Bernward of Hildesheim

Saint Bernward (c. 960 – 20 November 1022) was the thirteenth Bishop of Hildesheim from 993 until his death in 1022.[1]

Saint Bernward of Hildesheim | |

|---|---|

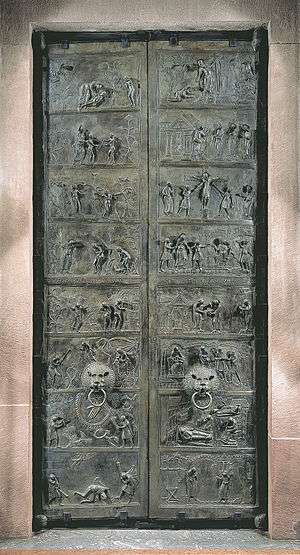

Bernward's doors at St. Mary's Cathedral | |

| Born | 960 Duchy of Saxony |

| Died | 20 November 1022 |

| Venerated in | Roman Catholic Church Eastern Orthodox Church |

| Major shrine | St. Michaels's Cathedral, Hildesheim |

| Feast | 20 November |

| Attributes | Bishop vestments, small cross, hammer, chalice |

| Patronage | Architects, painters, sculptors, goldsmiths |

Life

Bernward came from a Saxon noble family. His grandfather was Athelbero, Count Palatine of Saxony. Having lost his parents at an early age, he came under the care of his uncle Volkmar, Bishop of Utrecht, who entrusted his education to Thangmar, learned director of the cathedral school at Heidelberg. Under this master, Bernward made rapid progress in the sciences and in the liberal and even mechanical arts. He became very proficient in mathematics, painting, architecture, and particularly in the manufacture of ecclesiastical vessels and ornaments of silver and gold. He completed his studies at Mainz, where he was ordained priest by Archbishop Willigis, Chancellor of the Empire (975-1011). He declined a valuable preferment in the diocese of his uncle, Bishop Volkmar, and chose to remain with his grandfather, Athelbero, to comfort him in his old age. Upon the death of the latter, in 987, he became chaplain at the imperial court, and was shortly afterwards appointed by the Empress-Regent Theophano, tutor to her son Otto III, then six years of age.[1]

His time in office fell during the era of the Saxon emperors, who had their roots in the area around Hildesheim and were personally related to Bernward. During this time, Hildesheim was a center of power in the Holy Roman Empire and Bernward was determined to give his city an image fitting for one of its stature. The column he planned on the model of Trajan's Column at Rome never came to fruition, but Bernward revived classical precedent by having his name stamped on roof tiles made under his direction.[2] Bernward built up the cathedral district with a strong twelve-towered wall and erected further forts in the countryside to protect against attacks by the neighboring Slavic peoples. Under his direction arose numerous churches and other edifices, including even fortifications for the defence of his episcopal city against the invasions of the pagan Normans.[1] He protected his diocese vigorously from the attacks of the Normans.[3]

His life was set down in writing by his mentor, Thangmar, in Vita Bernwardi. For at least part of this document, the authorship is certain, but other parts were probably added in the High Middle Ages. He died on 20 November 1022, a few weeks after the consecration of the magnificent church of St. Michael, which he had built. Bernward was canonized by Pope Celestine III on 8 January 1193. His feast day is November 20.

St. Bernward's Church in Hildesheim, a neo-romanesque church built 1905-07 and St. Bernward's Chapel in Klein Düngen which dates from the 13th century, are named after him.

World Heritage Sites

One of the most famous examples of Bernward's work is a monumental set of cast bronze doors known as the Bernward doors, now installed at St. Mary's Cathedral, which are sculpted with scenes of the Fall of Man (Adam and Eve) and the Salvation of Man (Life of Christ), and which are related in some ways to the wooden doors of Santa Sabina in Rome. Bernward was instrumental in the construction of the early Romanesque Michaelskirche. St. Michael's Church was completed after Bernward's death, and he is buried in the western crypt. These projects of Bernward's are today UNESCO World Heritage Sites.

St Michael's Church has exerted great influence on developments in architecture. The complex bears exceptional testimony to a civilization that has disappeared. These two edifices and their artistic treasures give a better overall and more immediate understanding than any other decoration in Romanesque churches in the Christian West. St Michael's Church was built between 1010 and 1020 on a symmetrical plan with two apses that was characteristic of Ottonian Romanesque art in Old Saxony. Its interior, in particular the wooden ceiling and painted stucco-work, its famous bronze doors and the Bernward bronze column, are – together with the treasures of St Mary's Cathedral – of exceptional interest as examples of the Romanesque churches of the Holy Roman Empire.

St Mary's Cathedral, rebuilt after the fire of 1046, still retains its original crypt. The nave arrangement, with the familiar alternation of two consecutive columns for every pillar, was modelled after that of St Michael's, but its proportions are more slender.[4]

See also

Notes

- Birkhaeuser, Jodoc Adolphe. "St. Bernward." The Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 2. New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1907. 4 Jan. 2013

- W. Oakeshott, Classical Inspiration in Medieval Art 1959:67, noted in Roberto Weiss, The Renaissance Discovery of Classical Antiquity (Oxford: Blackwell) 1973:4.

- Jackson D.D., L.L.D, Samuel Macauley ed.,"Bernward" in the New Schaff-Herzog Encyclopedia of Religious Knowledge, Funk and Wagnalls Company, New York, (1908)

- St. Mary's Cathedral and St. Michael's Church at Hildesheim, UNESCO

Sources

- Martina Giese: Die Textfassungen der Lebensbeschreibung Bischof Bernwards von Hildesheim (= Monumenta Germaniae Historica. Studien und Texte; Bd. 40) Hahnsche Buchhandlung, Hannover 2006, ISBN 978-3-7752-5700-8 (Recension)

- Bernward von Hildesheim (in German)

- Hans Jakob Schuffels in Brandt/Eggebrecht (Hrsg.): Bernward von Hildesheim und das Zeitalter der Ottonen, Katalog der Ausstellung 1993 Volume 1, p.31; Illustration of the document in Volume 2, p.453 (in German)

- History of Burgstemmen (in German)

- Bernhard Gallistl: Bernward of Hildesheim: a Case of Self-Planned Sainthood?', in The Invention of Saintliness, ed. by A. Mulder-Bakker. London 1992. pp. 145–162. ISBN 9780415267595

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Bernward of Hildesheim. |

- Ottonian Art, St. Michael's Church, Hildesheim (1001-1031), Smarthistory

- German Exhibition "Bernwards Schätze" (Bernward's Treasures) online Hannoverische Allgemeine photo gallery