15 cm Ring Kanone C/72

The 15 cm Ring Kanone C/72 was a fortress and siege gun developed after the Franco-Prussian War and used by Germany and Portugal before and during World War I.

| 15 cm Ring Kanone C/72 | |

|---|---|

_(cropped).jpg) | |

| Type | Fortress gun Siege gun |

| Place of origin | |

| Service history | |

| In service | 1872-1918 |

| Used by | |

| Wars | World War I |

| Production history | |

| Designer | Krupp |

| Designed | 1872 |

| Manufacturer | Krupp |

| Produced | 1872 |

| Specifications | |

| Mass | Travel: 7,340 kg (16,180 lb) Combat: 4,930 kg (10,870 lb) |

| Barrel length | 3.44 m (11 ft 3 in) L/23[1] |

| Shell | Separate-loading, bagged charges and projectiles |

| Shell weight | 27.7 kg (61 lb 1 oz)[2] |

| Caliber | 149.1 mm (5.87 in) |

| Breech | Horizontal sliding-block |

| Recoil | None |

| Carriage | Box trail |

| Elevation | -5° to +37°[1] |

| Traverse | None |

| Rate of fire | 2 rpm |

| Muzzle velocity | 485 m/s (1,590 ft/s)[2] |

| Maximum firing range | 8 km (5 mi)[1] |

History

After the Franco-Prussian War, the Army began to study replacements for its cast bronze 15 cm Kanone C/61 and steel 15 cm Kanone C/64 breech loaded cannons. Although Prussian artillery had outclassed their French rivals during the war the breech mechanism the C/64 used was weak and there was a tendency for barrels to burst due to premature detonation of shells. In 1872 a new gun which retained the same 149.1 mm (5.87 in) caliber as the previous gun was designed and placed in production. The new gun designated the 15 cm Ring Kanone C/72 was assigned to fortress and siege artillery battalions of the Army. Each artillery battery consisted of four guns with four batteries per battalion.[3]

Design

The C/72 was a typical built-up gun constructed of steel with a central rifled tube, reinforcing layers of hoops, and trunnions. The C/72 featured a new breech which although similar to the breech of the C/64 had a semi-circular face which allowed the gun to avoid the stress fractures which caused catastrophic failures in its square blocked predecessor. This type of breech was known as a cylindro-prismatic breech which was a predecessor of Krupp's horizontal sliding-block and the gun used separate-loading, bagged charges and projectiles.[3]

The C/72 was fairly conventional for its time and most nations had similar guns such as its Russian cousin the 6-inch siege gun M1877 or the Italian Cannone da 149/23. Like many of its contemporaries, the C/72 had a tall and narrow box trail carriage built from bolted iron plates with two wooden 12-spoke wheels. The carriages were tall because the guns were designed to sit behind a parapet with the barrel overhanging the front in the fortress artillery role or behind a trench or berm in the siege role. Like its contemporaries, the C/72's carriage did not have a recoil mechanism or a gun shield. However, when used in a fortress the guns could be connected to an external recoil mechanism which connected to a steel eye on a concrete firing platform and a hook on the carriage between the wheels. For siege gun use a wooden firing platform could be assembled ahead of time and the guns could attach to the same type of recoil mechanism.[1] A set of wooden ramps were also placed behind the wheels and when the gun fired the wheels rolled up the ramp and was returned to position by gravity. There was also no traverse so the gun had to be levered into position to aim. A drawback of this system was the gun had to be re-aimed each time which lowered the rate of fire. For transport, the gun was broken down into two loads 4,560 kg (10,050 lb) and 2,780 kg (6,130 lb) for towing by horse teams or artillery tractors.[1]

World War I

The majority of military planners before the First World War were wedded to the concept of fighting an offensive war of rapid maneuver which in a time before mechanization meant a focus on cavalry and light horse artillery firing shrapnel shells. Since the C/72 was heavier and wasn't designed with field use in mind it was employed as a fortress gun.[1]

Although the majority of combatants had heavy field artillery prior to the outbreak of the First World War, none had adequate numbers of heavy guns in service, nor had they foreseen the growing importance of heavy artillery once the Western Front stagnated and trench warfare set in. The theorists hadn't foreseen that trenches, barbed wire, and machine guns had robbed them of the mobility they had been counting on and like in the Franco-Prussian and Russo-Turkish war the need for high-angle heavy artillery reasserted itself. Since aircraft of the period were not yet capable of carrying large diameter bombs the burden of delivering heavy firepower fell on the artillery. The combatants scrambled to find anything that could fire a heavy shell and that meant emptying the fortresses and scouring the depots for guns held in reserve. It also meant converting coastal artillery and naval guns to siege guns by either giving them simple field carriages or mounting the larger pieces on rail carriages.[4]

A combination of factors led the Germans to issue C/72's to their frontline troops:

- An underestimation of artillery losses during the first two years of the war and an inadequate number of replacement guns being produced.

- Many artillery pieces were neither tall enough or capable of the high-angle fire necessary to fire from entrenched positions.

- Few light field-artillery pieces had the range or fired a large enough projectile to be useful in an indirect fire role.

Although new guns with superior performance were introduced the C/72's remained in service until the end of the war due to the number in service and a lack of replacements. However, their poor range eventually became a handicap.[1]

In 1886, Portugal bought several C/72 artillery pieces and they were still in use by the time the Great War began. They were initially deployed in forts around the city of Lisbon, but during the war they were moved to batteries elsewhere, like in neighboring city of Setúbal and the islands of Azores and Madeira, for coastal defensive duties.[5]

Photo Gallery

_(cropped).jpg) French soldiers with a captures C/72.

French soldiers with a captures C/72..jpg) Carriage and elevation mechanism details for the C/72.

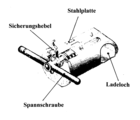

Carriage and elevation mechanism details for the C/72. The breech block of the C/72.

The breech block of the C/72.

References

- Fleischer, Wolfgang (February 2015). German artillery:1914-1918. Barnsley. p. 60. ISBN 9781473823983. OCLC 893163385.

- Handbuch fur die Offiziere der Königlich Preußiſchen Artillerie (2nd ed.). Elsner. 1877.

- Jäger, Herbert (2001). German artillery of World War One. Marlborough: Crowood Press. pp. 10–18. ISBN 1861264038. OCLC 50842313.

- Hogg, Ian (2004). Allied artillery of World War One. Ramsbury: Crowood. pp. 129–134 & 218. ISBN 1861267126. OCLC 56655115.

- Marquês de Sousa, Pedro (2017). A Nossa Artilharia na Grande Guerra: 1914-1918. p. 252. ISBN 9789896584986. OCLC 1031381786.