10 Rillington Place

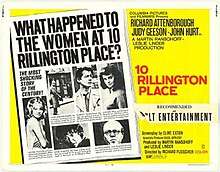

10 Rillington Place is a 1971 British crime drama film directed by Richard Fleischer and starring Richard Attenborough, Judy Geeson, John Hurt and Pat Heywood. It was adapted by Clive Exton from the book Ten Rillington Place by Ludovic Kennedy (who also acted as technical advisor to the production).

| 10 Rillington Place | |

|---|---|

British theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Richard Fleischer |

| Produced by | Leslie Linder Martin Ransohoff |

| Screenplay by | Clive Exton |

| Based on | Ten Rillington Place by Ludovic Kennedy |

| Starring | Richard Attenborough Judy Geeson John Hurt Pat Heywood |

| Music by | John Dankworth |

| Cinematography | Denys Coop |

| Edited by | Ernest Walter |

Production company | Filmways Genesis Productions |

| Distributed by | Columbia Pictures |

Release date |

|

Running time | 111 min |

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Language | English |

The film dramatises the case of British serial killer John Christie, who committed many of his crimes in the titular London terraced house, and the miscarriage of justice involving his neighbour Timothy Evans. Hurt received a BAFTA Award nomination for Best Supporting Actor for his portrayal of Evans.

Plot

The film begins in 1944 with John Christie murdering an acquaintance called Muriel Eady; he lures her to his flat in 10 Rillington Place by promising to cure her bronchitis with a "special mixture", then incapacitates her with Town Gas, strangles her with a piece of rope, and has (implied) sex with her corpse. He buries her in his flat block's communal garden, where a dog uncovers one of his previous victims.

In 1949, Tim and Beryl Evans move into 10 Rillington Place, west London, with their infant daughter Geraldine. Beryl is pregnant again and attempts an abortion by taking some pills. When she informs Tim, they have a violent argument, which Christie breaks up. Soon after, Christie offers to help Beryl terminate the pregnancy. He pretends to read a medical textbook one day in an effort to convince Tim of his expertise. Tim is essentially illiterate and cannot tell that Christie is lying. The Evanses agree to let Christie perform the procedure.

Christie occupies his wife, Ethel, by sending her to his place of work with some paperwork. He grabs his killing tools, makes a cup of tea, and heads upstairs to Beryl. He is interrupted by a couple of builders who arrive to renovate the outbuilding. He lets them in, and when he sees they are well-occupied, he pours a new cup of tea and heads back upstairs. Beryl has a violent reaction to the gas, and Christie punches her in the face to knock her out. He then strangles and sexually assaults her.

When Tim returns, Christie tells him that Beryl died of complications from the procedure. Tim wants to go to the police, but Christie convinces him that he will be seen as an accessory before the fact. Christie suggests that Tim leave town that night, while Christie disposes of Beryl's body. He promises that he will place the baby in the care of a childless couple from East Acton. Tim reluctantly agrees, and leaves the house in the middle of the night. Christie then strangles Geraldine with a tie.

Tim hides out with his aunt and uncle in Merthyr Tydfil, pretending that he is in town on business. He claims that Beryl and the baby are visiting her family in Brighton. Tim's relatives send a letter to Beryl's father, who sends a telegram in response to say that he has not seen Beryl in months. When confronted by his relatives, Tim pretends Beryl had run away with a rich man and then visits the local police station. He confesses to disposing of Beryl's body in the sewer after the botched abortion. Three London police officers lift the manhole, but do not find Beryl's body. A search of 10 Rillington Place eventually uncovers the bodies of Beryl and the baby in the washroom, where Christie hid them.

When Tim is brought back to London, he is charged with the murders of his wife and daughter. In shock, and despondent over the news, he confesses to both crimes, though he is guilty of neither. During his trial, Christie is a key witness. Tim's defence shreds Christie's credibility by revealing that he has a history of theft and violence. Nevertheless, Tim is found guilty and hanged.

Two years after the trial, Ethel begins to fear her husband, and informs Christie she will move out to stay with relatives. When he begs her not to leave him, Ethel implies that he should be in prison. Christie murders her that night and hides her body under the floorboards in their front room. Later, he meets a woman suffering from a migraine in a café. He pretends to be an ex-doctor and promises her a cure. He is next seen putting fresh wallpaper on a wall in his kitchen; it is implied that he has hidden the woman's body in the space behind the wall.

In 1953, Christie is living in a dosshouse. Meanwhile, new tenants are moving into the Christies’ flat. They complain about the awful smell and one of them peels off the wallpaper to find a space behind the wall, where he finds three of Christie's victims. Soon afterwards, Christie is noticed by a police officer in Putney and arrested. The film ends with an intertitle explaining that Christie was hanged and Tim was posthumously pardoned and re-interred in consecrated ground.

Cast

- Richard Attenborough as John Christie

- Judy Geeson as Beryl Evans

- John Hurt as Timothy Evans

- Pat Heywood as Ethel Christie

- Isobel Black as Alice

- Robert Hardy as Malcolm Morris

- Geoffrey Chater as Christmas Humphreys

- André Morell as Judge Lewis

- Sam Kydd as Furniture Dealer

- Gabrielle Daye as Mrs. Lynch

Production

The film was adapted by Clive Exton from the book Ten Rillington Place by Ludovic Kennedy.[1] The film relies on the same argument advanced by Kennedy that Evans was innocent of the murders and was framed by Christie. That argument was accepted by the Crown and Evans was officially pardoned by Home Secretary Roy Jenkins in 1966. The case is one of the first major miscarriages of justice known to have occurred in the immediate postwar period. Most of the script, narrative and character development of it was drawn up in the 1960s.[2]

In 1954, the year after Christie's execution, Rillington Place in Notting Hill, west London, was renamed Ruston Close, but number 10 continued to be occupied. In the 2016 documentary 'Being Beryl' on the UK Blu-ray, the actress Judy Geeson revealed that the family living at number 10 in 1970 were too afraid to move out temporarily in fear of not being allowed back, so exterior scenes and window shots were filmed at the nearby number 7, however in some shots the family clearly agreed Richard Attenborough some access to number 10, certainly in one scene you can see Richard Attenborough standing looking out of the bay window of number 10 (filmed outside from the street) and in other scenes going in and coming out the front door of number 10, (again all filmed from the street), the interior sets were used at Shepperton Studios in London. The house and street were demolished later, and the area has changed beyond all recognition. The area that was once Rillington Place is now occupied by Bartle Road with the exact location of number 10 remaining undeveloped. The plot is now used as a communal garden.

Filming also took place in the village of Merthyr Vale, the real life hometown of Timothy Evans. The pub scenes were filmed at the Victoria Hotel on Burdett Road in east London. The pub was subsequently demolished as part of the redevelopment of the area in 1972–73.

Richard Attenborough, who played Christie in the film, spoke of his reluctance to accept the role: "I do not like playing the part, but I accepted it at once without seeing the script. I have never felt so totally involved in any part as this. It is a most devastating statement on capital punishment."[3] The film was produced by Leslie Linder and Martin Ransohoff.[4] Hangman Albert Pierrepoint, who had hanged both Evans and Christie, served as an uncredited technical advisor on the film to ensure the authenticity of the hanging scene.[5]

Reception

At the time of the film's release, reviews were mixed. Variety's critic wrote "Richard Fleischer has turned out an authenticated documentary-feature which is an absorbing and disturbing picture. But the film has the serious flaw of not even attempting to probe the reasons that turned a man into a monstrous pervert." Praise went to John Hurt for his "remarkably subtle and fascinating performance as the bewildered young man who plays into the hands of both the murderer and the police."[6] Vincent Canby of The New York Times described 10 Rillington Place as "a solemn, earnest polemic of a movie, one with very little vulgar suspense ... The problem with the film is very much the problem with the actual case, which involved small, unimaginative people."[7]

The film has since risen in stature with critics. In a 2009 review, J. Hoberman of the Village Voice wrote, "More highly regarded these days than when it was released in 1971, Richard Fleischer's 10 Rillington Place is a grimly efficient treatment of a once-notorious case".[8] The same year, Keith Uhlich of Time Out gave the film a 5-star review and described it as an "underseen gem".[9]

In an interview with Robert K. Elder in his book The Best Film You've Never Seen, director Sean Durkin states that 10 Rillington Place "depicts this story the way that a piece of journalism might, as opposed to worrying about preconceived notions of what a film should achieve."[10] Tom Hardy of the British Film Institute has noted Attenborough's ability at "getting into the flesh of the paranoid and the distressed", describing the film as a "detailed account of life under the shadow of World War II [which] is powerful and compelling".[11]

John Hurt received a BAFTA Award nomination for Best Supporting Actor.

References

- Variety film review; 10 February 1971.

- Barber, Sian (22 January 2013). The British Film Industry in the 1970s: Capital, Culture and Creativity. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 17. ISBN 978-1-137-30592-3.

- "Christie's ghost returns", The Times (57872), p. 5, 18 May 1970, retrieved 18 April 2009.

- Russell, William B. (2009). Teaching Social Issues with Film. IAP. p. 43. ISBN 978-1-60752-117-4.

- "10 Rillington Place". TCM. Retrieved 22 January 2014.

- "10 Rillington Place Review". Variety. 31 December 1970.

- Canby, Vincent (13 May 1971). "10 Rillington Place Review". The New York Times.

- Hoberman, J (24 June 2009). "10 Rillington Coolly Documents the Case of an Infamous Lady Killer". The Village Voice.

- Uhlich, Keith (25 June 2009). "10 Rillington Place". Time Out.

- Elder, Robert K. (1 June 2013). The Best Film You've Never Seen: 35 Directors Champion the Forgotten Or Critically Savaged Movies They Love. Chicago Review Press. p. 247. ISBN 978-1-61374-929-6.

- Hardy, Phil (1997). The BFI Companion to Crime. University of California Press. p. 319. ISBN 978-0-520-21538-2.