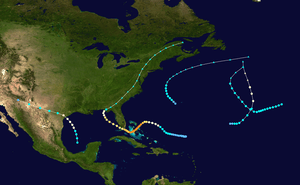

1929 Atlantic hurricane season

The 1929 Atlantic hurricane season was among the least active hurricane seasons in the Atlantic on record – featuring only five tropical cyclones. Of these five tropical systems, three of them intensified into a hurricane, with one strengthening further into a major hurricane (Category 3 or higher on the Saffir–Simpson hurricane wind scale).[1] The first tropical cyclone of the season developed in the Gulf of Mexico on June 27. Becoming a hurricane on June 28, the storm struck Texas, bringing strong winds to a large area. Three fatalities were reported, while damage was conservatively estimated at $675,000 (1929 USD).

| 1929 Atlantic hurricane season | |

|---|---|

Season summary map | |

| Seasonal boundaries | |

| First system formed | June 27, 1929 |

| Last system dissipated | October 22, 1929 |

| Strongest storm | |

| Name | "Bahamas" |

| • Maximum winds | 155 mph (250 km/h) (1-minute sustained) |

| • Lowest pressure | 924 mbar (hPa; 27.29 inHg) |

| Seasonal statistics | |

| Total depressions | 5 |

| Total storms | 5 |

| Hurricanes | 3 |

| Major hurricanes (Cat. 3+) | 1 |

| Total fatalities | 62 |

| Total damage | $9.985 million (1929 USD) |

| Related article | |

| |

The second storm, nicknamed the Bahamas hurricane, developed north of the Lesser Antilles. It was the most intense tropical cyclone of the season, peaking as a Category 4 hurricane on the Saffir–Simpson hurricane wind scale with maximum sustained winds of 155 mph (250 km/h) and a minimum barometric pressure of 924 mbar (27.3 inHg). The storm moved through the Bahamas at this intensity and later struck Florida while slightly weaker. Overall, this hurricane resulted in 59 deaths and at least $9.31 million in damage. The next three tropical cyclones did not impact land, with the last transitioning into an extratropical cyclone on October 22. Until HURDAT reanalysis in 2010, the final two systems were considered the same tropical cyclone.[2]

The season's activity was reflected with an accumulated cyclone energy (ACE) rating of 48.[1] ACE is, broadly speaking, a measure of the power of the hurricane multiplied by the length of time it existed, so storms that last a long time, as well as particularly strong hurricanes, have high ACEs. It is only calculated for full advisories on tropical systems at or exceeding 39 mph (63 km/h), which is tropical storm strength.[3]

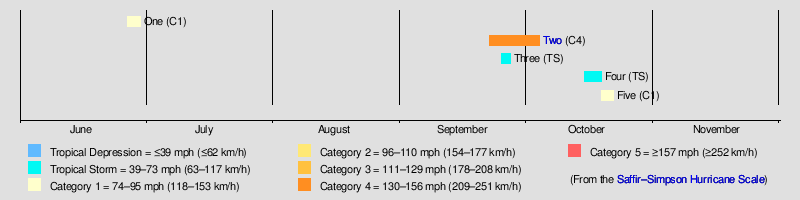

Timeline

Systems

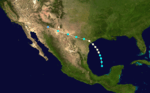

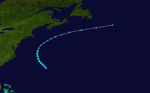

Hurricane One

| Category 1 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | June 27 – June 30 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 90 mph (150 km/h) (1-min) 982 mbar (hPa) |

After barometric pressures in the western Gulf of Mexico had been low for several days, the steamship Chester O. Swain encountered a disturbance of "probably moderate intensity" offshore Texas on June 28.[4] A tropical storm developed in the southwestern Gulf of Mexico on the previous day.[5] The storm was abnormally small, having a diameter of only about 20 mi (32 km).[4] It moderately intensified and by early on June 28, the storm became a hurricane. While offshore Texas, the hurricane peaked with winds of 90 mph (150 km/h). Shortly after making landfall near Matagorda Bay, a minimum barometric pressure of 982 mbar (29.0 inHg) was reported. The storm then accelerated westward across the Southwestern United States and weakened to a tropical storm early on June 29. However, it was still of "considerable intensity" while passing near El Paso about 24 hours later. Thus, the system was thought to have remained a tropical storm until early on June 30. Several hours later, the storm dissipated over Arizona.[5]

The storm brought hurricane-force winds to portions of Texas, including as far inland as Yorktown in DeWitt County. Additionally, a 60 to 80 mi (95 to 130 km) path observed gale force winds as far from the coast as Bexar, Kendall, Kerr, and Medina counties. Wind impacts were significant, with a "conservative" estimate of $310,000 in damage inflicted on crops, while buildings, windmills, power, telephone, and telegraph lines suffered about $365,000 in damage. There were three deaths in Wharton County, as well as several injuries. Outside of the area of wind damage, rainfall was considered "highly beneficial" to crops and range.[2]

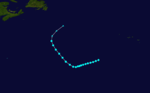

Hurricane Two

| Category 4 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | September 19 – October 1 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 155 mph (250 km/h) (1-min) 924 mbar (hPa) |

The Great Bahamas Hurricane of 1929

The second storm of the season originated from a tropical wave that developed in the vicinity of Cape Verde on September 11.[4] The wave became a tropical depression at 00:00 UTC on September 19, while located about 300 mi (480 km) north-northeast of Anegada in the British Virgin Islands. The depression drifted just north of due west while strengthening slowly, becoming a tropical storm early on September 22. Later that day, the storm curved northwestward. Around midday on September 23, it intensified into a hurricane. While turning southwestward on the following day, the hurricane began to undergo rapid deepening. Late on September 25, the system peaked with maximum sustained winds of 155 mph (250 km/h), an estimate based on pressure-wind relationship, with a minimum barometric pressure of 924 mbar (27.3 inHg).[5]

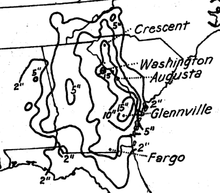

While crossing through the Bahamas, the storm struck Eleuthera and Andros, on September 25 and September 26, respectively. Late on September 27, the system weakened to a Category 3 hurricane and re-curved northwestward. At 13:00 UTC the next day, the hurricane made landfall near Tavernier, Florida. The storm then entered the Gulf of Mexico and continued weakening, falling to Category 2 intensity late on September 28. While approaching the Gulf Coast of the United States, the hurricane weakened to a Category 1 hurricane. Early on October 1, it made landfall near Panama City Beach, Florida. A few hours later, the hurricane weakened to a tropical storm and then became extratropical over southwestern Georgia shortly thereafter. The remnants continued northeastward up the East Coast of the United States, until entering Canada and dissipating over Quebec early on October 5.[5]

In the Bahamas, the hurricane brought strong winds and large waves to the archipelago. At Nassau, a weather station observed a wind gust of 164 mph (264 km/h).[6] Within the city alone, 456 houses were destroyed, while an additional 640 houses suffered damage. On Abaco Islands, 19 homes were demolished.[2] The hurricane damaged or destroyed 63 homes and buildings on Andros. Telegraph service was disrupted.[7] There were 48 deaths in the Bahamas.[2][4][7] Throughout the Bahamas and the Florida Keys, numerous boats and vessels were ruined or damaged. At the latter, strong winds were observed, with a gust up to 150 mph (240 km/h) in Key Largo.[2] However, damage there was limited to swamped fishing boats and temporary loss of electricity and communications.[4] Farther north, heavy rains flooded low-lying areas of Miami.[2] A devastating tornado in Fort Lauderdale damaged a four story hotel, a railway office building, and several cottages. In the Florida Panhandle, storm surge destroyed several wharves and damaged most of the oyster and fishing warehouses and canning plants.[4] Overall, there was approximately $2.36 million in damage and three deaths in Florida; eight others drowned offshore.[2]

Tropical Storm Three

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | September 25 – September 27 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 60 mph (95 km/h) (1-min) 1002 mbar (hPa) |

Historical weather maps indicate that a low pressure area was embedded within a west to east oriented stationary front over the northwestern Atlantic Ocean on September 24. The low quickly detached from the stationary front and acquired a closed circulation while tracking across sea surface temperatures of 80 °F (27 °C).[2] Early on September 25, a tropical depression formed just west of Bermuda and strengthened into a tropical storm later that day.[5] Around 02:00 UTC on September 26, a ship observed a barometric pressure of 1,002 mbar (29.6 inHg) – the lowest while the storm was tropical.[2] Four hours later, sustained winds peaked at 60 mph (95 km/h). The storm eventually curved northward, before becoming extratropical at 06:00 UTC on September 27, while located about 240 mi (390 km) south-southeast of Nantucket, Massachusetts. The extratropical remnants accelerated northeastward and then east-northeastward, before dissipating east-southeast of Newfoundland on September 29.[5]

Tropical Storm Four

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | October 15 – October 19 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 70 mph (110 km/h) (1-min) ≤999 mbar (hPa) |

Early on October 15, a low pressure area developed into a tropical storm, while located about 625 mi (1,005 km) southwest of Flores Island in the Azores.[5][2] The storm moved west-southwestward and slowly strengthened. At 12:00 UTC on October 17, the system peaked with maximum sustained winds of 70 mph (110 km/h) and a minimum barometric pressure of 999 mbar (29.5 inHg);[5] the latter was observed by a few ships.[2] Early on October 18, it curved northwestward and began to accelerate. Late the next day, the storm became extratropical, while located about 535 mi (860 km) south-southeast of Cape Race, Newfoundland. The extratropical remnants of the storm continued northeastward, until dissipating well southeast of Newfoundland on October 20.[5]

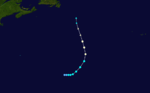

Hurricane Five

| Category 1 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | October 19 – October 22 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 80 mph (130 km/h) (1-min) ≤997 mbar (hPa) |

A trough extending southward from the previous system developed into a tropical depression at 12:00 UTC on October 19, while located about 890 mi (1,430 km) east-southeast of Bermuda.[5][2] Moving eastward, the depression intensified into a tropical storm early the next day. Later on October 20, it curved northeastward and accelerated. The storm intensified into a hurricane at 12:00 UTC on October 21. Strengthening further, the hurricane peaked with maximum sustained winds of 80 mph (130 km/h) and a minimum barometric pressure of 997 mbar (29.4 inHg). At 06:00 UTC on October 22, the hurricane became extratropical, while situated about 665 mi (1,070 km) south-southeast of Cape Race, Newfoundland. The remnants moved north-northwestward and dissipated early on October 23.[5]

Season Effects

References

- Atlantic basin Comparison of Original and Revised HURDAT. Hurricane Research Division; Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory (Report). Miami, Florida: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. February 2014. Retrieved July 4, 2014.

- Christopher W. Landsea; et al. (December 2012). Documentation of Atlantic Tropical Cyclones Changes in HURDAT. Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory (Report). Miami, Florida: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved June 29, 2014.

- David Levinson (August 20, 2008). 2005 Atlantic Ocean Tropical Cyclones. National Climatic Data Center (Report). Asheville, North Carolina: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved July 1, 2013.

- "The Tropical Storm Of June 28, 1929" (PDF). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. October 1929. p. 417. Retrieved May 28, 2012.

- "Atlantic hurricane best track (HURDAT version 2)" (Database). United States National Hurricane Center. May 25, 2020.

- "164-Mile Wind Blows on Mt. Washington". Science News. 165 (10). March 3, 1934. Archived from the original on October 15, 2007. Retrieved July 5, 2014.

- Pierce S. Rosenberg; et al. (August 1970). The Great Andros Hurricane Of September 25, 26, 27, 1929 (PDF). AUTEC Environmental Science Section (Report). Miami, Florida: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration; Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory; National Hurricane Center. Retrieved July 5, 2014.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to 1929 Atlantic hurricane season. |