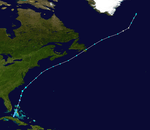

1937 Atlantic hurricane season

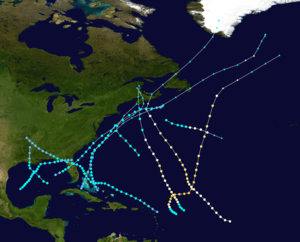

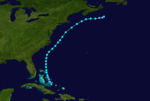

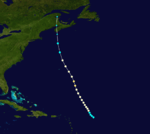

The 1937 Atlantic hurricane season was a below-average period of tropical cyclone activity in the North Atlantic, featuring eleven tropical storms; of these, four became hurricanes. One hurricane reached major hurricane intensity, equivalent to a Category 3 or higher on the modern Saffir–Simpson scale. The United States Weather Bureau defined the season as officially lasting from June 16 to October 16.[1][2] Tropical cyclones that did not approach populated areas or shipping lanes, especially if they were relatively weak and of short duration, may have remained undetected. Because technologies such as satellite monitoring were not available until the 1960s, historical data on tropical cyclones from this period are often not reliable. As a result of a reanalysis project which analyzed the season in 2012, a tropical storm and a hurricane were added to the Atlantic hurricane database (HURDAT). The official intensities and tracks of all storms were also revised by the reanalysis. The year's first storm formed on July 29 in the Gulf of Mexico, and the final system, a hurricane, dissipated over open ocean on October 21.

| 1937 Atlantic hurricane season | |

|---|---|

Season summary map | |

| Seasonal boundaries | |

| First system formed | July 29, 1937 |

| Last system dissipated | October 21, 1937 |

| Strongest storm | |

| Name | Six |

| • Maximum winds | 125 mph (205 km/h) |

| • Lowest pressure | 951 mbar (hPa; 28.08 inHg) |

| Seasonal statistics | |

| Total depressions | 16 |

| Total storms | 11 |

| Hurricanes | 4 |

| Major hurricanes (Cat. 3+) | 1 |

| Total fatalities | 20 |

| Total damage | ≥ $1.56 million (1937 USD) |

| Related article | |

| |

Most of the season's storms arose from the subtropics. Nova Scotia was a focus for storm activity with four storms reaching the Canadian province as extratropical cyclones. Two of these were the remnants of hurricanes; the first inflicted $1.5 million in damage on the apple crop in the Annapolis Valley, and the second tore up four breakwaters and sank or grounded several ships. The year's deadliest tropical cyclone was a tropical storm that struck Florida at the end of August. A squall associated with the storm caused the sinking of the SS Tarpon, killing 18 people. A short-lived tropical storm in October caused the wettest 48-hour period in the history of New Orleans, Louisiana, with 16.65 in (423 mm) of rainfall, causing the city's most destructive flood since the Great Mississippi Flood of 1927. A tropical storm striking parts of the U.S. Gulf Coast caused two deaths, but otherwise did minor damage. The season's strongest storm was estimated to have produced maximum sustained winds of 125 mph (205 km/h)and remained over the more central longitudes of the Atlantic.

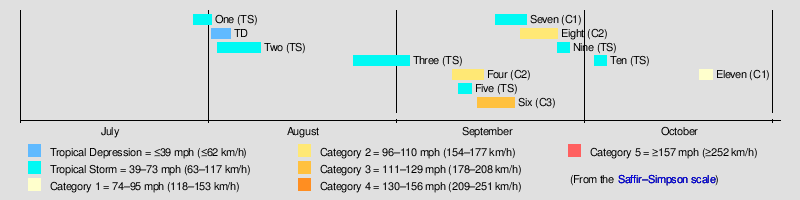

Timeline

Systems

Tropical Storm One

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | July 29 – August 1 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 70 mph (110 km/h) (1-min) 996 mbar (hPa) |

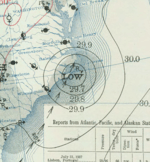

In late July, a stationary front was draped across the northeastern Gulf of Mexico. An area of rotation developed along this decaying boundary, developing into the season's first tropical depression around 00:00 UTC on July 29 while located about 225 miles (360 km) southwest of Tampa, Florida. The incipient cyclone moved steadily northeast and intensified into a tropical storm twelve hours later. It reached an initial peak of 65 mph (100 km/h) while in the Gulf of Mexico, making landfall at that intensity near Palm Harbor, Florida, at 22:00 UTC on July 29. The system initially weakened while crossing the state and emerging into the Atlantic, but surface observations along the North Carolina coastline supported peak winds around 70 mph (110 km/h) as the storm accelerated northeast; it is possible the cyclone possessed hurricane-force winds offshore. By 00:00 UTC on August 1, the system transitioned into an extratropical cyclone as an occluded front became attached to the circulation. It made landfall in Nova Scotia late on August 1 and curved northwest, dissipating over northern New Brunswick the next day.[3]

In Tampa, Florida, five-minute sustained winds reached 51 mph (82 km/h),[4] blowing down trees, utility poles, and electric wires.[5] Clearwater, Florida documented 8.88 in (226 mm) of rainfall in a 24-hour period, the heaviest rains measured in connection with the passing tropical storm. Some roads were washed out in Clearwater and minor losses of fruit were documented in surrounding Pinellas County. Farther north, gusts at Hatteras, North Carolina peaked at 65 mph (105 km/h).[4] Telephone and power service was disrupted in Halifax, Nova Scotia as the storm's remnants produced 35-mph (55 km/h) winds in the city. Three boats moored there were destroyed.[6]

Tropical Storm Two

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | August 2 – August 9 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 65 mph (100 km/h) (1-min) 1005 mbar (hPa) |

On August 1, a weak trough was identified north of the Greater Antilles. It developed into a tropical depression by 18:00 UTC on August 2 while positioned just southwest of Long Island, Bahamas; further intensification into a tropical storm occurred over Current Island 24 hours later. The system curved around the western periphery of an area of high pressure, attaining peak winds of 65 mph (100 km/h) based on data from ships that intersected the cyclone. Unlike the previous cyclone, this tropical storm never transitioned into an extratropical cyclone, instead weakening to a tropical depression around 00:00 UTC on August 9 and dissipating east of Nova Scotia twelve hours later.[3]

Tropical Storm Three

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | August 24 – September 2 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 70 mph (110 km/h) (1-min) 995 mbar (hPa) |

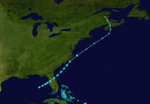

A tropical depression was first noted about 50 miles (85 km) east of Barbuda around 12:00 UTC on August 24, though it may have formed earlier beyond the coverage of available weather observations. It intensified into a tropical storm twelve hours but remained weak for several days after as it weaved through the Bahamas. The storm began to strengthen on August 28, a trend that continued over the next 48 hours. It struck the coastline near Daytona Beach, Florida, around 14:00 UTC on August 30 with winds of 70 mph (110 km/h). However, based on damage reports, it is feasible the cyclone was of hurricane intensity. The tropical storm moved northwest across the Southeastern United States, weakening to a tropical depression over southern Alabama early on September 1. It degenerated into a trough over northern Arkansas by 18:00 UTC the next day.[3]

The tropical storm caused widespread damage to electric and telecommunication wires in Florida, along the coast and as far as 100 mi (160 km) inland in Lake City. Gusts of 50–60 mph (80–95 km/h) impacted the coast between New Smyrna and St. Augustine.[7] At Savannah Beach, Georgia, the bulkhead and boardwalks were damaged by strong winds.[8] Flooding rains from the system washed out roads and bridges in the state's northwestern counties.[7] One squall associated with the tropical cyclone sank the SS Tarpon 40 mi (65 km) off Pensacola, drowning 18 of the 31 persons on board.[7][9][10] Vessels and planes were dispatcher by the United States Coast Guard to search for and rescue survivors.[10] Survivors remained at sea for up to 30 hours before being rescued.[11] Rainfall totals of at least 3 in (75 mm) spread as far west as eastern Mississippi, with a maximum rainfall of 13.8 in (350 mm) observed in Vernon, Florida.[12]:174 Heavy rains in southeastern Alabama caused the Pea and Choctawhatchee rivers to flood, inflicting roughly $62,500 in damage to adjacent property and crops.[13]

Hurricane Four

| Category 2 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | September 9 – September 14 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 100 mph (155 km/h) (1-min) 992 mbar (hPa) |

A strong tropical wave, originating near Cabo Verde around September 4, developed into a tropical storm by 00:00 UTC on September 9 while positioned about 480 miles (770 km) east-northeast of Barbuda. It intensified into the season's first hurricane within 24 hours, further maturing to Category 2 intensity with winds of 100 mph (160 km/h) by 06:00 UTC on September 12. The small hurricane moved steadily northwest throughout its lifespan, passing east of Bermuda before weakening to a tropical storm late the next day. It acquired well-defined frontal boundaries by 06:00 UTC on September 14, marking the system's transition into an extratropical cyclone. It made landfall in Nova Scotia and either elongated into a trough or merged with a frontal system over far eastern Canada twelve hours later.[3]

In Nova Scotia, 600,000 barrels of apples were lost in Annapolis Valley, totaling $1.5 million in damage to that crop. Homes, barns, and other buildings suffered structural damage. Wharves and a large boat were severely damaged in Shelburne, and a schooner that ran ashore in Lockeport suffered heavy damage as well. In New Brunswick, additional homes and barns were damaged.[14]

Tropical Storm Five

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | September 10 – September 11 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 70 mph (110 km/h) (1-min) 988 mbar (hPa) |

As part of the Atlantic hurricane reanalysis project, a previously unidentified tropical cyclone was discovered in 2012. Similar to the evolution of the season's first tropical cyclone, an area of low pressure formed along a dissipating frontal boundary early on September 10. It developed into a tropical storm by 06:00 UTC that day while located roughly 75 miles (120 km) south-southwest of Bermuda. The storm moved northwest over the next day, making a close approach to the Northeastern United States before veering to the northeast. It reached peak winds of 70 mph (110 km/h) around 18:00 UTC on September 11, when the structure of the system more resembled a subtropical cyclone than a strictly tropical one. It transitioned into an extratropical cyclone six hours later, striking Nova Scotia before becoming absorbed into the larger circulation of a non-tropical entity around 06:00 UTC on September 12.[3]

Hurricane Six

| Category 3 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | September 13 – September 19 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 125 mph (205 km/h) (1-min) 951 mbar (hPa) |

A tropical storm was first identified about 355 miles (570 km) east of Barbuda around 06:00 UTC on September 13, although it may have existed previously. The system executed a gradual curve toward the north while intensifying, becoming a hurricane early on September 14. It reached its peak intensity as a Category 3 hurricane with winds of 125 mph (205 km/h) by 06:00 UTC the next morning. It temporarily veered east but then resumed a northward motion, remaining a potent hurricane for several days. Extratropical transition occurred by 18:00 UTC on September 19 when an occluded front became attached to the storm. It turned northeast and ultimately opened up into a sharp trough over the far northern Atlantic late on September 20.[3]

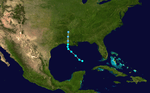

Tropical Storm Seven

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | September 16 – September 21 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 60 mph (95 km/h) (1-min) 1002 mbar (hPa) |

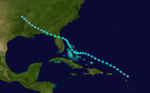

A tropical storm formed over the Bay of Campeche by 12:00 UTC on September 16, embarking on a steady northeastward course. Ship reports indicate that the cyclone reached peak winds of 60 mph (95 km/h) on September 18, but that it weakened to 45 mph (75 km/h) while making landfall near Port Eads, Louisiana, at 18:00 UTC the next day. The system turned toward the east thereafter, making a second landfall near Apalachicola, Florida, with winds of 40 mph (65 km/h) at 16:00 UTC on September 20. It briefly emerged into the far northeastern Gulf of Mexico before striking the Big Bend region of Florida as a tropical depression. The depression dissipated near Jacksonville, Florida, around 18:00 UTC on September 21.[3]

Damage in Florida was generally minor since winds on land were limited to around 30 mph (50 km/h). Some small boats in St. Marks broke from their moorings and sustained slight damage. A portion of Highway 6 between Wewahitchka and White City.[15] Two people drowned after their canoe capsized in rough seas generated by the storm near Everglades City.[16]

Hurricane Eight

| Category 2 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | September 20 – September 26 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 100 mph (155 km/h) (1-min) 982 mbar (hPa) |

A tropical wave likely emerged from the western coast of Africa around September 14. It developed into a tropical cyclone at some point of the next few days, with a specific date unclear in the absence of surface observations. At 06:00 UTC on September 20, a hurricane was conclusively identified about halfway between Cabo Verde and the Leeward Islands. It gained strength on a general northwest heading, intensifying into a Category 2 hurricane and attaining peak winds of 100 mph (160 km/h) from September 24–25. Slight weakening occurred as the system passed well north of Bermuda. It transitioned into an extratropical cyclone by 06:00 UTC on September 26 and struck Nova Scotia before turning northeast across Newfoundland and into the northern Atlantic. The extratropical cyclone was last noted over Iceland at 12:00 UTC on September 28, after which time it likely merged with another non-tropical low.[3]

The extratropical cyclone heavily impacted Nova Scotia, where vessels were pushed ashore, fishing gear was damaged, and trees were uprooted. In Liverpool, a boat launch and accompanying racing ships and other boats were destroyed. Three breakwaters were heavily damaged on Devils Island, in Brookland, and in Yarmouth, the second costing $80,000 to replace. A fourth breakwater at Western Head was washed away. One marine dredge was destroyed at Cape Negro and another was sunk somewhere between Lunenburg and Shelburne. Three scows en route to New Brunswick were also capsized in that area. In Port Bickerton, fishing stages, wharves, lobster traps, and nets were destroyed. A fish factory was also demolished in Halifax.[17]

Tropical Storm Nine

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

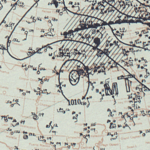

| Duration | September 26 – September 28 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 45 mph (75 km/h) (1-min) 1010 mbar (hPa) |

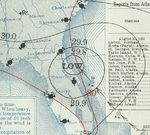

At 06:00 UTC on September 26, a tropical depression formed just north of Cuba. It intensified into a tropical storm by 18:00 UTC the following day based on reports from two ships. After attaining peak winds of 45 mph (75 km/h), the cyclone quickly transitioned to an extratropical cyclone by 12:00 UTC on September 28 as multiple fronts became intertwined with the circulation. The extratropical cyclone continued to parallel the U.S. East Coast, eventually making landfall in Newfoundland early on September 30. It strengthened into a hurricane-force low on October 1 but ultimately dissipated two days later as it merged with another cyclone and became increasingly elongated.[3]

Tropical Storm Ten

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | October 2 – October 4 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 45 mph (75 km/h) (1-min) 1002 mbar (hPa) |

In late September, a tropical wave moved westward across the Caribbean. An initial area of low pressure formed over the northwestern portion of the region on September 29, but this feature dissipated within two days. A new low formed and organized into a tropical storm around 00:00 UTC on October 2 while positioned about 425 miles (685 km) south of Mobile, Alabama. It reached peak winds of 45 mph (75 km/h) after six hours, with steady weakening thereafter as the storm moved west-northwest and then north. The system made two landfalls in central Louisiana near the Atchafalaya Basin between 12:00–14:00 UTC on October 3, both with winds of 40 mph (65 km/h). The system continued to degrade once inland, dissipating after 06:00 UTC on October 4 over southeastern Arkansas.[3]

The tropical storm caused the wettest 48-hour period in New Orleans's history, with 16.65 in (423 mm) of rainfall recorded as the storm made landfall; the maximum 24-hour rainfall total of 13.59 in (0.345 m) nearly broke the city's record for maximum daily rainfall.[18] City streets were submerged under as much as 3 ft (1 m) of water.[19] Blue laws were suspended for half a day to allow grocery store food supplies to reach stranded areas.[18] Damage was estimated at several thousands of dollars and the flooding was considered the city's most severe since the Great Mississippi Flood of 1927.[20] Crops around the city sustained considerable damage.[21] At Belle Chasse, Louisiana, the 15.40 in (391 mm) of rain recorded in 24 hours set the state record for the highest 24-hour rainfall in October.[22] The strongest recorded winds from the tropical cyclone occurred at Port Eads, Louisiana, where a 33-mph (53 km/h) wind gust was documented as the system was developing on October 2.[23]

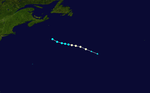

Hurricane Eleven

| Category 1 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | October 19 – October 21 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 80 mph (130 km/h) (1-min) 995 mbar (hPa) |

Similar to Tropical Storm Five, a new tropical cyclone that was not recognized in real time was found to have existed over the northern Atlantic. From October 16–17, a cold front moved eastward across the basin. An area of low pressure formed along the southern end of the dissipating boundary, initially harboring characteristics of an extratropical cyclone. This low became more symmetric while also intensifying, transitioning into a hurricane by 00:00 UTC on October 19 while located roughly 715 miles (1,150 km) southeast of Newfoundland. The system attained peak winds of 80 mph (130 km/h) within six hours and weakened shortly thereafter while moving west-northwest. It fell to tropical storm intensity by early on October 20; by 00:00 UTC the next day, there were no further indications of the storm. It either dissipated or was absorbed by a front encroaching from the west.[3]

Other storms

In addition to the eleven known tropical cyclones of at least tropical storm strength, the Atlantic hurricane reanalysis project also identified five tropical depressions. However, their marginal intensities precluded their addition to the official Atlantic hurricane track database (HURDAT). The first of these lasted from August 1–4 over the central Atlantic without affecting land, ultimately degenerating into a tropical wave. A second tropical depression developed in the Gulf of Mexico and passed near New Orleans, Louisiana, on August 29. A nearly stationary tropical depression developed in the southwestern Caribbean Sea on September 29 and dissipated two days later; it may have been absorbed by Tropical Storm Ten. This system was originally included in HURDAT as a tropical storm, but was found to have winds of only 30 mph (45 km/h) by the reanalysis. On October 8, a northward-moving tropical depression spawned from a tropical wave well east of the Lesser Antilles, eventually transitioning into an extratropical system on October 14. The season's final tropical cyclone was a nearly stationary tropical depression that persisted in the central Caribbean Sea between October 25–29. The reanalysis project also examined eleven other disturbances from 1937 for possible tropical or subtropical cyclone characteristics, including a low-pressure system that split from a front over the open Atlantic on January 1.[3]

Season effects

The table below includes the duration, names, landfall(s), denoted in parentheses, damage, and death totals of all tropical cyclones in the 1937 Atlantic hurricane season. The damage and deaths associated with a tropical cyclone include both its effects as a tropical cyclone as well as its progenitor and remnants.

| Saffir–Simpson scale | ||||||

| TD | TS | C1 | C2 | C3 | C4 | C5 |

| Storm name |

Dates active | Storm category

at peak intensity |

Max 1-min wind mph (km/h) |

Min. press. (mbar) |

Areas affected | Damage (USD) |

Deaths | Refs | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| One | July 29–August 1 | Tropical storm | 70 (110) | 996 | Florida, North Carolina, Nova Scotia | Unknown | None | [4] | ||

| Two | August 2–9 | Tropical storm | 65 (100) | 1005 | the Bahamas | None | None | [3] | ||

| Three | August 24–September 2 | Tropical storm | 70 (110) | 995 | Southeast United States | $62,500 | 18 | [13] | ||

| Four | September 9–14 | Category 2 hurricane | 100 (160) | 992 | Nova Scotia, eastern Canada | $1.5 million | None | [14] | ||

| Five | September 10–11 | Tropical storm | 70 (110) | 988 | Nova Scotia | None | None | [3] | ||

| Six | September 13–19 | Category 3 hurricane | 125 (205) | 951 | None | None | None | [3] | ||

| Seven | September 16–21 | Tropical storm | 60 (95) | 1002 | Florida | Unknown | 2 | [15] | ||

| Eight | September 20–26 | Category 2 hurricane | 100 (160) | 982 | Nova Scotia, Newfoundland | None | None | [17] | ||

| Nine | September 26–28 | Tropical storm | 45 (75) | 1010 | None | None | None | [3] | ||

| Ten | October 2–4 | Tropical storm | 45 (75) | 1002 | Louisiana | Unknown | None | [20][18] | ||

| Eleven | October 19–21 | Category 1 hurricane | 80 (130) | 995 | None | None | None | [3] | ||

| Season aggregates | ||||||||||

| 11 systems | July 29–October 21 | 125 (205) | 951 | $1.56 million | 20 | |||||

References

- "Florida Storm Service Begins on Wednesday". Miami Daily News. 42 (185). Miami, Florida. Associated Press. June 14, 1934. p. 5. Retrieved March 25, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Storm Warning Hook-Up Starts". The Austin Statesman. 65 (315). Austin, Texas. United Press. June 15, 1934. p. 7. Retrieved March 25, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- Christopher W. Landsea; et al. "Documentation of Atlantic Tropical Cyclones Changes in HURDAT". Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory. Retrieved May 9, 2019.

- Hurd, Willis E. (July 1937). "Small Tropical Disturbance of Late July, 1937" (PDF). Monthly Weather Review. Boston, Massachusetts: American Meteorological Society. 65 (7): 281–282. Bibcode:1937MWRv...65R.281H. doi:10.1175/1520-0493(1937)65<281b:STDOLJ>2.0.CO;2. Retrieved July 22, 2019.

- "Sunshine Routs 47-Mile an Hour Gulf Wind Storm". Tampa Morning Tribune (211). Tampa, Florida. July 30, 1937. p. 1. Retrieved July 22, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- "1937-1". Environment and Climate Change Canada. Ottawa, Quebec, Canada: Government of Canada. November 18, 2009. Retrieved July 22, 2019.

- Bennett, W. J. (August 1937). "Florida Section" (PDF). Climatological Data. Asheville, North Carolina: National Centers for Environmental Information. 41 (8): 6. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 22, 2019. Retrieved July 22, 2019.

- "Storm Blows Self Out on Upper Coast". Fort Myers News-Press. 53 (286). Fort Myers, Florida. Associated Press. August 31, 1937. p. 1. Retrieved July 22, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- "SS Tarpon". National Park Service. September 28, 2017. Retrieved July 22, 2019.

- "Steamer Sinks in Gulf of Mexico Squall; 25 of Crew Reported Lost". Petaluma Argus-Courier. 10 (36). Petaluma, California. United Press. September 1, 1937. p. 1. Retrieved April 22, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- Sibley, Celestine (September 4, 1937). "Tarpon Survivors Tell Battle to Live in Shark Infested Waters". The Pensacola Journal. 43 (118). Pensacola, Florida. p. 5. Retrieved April 22, 2020.

- Schoner, R. W.; Molansky, S. (July 1956). Rainfall Associated with Hurricanes (and Other Tropical Disturbances) (PDF) (Report). Washington, D.C: National Hurricane Research Project. Retrieved July 22, 2019.

- Emigh, E. D. (September 1937). "Alabama Section" (PDF). Climatological Data. Asheville, North Carolina: National Centers for Environmental Information. 43 (9): 1. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 22, 2019. Retrieved July 22, 2019.

- "1937-4". Government of Canada. Archived from the original on June 23, 2017. Retrieved March 15, 2020.

- "Storm Dissipates in North Florida". Miami Daily News. 284 (42). Miami, Florida. United Press. September 21, 1937. p. 1. Retrieved July 22, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Storm Brings Death to Seminole Women". Miami Daily News. Miami, Florida. September 21, 1937. p. 26. Retrieved July 22, 2019.

- "1937-7". Government of Canada. Archived from the original on June 23, 2017. Retrieved March 15, 2020.

- "Record Rains at New Orleans". Orlando Morning Sentinel (627). Orlando, Florida. October 4, 1937. p. 1. Retrieved May 10, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Storm Brings Floods to New Orleans and Halts Football Game". The Tampa Daily Times (204). Tampa, Florida. Associated Press. October 2, 1937. p. 1. Retrieved May 10, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- "City New Orleans Flooded by Rains". The Kingsport Times (236). Kingsport, Tennessee. October 3, 1937. p. 1. Retrieved May 10, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- United States Army Corps of Engineers (August 1972). History of Hurricane Occurrences Along Coastal Louisiana (PDF) (Report). Baton Rouge, Louisiana: Louisiana State University. p. 28. Retrieved May 10, 2018.

- "Louisiana". Climatological Data (PDF) (Report). 69. Asheville, North Carolina: National Climatic Data Center. October 1964. p. 122. Archived from the original (PDF) on May 10, 2019. Retrieved May 10, 2019.

- McDonald, W.F. (1937). "Louisiana Section". Climatological Data (PDF) (Report) (42 ed.). Asheville, North Carolina: National Climatic Data Center. p. 37. Archived from the original (PDF) on May 10, 2019. Retrieved May 10, 2019.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to 1937 Atlantic hurricane season. |