1926 Nassau hurricane

The 1926 Nassau hurricane also known as the San Liborio hurricane or The Great Bahamas Hurricane of 1926, in Puerto Rico, was a destructive Category 4 hurricane that affected the Bahamas at peak intensity. Although it weakened considerably before its Florida landfall, it was one of the most severe storms to affect the Bahamian capital Nassau and the island of New Providence in several years until the 1928 Okeechobee hurricane, which occurred just two years later. The storm also delivered flooding rains and loss of crops to the southeastern United States and Florida.

| Category 4 major hurricane (SSHWS/NWS) | |

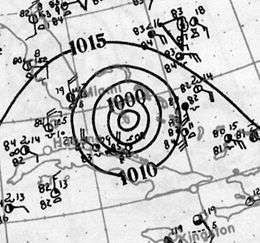

Surface weather analysis showing the hurricane over the Bahamas on July 26 | |

| Formed | July 22, 1926 |

|---|---|

| Dissipated | August 2, 1926 |

| (Extratropical after July 31) | |

| Highest winds | 1-minute sustained: 140 mph (220 km/h) |

| Lowest pressure | < 967 mbar (hPa); 28.56 inHg |

| Fatalities | 287 direct |

| Damage | $7.85 million (1926 USD) |

| Areas affected | Lesser Antilles, Puerto Rico, Hispaniola, the Bahamas, Florida, Southeastern United States |

| Part of the 1926 Atlantic hurricane season | |

Meteorological history

The system was first spotted east of the Lesser Antilles as a weak tropical storm on July 22. Moving northwest, the tropical storm passed near Dominica with winds of 70 miles per hour (113 km/h) before entering the eastern Caribbean.[1] It reached hurricane status at 06:00 UTC on July 23, and a short while later passed just south of Puerto Rico. The cyclone attained its first peak of 105 mph (169 km/h) before hitting Cabo Rojo early on July 24.[1] San Juan recorded maximum winds of around 66 mph (106 km/h) and a low barometric pressure of 1,005 millibars (29.68 inHg) as the eye of the hurricane passed near the extreme southwest corner of Puerto Rico.[2] The storm continued northwest and tracked just east of Hispaniola, losing some intensity to land interaction; by 18:00 UTC on July 24 its winds diminished to 85 mph (137 km/h).[1] However, the storm began rapid re-intensification as it moved over the Turks and Caicos Islands early on July 25.[1]

The storm continued strengthening, attaining the equivalence of major hurricane status by 12:00 UTC that day. By the time it reached the central Bahamas at 00:00 UTC on July 26, it reached winds of 140 mph (225 km/h).[1] After 12:00 UTC, while still moving northwest, the cyclone made landfall on New Providence and crossed over Nassau, where winds were unofficially estimated at 135 mph (217 km/h).[3] Reducing its forward speed, the storm weakened considerably after passing New Providence, losing major hurricane status by 06:00 UTC on July 27.[1] As the storm neared the Florida coast, it curved somewhat to the north-northwest and passed just east of Cape Canaveral early on July 28. It made landfall at 10:00 UTC near present-day Edgewater, near the Canaveral National Seashore just south of New Smyrna Beach, with winds of 105 mph (169 km/h).[1] Prior to reanalysis in 2010, the storm was estimated to have made landfall farther south, near Cocoa Beach.[4] In Florida, the storm's lowest known barometric pressure of 967 mb (28.6 inHg) was estimated,[5] although it was likely deeper near the Bahamas.

After landfall, the storm curved northwestward and weakened rapidly as it moved inland, weakening to a tropical storm southwest of Jacksonville.[1] On July 29, it moved across Georgia as a weakening tropical storm and entered Alabama as a tropical depression. It continued across the southeastern United States while losing tropical characteristics, gradually beginning to curve northeastward over Arkansas, Missouri, and the Ohio Valley, becoming extratropical by 00:00 UTC on August 1.[1] It finally dissipated the following day as it moved northeastward over Lake Ontario.

Impact

On its path, the storm killed more than 287 people in Puerto Rico, the Dominican Republic, Bahamas, and Florida.[6] In the Bahamas, the storm caused over 100 deaths, but the exact total varies from 106[7] to 146.[8] Combined with two later storms in September and October, the entire hurricane season killed more than 300 people in the Bahamas.[9]

Puerto Rico and Hispaniola

The storm initially caused little damage until it passed near Puerto Rico, where heavy crop damage, most notably to coffee plantations in the west-central region of the island, occurred.[2] Strong winds affected the entire island, and all rivers in the southern half of the island overflowed their banks.[10] Heavy rainfall of around 6.18 in (157 mm) occurred on the island, while the average rainfall reported for July was 6.5 in (165 mm). About 25 people drowned when heavy floods resulted from rapid rise of rivers.[2] Total losses in Puerto Rico were estimated at $2.350 million.[2] The storm is known as the San Liborio hurricane for its effects in Puerto Rico.[10] Estimated damage amounted to around $3 million in eastern Santo Domingo as the storm center passed over the eastern half of Hispaniola.[2]

The Bahamas

The cyclone caused significant damage over much of the central Bahamas. The storm destroyed 500 homes—90% of the total—on Great Exuma Island, "swept away" roads and bridges, and ruined unharvested agricultural produce, including the entire corn crop.[11] Dead livestock littered the landscape.[11] On Eleuthera, the storm downed coconuts and other fruit crops; strong winds and high tides leveled 240 dwellings, 14 churches, and two schools on the island.[12] On the island, the storm rendered most roads unusable and washed the primary causeways out to sea, leaving 2 to 4 feet (0.61 to 1.2 m) of water covering the island.[12] At least 74 drownings occurred on nearby Cat Island.[13] The storm also wrecked most of the homes on the Berry Islands.[14] On Bimini, the hurricane razed a lighthouse and a wireless station; strong winds tore roofs off several churches and other buildings. After the storm, the crew of the USS Bay Spring delivered over 1,000 tonnes (1,000,000 kg) of munitions and construction materials to aid the stricken residents.[15] Nearby settlements on Andros lost most or all of their buildings; in some areas the storm ruined the sisal crop, felled 95% of the coconut trees, destroyed stone buildings, and left water more than 5 ft (1.5 m) deep.[16] Although damage reports are not clear, the storm caused the most significant losses on New Providence, especially in Nassau, where "some roofs were torn off entirely" and the storm was "more fearful and devastating than any most people can remember", according to an eyewitness account posted in the July issue of the Monthly Weather Review.[3] Trees, power poles, and various debris littered streets, and many people were left homeless. Automobiles at Nassau were also reported damaged by the storm, and flooding was reported.[3]

Florida

Areas near the point of landfall reported significant damage to buildings, crops, and communications wires, especially New Smyrna Beach.[17] The storm disrupted telephone and electric service in Daytona Beach, while high tides destroyed beachfront businesses and sank watercraft.[18] Points farther south along the Florida coast, such as Miami, received only a brush from the storm, resulting in rains and some light wind damage, mainly to fruit crops. The Palm Beach area reported extensive coastal flooding that damaged coastal structures.[18] The storm was also reported to have caused damage around the point of landfall in Melbourne, where uprooted citrus trees and roofs blown off were reported. An observer on Merritt Island reported a heavy storm surge along the Indian River that damaged or destroyed homes, docks, and boats.[17] Substantial rainfall attended the storm in its passage over Florida, peaking at 10.08 in (256 mm) at Merritt Island.[17] Damage estimates in Florida exceeded $2.5 million.

Records

Prior to the record-breaking 2005 Atlantic hurricane season, this was the strongest hurricane ever recorded in July until Hurricane Dennis of 2005, a strong Category 4 hurricane with top sustained winds of 150 mph (241 km/h) and a pressure of 930 millibars (27.46 inHg),[19] surpassed the intensity of the July 1926 hurricane.

See also

- List of Atlantic hurricanes

- List of Florida hurricanes

References

- "Atlantic hurricane best track (HURDAT version 2)" (Database). United States National Hurricane Center. May 25, 2020.

- Charles L. Mitchell (1926). "Storms and Weather Warnings" (PDF). U.S. Weather Bureau. Retrieved 2007-08-05.

- Nassau Guardian (1926). "The Nassau Hurricane, July 25–26, 1926" (PDF). U.S. Weather Bureau. Retrieved 2007-08-05.

- Blake; Rappaport & Landsea (2006). "The Deadliest, Costliest, and Most Intense United States Tropical Cyclones (1851 to 2006)" (PDF). NOAA. Archived (PDF) from the original on 20 August 2007. Retrieved 2007-08-05.

- National Hurricane Center; Hurricane Research Division; Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory (May 2018). "Continental United States Hurricanes (Detailed Description)". AOML. Miami, Florida: United States National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's Office of Oceanic & Atmospheric Research. Retrieved August 14, 2020.

- Barnes 1998, p. 110

- National Hurricane Center; Hurricane Research Division; Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory (April 2012). "Atlantic hurricane best track (HURDAT) Meta Data, 1926–1930". United States National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's Office of Oceanic & Atmospheric Research. Retrieved 2012-09-01.

- "400 Persons Missing in the Bahama Storm". New York Times. August 3, 1926.

- Landsea, Christopher W.; Steve Feuer; Andrew Hagen; David A. Glenn; Jamese Sims; Ramón Pérez; Michael Chenoweth & Nicholas Anderson (February 2012). "A reanalysis of the 1921–1930 Atlantic hurricane database" (PDF). Journal of Climate. 25 (3): 865–85. Bibcode:2012JCli...25..865L. doi:10.1175/JCLI-D-11-00026.1. Retrieved 2015-04-05.

- José Colón (1970). Pérez, Orlando (ed.). "Notes on the Tropical Cyclones of Puerto Rico, 1508–1970" (Pre-printed). National Weather Service: 26. Retrieved August 31, 2012. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Neely 2009, p. 129

- Neely 2009, p. 148

- Neely 2009, p. 142

- Neely 2009, p. 134

- Neely 2009, p. 131

- Neely 2009, p. 122

- "Washington Forecast District" (PDF). Monthly Weather Review. 54 (7): 312–14. July 1926. Bibcode:1926MWRv...54..312.. doi:10.1175/1520-0493(1926)54<312:WFD>2.0.CO;2.

- "Nassau Is Wrecked by Tropical Storm". New York Times. Jacksonville, Florida. Associated Press. July 29, 1926.

- Beven, Jack. "Tropical Cyclone Report: Hurricane Dennis, 4–13 July 2005" (PDF). nhc.noaa.gov. Miami: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2015-04-06.

Bibliography

- Barnes, Jay (1998), Florida's Hurricane History, Chapel Hill, North Carolina: Chapel Hill Press, ISBN 978-0-8078-2443-6

- Neely, Wayne (2009), The Great Bahamian Hurricanes of 1926: the Story of Three of the Greatest Hurricanes to Ever Affect the Bahamas, New York: iUniverse, ISBN 978-1440151750