1893 New York hurricane

The 1893 New York hurricane, also known as the Midnight Storm,[1] was a powerful and destructive tropical cyclone that struck the New York City area in August 1893. First identified as a tropical storm on August 15, over the central Atlantic Ocean, the hurricane moved northwestward for most of its course, ultimately peaking with maximum sustained winds of 115 mph (185 km/h) and a minimum barometric pressure reading of 952 mbar (hPa; 28.11 inHg). It turned due northward as it approached the U.S. East Coast and struck western Long Island on August 24. It moved inland and quickly deteriorated, degenerating the next day.

| Category 3 major hurricane (SSHWS/NWS) | |

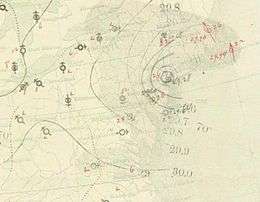

Map of the hurricane on August 24 over New York City | |

| Formed | August 15, 1893 |

|---|---|

| Dissipated | August 25, 1893 |

| Highest winds | 1-minute sustained: 115 mph (185 km/h) |

| Lowest pressure | 952 mbar (hPa); 28.11 inHg |

| Fatalities | At least 34 |

| Areas affected | Eastern United States |

| Part of the 1893 Atlantic hurricane season | |

The storm inflicted severe damage with storm tides as high as 30 ft (9 m). Trees were brought down, houses were demolished, and Hog Island was largely washed away by the cyclone. Several areas suffered extensive effects from the hurricane, and at least 34 sailors lost their lives. The storm is regarded as one of the most severe hurricanes to strike the city.

Meteorological history

The system was first classified as a tropical storm while situated in the central Atlantic Ocean on August 15, 1893. It steadily intensified as it tracked generally toward the west and attained hurricane force. Gradually curving northwestward, the storm continued to gain power and, on August 18, it achieved wind speeds corresponding to Category 2 intensity on the modern-day Saffir-Simpson Hurricane Scale.[2] This scale was devised in 1971 to categorize tropical cyclones based on their maximum sustained winds.[3] The storm is estimated to have maintained winds of approximately 100 mph (155 km/h) for several days as it passed well to the north of the Lesser Antilles. As the hurricane turned more northerly still, approaching the United States, it strengthened to major hurricane intensity, Category 3, on August 22. At this point, it peaked in intensity with winds of 115 mph (185 km/h). The lowest known barometric pressure in relation to the storm was 952 mbar (hPa; 28.11 inHg).[2]

Less than a day later, the storm deteriorated to Category 2 strength.[2] Cape Hatteras, North Carolina experienced the hurricane on the morning of August 23 while its center passed less than 100 mi (160 km) offshore. Heading nearly due northward, the cyclone skimmed the New Jersey coastline, passing just east of Atlantic City,[4] and weakened further to Category 1 status.[2] On August 23 the storm was one of four hurricanes occurring simultaneously within the Atlantic Ocean.[5] On August 24 the storm moved ashore on western Long Island, in the New York City area. At 1200 UTC that day, while centered just inland, its maximum winds were estimated to have been 85 mph (140 km/h). It progressed northward through New England, quickly weakening. It was briefly downgraded to a tropical storm before becoming extratropical.[2] It dissipated fully on August 25, near the mouth of the Saint Lawrence River.[4]

Impact

Winds from the storm exceeded 50 mph (80 km/h) at Atlantic City and New York, initially blowing from the northeast before shifting southwesterly.[4] The hurricane wrought severe destruction,[6] described by The New York Times on August 25 as "a mighty war of winds and a great tumbling of chimneys" and 3.82 inches (97 mm) of rain falling from 8:00 PM Wednesday to 8:00 AM Thursday.[7] A 30 ft (9 m) storm surge struck the shore, demolishing structures as large as an elevated railway.[6] The storm has been cited as an example of a noteworthy New York City tropical cyclone.[8] The cyclone is known for largely destroying Hog Island, a developed resort island along the southern Long Island coast, which had been as long as about 1 mi (1.6 km) in the 1870s.[9]

The worst of the damage was reportedly confined to a 50 mi (80 km) area surrounding New York City. In a 12-hour period, 3.82 in (97 mm) of precipitation fell, breaking the daily rainfall record. Hundreds of thousands of dollars in losses accompanied the severe impact. Low-lying areas of the city, particularly those near the coast, were flooded. Roofs and chimneys were ripped off buildings and windows were broken in many homes and businesses. In Central Park, "More than a hundred noble trees were torn up by the roots, and branches were twisted off everywhere."[7] The park was devastated and thousands of dead birds fell to the ground after being washed out of, or drowned in, their nests. Groups of children gathered the birds and picked them up, with the apparent intention of selling them to restaurants.[7] The storm took the lives of 34 sailors as vessels were blown ashore and men swept overboard. The tugboat Panther, towing two coal barges, was wrecked; 17 crew members perished and three lived.[7]

High winds brought down telegraph wires and left the city almost entirely cut off from communication with outside locations. At Coney Island, the storm completely destroyed many buildings, walkways, piers, and beach resorts. Brighton Beach was hit particularly hard. The raging seas swept inland, washing out tracks of the Marine Railway.[7] Bathing houses were moved a great distance by the cyclone. Near the Sheepshead Bay, Emmons Avenue was heavily damaged. Further to the east, at Greenport, numerous yachts were wrecked and scattered. Corn crops on land were ruined and fruit trees lost their fruits.[7]

At Brooklyn, still an independent city from New York, houses were dismantled and uprooted trees blocked streets. Damage was widespread throughout the area and flood waters reached waist-high levels. The storm was the most severe in years at Jersey City, New Jersey, despite the fact that its damage was moderate. Trees were blown down and cellars filled with water there and in nearby areas, such as Hoboken.[7]

See also

References

- "Chronological List of All Hurricanes which Affected the Continental United States: 1851-2007" (txt). United States National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 12 January 2013.

- National Hurricane Center (2009). "Easy-to-read HURDAT 1851-2008". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved January 30, 2010.

- Jack Williams (May 17, 2000). "Hurricane scale invented to communicate storm danger". USA Today. Retrieved February 3, 2010.

- "1893 Monthly Weather Review" (PDF). National Weather Bureau. 1894. Retrieved January 30, 2010.

- "NOAA Revisits Historic Hurricanes". Hurricane Research Division. Archived from the original on 28 April 2010. Retrieved April 16, 2010.

- Aaron Naparstek (September 4, 2005). "Storm Tracker". New York magazine. Retrieved February 3, 2010.

- "Swept by Wind and Rain". The New York Times. The New York Times. August 25, 1893. Archived from the original on 2017-05-03. Retrieved 2017-05-03 – via Newspapers.com

- Robert Roy Britt (June 1, 2005). "History Reveals Hurricane Threat to New York City". Robert Roy Britt. Retrieved February 3, 2010.

- Norimitsu Onishi (March 18, 1997). "Queens Spit Tried to Be a Resort but Sank in a Hurricane". The New York Times. Retrieved February 3, 2010.