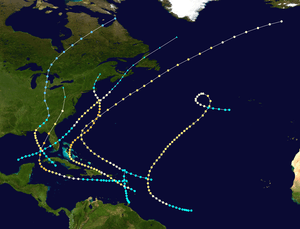

1896 East Coast hurricane

The 1896 East Coast hurricane was a slow-moving tropical cyclone that battered the East Coast of the United States from Florida to New England in mid-October 1896. The fifth tropical cyclone of the 1896 Atlantic hurricane season, it formed on October 7 in the southern Gulf of Mexico, and caused minor damage in Florida while crossing the state two days later. From October 10 through 13, the hurricane drifted northeastward along the coast, reaching its peak intensity as the equivalence of a Category 2 hurricane on the modern-day Saffir–Simpson scale. The hurricane subjected many areas along the East Coast to days of high seas and damaging northeasterly winds, which halted shipping operations.

| Category 2 hurricane (SSHWS/NWS) | |

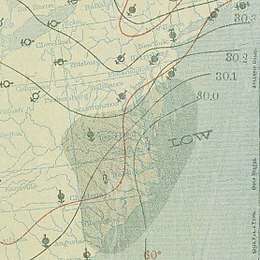

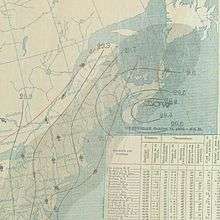

Surface weather analysis of the hurricane off the Mid-Atlantic coast on October 11, 1896 | |

| Formed | October 7, 1896 |

|---|---|

| Dissipated | October 13, 1896 |

| Highest winds | 1-minute sustained: 100 mph (155 km/h) |

| Lowest pressure | 960 mbar (hPa); 28.35 inHg |

| Fatalities | Four |

| Damage | $500,000 (1896 USD) |

| Areas affected | Florida • U.S. East Coast • the Maritimes |

| Part of the 1896 Atlantic hurricane season | |

The Mid-Atlantic coastline experienced flooding storm tides that submerged and heavily eroded Cobb's Island, part of the Virginia Barrier Islands. Hotels and cottages there were extensively damaged, and the hurricane brought about the end of the island's stint as a popular summer resort. Along the Jersey Shore, low-lying railroads were flooded, boardwalks were destroyed, and many beach houses sustained damage. The hurricane did $200,000 in damage to coastal installations on New York's Coney Island. To the north, wind gusts as high as 80 mph (130 km/h) affected eastern New England. Four sailors died in two maritime incidents attributed to the hurricane, and overall damage amounted to $500,000.

Meteorological history

The fifth documented tropical cyclone of the 1896 season was first noted in the southern Gulf of Mexico as a weak tropical storm on October 7.[1] It tracked toward the east-northeast and made landfall in a sparely populated region of Southwest Florida around 00:02 UTC on October 9. The storm crossed the Florida Peninsula and emerged over open water near Sebastian.[1][2] Turning more northeastward, the storm gradually intensified and achieved hurricane intensity on October 10.[1] By that evening, hurricane warnings were hoisted along the East Coast of the United States from Jacksonville, Florida to Boston, Massachusetts.[3]

The unusually slow-moving hurricane attained its peak intensity early on October 11, with estimated maximum sustained winds of 100 mph (155 km/h). Shortly thereafter, it made its closest approach to Cape Hatteras, North Carolina, passing roughly 115 mi (185 km) to the southeast.[1] For several days, the hurricane brushed the coast from Virginia to southern New England with hurricane-force wind gusts.[3] The storm began to weaken as it slowly gained latitude. Unnseasonably cool temperatures were recorded in New York City as the system passed offshore, suggesting that it had begun losing its tropical characteristics.[3] By 00:00 UTC on October 14, the storm completed its transition into an extratropical cyclone,[1] and no winds stronger than tropical storm-force were observed north of 41°N.[4] A little over a day later, the hurricane's extratropical remnants struck the coast of central Nova Scotia before dissipating on October 16.[1]

Impact

The relatively weak storm caused little damage upon landfall in Florida, though some coastal flooding occurred near Punta Gorda. An apparent tornado north of the storm's track destroyed a home and an outbuilding.[2][5] Northeasterly gales and high tides affected northeastern portions of the state, including Fernandina, where lumber docks were flooded and parts of the Florida Central and Peninsular Railroad were washed out. Street flooding also plagued St. Augustine, but no major damage was reported there.[6]

Strong northerly gales affected the Outer Banks of North Carolina for three days, peaking at 72 mph (116 km/h) in Kitty Hawk on October 11.[7] Winds reached 70 mph (110 km/h) along the Virginia Capes and 40 mph (65 km/h) farther west at Norfolk. Just inside the capes, a cargo ship called the Henry A. Litchfield ran aground on October 12. Storm surge flooding inundated the Cape Henry Light keeper's house and washed away telegraph poles, while severe damage was reported in Virginia Beach.[8] There, high waves destroyed fishing nets and crumbled bulkheads, but advance warning of the storm allowed most vessels to safely ride out the storm in port.[9] Near Norfolk, floodwaters damaged the banks of the Dismal Swamp Canal to the point of collapse in some spots.[8] The storm inundated the Virginia Barrier Islands, completely covering Cobb's Island, a popular summer resort, to a depth of at least 1 ft (0.30 m). Pounding waves, reportedly 40 ft (12 m) high, crushed some cottages and partially buried others in sand, while depositing numerous boats in the middle of the island.[10] United States Life-Saving Service crews rescued two women in imminent danger of being swept out to sea. As waters rose, residents fled to the upper stories of their homes to await rescue by lifeguards. The Cobb's Island Hotel was a complete loss,[8] and almost every building on the island sustained some degree of damage. The storm claimed about 50 acres (20 ha) of Cobb's Island, reducing its size by two-thirds; subsequently, the inhabitants abandoned the island, and its use as a resort ended.[10] Due to the slow-moving nature of the hurricane, the flooding persisted for two days before receding.[8]

Along the coast of Delaware near Cape Henlopen, the schooner Luther A. Roby was driven aground and broken up by the pounding surf. Three crew members died in the wreck, and five others safely reached shore with the help of rescue workers.[11] Offshore, the steamship Baron Innerdale was damaged in the storm, and one of the crew members was swept overboard.[12]

The worst effects were observed along the Northeastern shoreline from New Jersey to New England. In these areas, coastal flooding and persistent gales inflicted an estimated $500,000 in damage to beachfront property. Many small houses, seawalls, wharves, and piers were damaged or destroyed.[5][11] Wind gusts along the Jersey Shore reached 75 mph (120 km/h), which unroofed buildings and blew summer cottages off their foundations.[13] Homes and businesses in Asbury Park were bombarded by the debris from a half-mile stretch of boardwalk that was torn apart.[11] Thousands of spectators lined the shoreline there to watch the enormous waves.[13] One of the premier hotels in Sea Isle City was demolished,[11] along with numerous cottages.[13] The storm heavily flooded streets in the city and damaged yachts along the coast.[6] Just south of Sea Isle City, the steamer Spartan went ashore after her captain spent 30 hours fighting the storm at the wheel.[12] In Atlantic City, one amusement pier was heavily damaged by an impact from the dislodged wreckage of a previously sunk schooner,[14] while another was broken up by the surf.[11] Winds in Atlantic City gusted to 55 mph (90 km/h), and floodwaters surrounded some cottages, forcing residents to leave their homes by boat. The railway to Ocean City was washed out, leaving the community temporarily isolated. Railroad tracks were also submerged to the south at Cape May.[6] Farther inland, the winds brought down some few trees and overhead wires.[15] In Millville, high tides caused the Maurice River to overflow and destroy crops in bordering fields.[16]

Hog Island, a barrier island that was mostly washed away by the 1893 New York hurricane,[17] was further eroded by the rough seas. Beaches, pavilions, bath houses, and boardwalks on Coney Island incurred significant damage, with many small buildings along Brighton Beach being "picked up bodily and carried away."[13] Damage on Coney Island was expected to cost at least $200,000.[12] In Far Rockaway, Queens, beachfront houses built on stilts were leveled, while significant flooding extended well inland; multiple hotels were inundated by at least 2 ft (0.61 m) of water.[13] In New England, the storm kept all vessels at port for several days.[13] The strongest recorded winds on land occurred on Block Island, Rhode Island, where gusts reached 80 mph (130 km/h). Elsewhere, winds peaked at 60 mph (97 km/h) on Nantucket, Massachusetts, and 52 mph (84 km/h) at Boston.[3] The storm partially destroyed a seawall and shifted a building off its foundation in Narragansett Pier, Rhode Island.[18] Near South Boston, the storm broke 15 yachts from their moorings and tossed them ashore, sinking several others.[19] The schooner Alsatin sank off Bakers Island; her crew of four was rescued by a passing steamer.[20] At Cohasset, a new lifeboat station constructed by the Massachusetts Humane Society was destroyed.[16] As the former hurricane moved over Nova Scotia, Halifax experienced gusty winds and moderate rainfall.[21]

See also

References

- Specific

- Hurricane Research Division (June 16, 2016). "Atlantic hurricane best track (HURDAT version 2)". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved February 14, 2017.

- Barnes, pp. 78–79

- Partagás, José Fernández (1995). "A Reconstruction of Historical Tropical Cyclone Frequency in the Atlantic from Documentary and other Historical Sources: Year 1896" (PDF). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. pp. 51–53. Retrieved February 14, 2017.

- Hurricane Research Division (May 2015). "Documentation of Atlantic Tropical Cyclones Changes in HURDAT". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved February 14, 2017.

- Henry, A. J. (November 1896). "Local Storms" (PDF). Monthly Weather Review. American Meteorological Society. 24 (11): 398. Bibcode:1896MWRv...24..398H. doi:10.1175/1520-0493(1896)24[398:LS]2.0.CO;2. Retrieved February 14, 2017.

- "Big storm on the coast". The Wilkes-Barre Record. October 12, 1896. p. 1. Retrieved February 14, 2017 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Wind" (PDF). Monthly Weather Review. American Meteorological Society. 24 (11): 362. November 1896. Bibcode:1896MWRv...24Q.362.. doi:10.1175/1520-0493(1896)24[362a:W]2.0.CO;2. Retrieved February 15, 2017.

- Roth, David M. "Virginia Hurricane History: Late Nineteenth Century". Weather Prediction Center. Retrieved February 2, 2017.

- "Damaging winds, surging tides". The Norfolk Virginian. October 13, 1896. p. 1. Retrieved February 28, 2017 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Virginia affairs". The Baltimore Sun. October 20, 1896. p. 7. Retrieved February 3, 2017 – via Newspapers.com.

- Schwartz, p. 108

- "Wrecks on the ocean". Chicago Daily Tribute. October 13, 1896. p. 5. Retrieved February 15, 2017 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Damage done by wind". The Times-Democrat. October 13, 1896. p. 1. Retrieved February 15, 2017 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Storm strikes the Delaware". The Times. October 12, 1896. p. 1. Retrieved February 15, 2017 – via Newspapers.com.

- "A great storm". Harrisburg Telegraph. October 12, 1896. p. 1. Retrieved February 15, 2017 – via Newspapers.com.

- "A swath of ruin". The Philadelphia Inquirer. October 14, 1896. p. 2. Retrieved February 15, 2017 – via Newspapers.com.

- Onishi, Norimitsu (March 18, 1997). "Queens Spit tried to be a resort but sank in a hurricane". The New York Times. Retrieved February 15, 2017.

- "The damage at Narragansett Pier". Harrisburg Daily Independent. October 14, 1896. Retrieved February 15, 2017 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Hurricane spreads ruin along the upper Atlantic Coast". The Courier-Journal. October 13, 1896. p. 1. Retrieved February 15, 2017 – via Newspapers.com.

- "A heroic rescue". Altoona Tribute. October 12, 1896. Retrieved February 15, 2017 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Storm reaches Nova Scotia". The Brooklyn Daily Eagle. October 14, 1896. p. 16. Retrieved February 15, 2017 – via Newspapers.com.

- General

- Barnes, Jay (2007). Florida's Hurricane History. University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 0807858099.

- Schwartz, Rick (2007). Hurricanes and the Middle Atlantic States. Blue Diamond Books. ISBN 0978628004.