1913 Atlantic hurricane season

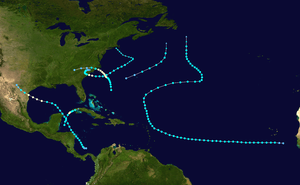

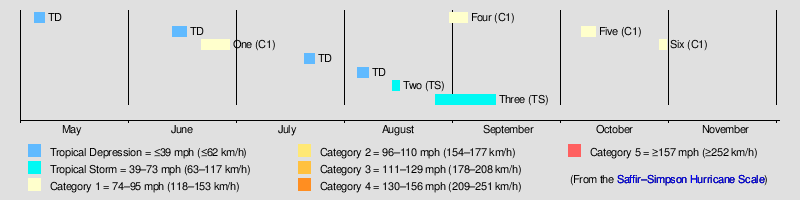

The 1913 Atlantic hurricane season was the third consecutive year with a tropical cyclone developing before June. Although no "hurricane season" was defined at the time, the present-day delineation of such is June 1 to November 30.[1] The first system, a tropical depression, developed on May 5 while the last transitioned into an extratropical cyclone on October 30. Of note, the seventh and eighth cyclones existed simultaneously from August 30 to September 4.

| 1913 Atlantic hurricane season | |

|---|---|

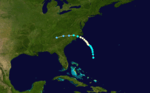

Season summary map | |

| Seasonal boundaries | |

| First system formed | May 5, 1913 |

| Last system dissipated | October 30, 1913 |

| Strongest storm | |

| Name | Four |

| • Maximum winds | 85 mph (140 km/h) (1-minute sustained) |

| • Lowest pressure | 976 mbar (hPa; 28.82 inHg) |

| Seasonal statistics | |

| Total depressions | 10 |

| Total storms | 6 |

| Hurricanes | 4 |

| Total fatalities | 6 |

| Total damage | At least $4 million (1913 USD) |

| Related article | |

| |

Of the season's ten tropical cyclones, six became tropical storms and four strengthened into hurricanes. Furthermore, none of these strengthened into a major hurricane—Category 3 or higher on the modern-day Saffir–Simpson hurricane wind scale—marking the sixth such occurrence since 1900.[2] The strongest hurricane of the season peaked as only a Category 1 with winds of 85 mph (140 km/h). That system left five deaths and at least $4 million in damage in North Carolina. The first hurricane of the season also caused one fatality in Texas, while damage in South Carolina from the fifth hurricane reached at least $75,000.

The season's activity was reflected with an accumulated cyclone energy (ACE) rating of 36.[2] ACE is, broadly speaking, a measure of the power of the hurricane multiplied by the length of time it existed, so storms that last a long time, as well as particularly strong hurricanes, have high ACEs. It is only calculated for full advisories on tropical systems at or exceeding 39 mph (63 km/h), which is tropical storm strength.[3]

Timeline

Systems

Hurricane One

| Category 1 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | June 21 – June 29 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 75 mph (120 km/h) (1-min) 988 mbar (hPa) |

Weather maps and ship data indicate the development of a tropical depression in the southwestern Caribbean Sea around 06:00 UTC on June 21.[4] Moving north-northwestward, the depression accelerated and intensified into a tropical storm on the following day. Early on June 23, the storm made landfall near the Honduras–Nicaragua border with winds of 40 mph (65 km/h). Thereafter, it continued north-northwestward and oscillated slightly in strength. The system made another landfall near Cancún, Quintana Roo, with winds of 45 mph (75 km/h) late on June 25. After briefly crossing the Yucatan Peninsula, the cyclone emerged into the Gulf of Mexico and eventually began moving more to the west-northwest. Early on June 27, it deepened into a Category 1 hurricane and peaked with maximum sustained winds of 75 mph (120 km/h). The hurricane then curved northwestward and made landfall in Padre Island, Texas, at the same intensity around 01:00 UTC on June 28. After moving inland, the storm quickly weakened and dissipated over Val Verde County just under 24 hours later.[5]

Impact in Central America and Mexico is unknown. The storm brought heavy rainfall to portions of South Texas. At Montell, 20.6 in (520 mm) of precipitation fell in about 19 hours, while Uvalde observed 8.5 in (220 mm) of rain in approximately 17 hours. The resultant flooding caused considerable damage to lowlands, houses, and stock. Additionally, communication by telegraph and telephone were cut-off for several days and traffic was interrupted due to inundated streets. One person drowned in Montell. Strong winds were also reported, with winds of 100 mph (160 km/h) over Central Padre Island. Along the coast, storm surge peaked at 12.7 ft (3.9 m) in Galveston.[4]

Tropical Storm Two

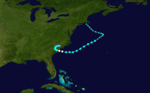

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | August 14 – August 16 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 45 mph (75 km/h) (1-min) <1008 mbar (hPa) |

A low pressure area detached from a stationary front and developed into a tropical depression on August 14 while located about 185 mi (300 km) west-southwest of Bermuda.[4][5] The depression moved rapidly northeastward and intensified into a tropical storm on August 15. Thereafter, it peaked with maximum sustained winds of 45 mph (75 km/h).[5] By August 16, the storm transitioned into an extratropical cyclone while situated about 290 mi (470 km) southeast of Sable Island, Nova Scotia.[4][5] The remnants were promptly absorbed by a frontal boundary.[4]

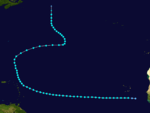

Tropical Storm Three

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | August 26 – September 12 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 70 mph (110 km/h) (1-min) <995 mbar (hPa) |

Weather maps and ship data indicated a tropical depression formed near the west coast of Africa on August 26.[4] Early the next day, the system strengthened into a tropical storm. It then tracked westward for several days, threatening the Lesser Antilles before turning north-northwestward on September 3. Eventually, the storm recurved to the northeast before beginning an eastward direction on September 7. The following morning, it peaked with maximum sustained winds of 70 mph (110 km/h) – just shy of hurricane status. Thereafter, the cyclone moved northward to northwestward for the next few days. Around 12:00 UTC on September 12, the storm became extratropical while located about 290 mi (470 km) southeast of Cape Race, Newfoundland and Labrador.[5]

Hurricane Four

| Category 1 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | August 30 – September 4 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 85 mph (140 km/h) (1-min) 976 mbar (hPa) |

A tropical storm developed about halfway between Bermuda and the Bahamas at 12:00 UTC on August 30. The storm moved slowly north-northwestward and approached the East Coast of the United States. By September 1, it intensified into a Category 1 hurricane. Eventually, the hurricane curved to the northwest. While located offshore North Carolina early on September 3, the cyclone peaked with maximum sustained winds of 85 mph (140 km/h) and a minimum barometric pressure of 976 mbar (28.8 inHg), making it the strongest tropical cyclone of the season. Hours later, it made landfall near Cape Lookout at the same intensity. Shortly after moving inland, the system weakened to a tropical storm. By September 4, it deteriorated to a tropical depression before dissipating over northeastern Georgia.[5]

In North Carolina, winds as high as 74 mph (119 km/h) at Hatteras caused severe crop losses, especially in areas adjacent to Pamlico Sound. The worst of the property damage occurred in the vicinity of New Bern and Washington. At the latter, northeast to southeast gales caused waterways to rise 10 ft (3.0 m) above previous high-water marks. Large railroad bridges in both New Bern and Washington were washed away, as were many other small bridges. Many low-lying streets were inundated.[4] The storm was considered "the worst in history" at Goldsboro.[6] In Farmville, a warehouse collapsed, killing two people inside while three deaths occurred elsewhere in the state.[7] Throughout North Carolina, numerous telegraph and telephone lines were damaged. Similarly, telegraph and telephone lined were downed in rural areas of Virginia. Small houses in Newport News, Ocean View, and Old Point were unroofed. Overall, this storm caused five fatalities and $4–5 million in damage.[4]

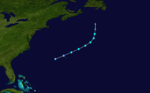

Hurricane Five

| Category 1 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | October 6 – October 10 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 75 mph (120 km/h) (1-min) 989 mbar (hPa) |

An extratropical cyclone developed offshore Rhode Island on October 2 and moved southeastward. Eventually, the system curved southwestward and transitioned into a tropical storm on October 6 while situated about 325 mi (525 km) northwest of Bermuda.[4][5] After becoming tropical, the storm continued to move southwestward and approached the Southeastern United States. By October 7, it curved westward and began to intensify. The storm became a Category 1 hurricane around 06:00 UTC on October 8. Peaking with maximum sustained winds of 75 mph (120 km/h) and a minimum barometric pressure of 989 mbar (29.2 inHg), the hurricane made landfall near McClellanville, South Carolina, about eight hours later. By the evening of October 8, the cyclone weakened to a tropical storm and fell to tropical depression intensity by late on October 9. Early the following day, it became extratropical and was soon absorbed by a strong cold front over North Carolina.[5]

Although the storm had been a hurricane at landfall, the highest recorded winds in South Carolina were 37 mph (60 km/h). The Georgetown Railway and Light Company and the Home Telephone Company suffered the worst damage. Throughout Georgetown, wires and poles were toppled, which briefly cut-off communications. Fences and trees limbs were also blown down.[4] Heavy rain, peaking at 4.88 in (123.95 mm), was recorded along the coast of South Carolina.[7] Precipitation led to minor crop damage, totaling approximately $75,000.[4]

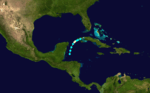

Hurricane Six

| Category 1 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | October 28 – October 30 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 75 mph (120 km/h) (1-min) <992 mbar (hPa) |

The final tropical storm developed in the northwestern Caribbean Sea about 60 mi (97 km) southeast of Banco Chinchorro, Mexico, at 00:00 UTC on October 28. Moving north-northeast, the storm reached Category 1 hurricane intensity about 24 hours after its classification. Around that time, it peaked with maximum sustained winds of 75 mph (120 km/h). Around 06:00 UTC on October 29, the system made landfall near Cape San Antonio, Cuba, at the same intensity. After about six hours over Cuba, the hurricane weakened to a tropical storm.[5] It transitioned into an extratropical cyclone in present-day Mayabeque Province before being absorbed by a frontal boundary shortly thereafter.[4][5]

Other systems

In addition to the six systems that reached tropical storm status, four other tropical depressions developed. The first formed northeast of Bermuda on May 5, marking the third consecutive year in which a tropical cyclone originated before June. The depression was absorbed by a frontal boundary on May 7. Another tropical depression developed in the Bay of Campeche on June 13. Drifting slowly northward and westward, the system made landfall in southern Texas on June 16 and dissipated the following day. The next tropical depression formed in the vicinity of the Azores on July 20. After four days, it was absorbed into a frontal system. The final cyclone that failed to tropical storm status developed in the northeastern Gulf of Mexico to the south of Tallahassee, Florida, on August 4. Drifting southwestward over the next few days, the depression dissipated by August 7.[4]

References

- Neal Dorst (1993). "When is hurricane season ?". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Archived from the original on 8 March 2009. Retrieved March 9, 2009.

- Atlantic basin Comparison of Original and Revised HURDAT. Hurricane Research Division; Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory (Report). Miami, Florida: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. February 2014. Retrieved July 26, 2014.

- David Levinson (August 20, 2008). 2005 Atlantic Ocean Tropical Cyclones. National Climatic Data Center (Report). Asheville, North Carolina: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved July 26, 2014.

- Christopher W. Landsea; et al. (December 2012). Documentation of Atlantic Tropical Cyclones Changes in HURDAT. Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory (Report). Miami, Florida: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved July 23, 2014.

- "Atlantic hurricane best track (HURDAT version 2)" (Database). United States National Hurricane Center. May 25, 2020.

- James E. Hudgins (April 2000). Tropical cyclones affecting North Carolina since 1586: An historical perspective (PDF). National Weather Service (Report). Blacksburg, Virginia: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. p. 25. Retrieved September 3, 2015.

- Bernard Bunnemeyer (1914). Monthly Weather Review for 1913 (PDF) (Report). United States Weather Bureau. Retrieved September 4, 2015.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to 1913 Atlantic hurricane season. |