1002 German royal election

The German royal election of 1002 was the decision on the succession which was held after the death of Emperor Otto III without heirs. It was won by Duke Henry IV of Bavaria among accusations of uncustomary practices (bribery and electoral manipulation).

Background

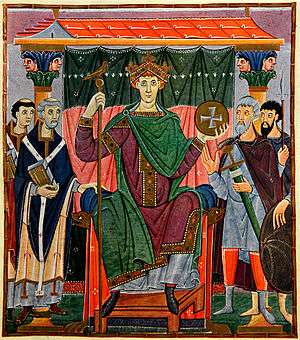

On the 23/24 January 1002, the 21-year-old Emperor Otto III unexpectedly dropped dead from malaria at the Castel Paterno in Italy, without heirs, childless and without any will regulating the succession. As the last male line descendant of Emperor Otto I, the older line of the Liudolfings came to an end with him.

On account of this situation, the election of a new king was no longer a formality controlled by the incumbent king, but became a central political question.

Candidates

The chief candidates to succeed Otto were the Dukes of the Empire, but Eckard I of Meissen also actively competed though he was only a Margrave. According to Thietmar of Merseburg he is meant to have been promoted to the duchy of Thuringia by the Thuringians in a popular election and he had been particularly valued by the deceased Emperor.[1]

Initially, the Conradine Herman II of Swabia appeared the strongest candidate and shortly after the majority of the princes spoke in his favour at Otto III's funeral in Aachen at Easter 1002.

But there was a further candidate among the Dukes: Henry IV of Bavaria, the son of Henry the Wrangler, the only remaining Liudolfing (apart from Henry IV's brother Bruno). The Emperor Otto II had attempted to exclude Henry from any involvement in the government of the Empire and, according to Thietmar of Merseburg, no one close to the dead emperor considered Henry a possible successor except for Siegfried I, Bishop of Augsburg. In fact, Henry had further supporters among the Saxon magnates, who put great value on retaining a ruler from the Saxon house. Henry had a clear claim to the succession and emphasised this by a substantial donation for the funeral, an act which was generally carried out by the legitimate successor. In addition, he made contact with the Salian Otto of Worms, titular Duke of Carinthia, who was a grandson of Otto I. He waived his rights in favour of Henry, although he had put forward his candidature (whether sincerely or tactically is unclear). After this, Henry was the highest-ranking candidate and also the most closely related to Otto III in the male line. Nevertheless, his candidature remained uncertain, since there was no codified rule or even custom which gave remote relatives a right to succeed to the kingship.

The candidature of the Count palatine Ezzo (Ezzonid) is only mentioned in the foundation account of Brauweiler Abbey. Elsewhere it is said that he, Otto III's only brother-in-law and father of Otto's nearest relatives, had received the Imperial regalia from Heribert, Archbishop of Cologne and Archchancellor. According to Vita Bernwardi and Vita Meinwerci, Count Brun of Brunswick (Brunonid) was also a candidate,[2] but this is not reported in any other source.

Robbery of the Imperial regalia

When the caravan with Otto III's body had been led over the Alps by Archbishop Heribert, it reached the borders of Henry's duchy at Polling. Henry displayed great concern for the caravan, but more for his claim and finally he forced Heribert to hand over the Imperial regalia which were being carried with the body. These did not include the Holy Lance, which was the most important reliquary of the Empire. Heribert had sent the Lance ahead, probably out of mistrust of Henry, since he had been part of the close circle of the deceased Emperor who had named Hermann of Swabia as the new King. Henry imprisoned the Archbishop and subsequently also his brother Henry I, Bishop of Würzburg. In this way he eventually gained possession of the Lance as well.

Candidature of Eckard I of Meissen

Probably because of personal esteem which Emperor Otto III had maintained towards Eckard I margrave of Meissen, he entered the competition for the succession after Otto's death. An initial conclave of sixteen Saxon princes and bishops at Frohse on the Elbe, at which Eckard sought a nomination, adjourned without making a nomination after a further meeting had been scheduled to take place at the Royal palace of Werla. A major reason for this decision was the support of Count Lothar of Walbeck, Margrave of Nordmark for Henry. Lothar continued his efforts after the decision at Frohse with Henry of Schweinfurt, whose support Henry had secured by promising him the Duchy of Bavaria.

At Werla, Henry of Schweinfurt kept on working to secure the meeting's support for the absent Henry by promising that Henry would give great rewards in the event of his nomination but also by referring to his connections with the Liudolfing dynasty and his legitimate right to the inheritance. In the latter argument he had the support of Otto's sisters Sophia and Adelaide.

Despite the set-back, Eckard was clearly unfazed. He came to Werla along with his allies, Bishop Arnulf of Halberstadt and Duke Bernard I of Saxony. A little later he went to Hildesheim where he was recognised as the new king by Bishop Bernward of Hildesheim. Then he made his way to Duisburg to meet with Hermann of Swabia there and after that he returned to Paderborn. On 30 April 1002 on the way back he was attacked and killed by Count Siegfried of Northeim with Henry and Udo of Katlenburg in the Pöhlde Palace in Harz. This murder was, apparently, the result of a feud and unconnected to the royal election.

The election of Henry

Immediately after the meeting at Werla, Henry moved towards Mainz with armed forces and got the Archbishop of Mainz Willigis to promise that he would crown him after his successful election in his cathedral, Mainz Cathedral and not in Aachen as usual. Then on 7 June 1002, Henry had the worldly and spiritual princes who were present vote without waiting for the full conclave of electors. Here his Bavarian followers and the Eastern Franks voting for him and the Swabians against him. With that he was elected as king, without the knowledge or participation of the northern and western regions: Lotharingia, Saxony, and Thuringia: Henry's power base consisted of his duchy and the majority of the bishops under the leadership of Archbishop Willigis of Mainz, who carried out the coronation immediately after the election as promised.

While Willigis was responsible for the coronation as archbishop of Mainz, everything else in this election was counter to tradition: the location of the conclave, the fact that Henry did not sit upon the Throne of Charlemagne and of course the fact that not all electors were present at the conclave.

Acknowledgment of the election

The fact that not all electors were present obliged Henry to spend months obtaining submission by means of a royal process. Such a process had been common under the Merovingians but had not been customary for centuries. The course was meant to run through Thuringia, Saxony, Lower Lotharingia, Swabia, Bavaria and Upper Lotharingia, but it was initially held up and rerouted because of the opposition of the Swabians.

Unsurprisingly, Hermann of Swabia refused to recognise the election or the coronation in Mainz, so at the end of June, almost immediately after his coronation, Henry began a campaign against the Conradines march to Strasbourg and then to Reichenau Island by the end of the month.

He travelled on through Bamberg to Kirchberg (near Jena) where the Thuringians paid hommage to him on 20 July 1002 under the leadership of Count William II of Weimar. A few days later, negotiations took place with the Saxon Greats at Merseburg (24–28 July), including most importantly: Duke Bernhard of Saxony, Duke Bolesław I Chrobry of Poland, Margrave Lothar of Nordmark, Count Palatine Frederick of Saxony, and the Bishops Arnulf of Halberstadt and Bernward of Hildesheim. In the end, they agreed to recognise Henry in return for certain concessions. Both sides were able to save face, especially since the Saxons had maintained that after four Saxon rulers, the next king ought to come from their ranks, a condition which Henry as a third generation Duke of Bavaria did not fulfill despite his Saxon ancestry. The agreement encompassed the following points:

- Henry recognised the rights of the Saxons in the German kingdom.

- The Saxons recognised Henry as King.

- Because of their absence the election in Mainz was not binding on the Saxons

- Henry submitted to a separate election as king by the Saxons.

- Duke Bernhard surrendered the Holy Lance to Henry, and paid hommage to him at another coronation.

Henry travelled on past Grona Palace to Paderborn, where the coronation of his wife Cunigunde as Queen took place on 10 August. On 18 August, Henry was reconciled with Archbishop Heribert of Cologne at Duisburg and the Bishops of Lotharingia immediately paid hommage to him. After stops in Nijmegen and Utrecht another coronation took place at Aachen on 8 September, at which the Barons of Lower Lotharingia paid hommage. On 1 October Duke Hermann and the Swabian nobility submitted at Bruchsal. Via Augsburg, Henry went on to Regensburg where his own vassals paid hommage to him between 11 and 24 November. Then he travelled on to Frankfurt am Main and finally to Diedenhofen (Thionville) where he held a Hoftag and an Imperial synod, which he combined with the payment of hommage by the barons of Upper Lotharingia.

Aftermath

Hermann of Swabia, who had not initially recognised Henry's election but had subsequently submitted to him at Bruchsal, died a few months later on 4 May 1003. Henry took over the regency of Hermann's duchy on behalf of his young son Hermann III (a situation which was maintained de jure by his successors until the middle of the century) and he used this position to permanently remove the family of his rival from power.

Henry of Schweinfurt had supported the election of Henry II in return for the promise that he could succeed to Bavaria. However, the new king reneged on this promise, since he could not allow Schweinfurt to have such a powerful position in the southeast of the Empire. Therefore, Henry of Schweinfurt and his close relatives made an alliance with Bolesław I of Poland (who had also submitted to Henry II at Merseburg after an unexplained attack) and Brun, the brother of King Henry. This alliance was defeated in the summer of 1003. Henry of Schweinfurt lost his county and his imperial fiefs and only his personal property was returned to him when he was pardoned in 1004.

References

- Thietmar IV, 45.

- Vita Bernwardi 38 & Vita Meinwerci 7

Sources

- Thietmar of Merseburg: Chronik. Translated by Werner Trillmich. Darmstadt 1957 (Freiherr vom Stein-Gedächtnisausgabe 9). Latin Text in Robert Holtzmann (Ed.) Scriptores rerum Germanicarum, Nova series 9: Die Chronik des Bischofs Thietmar von Merseburg und ihre Korveier Überarbeitung (Thietmari Merseburgensis episcopi Chronicon) Berlin 1935.

Bibliography

- Eduard Hlawitschka. "Die Thronkandidaturen von 1002 und 1024. Gründeten sie im Verwandtenanspruch oder in Vorstellungen von freier Wahl?" in Karl Schmid (Ed.) Reich und Kirche vor dem Investiturstreit, Sigmaringen 1985.

- Eduard Hlawitschka. ""Merkst Du nicht, daß Dir das vierte Rad am Wagen fehlt?" Zur Thronkandidatur Ekkehards von Meißen (1002) nach Thietmar, Chronicon IV c. 52," in Karl Hauck und Hubert Mordeck (Edd.) Geschichtsschreibung und geistiges Leben im Mittelalter. Festschrift für Heinz Löwe zum 65. Geburtstag, Köln/Wien 1978.

- Eduard Hlawitschka. Untersuchungen zu den Thronwechseln der ersten Hälfte des 11. Jahrhunderts und zur Adelsgeschichte Süddeutschlands. Zugleich klärende Forschungen um "Kuno von Öhningen", Sigmaringen 1987.

- Helmut Beumann. Die Ottonen, 5th Edition, Kohlhammer Verlag, Stuttgart etc. 2000, ISBN 3-17-013190-7.