1925 Florida tropical storm

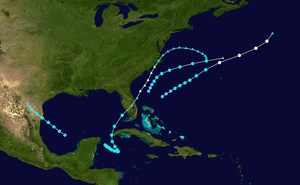

The 1925 Florida tropical storm was the deadliest tropical cyclone to impact the United States that did not become a hurricane.[1] The fourth and final storm of the season, it formed as a tropical depression on November 27 near the Yucatán Peninsula, the system initially tracked southeastward before turning north as it gradually intensified. After skirting western Cuba on November 30, the storm reached peak winds of 65 mph (105 km/h) before striking central Florida on December 1. Within hours, the system transitioned into an extratropical cyclone and emerged into the Atlantic Ocean. The system moved onshore once more on December 2 in North Carolina before turning east, away from the United States. On December 5, the system is presumed to have dissipated offshore.[2]

| Tropical storm (SSHWS/NWS) | |

Weather map of the storm after becoming an extratropical cyclone off the coast of the Eastern United States | |

| Formed | November 27, 1925 |

|---|---|

| Dissipated | December 1, 1925 |

| Highest winds | 1-minute sustained: 65 mph (100 km/h) |

| Lowest pressure | 995 mbar (hPa); 29.38 inHg |

| Fatalities | 73 direct |

| Damage | $3 million (1925 USD) |

| Areas affected | Eastern United States, Cuba and Honduras |

| Part of the 1925 Atlantic hurricane season | |

Throughout the system's existence, it was responsible for 73 fatalities, most of which resulted from offshore incidents. The worst loss of life took place off East Coast, where the 30 crewmen of the American SS Catopazi drowned. Property damage amounted to $3 million, $1 million of which was in Jacksonville.

Meteorological history

The 1925 Florida tropical storm was first identified on November 27, 1925 as a tropical depression situated to the southeast of the Yucatán Peninsula, nearly a month after the official end of the hurricane season.[3][4] Situated over 80 °F (27 °C) waters,[5] the system slowly intensified, attaining tropical storm status roughly 12 hours after forming, as it drifted towards the southeast before abruptly turning north-northwestward. Throughout November 30, the storm quickly strengthened as it brushed the western tip of Cuba with winds of 50 mph (85 km/h).[3] Once in the Gulf of Mexico, the storm turned northeastward and intensified to peak winds of 65 mph (105 km/h).[2] The lowest known barometric pressure attained by the storm was 995 mbar (hPa; 29.38 inHg) as it moved inland.[2] Within hours of reaching this strength, the storm made landfall just south of Fort Myers, Florida early on December 1 as it began to transition into an extratropical cyclone.[2][6] The storm was originally thought to have moved ashore as a minimal hurricane, thus becoming the latest-landfalling hurricane in United States history. However, a reanalysis in 2011 lowered the peak winds.[2] While crossing the Florida peninsula, the storm briefly weakened as it completed its transition; however, once back over water, it re-intensified.[2]

Off the coast of The Carolinas, the former tropical storm became a large and powerful extratropical cyclone, attaining peak winds of 90 mph (140 km/h) along with a pressure of 979 mbar (hPa; 28.91 inHg), measured by the USS Patoka.[3][6] Gale force winds extended to at least New Jersey, where winds of 70 mph (110 km/h) were recorded.[2] Throughout December 2, the storm gradually slowed as it tracked roughly parallel to the East Coast. Later that day, the system moved onshore again, this time between Wilmington and Cape Hatteras,[6] with winds equivalent to a minimal hurricane.[3] A strong area of high pressure located over the Canadian Maritimes caused the system to turn towards the east-southeast.[6] Over the following few days, the storm gradually weakened as it moved away from North Carolina. By December 5, the storm was no longer identifiable and is presumed to have dissipated offshore.[2] However, a monthly weather review published in 1925 that documented the system indicated that the cyclone continued towards the east, eventually impacting Bermuda and the Azores.[6] Later analysis in 2009 concluded that a separate extratropical low, which formed near the remnants of the storm, was responsible for inclement weather in both areas.[2]

Impact

From November 28 to November 30, the storm brought light rains to most of eastern Cuba.[5] Although the cyclone had tropical storm-force winds at the time, the highest recorded wind in Cuba was 12 mph (18 km/h) in Havana and only 0.22 in (5.58 mm) of rain fell in the city. The Swan Islands, off the northern coast of Honduras, recorded 2.36 in (59.94 mm) of precipitation during a three-day span.[5]

United States

During its passage through Florida, the storm produced torrential rain over coastal cities, peaking in Miami at 14.08 in (358 mm).[2] The storm caused significant property and crop damage along the Gulf Coast of Florida. Trees, power lines, and telegraph wires were knocked down by high winds along the Suwannee River.[6] Communication throughout southern Florida was severed as miles of telegraph wires were downed during the evening of November 30.[7] Structures previously considered safe from storms due to their location over 100 ft (30.4 m) inland sustained significant damage, probably from storm surge. Beaches along the Atlantic coast also sustained considerable damages from the storm.[6] Four people were killed near Tampa in two separate incidents . The first occurred when a house collapsed on three men, pinning them to the ground. The second incident occurred after a woman ran outside her home and was struck by a tree limb.[8] At least 12 workmen were killed and 38 others injured after the bunkhouse they were sleeping in collapsed due to high winds.[9] The facility in which they were working in also sustained $200,000 in damage from a fire ignited by the cyclone.[10] Throughout Florida, property loses were estimated at $3 million,[11] with $1 million in Jacksonville alone. Damages to the citrus industry were also significant, with total losses exceeding $600,000.[6] Losses in Miami amounted to $250,000 as up to 2 ft (0.61 m) inundated the city for more than two days.[12]

Shipping incidents resulting from the storm caused several deaths. A schooner carrying seven people sunk, killing all its occupants. A tug boat sank off the coast of Mobile, Alabama while towing a lumber barge; the fate of the crew is unknown. A ship named the American SS Catopazi sank between Charleston, South Carolina and the northern coast of Cuba, with all 30 crew members lost. Near Daytona Beach, a vessel carrying 2,000 cases of liquor sank along with all six crewmen. The last incident, involving a yacht, occurred off the coast of Georgia. The ship sank near Savannah, Georgia with the 12 crew members drowning. The total loss of life at sea was at least 55.[6] Shipping throughout the East Coast was crippled by the storm as vessels were forced to seek shelter at port.[13]

Due to the large size of the storm as an extratropical cyclone, gale and storm warnings in force from Beaufort, North Carolina to Eastport, Maine.[14] In North Carolina, heavy rains and strong winds were reported along the coast. Near record high water rises were recorded around Wilmington.[15] Cape Hatteras was temporarily isolated from the surrounding areas as the high winds from the storm knocked down power lines throughout the area. Several buildings along the coast and numerous boats sustained considerable damage.[16] As far north as New Jersey, gale-force winds produced by the powerful extratropical storm caused significant damage and killed at least two people.[2] Large swells and high winds throughout New Jersey, southern New York and Connecticut resulted in significant damage. Along the coast of Long Island, large waves resulted in severe beach erosion which threatened to undermine homes.[17] Parts of Coney Island were inundated by the increased surf, damaging homes and businesses. Several barges in nearby marinas were torn from their moorings and swept out to sea.[18] In Sandy Hook, several workmen were nearly killed after a building collapsed amidst high winds.[17] Minor precipitation was recorded throughout Rhode Island, peaking at 0.62 in (16 mm).[19]

See also

References

- Blake, Eric; Landsea, Christopher; Gibney, Ethan (August 2011). The Deadliest, Costliest, and Most Intense United States Tropical Cyclones from 1851 to 2010 (PDF). National Hurricane Center. p. 9. Retrieved 3 September 2015.

- Hurricane Research Division (2011). "Documentation of Atlantic Tropical Cyclones Changes in HURDAT". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved August 24, 2011.

- "Atlantic Best Tracks, 1851 to 2007 Reanalyzed". National Hurricane Center. 2009. Retrieved March 20, 2009.

- Neal Dorst (January 21, 2010). "When is hurricane season ?". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Archived from the original on 24 April 2011. Retrieved March 11, 2011.

- "Raw Observations for Hurricane Four 1925" (XLS). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. 2009. Retrieved March 21, 2009.

- W. P. Day (1926). "Monthly Weather Review for 1925" (PDF). National Weather Service. Archived (PDF) from the original on 25 February 2009. Retrieved March 8, 2009.

- United Press (December 2, 1925). "Florida Back To Business as Effects of Storm Pass". The Pittsburgh Press. p. 17. Retrieved January 2, 2011.

- Staff Writer (December 2, 1925). "Four Lives Lost in Storm Off Tampa Coast". Morning Avalanche.

- Associated Press (December 1, 1925). "Florida Storm Kills Workmen". Youngstown Vindicator. p. 1. Retrieved January 2, 2011.

- Associated Press (December 1, 1925). "5 Dead, 4 Missing Is Toll Of Storm That Hits Florida". Ellensburg Daily Record. p. 1. Retrieved January 2, 2011.

- Associated Press (December 2, 1925). "Storm Still Rages In South". Kentucky New Era. p. 1. Retrieved January 2, 2011.

- United Press (December 2, 1925). "Florida Swept By Heavy Gale". Times Daily. p. 1. Retrieved January 2, 2011.

- United Press (December 4, 1925). "Storm Rages Along Northeast Seaboard". Berkeley Daily Gazette. p. 11. Retrieved January 2, 2011.

- Associated Press (December 3, 1925). "Storm Moves Northward". Herald-Journal. p. 3. Retrieved January 2, 2011.

- Associated Press (December 2, 1925). "Tropical Storm Ravages Florida Coast". The Morning News Review.

- Staff Writer (December 2, 1925). "Middle Atlantic Coast is Swept by Furious Gale". The Zanesville Signal.

- Associated Press (December 4, 1925). "Storm Hits New York". Herald-Journal. p. 2. Retrieved January 2, 2011.

- Associated Press (December 3, 1925). "Storm Lashes Eastern Coast". The Milwaukee Journal. p. 35.

- Staff Writer (December 3, 1925). "Rain Storm Not So Severe". The Sunday Tribune. p. 1. Retrieved January 2, 2011.