropical cyclone on April 11, thus ending the season.

Seasonal summary

Météo-France's meteorological office in Réunion (MFR) is the official Regional Specialized Meteorological Center for the South-West Indian Ocean, tracking all tropical cyclones from the east coast of Africa to 90° E.[1] The agency tracked 18 tropical disturbances, including one zone of disturbed weather that lasted for one advisory, which was higher than normal. The agency assessed that 15 disturbances reached tropical depression intensity.[2][3] Ten of these weather systems intensified into named storms, which was one higher than normal. There were 44 days in which a named storm was active, lower than the average of 53. There was an unusual period of inactivity across much of the basin from January to March, typically the most active months. During this time, the intertropical convergence zone was located farther south than usual, causing any developing storms to reach their peak intensity at higher latitudes. The exception was southern Madagascar, which was affected by Cyclone Ernest and Tropical Storm Felapi in a five-day span in late January. Four of the named storms attained maximum sustained winds of at least 120 km/h (75 mph), the threshold for tropical cyclone intensity; this was also near normal. Three tropical cyclones strengthened into intense tropical cyclones, including Very Intense Tropical Cyclone Juliet.[2]

In addition to the MFR, the American-based Joint Typhoon Warning Center issued warnings for cyclones in the basin, as well as the entire southern hemisphere. The agency did not track Tropical Storm Felapi, and it estimated that a tropical depression in October attained tropical storm status.[4]

Systems

Severe Tropical Storm Arola

| Severe tropical storm (MFR) | |

| Category 1 tropical cyclone (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | November 6 – November 18 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 110 km/h (70 mph) (10-min) 978 hPa (mbar) |

The near-equatorial trough spawned an area of convection east of Diego Garcia on November 6, which the MFR classified as a tropical disturbance. The system slowly organized amid favorable conditions, including low to moderate wind shear. On November 8, the MFR upgraded the system to a tropical depression and later Moderate Tropical Storm Arola, and the JTWC classified it as Tropical Cyclone 03S. Steered by a ridge to the south, Arola moved southwestward at first while quickly intensifying. Late on November 8, the MFR estimated peak winds of 110 km/h (70 mph), making Arola a severe tropical storm. Early the next day, the JTWC upgraded the storm to the equivalent of a minimal hurricane, estimating peak winds of 120 km/h (75 mph). The storm turned to a westward drift, entering an area of higher wind shear and cooler waters, which caused Arola to weaken. On November 12, the MFR downgraded the storm to a tropical depression, by which time the storm was moving southwestward again, passing south of Diego Garcia. The JTWC discontinued advisories the next day. The MFR tracked Arola until November 18.[5][6][4][7]

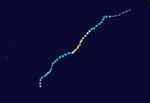

Intense Tropical Cyclone Bento

| Intense tropical cyclone (MFR) | |

| Category 5 tropical cyclone (SSHWS) | |

.jpg)  | |

| Duration | November 19 – December 3 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 215 km/h (130 mph) (10-min) 915 hPa (mbar) |

On the same day that Arola dissipated, the near-equatorial trough spawned another area of convection east of Diego Garcia.[5] A day later, the MFR classified the system as a tropical disturbance as the thunderstorms organized and consolidated, amid favorable conditions. On November 20, the MFR upgraded the system to Tropical Storm Bento, and the JTWC initiated advisories as Tropical Cyclone 04S. At first, Bento drifted to the southeast, but turned to the west two days later. The MFR upgraded the storm to tropical cyclone status on November 22, the same day that the storm began a rapid intensification phase. On November 23, the MFR estimated peak 10 minute winds of 215 km/h (130 mph), and the JTWC estimated peak 1 minute winds of 260 km/h (160 mph), equivalent to a Category 5 on the Saffir-Simpson scale. This made Bento among the most intense tropical cyclones in the basin within 10º of the equator, only surpassed by Cyclone Fantala in April 2016.[4][8][7][9] It also made Bento the strongest cyclone in the basin in the month of November, surpassing Cyclone Agnielle in 1995.[2]

Around its time of peak intensity, Bento was located far away from land – about 325 km (200 mi) east-southeast of Diego Garcia. It was also moving southwestward due to a ridge to its southeast. On November 24, the cyclone began weakening due to an eyewall replacement cycle, as well as the presence of drier air and increased wind shear. A day later, Bento turned to the southeast, steered by a passing trough. The MFR downgraded the cyclone to tropical storm status on November 26, but upgraded it back to tropical cyclone status a day later. By late on November 27, the circulation was exposed from the convection. Bento turned to the west and failed to reintensify due to cooler waters. The JTWC discontinued advisories on November 29, but the MFR continued tracking the system as a tropical disturbance until December 3, when Bento was passing north of the Mascarene Islands.[5][4][8][7]

Tropical Cyclone Chambo

| Tropical cyclone (MFR) | |

| Category 3 tropical cyclone (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | December 22 – December 30 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 155 km/h (100 mph) (10-min) 950 hPa (mbar) |

In the middle of December, the near-equatorial trough spawned an area of convection to the west of Indonesia. For several days, the system drifted westward through an area of minimal wind shear. On December 22, the MFR classified the system as Tropical Disturbance 6 to the northwest of the Cocos Islands. By that time, the thunderstorms were increasing and consolidating. The JTWC classified the system as Tropical Cyclone 06S on December 23. On the next day, the MFR upgraded the system to Moderate Tropical Storm Chambo. The storm quickly intensified as it moved southwestward, steered by a ridge to its southeast. On December 25, the MFR upgraded Chambo to tropical cyclone status, and the next day estimated peak 10 minute winds of 155 km/h (100 mph). The JTWC meanwhile estimated peak 1 minute winds of 195 km/h (120 mph). Cooler waters and stronger wind shear caused Chambo to begin weakening on December 27. By the next day, the circulation became exposed from the thunderstorms, and the JTWC discontinued advisories. On December 30, the MFR reclassified Chambo as an extratropical cyclone. The storm turned to the south and later southeast, and was last mentioned by the MFR on January 2.[10][11][12]

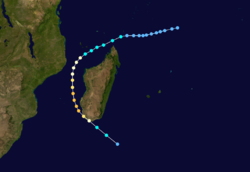

Intense Tropical Cyclone Ernest

| Intense tropical cyclone (MFR) | |

| Category 3 tropical cyclone (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | January 16 – January 23 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 165 km/h (105 mph) (10-min) 950 hPa (mbar) |

An area of convection developed west of Diego Garcia on January 16, prompting the MFR to classify it as Tropical Disturbance 8. A day later, the agency briefly discontinued advisories, only to resume them on January 19 as the disturbance passed north of Madagascar. That day, the JTWC classified the system as Tropical Cyclone 12S. On January 20, the MFR upgraded the system to Tropical Storm Ernest to the east of the Comoros. The storm quickly intensified, and within 12 hours of being named, the MFR upgraded Ernest to tropical cyclone status. The cyclone turned to the south through the Mozambique Channel, attaining peak winds of 165 km/h (105 mph) on January 22, according to the MFR. The JTWC estimated peak 1 minute winds of 185 km/h (115 mph). On the next day, Ernest turned southeast and made landfall in extreme southern Madagascar, near Itampolo. It quickly emerged over open waters and weakened. On January 24, the MFR reclassified Ernest as an extratropical cyclone, tracking it for one more day.[3][4][2][13]

In southern Madagascar, Ernest produced high wind gusts, reaching 180 km/h (110 mph) in Toliara. The same town recorded heavy rainfall during the storm's passage, totaling 237.2 mm (9.34 in) over 24 hours. Ernest's Madagascar impacts were followed by Tropical Storm Felapi five days later.[2] Ernest killed 78 people in Madagascar.[14] Collectively, Ernest and Felapi damaged 5,792 buildings, which left 32,191 people homeless.[2] Madagascar's National Emergency Centre deployed workers to do search and rescue missions and provide water to storm victims.[15] The World Food Programme provided 45 tons of rice to affected residents, although persistent flooding disrupted relief work.[16]

Severe Tropical Storm Daren

| Severe tropical storm (MFR) | |

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | January 17 – January 23 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 95 km/h (60 mph) (10-min) 985 hPa (mbar) |

An area of thunderstorms formed on January 13 to the northwest of the Cocos Islands in the Australian basin. The system moved westward and organized gradually, hampered by strong wind shear. On January 17, the MFR classified the system as Tropical Disturbance 9 to the east of Diego Garcia. On the next day, the JTWC classified the disturbance as Tropical Cyclone 11S. The nascent system intensified into Tropical Storm Daren on January 19, reaching peak 10 minute winds of 95 km/h (60 mph) that day according to the MFR. The JTWC meanwhile estimated peak 1 minute winds of 85 km/h (50 mph). Steered by a ridge to its southeast, Daren moved southwestward and failed to intensify further. After encountering stronger wind shear, Daren weakened, and its circulation became exposed from the thunderstorms. The JTWC discontinued advisories on January 20. On the next day, the MFR downgraded Daren to a tropical depression while the system was passing north of Rodrigues. The MFR continued tracking Daren until January 23, when the disturbance was passing north of Mauritius.[3][17]

Moderate Tropical Storm Felapi

| Moderate tropical storm (MFR) | |

| |

| Duration | January 26 – February 3 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 65 km/h (40 mph) (10-min) 995 hPa (mbar) |

Three days after Cyclone Ernest exited the Mozambique Channel, an area of convection developed in the region, which the MFR classified as a tropical disturbance on January 26. The system organized while moving toward western Madagascar. On January 27, the MFR upgraded it to Moderate Tropical Storm Felapi, estimating peak winds of 65 km/h (40 mph). That day, Felapi moved ashore near Toliara, and quickly weakened back to tropical depression status. The system emerged near the southeast coast of Madagascar and turned to the northeast, transitioning into a subtropical cyclone. On January 31, Felapi turned to the south, and re-intensified to its former peak intensity as a subtropical depression. The storm weakened again and accelerated to the southeast. The MFR continued tracking Felapi until February 3.[3][18] The JTWC did not issue advisories on the storm.[3]

In southern Madagascar, Felapi dropped additional rainfall following Cyclone Ernest. Rainfall in Morondava reached 157.2 mm (6.19 in). Winds on the island reached 61 km/h (38 mph) inland at Ranohira.[2]

Severe Tropical Storm Gerard

| Severe tropical storm (MFR) | |

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | January 29 – February 5 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 115 km/h (70 mph) (10-min) 973 hPa (mbar) |

An area of convection persisted east of Diego Garcia on January 27. The system moved west-southwestward, with its circulation displaced from the thunderstorms due to strong wind shear and cooler air. The MFR classified the system as a tropical disturbance on January 29 and upgraded it to a tropical depression the next day, only to downgrade it again to a disturbance on January 31, after nearly all thunderstorms diminished. For several days, the weak system drifted southwestward toward the Mascarene Islands, steered by a ridge to the southeast. On February 2, thunderstorm activity increased as the system passed over Rodrigues, although the structure resembled a monsoon depression more commonly found in the Western Pacific Ocean. Over the next day, the structure became more akin to a tropical cyclone, with increasing convection and an eye-like feature near the center.[19][2][20]

On February 3, the JTWC initiated advisories on Tropical Cyclone 14S, and the MFR upgraded the depression to a moderate tropical storm. Ordinarily, this would result in the system being named; however, the Mauritius Meteorological Services responsible for naming believed it had not yet attained such intensity. For about 15 hours, the unnamed tropical storm intensified while accelerating to the south due to a passing trough. At 03:00 UTC on February 4, the Mauritius Meteorological Services named the storm Gerard. Shortly thereafter, the MFR estimated peak winds of 115 km/h (70 mph), just shy of tropical cyclone status, and similar to the JTWC estimate of 110 km/h (70 mph). The MFR noted uncertainty in the peak winds, due to the fast forward speed and small size. On February 5, Gerard rapidly weakened as it transitioned into an extratropical cyclone.[19][4][2] In the report to the WMO, the MFR noted that "for a tropical depression system of such intensity not to be named is unprecedented in the recent history of the basin."[2]

Severe Tropical Storm Hennie

| Severe tropical storm (MFR) | |

| Category 1 tropical cyclone (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | March 19 – March 26 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 100 km/h (65 mph) (10-min) 978 hPa (mbar) |

After a period of inactivity lasting about three weeks, a tropical disturbance formed on March 19 to the west of Diego Garcia. With low wind shear, the system developed a broad area of rotating thunderstorms. It moved southwestward, steered by a ridge to the southeast. The JTWC initiated advisories on the system late on March 21 as Tropical Cyclone 24S. On the next day, the MFR upgraded the disturbance to a tropical depression, and the Mauritius Meteorological Services named the system Hennie due to the threat to the Mascarene Islands. The MFR upgraded Hennie to a moderate tropical storm on March 23, and by that time the storm was moving southward. On March 24, Hennie passed about 140 km (85 mi) east of Mauritius. That day, the MFR estimated peak 10 minute winds of 100 km/h (65 mph), making Hennie a severe tropical storm. The JTWC estimated peak 1 minute winds of 120 km/h (75 mph), equivalent to a minimal hurricane. After passing the Mascarene Islands, Hennie turned to the southeast, entering an area of cooler, drier air. The circulation became exposed from the convection on March 26. On the next day, the MFR reclassified Hennie as an extratropical cyclone, and continued to track the storm for several more days as it accelerated southeastward. The MFR last mentioned the remnants of Hennie on April 1 when the storm was located over the far southeastern Indian Ocean.[21][4][22]

The storm dropped heavy rainfall in the Mascarene Islands, including a 24-hour precipitation total of 397 mm (15.6 in) in the mountainous peaks of Réunion. Rainfall on Mauritius reached 202.8 mm (7.98 in) at Sans-Souci.[21] The rains caused flooding on Mauritius,[2] resulting in the closure of airports and ports.[23]

Severe Tropical Storm Isang

| Severe tropical storm (MFR) | |

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | March 29 – April 6 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 115 km/h (75 mph) (10-min) 970 hPa (mbar) |

On March 29, an area of convection formed east-southeast of Diego Garcia and consolidated around a broad developing circulation. That day, the MFR designated the system as Tropical Disturbance 17. For several days, the system waxed and waned in organization as it drifted to the west-southwest. On April 3, the thunderstorms increased and organized around the center, prompting the MFR to upgrade the system to Moderate Tropical Storm Isang. That day, the JTWC initiated advisories on Tropical Cyclone 25S, located south of Diego Garcia and northeast of Rodrigues. The storm moved around the ridge to its southeast, intensifying slowly due to dry air in the region. On April 5, Isang turned to the south-east, and the thunderstorms became more organized, developing an eye-like feature. On the next day, the MFR estimated peak 10 minute winds of 115 km/h (70 mph), and the JTWC estimated peak 1 minute winds of 100 km/h (65 mph). Soon after reaching peak intensity, Isang encountered stronger wind shear and cold, dry air, which resulted in weakening. The MFR re-classified the storm as an extratropical cyclone on April 7, and continued tracking Isang for another day.[24][25]

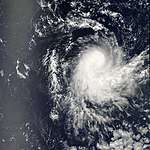

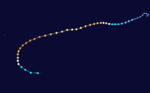

Very Intense Tropical Cyclone Adeline-Juliet

| Very intense tropical cyclone (MFR) | |

| Category 4 tropical cyclone (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | April 5 (Crossed 90°E) – April 11 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 220 km/h (140 mph) (10-min) 905 hPa (mbar) |

The near-equatorial trough spawned a circulation in the Australian region on April 2 to the east of the Cocos Islands. The BoM upgraded the system to Tropical Cyclone Adeline on April 3 while the storm was passing south of the islands. Continuing westward, the storm intensified further, reaching the equivalent of tropical cyclone status on April 4. On the same day, the JTWC classified the storm as Tropical Cyclone 26S. On April 5, Adeline crossed 90°E into the South-West Indian Ocean, whereupon the Mauritius Meteorological Service renamed the storm Juliet. The cyclone intensified further to an intense tropical cyclone on April 6, reaching 10 minute winds of 185 km/h (115 mph) before weakening.[26][4][24][27]

Cyclone Juliet began re-intensifying on April 8, by which time the storm had begun moving to the west-southwest. On April 9, the MFR upgraded Juliet to a very intense tropical cyclone, estimating peak 10 minute winds of 220 km/h (140 mph).[24][27] This would be the last very intense tropical cyclone until Edzani in 2010.[28] The JTWC estimated slightly higher 1 minute winds of 230 km/h (145 mph). On April 10, Juliet turned toward the south, passing about 215 km (135 mi) east-southeast of Rodrigues.[24][27] On the island, the cyclone's strong winds heavily damaged 15 corn plantations.[29] After passing Rodrigues, the cyclone weakened due to drier air, cooler waters, and higher wind shear, causing the circulation to become exposed from the convection. Juliet weakened below tropical cyclone status on April 12 while accelerating to the southeast. On the same day, the MFR reclassified the storm as extratropical. The agency followed Juliet until April 16.[24][27]

Other storms

On August 30, an area of low pressure developed near the edge of Météo-France's area of responsibility within an unseasonably active monsoonal band which coincided with the Madden–Julian oscillation. Tracking towards the southeast, the low experienced strong deep-level wind shear which kept most of the convection displaced from the center of circulation. On August 31, convection managed to develop around the west and southwestern portions of the low,[30] and was designated as Tropical Depression 01.[31] The depression reached its peak intensity at this time with winds of 55 km/h (35 mph 10-minute winds) and a minimum pressure of 999 hPa (mbar).[32] Shortly after, the depression entered Australian Bureau of Meteorology in Perth's area of responsibility. The depression later intensified into a tropical cyclone and was named Phoebe.[30]

Toward the end of October, low pressure areas developed on both sides of the equator in the west-central Indian Ocean. The system in the North Indian Ocean failed to develop, but the southern hemisphere system became Tropical Disturbance 02 on October 25. Moving westward, the disturbance had an organized area of thunderstorms near the center, with favorable conditions provided by the subtropical ridge. The MFR upgraded the disturbance to a depression on October 26, and briefly downgraded the system after the circulation became exposed, only to upgrade it again to a depression the next day. The JTWC initiated warnings on the system as Tropical Cyclone 02S on October 27, estimating 1 minute winds of 65 km/h (40 mph). That day, the system passed about 370 km (230 mi) north of Madagascar. Wind shear in the region caused the storm to weaken again. On October 29, the weak disturbance moved ashore in eastern Tanzania near Dar es Salaam, dropping heavy rainfall.[33]

On December 11, the MFR issued two bulletins for Subtropical Depression 05. The system formed about halfway between the southern tip of Madagascar, and failed to intensify.[10] On January 4, the MFR began issuing warnings on Tropical Depression 7 in the Mozambique Channel. The system moved southeastward, moving ashore western Madagascar between Morombe and Toliara on January 5, and quickly dissipated. Later in the month, the MFR issued one warning for Zone of Disturbed Weather 10, located well to the southeast of Diego Garcia.[3]

In February, there was a series of three week disturbances. Tropical Depression 13 formed on February 4 to the north of Mauritius. It moved southwestward and failed to intensify beyond winds of 55 km/h (35 mph). The depression passed just east of Mauritius on February 6, and became extratropical two days later. On the same day, Tropical Disturbance 14 formed to the northwest of Mauritius. For two days the system drifted westward before turning back to the east, reaching a point northeast of Mauritius on February 13. The disturbance then turned to the west-southwest, and was tracked by the MFR until February 17. On February 24, Tropical Disturbance 15 formed east of Diego Garcia. It drifted southward and intensified into a tropical depression on February 26, but dissipated two days later.[19]

In late November, Cyclone Agni from the North Indian Ocean crossed into the South-west Indian Ocean from the Northern Hemisphere while retaining its anticyclonic circulation, which is unusual due to the Coriolis effect being nonexistent along the equator. Its track was disputed and the JTWC instead assessed it as reaching as far south as 0.5 degrees north. It later crossed back into the Northern Hemisphere although its remnants later reentered the Southern Hemisphere while paralleling the Somalian coastline before dissipating shortly after.

Storm names

A tropical disturbance is named when it reaches moderate tropical storm strength. If a tropical disturbance reaches moderate tropical storm status west of 55°E, then the Sub-regional Tropical Cyclone Advisory Centre in Madagascar assigns the appropriate name to the storm. If a tropical disturbance reaches moderate tropical storm status between 55°E and 90°E, then the Sub-regional Tropical Cyclone Advisory Centre in Mauritius assigns the appropriate name to the storm. A new annual list is used every year so no names are retired.[34]

|

|

|

See also

References

- Philippe Caroff; et al. (April 2011). Operational procedures of TC satellite analysis at RSMC La Reunion (PDF) (Report). World Meteorological Organization. pp. 4–5. Retrieved 2013-10-27.

- RA I Tropical Cyclone Committee for the South-West Indian Ocean Seventeenth Session (PDF) (Report). World Meteorological Organization. 2005. Retrieved January 16, 2019.

- Gary Padgett (May 17, 2005). "Monthly Global Tropical Cyclone Summary January 2005". Retrieved January 16, 2019.

- Annual Tropical Cyclone Report (PDF) (Report). Joint Typhoon Warning Center. Retrieved January 15, 2019.

- Darwin Regional Specialised Meteorological Centre (November 2004). "Darwin Tropical Diagnostic Statement" (PDF). Bureau of Meteorology: 2. Retrieved January 15, 2019. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Kenneth R. Knapp; Michael C. Kruk; David H. Levinson; Howard J. Diamond; Charles J. Neumann (2010). 2005 Arola (2004312S05085). The International Best Track Archive for Climate Stewardship (IBTrACS): Unifying tropical cyclone best track data (Report). Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society. Archived from the original on January 16, 2019. Retrieved January 15, 2019.

- Gary Padgett (May 17, 2005). "Monthly Global Tropical Cyclone Summary November 2004". Retrieved January 16, 2019.

- Kenneth R. Knapp; Michael C. Kruk; David H. Levinson; Howard J. Diamond; Charles J. Neumann (2010). 2005 Bento (2004325S06078). The International Best Track Archive for Climate Stewardship (IBTrACS): Unifying tropical cyclone best track data (Report). Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society. Archived from the original on January 16, 2019. Retrieved January 15, 2019.

- Review of the 2015/2016 and 2016/2017 Cyclone Seasons (DOCX) (Report). World Meteorological Organization. Retrieved January 15, 2019.

- Gary Padgett (May 17, 2005). "Monthly Global Tropical Cyclone Summary December 2004". Retrieved January 16, 2019.

- Kenneth R. Knapp; Michael C. Kruk; David H. Levinson; Howard J. Diamond; Charles J. Neumann (2010). 2005 Chambo (2004357S06095). The International Best Track Archive for Climate Stewardship (IBTrACS): Unifying tropical cyclone best track data (Report). Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society. Archived from the original on January 17, 2019. Retrieved January 16, 2019.

- Darwin Regional Specialised Meteorological Centre (December 2004). "Darwin Tropical Diagnostic Statement" (PDF). Bureau of Meteorology: 2. Retrieved January 15, 2019. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Kenneth R. Knapp; Michael C. Kruk; David H. Levinson; Howard J. Diamond; Charles J. Neumann (2010). 2005 Ernest (2005017S09061). The International Best Track Archive for Climate Stewardship (IBTrACS): Unifying tropical cyclone best track data (Report). Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society. Archived from the original on January 17, 2019. Retrieved January 16, 2019.

- Université Catholique de Louvain (2014). "EM-DAT: The OFDA/CRED International Disaster Database for North America". Archived from the original on 2008-08-11. Retrieved 2014-03-04.

- "Cyclone Ernest kills three in Madagascar". IOL News. Agence France-Presse. January 31, 2005. Retrieved August 14, 2012.

- "Madagascar receives cyclone aid". Afrol News. 2005-02-01. Retrieved 2012-08-14.

- Kenneth R. Knapp; Michael C. Kruk; David H. Levinson; Howard J. Diamond; Charles J. Neumann (2010). 2005 Daren (2005015S06089). The International Best Track Archive for Climate Stewardship (IBTrACS): Unifying tropical cyclone best track data (Report). Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society. Archived from the original on January 17, 2019. Retrieved January 16, 2019.

- Kenneth R. Knapp; Michael C. Kruk; David H. Levinson; Howard J. Diamond; Charles J. Neumann (2010). 2005 Felapi (2005026S20040). The International Best Track Archive for Climate Stewardship (IBTrACS): Unifying tropical cyclone best track data (Report). Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society. Archived from the original on January 23, 2019. Retrieved January 22, 2019.

- "Monthly Global Tropical Cyclone Summary February 2005". May 17, 2005. Retrieved January 22, 2019.

- Kenneth R. Knapp; Michael C. Kruk; David H. Levinson; Howard J. Diamond; Charles J. Neumann (2010). 2005 Gerard (2005029S11072). The International Best Track Archive for Climate Stewardship (IBTrACS): Unifying tropical cyclone best track data (Report). Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society. Archived from the original on January 23, 2019. Retrieved January 16, 2019.

- Gary Padgett (2006-12-27). "Monthly Global Tropical Cyclone Summary March 2005". Retrieved December 13, 2018.

- Kenneth R. Knapp; Michael C. Kruk; David H. Levinson; Howard J. Diamond; Charles J. Neumann (2010). 2005 Hennie (2005079S10067). The International Best Track Archive for Climate Stewardship (IBTrACS): Unifying tropical cyclone best track data (Report). Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society. Archived from the original on January 23, 2019. Retrieved January 22, 2019.

- "Mauritius sea, airports reopen". News 24. March 24, 2005. Retrieved January 22, 2019.

- Gary Padgett (June 1, 2005). "Monthly Global Tropical Cyclone Summary April 2005". Retrieved January 22, 2019.

- Kenneth R. Knapp; Michael C. Kruk; David H. Levinson; Howard J. Diamond; Charles J. Neumann (2010). 2005 Isang (2005089S10085). The International Best Track Archive for Climate Stewardship (IBTrACS): Unifying tropical cyclone best track data (Report). Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society. Archived from the original on January 23, 2019. Retrieved January 22, 2019.

- "Tropical Cyclone Adeline" (PDF). Australian Bureau of Meteorology. Retrieved January 22, 2019.

- Kenneth R. Knapp; Michael C. Kruk; David H. Levinson; Howard J. Diamond; Charles J. Neumann (2010). 005 Adeline:Juliet (2005092S11102). The International Best Track Archive for Climate Stewardship (IBTrACS): Unifying tropical cyclone best track data (Report). Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society. Archived from the original on January 23, 2019. Retrieved January 22, 2019.

- Cyclone Season South-West Indian Ocean 2009 -2010 (PDF) (Report). RSMC Météo-France. p. 38. Retrieved January 22, 2019.

- Agricultural Cost of Production Survey 2005 (PDF) (Report). Republic of Mauritius Central Statistics Office. March 2008. p. 101. Retrieved December 13, 2018.

- Gary Padgett (January 27, 2005). "Monthly Tropical Cyclone Summary for September 2004". Typhoon 2000. Retrieved February 12, 2009.

- Gary Padgett (December 7, 2004). "Monthly Tropical Cyclone Summary for August 2004". Typhoon 2000. Retrieved February 12, 2009.

- Gary Padgett (October 24, 2004). "Monthly Tropical Cyclone Tracks for September 2004". Typhoon 2000. Retrieved February 12, 2009.

- Gary Padgett (May 17, 2005). "Monthly Global Tropical Cyclone Tracks October 2004". Retrieved January 15, 2019.

- "Fact Sheet Tropical Cyclone Names" (PDF). World Meteorological Organization. July 1, 2005. p. 4. Retrieved January 22, 2019.