Tank gun

A tank gun is the main armament of a tank. Modern tank guns are large-caliber high-velocity guns, capable of firing kinetic energy penetrators, high explosive anti-tank rounds, and in some cases guided missiles. Anti-aircraft guns can also be mounted to tanks.

As the tank's primary armament, they are almost always employed in a direct fire mode to defeat a variety of ground targets at all ranges, including dug-in infantry, lightly armored vehicles, and especially other heavily armored tanks. They must provide accuracy, range, penetration, and rapid fire in a package that is as compact and lightweight as possible, to allow mounting in the cramped confines of an armored gun turret. Tank guns generally use self-contained ammunition, allowing rapid loading (or use of an autoloader). They often display a bulge in the barrel, which is a bore evacuator, or a device on the muzzle, which is a muzzle brake.

History

World War I

.jpg)

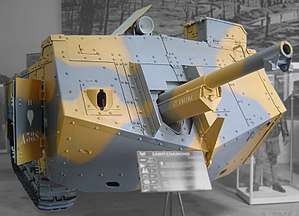

The first tanks were used to break through trench defences in support of infantry actions particularly machine gun positions during the First World War and they were fitted with machine guns or high explosive firing guns of modest calibre. These were naval or field artillery pieces stripped from their carriages and mounted in sponsons or casemates on armored vehicles. The early British Mark I tanks of 1916 used naval 57 mm QF 6 pounder Hotchkiss mounted at the sides in sponsons. These guns proved too long for use in the British tank designs as they would come into contact with obstacles and the ground on uneven terrain, and the succeeding Mark IV tank of 1917 was equipped with the shortened 6 pounder 6 cwt version which can be considered the first specialised tank gun. The first German tank, the A7V, utilized 57 mm Maxim-Nordenfelt fortification guns captured from Belgium and Russia, but mounted at the front. The early French Schneider CA1 mounted a short 75 mm mortar on one side, while the Saint-Chamond mounted a standard 75 mm field gun in the nose. The thin armour of the tanks meant that such weapons were effective against other vehicles, though the Germans fielded few tanks anyway and the Allied tanks concentrated on anti-infantry and infantry support activities.

World War II

This thinking remained pervasive into the dawn of World War II, when most tank guns were still modifications of existing artillery pieces, and were expected to primarily be used against unarmored targets. The larger caliber, shorter range artillery mounting did not go away however. Tanks intended specifically for infantry support (the infantry tanks), expected to take out emplacements and infantry concentrations, carried large calibre weapons to fire large high-explosive shells—though these could be quite effective against other vehicles at close ranges. In some designs - for example, M3 Lee, Churchill, Char B1 - the larger bore weapons were mounted within the tank hull while a second gun for use against tanks was fitted in a turret.

However, other strategists saw new roles for tanks in war, and wanted more specifically developed guns tailored to these missions. The ability to destroy enemy tanks was foremost on their minds. To this end, the emerging anti-tank gun designs were modified to fit tanks. These weapons fired smaller shells, but at higher velocities with higher accuracy, improving their performance against armor. Such light guns as the QF 2-pounder (40 mm) and 37 mm equipped British cruiser tanks and infantry tanks in the late 1930s. These weapons lacked a good high-explosive shell for attacking infantry and fortifications, but were effective against the light armor of the time.

World War II saw a leapfrog growth in all areas of military technology. Battlefield experience led to increasingly powerful weapons being adopted. Guns with calibres from 20 mm to 40 mm soon gave way to 50 mm, 75 mm, 85 mm, 88 mm, 90 mm and 122 mm calibre. In 1939, the standard German panzer had either a 20 mm or 37 mm medium-velocity weapon, but by 1945 long-barrelled 75 mm and 88 mm high-velocity guns were common. The Soviets introduced their 122 mm in a turreted heavy tank series, the Iosef Stalin tanks. Shells were improved to provide better penetration with harder materials and scientific shaping. All of these meant improvements in accuracy and range, although the average tank had to grow as well to carry the ammunition, mounting, and protection for these powerful guns.

While high velocity tank guns were effective against other tanks, for the most part British tanks moved to a dual purpose 75 mm gun capable of firing a useful HE shell; later in the war adding 76mm 17pdr gun armed tanks for better antitank capability.

Many nations devised "tank destroyers" during the war - a vehicle specifically designed for anti-tank work, and armed more heavily than a tank on the same chassis could be. They generally fell into three overlapping categories: improvised modifications of old or captured tanks to render them viable again (such as converting the machine-gun-only Panzer I into the Panzerjäger I), often with haphazard, poorly protected, limited-traverse weapon mounts; the American offensive and mobile reserve model, which favoured lightly-armed open-top vehicles with a rotating turret and a powerful anti-tank-capable gun while relegating true tanks to infantry support role (exemplified by the M10 tank destroyer); and the casemate gun mount model, which often allowed the resultant vehicle to be hard to hit and have a well-sloped and heavily armoured glacis plate (for instance, the SU-100). The relative superiority in armament of tank destroyers was only relative, however: for instance, the SU-85 was a casemate-type TD on the T-34 chassis that was rendered obsolete once the basic T-34 switched from the 76 mm gun to the same 85 mm cannon, producing the T-34-85.

After World War II

By the end of the war the variety in tank designs was narrowed and the concept of the main battle tank emerged. After World War II, the race to increase caliber slowed. Slight increases were made between tank generations. In the West, guns of around 90 mm gave way to the ubiquitous 105 mm L7. This lasted a long while with a shift to 120 mm in the late 1970s and early 80s (the UK changed in the late 60s with their Chieftain tank). In the East, the 85 mm quickly yielded to the 100 mm and 115 mm U-5TS gun, with the 125 mm caliber now standard. Most of the improvements were instead made in ammunition and fire control systems.

With kinetic energy penetrator rounds, solid shot and armour-piercing shell gave way to armour-piercing discarding sabot (APDS) (a product of 1944), and fin-stabilized (APFSDS) rounds with tungsten or depleted uranium penetrators. Parallel developments brought rounds based on chemical energy; High explosive squash head (HESH), and shaped-charge High explosive anti-tank (HEAT), with penetrating power independent of muzzle velocity or range.

Stadiametric range-finders were successively replaced by coincidence and laser rangefinders. Accuracy of modern tank guns is improved over earlier weapons by computerized fire control systems, wind sensors, and muzzle referencing systems which compensate for barrel warping, wear and temperature. Fighting capability at night, in poor weather, and smoke was improved by infrared, light-intensification, and thermal imaging equipment.

Technology of the guns themselves has had only a few innovations. Throughout the history of tank guns, they have almost exclusively been rifled weapons, however most modern tanks now use smoothbore guns. Rifling of the barrel imparts spin on the projectile, improving ballistic accuracy. The best traditional antitank weapons have been kinetic energy rounds, whose penetrating power and accuracy decrease with range. For longer ranges high explosive anti-tank rounds are more effective, but accuracy is limited; for extremely long ranges cannon-launched guided projectiles (CLGPs) are considered more accurate.

The use of the autoloader has been a development favoured by some nations and not others. Some countries adopted it as a means to keep the overall size of the tank down. Interest has also been shown as a means to protect the crew by separating them further from the gun and ammunition. For example, an autoloader allows the use of an unmanned turret in the T-14 Armata.

Smoothbore

In the 1960s smoothbore tank guns were developed by the Soviet Union and later by the experimental US–FRG MBT-70 project. Based on their experience with the gun/missile system of the BMP-1, the Soviets produced the T-64B main battle tank, with an auto-loaded 2A46 125 mm smoothbore high-velocity tank gun, capable of firing APFSDS ammunition as well as ATGMs. Similar guns continue to be used in the latest Russian T-90, Ukrainian T-84, and Serbian M-84AS MBTs. The German company Rheinmetall developed a more conventional 120 mm smoothbore tank gun which can fire LAHAT missiles, adopted for the Leopard 2, and later the U.S. M1 Abrams. The chief advantages of smoothbore designs are their greater suitability for fin stabilised ammunition and their greatly reduced barrel wear compared with rifled designs. Much of the difference in operation between smoothbore and rifled guns shows in the type of secondary ammunition that they fire, with a smoothbore gun being ideal for firing HEAT rounds (although specially designed HEAT rounds can be fired from rifled guns) and rifling being necessary to fire HESH rounds.

Most modern main battle tanks now mount a smoothbore gun. A notable exception are the tanks of the British Army which used the 120mm Royal Ordnance L11A5 rifled gun until the 1990s; it was then replaced it with the 120mm L30 rifled gun which remains in service. The Indian Arjun tank uses an Indian-developed 120mm rifled gun.

References

- Ogorkiewicz, Richard. Technology of tanks, Volume 1 (1991 ed.). Macdonald and Jane's Publishers Ltd. pp. 70–71. ISBN 978-0-7106-0595-5.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Tank guns. |

- Specification and Armor Penetration Values of Soviet Tank Guns - up to the end of World War II, at the Russian Battlefield (battlefield.ru).