1875 Atlantic hurricane season

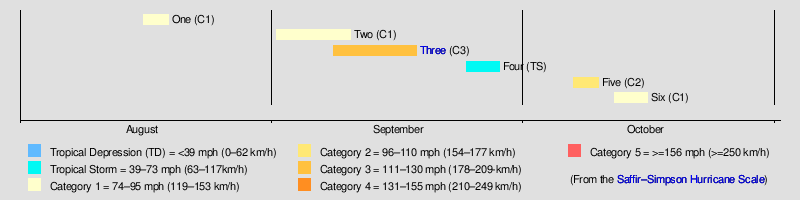

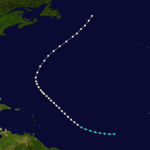

The 1875 Atlantic hurricane season featured three landfalling tropical cyclones. However, in the absence of modern satellite and other remote-sensing technologies, only storms that affected populated land areas or encountered ships at sea were recorded, so the actual total could be higher. An undercount bias of zero to six tropical cyclones per year between 1851 and 1885 has been estimated.[1] There were five recorded hurricanes and one major hurricane – Category 3 or higher on the modern-day Saffir–Simpson scale.[2]

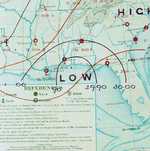

| 1875 Atlantic hurricane season | |

|---|---|

Season summary map | |

| Seasonal boundaries | |

| First system formed | August 16, 1875 |

| Last system dissipated | October 16, 1875 |

| Strongest storm | |

| Name | Three |

| • Maximum winds | 115 mph (185 km/h) (1-minute sustained) |

| • Lowest pressure | 960 mbar (hPa; 28.35 inHg) |

| Seasonal statistics | |

| Total storms | 6 |

| Hurricanes | 5 |

| Major hurricanes (Cat. 3+) | 1 |

| Total fatalities | ~800 |

| Total damage | $5 million (1875 USD) |

Reanalysis of the season for HURDAT – the official database for Atlantic tropical cyclones – was completed by 2011.[3] Of the known 1875 cyclones, both the first and fifth cyclones were first documented in 1995 by Jose Fernandez-Partagas and Henry Diaz. They also proposed large changes to the known track of the sixth system and to the duration of the second storm, as well as more minor changes to the track of third cyclone.[4] The duration of the second system was further amended in 2008.[3]

Although three tropical cyclones made landfall, only one caused significant damage. The season's third known and strongest system, known as the Indianola hurricane, brought devastation to portions of the Lesser Antilles, Greater Antilles, and Texas. It is estimated that the hurricane caused about 800 fatalities, with approximately 300 in the city of Indianola, Texas, alone. The storm left over $5 million (1875 USD) in damage.

Timeline

Systems

Hurricane One

| Category 1 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | August 16 – August 19 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 80 mph (130 km/h) (1-min) |

The first known storm of the season was initially observed by the schooner J. W. Coffin on August 16,[4] with the hurricane situated about 255 mi (410 km) northeast of Little Abaco Island in the Bahamas. Due to sparsity of data, HURDAT indicates that the cyclone maintained intensity as an 80 mph (130 km/h) Category 1 hurricane on the modern day Saffir–Simpson scale, as it tracked north-northeastward to northeastward.[5] The hurricane was last noted offshore Nova Scotia by the bark Electra late on August 19.[4]

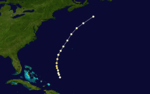

Hurricane Two

| Category 1 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | September 1 – September 10 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 80 mph (130 km/h) (1-min) 982 mbar (hPa) |

A tropical storm developed about 820 mi (1,320 km) west-southwest of the Cabo Verde Islands early on September 1.[5] On September 3, the Spanish brig Engracia became the first ship to encounter the storm.[4] That day, the cyclone intensified into a Category 1 hurricane while moving northwestward. The hurricane peaked with maximum sustained winds of 80 mph (130 km/h).[5] Early on September 6, the steamship Caribbean observed a barometric pressure of 982 mbar (29.0 inHg),[4] the lowest in relation to the storm. On September 7, the cyclone began moving northward and then northeastward later that day. The storm was last noted by the Knoch Train late on September 10,[4] about 450 mi (720 km) east of Newfoundland.[5]

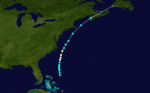

Hurricane Three

| Category 3 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | September 8 – September 18 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 115 mph (185 km/h) (1-min) 955 mbar (hPa) |

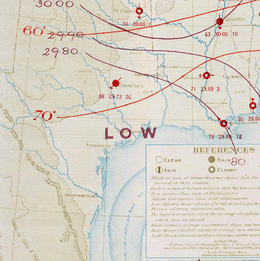

The storm was first observed on September 1 to the southwest of Cabo Verde by the ship Tautallon Castle.[6] However, HURDAT does not indicate a tropical cyclone until the system was situated east of Barbados on September 8. The hurricane moved westward and passed between Martinique and St. Lucia on the following day. The hurricane slowly deepened in the Caribbean Sea while gradually curving northwestward. Late on September 12 and early on September 13, the cyclone brushed the Tiburon Peninsula of Haiti. On September 13, the storm made a few landfalls on the southern coast of Cuba before moving inland over Sancti Spíritus Province. The system emerged into the Gulf of Mexico near Havana and briefly weakened to a tropical storm. Thereafter, the storm slowly re-intensified and gradually turned westward. At 12:00 UTC on September 16, the hurricane became a Category 3 hurricane with winds peaking at 115 mph (185 km/h), based on land observations.[5] The minimum barometric pressure was 955 mbar (28.2 inHg), based on the pressure–wind relationship developed by National Hurricane Center meteorologist Dan Brown in 2006.[3] Seven hours later, the hurricane made landfall near Indianola, Texas. The storm quickly weakened and turned northeastward, before dissipating over Mississippi on September 18.[5]

The hurricane brought heavy rainfall to several islands of the Lesser Antilles, especially Saint Vincent. Flooding and landslides caused severe damage to crops and roads. Most streets of Kingstown were inundated with 3 ft (0.91 m) of water, while two bridges and several homes were swept away. Outside the capital city, water swept away more than 30 homes in total from Hopewell and Mesopotamia. Four people drowned in the latter,[7] with five other fatalities in Queensbury.[8] In Martinique, 20 deaths occurred after the ship Codfish sank in the harbor.[7] Navassa Island experienced strong winds, heavy rainfall, and waves that topped the 75 ft (23 m) cliffs. Many trees were downed and several homes were destroyed.[9] Strong winds and above normal tides in Cuba left damage across the island, especially in Júcaro and Santa Cruz del Sur.[4] In Texas, Old Velasco was completely leveled, while the town of Indianola was nearly destroyed.[6] Three-quarters of the buildings in Indianola were washed away and the remaining structures were in a state of ruin, with only eight buildings left undamaged.[10] Approximately 300 people were killed in Indianola.[11] The town was again almost completely destroyed by another hurricane in 1886 and subsequently abandoned. Four people drowned after the two lighthouses at Pass Cavallo were swept away. At Galveston, several houses and a railroad bridge were destroyed, and a ship, the Beardstown sunk in Galveston Bay.[6] The town suffered about $4 million in damage and 30 deaths.[12][13] Overall, the hurricane left an estimated 800 deaths.[11]

Tropical Storm Four

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | September 24 – September 28 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 60 mph (95 km/h) (1-min) |

A tropical storm formed in the west-central Gulf of Mexico on September 24. After initially moving northwestward, the storm curved east-northeastward by the following day. The cyclone peaked with maximum sustained winds of 60 mph (95 km/h), and due to lack of data, was believed to have maintained this intensity until making landfall near modern-day Panama City, Florida at 13:00 UTC on September 27. By early September 28, the storm weakened to a tropical depression and soon dissipated near the Florida–Georgia state line.[5] Several locations along the Gulf Coast of the United States reported heavy rainfall, with 6 in (150 mm) and 3 in (76 mm) of precipitation observed in Mobile and New Orleans, respectively.[4]

Hurricane Five

| Category 2 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | October 7 – October 10 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 105 mph (165 km/h) (1-min) |

The schooner Pilot's Pride first encountered this hurricane northeast of the Bahamas on October 7.[4] The system moved just west of due north and intensified into a Category 2 hurricane on the following day. Based on ship reports, the hurricane is estimated to have peaked with maximum sustained winds of 105 mph (165 km/h).[5] The bark Marie was damaged by the storm on October 8 and returned to port for repairs.[4] Early on October 9, the cyclone curved northeastward and weakened to a Category 1 hurricane. The storm was last noted to the southeast of Sable Island late on October 10.[5]

Hurricane Six

| Category 1 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | October 12 – October 16 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 80 mph (130 km/h) (1-min) |

The final known tropical cyclone of the season was first encountered by the schooner Lillie Taylor early on October 12,[4] about 150 mi (240 km) northeast of the Abaco Islands. Moving slowly northward to north-northeastward, the storm slowly strengthened, reaching hurricane intensity on October 14. The system peaked with maximum sustained winds of 80 mph (130 km/h),[5] based on observations from the ship E.E. Ruckett.[3] The cyclone weakened to a tropical storm early on October 15 and began accelerating northeastward. Early October 16, the storm made landfall near Yarmouth, Nova Scotia, with winds of 60 mph (95 km/h), shortly before transitioning into an extratropical cyclone.[5] Several locations along the East Coast of the United States reported heavy rainfall.[4]

See also

References

- Christopher W. Landsea; et al. (2004). "The Atlantic hurricane database re-analysis project: Documentation for the 1851–1910 alterations and additions to the HURDAT database". Hurricanes and Typhoons: Past, Present and Future. New York City, New York: Columbia University Press. pp. 177–221. ISBN 0-231-12388-4.

- Atlantic basin Comparison of Original and Revised HURDAT. Hurricane Research Division; Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory (Report). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. April 2017. Retrieved May 16, 2017.

- Christopher W. Landsea; et al. Documentation of Atlantic Tropical Cyclones Changes in HURDAT. Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory (Report). Miami, Florida: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved January 8, 2016.

- Jose Fernández-Partagás and Henry F. Diaz (1995). A Reconstruction of Historical Tropical Cyclone Frequency in the Atlantic from Documentary and other Historical Sources 1851-1880 Part II: 1871-1880 (PDF). Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory. Climate Diagnostics Center, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved May 16, 2017.

- "Atlantic hurricane best track (HURDAT version 2)" (Database). United States National Hurricane Center. May 25, 2020.

- David M. Roth (January 17, 2010). Texas Hurricane History (PDF). Weather Prediction Center (Report). College Park, Maryland: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved January 17, 2017.

- "A Hurricane". Chicago Tribune. The Times. November 6, 1875. p. 3. Retrieved February 18, 2017 – via Newspapers.com.

- Forwards report of a 'severe storm' [hurricane?] on 9 September 1875 (Report). The National Archives. October 18, 1875. Retrieved February 18, 2017.

- Annual Report of the Secretary of War (Report). United States Signal Service. 1876. p. 339. Retrieved May 16, 2017.

- Helen B. Frantz (June 15, 2010). "Indianola Hurricanes". Texas State Historical Association. Retrieved January 17, 2017.

- Edward N. Rappaport; Jose Fernandez-Partagas (May 28, 1995). "The Deadliest Atlantic Tropical Cyclones, 1492-1996". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved May 16, 2017.

- "The Gulf Cyclone". Chicago Inter Ocean. September 24, 1875. p. 2. Retrieved May 16, 2017 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Galveston". Pittsburgh Commercial. September 25, 1875. p. 1. Retrieved May 16, 2017 – via Newspapers.com.