1909 Greater Antilles hurricane

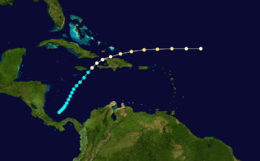

The 1909 Greater Antilles hurricane was a rare, late-season tropical cyclone that caused extensive damage and loss of life in Jamaica and Haiti. Forming out of a large disturbance in early November, the hurricane began as a minimal tropical storm over the southwestern Caribbean Sea on November 8. Slowly tracking northeastward, the system gradually intensified. Late on November 11, the storm brushed the eastern tip of Jamaica before attaining hurricane status. The following afternoon, the storm made landfall in northwest Haiti with winds of 85 mph (140 km/h). After moving over the Atlantic Ocean, the hurricane further intensified and attained its peak winds of 105 mph (165 km/h) on November 13. The system rapidly transitioned into an extratropical cyclone the following day before being absorbed by a frontal system northeast of the Lesser Antilles.

| Category 2 hurricane (SSHWS/NWS) | |

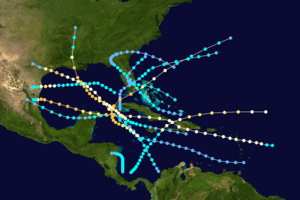

Track map of the hurricane | |

| Formed | November 8, 1909 |

|---|---|

| Dissipated | November 14, 1909 |

| Highest winds | 1-minute sustained: 105 mph (165 km/h) |

| Fatalities | At least 198 direct |

| Damage | $10 million (1909 USD) |

| Areas affected | Jamaica, Cuba, Haiti and the Dominican Republic |

| Part of the 1909 Atlantic hurricane season | |

Including rainfall from the precursor to the hurricane, rainfall in Jamaica peaked at 114.50 in (2,908 mm) Silver Hill Plantation, making it the wettest tropical cyclone on record in the Atlantic Basin. These extreme rains led to widespread flooding that killed 30 people and left $7 million in damage throughout the country. The worst damage in Haiti was caused by rains exceeding 24 in (610 mm) that led to catastrophic flooding. At least 166 people are known to have been killed in the country; however, reports indicate that hundreds likely died during the storm.

Meteorological history

The origins of the 1909 Greater Antilles hurricane are unclear, but are believed to have begun with a large, slow-moving storm system near Jamaica in early November.[1] By November 8, it was classified as a tropical storm and was situated over the southwestern Caribbean Sea, north of Panama.[2] A ship in the vicinity of the system recorded an atmospheric pressure of 1004 mbar (hPa; 29.68 inHg).[3] Slowly moving northeastward, an unusual direction for a Caribbean cyclone, the storm gradually intensified. The forward motion of the system steadily increased on November 10 as it headed towards Jamaica. Late on November 11, the system brushed the eastern tip of Jamaica as a strong tropical storm, with maximum winds estimated at 70 mph (120 km/h). Several hours later, the storm intensified into what would now be classified a Category 1 hurricane on the Saffir–Simpson Hurricane Scale.[2] During the afternoon of November 12, the hurricane made landfall in northern Haiti, in Nord-Ouest, with winds of 85 mph (140 km/h). After briefly moving over land, the storm entered the Atlantic Ocean and turned east-northeast and further accelerated.[2]

Early on November 13, the hurricane further intensified to the equivalent of a Category 2 system and attained peak winds of 105 mph (165 km/h).[2] No barometric pressure was recorded at the time of peak intensity since it occurred over water and away from any ships.[3] In an initial analysis of the storm made by meteorologist José Fernández Partagás in 1999, he wrote that at the storm's peak, it was a strong tropical storm, not a hurricane. In a report, it was stated that "It was a difficult case for the author [Partagás] to decide whether or not to upgrade to a hurricane".[4] It was not until the Atlantic hurricane database re-analysis reached 1909 in February 2004 that the storm was designated as a hurricane.[2][5] By November 14, the storm began to weaken as it turned nearly due east.[2] Later that day, it quickly transitioned into an extratropical cyclone before being absorbed by a frontal system northeast of the Lesser Antilles.[1][2]

Impact

| Precipitation | Storm | Location | Ref. | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rank | mm | in | |||

| 1 | 3429.0 | 135.00 | Nov. 1909 Hurricane | Silver Hill Plantation | [6] |

| 2 | 1524.0 | 60.00 | Flora 1963 | Silver Hill | [7] |

| 3 | 1057.9 | 41.65 | Michelle 2001 | [8] | |

| 4 | 950.0 | 37.42 | Nicole 2010 | Negril | [9] |

| 5 | 938.3 | 36.94 | Gilda 1973 | Top Mountain | [7] |

| 6 | 863.6 | 34.00 | June 1979 T.D. | Western Jamaica | [10] |

| 7 | 823.0 | 32.40 | Gilbert 1988 | Interior mountains | [8] |

| 8 | 720.6 | 28.37 | Ivan 2004 | Ritchies | [11] |

| 9 | 713.5 | 28.09 | Sandy 2012 | Mill Bank | [12] |

| 10 | 690.9 | 27.20 | Isidore 2002 | Cotton Tree Gully | [13] |

Prior to becoming a tropical storm, the precursor low had been producing heavy rainfall across Jamaica since November 5. Further rains fell as the system intensified and neared the country. Between November 5 and 11, the system produced 30.45 in (773 mm) of rain in Kingston. More extreme rains fell upon the Silver Hill Plantation, where 114.50 inches (2,908 mm) of rain accumulated in the five-day period of November 5–9, with eight-day totals from November 4–11 reaching 135.00 inches (3,429 mm).[14] This rainfall triggered severe flooding. Roughly 500,000 banana plants were lost as a result of the floods, about 20% of the entire country's yield.[1] Around Kingston, the waterworks was destroyed and several tunnels and railways were blocked by landslides. Many bridges and roads were also damaged or destroyed. This led to many towns being isolated and hampered rescue efforts. Flood waters in the town of Annott Bay reached 3 ft (0.91 m).[15] Throughout Jamaica, the flooding killed 30 people and damage was estimated at $7 million (1909 USD).[16] Following the severe flooding, the Jamaican government allocated about $150,000 in funds for damage repair.[15]

In nearby Haiti, the damage from the hurricane was catastrophic as torrential rains,[1] reported to have exceeded 24 in (610 mm),[17] triggered widespread flooding and landslides throughout the country.[1] Initial reports from Haiti were slow to reach the news media as most roads were flooded or destroyed. Several days after the hurricane's passage, reports began to indicate that immense damage had taken place due to the storm. The city of Gonaïves was completely flooded after a nearby river overflowed its banks. Residents sought safety from the flood waters in the upper floors and roofs of their homes. Sixteen people were killed in the city after a bridge was destroyed by the swollen river. The Tonazeau River near Port-au-Prince also topped its banks, inundating nearby areas.[18]

Along the Yaqui River, unprecedented flooding led to the creation of a large lake, estimated to be 30 mi (48 km) long and up to 80 ft (24 m) deep. Many villages were destroyed by the floods, with hundreds of fatalities expected to result from the storm.[19] Monetary losses for Haiti following the disaster are scarce, with the only known damage estimate being $3 million. However, the true damage cost from the hurricane is likely much higher.[20] At least 166 fatalities are known as a result of the storm in Haiti;[21] however, many reports state that several hundred people likely perished during the storm.[19] Most of the fatalities took place in the Nord-Ouest, where 150 victims were identified.[22]

See also

- 1909 Atlantic hurricane season

- List of notable tropical cyclones

- Lists of tropical cyclones

- List of wettest tropical cyclones

References

- General

- Partagás, José Fernández; Diaz, H. (1999). A Reconstruction of Historical Tropical Cyclone Frequency in the Atlantic from Documentary and other Historical Sources Part VI: 1909-1910. Climate Diagnostics Center.

- Specific

- Partagás, p. 20

- Hurricane Research Specialists Division (2010). "Easy-to-Read HURDAT 1851-2009". National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on 15 May 2010. Retrieved May 12, 2010.

- Partagás, p. 19

- Partagás, p. 21

- Jack Beven (March 2004). "Comments of and replies to the National Hurricane Center Best-Track Change Committee". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved May 15, 2010.

- Paulhaus, J. L. H. (1973). World Meteorological Organization Operational Hydrology Report No. 1: Manual For Estimation of Probable Maximum Precipitation. World Meteorological Organization. p. 178.

- Evans, C. J.; Royal Meteorological Society (1975). "Heavy rainfall in Jamaica associated with Hurricane Flora 1963 and Tropical Storm Gilda 1973". Weather. Blackwell Publishing Ltd. 30 (5): 157–161. doi:10.1002/j.1477-8696.1975.tb03360.x. ISSN 1477-8696.

- Ahmad, Rafi; Brown, Lawrence; Jamaica National Meteorological Service (January 10, 2006). "Assessment of Rainfall Characteristics and Landslide Hazards in Jamaica" (PDF). University of Wisconsin. pp. 24–27. Retrieved June 6, 2012.

- Blake, Eric S.; National Hurricane Center (March 7, 2011). Tropical Storm Nicole (PDF) (Tropical Cyclone Report). United States National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's National Weather Service. Retrieved May 13, 2012.

- Frank, Neil L.; Clark, Gilbert B. (1980). "Atlantic Tropical Systems of 1979". Monthly Weather Review. American Meteorological Society. 108 (7): 971. doi:10.1175/1520-0493(1980)108<0966:ATSO>2.0.CO;2. ISSN 0027-0644. Retrieved May 13, 2012.

- Stewart, Stacey R.; National Hurricane Center (December 16, 2004). Hurricane Ivan (Tropical Cyclone Report). United States National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's National Weather Service. Retrieved May 13, 2012.

- Blake, Eric S; Kimberlain, Todd B; Berg, Robert J; Cangialosi, John P; Beven II, John L (February 12, 2013). Hurricane Sandy: October 22 – 29, 2012 (PDF) (Tropical Cyclone Report). United States National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's National Weather Service. Archived from the original on February 17, 2013. Retrieved January 29, 2014.

- Avila, Lixion A.; National Hurricane Center (December 20, 2002). Hurricane Isidore (Tropical Cyclone Report). United States National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's National Weather Service. Retrieved May 13, 2012.

- J. L. H. Paulhaus (1973). World Meteorological Organization Operational Hydrology Report No. 1: Manual For Estimation of Probable Maximum Precipitation. World Meteorological Organization. p. 178.

- Press Association (November 15, 1909). "Hurricane In Jamaica". Wanganui Herald. p. 5.

- W. J. Gardiner (November 27, 1909). "A Stormy Island And Its History". New York Times. p. BR744.

- Staff Writer (November 10, 1909). "No Word Received". The Lewiston Daily Sun. p. 9. Retrieved May 13, 2010.

- Staff Writer (November 14, 1909). "Hurricane In Haiti Did Great Damage" (PDF). New York Times. p. C2. Retrieved May 13, 2010.

- Staff Writer (November 23, 1909). "Hundreds Killed In Haiti". Gettysburg Times. p. 2. Retrieved May 13, 2010.

- Alexander E. Barthe (November 25, 1909). "The West Indian Sufferers" (PDF). New York Times. p. 10. Retrieved May 13, 2010.

- Edward N. Rappaport; Jose Fernandez-Partagas; Jack L. Beven (April 22, 1997). "The Deadliest Atlantic Tropical Cyclones, 1492-1996". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved May 13, 2010.

- "January 12 Earthquake in Haiti" (PDF). Ayitigouvenans. 2010. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 6, 2012. Retrieved May 13, 2010.