Ḍād

Ḍād (ﺽ), is one of the six letters the Arabic alphabet added to the twenty-two inherited from the Phoenician alphabet (the others being ṯāʾ, ḫāʾ, ḏāl, ẓāʾ, ġayn). In name and shape, it is a variant of ṣād. Its numerical value is 800 (see Abjad numerals).

In Modern Standard Arabic and many dialects, it represents an "emphatic" /d/, and it might be pronounced as a pharyngealized voiced alveolar stop ![]()

![]()

| Position in word: | Isolated | Final | Medial | Initial |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glyph form: (Help) |

ض | ـض | ـضـ | ضـ |

Origin

Based on ancient descriptions of this sound, it is clear that in Qur'anic Arabic ḍ was some sort of unusual lateral sound.[1][2][4][5][6] Sibawayh, author of the first book on Arabic grammar, explained the letter as being articulated from "between the first part of the side of the tongue and the adjoining molars". It is reconstructed by modern linguists as having been either a pharyngealized voiced alveolar lateral fricative ![]()

This is an extremely unusual sound, and led the early Arabic grammarians to describe Arabic as the لغة الضاد lughat aḍ-ḍād "the language of the ḍād", since the sound was thought to be unique to Arabic.[1]

The emphatic lateral nature of this sound is possibly inherited from Proto-Semitic, and is compared to a phoneme in South Semitic languages such as Mehri (where it is usually an ejective lateral fricative).

The corresponding letter in the South Arabian alphabet is

The reconstruction of Proto-Semitic phonology includes an emphatic voiceless alveolar lateral fricative [ɬʼ] or affricate [t͡ɬʼ] for ṣ́. This sound is considered to be the direct ancestor of Arabic ḍād, while merging with ṣād in most other Semitic languages.

The letter itself is distinguished a derivation, by addition of a diacritic dot, from ص ṣād (representing /sˤ/).

Pronunciation

The standard pronunciation of this letter in modern Standard Arabic is the "emphatic" /d/: pharyngealized voiced alveolar stop ![]()

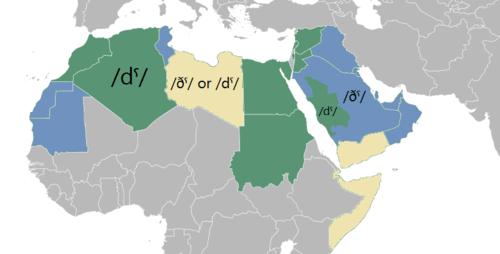

In most Bedouin influenced Arabic vernaculars ض ḍād and ظ ẓāʾ have been merged quite early[2] like in the varieties (such as Bedouin and Iraqi), where the dental fricatives are preserved, both the letters are pronounced /ðˤ/.[2][4][6] However, there are dialects in South Arabia and in Mauritania where both the letters are kept different but not in all contexts.[2] In other vernaculars such as Egyptian the distinction between ض ḍād and ظ ẓāʾ is most of the time made; but Classical Arabic ẓāʾ often becomes /zˤ/, e.g. ʿaẓīm (< Classical عظيم ʿaḏ̣īm) "great".[2][4][8]

"De-emphaticized" pronunciation of the both letters in the form of the plain /z/ entered into other non-Arabic languages such as Persian, Urdu, Turkish.[2] However, there do exist Arabic borrowings into Ibero-Romance languages as well as Hausa and Malay, where ḍād and ẓāʾ are differentiated.[2]

Transliteration

ض is transliterated as ḍ (D with underdot) in romanization. The combination ⟨dh⟩ is also sometimes used colloquially. In varieties where the Ḍād has merged with the Ẓāʾ, the symbol for the latter might be used for both (eg. ⟨ظل⟩ 'to stay' and ⟨ضل⟩ 'to be lost' may both be transcribed as ḏ̣al in Gulf Arabic).

When transliterating Arabic in the Hebrew alphabet, it is either written as ד (the letter for /d/) or as צ׳ (tsadi with geresh), which is also used to represent the /tʃ/ sound.

Unicode

| Preview | ض | |

|---|---|---|

| Unicode name | ARABIC LETTER DAD | |

| Encodings | decimal | hex |

| Unicode | 1590 | U+0636 |

| UTF-8 | 216 182 | D8 B6 |

| Numeric character reference | ض | ض |

See also

References

- Versteegh, Kees (2003) [1997]. The Arabic language (Repr. ed.). Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. p. 89. ISBN 9780748614363.

- Versteegh, Kees (1999). "Loanwords from Arabic and the merger of ḍ/ḏ̣". In Arazi, Albert; Sadan, Joseph; Wasserstein, David J. (eds.). Compilation and Creation in Adab and Luġa: Studies in Memory of Naphtali Kinberg (1948–1997). pp. 273–286.

- Alqahtani, Khairiah (June 2015). "A sociolinguistic study of the Tihami Qahtani dialect in Asir, Southern Arabia" (PDF). A sociolinguistic study of the Tihami Qahtani dialect in Asir, Southern Arabia: 45, 46.

- Versteegh, Kees (2000). "Treatise on the pronunciation of the ḍād". In Kinberg, Leah; Versteegh, Kees (eds.). Studies in the Linguistic Structure of Classical Arabic. Brill. pp. 197–199. ISBN 9004117652.

- Ferguson, Charles (1959). "The Arabic koine". Language. 35 (4): 630. doi:10.2307/410601.

- Ferguson, Charles Albert (1997) [1959]. "The Arabic koine". In Belnap, R. Kirk; Haeri, Niloofar (eds.). Structuralist studies in Arabic linguistics: Charles A. Ferguson's papers, 1954–1994. Brill. pp. 67–68. ISBN 9004105115.

- Roman, André (1983). Étude de la phonologie et de la morphologie de la koiné arabe. 1. Aix-en-Provence: Université de Provence. pp. 162–206.

- Retsö, Jan (2012). "Classical Arabic". In Weninger, Stefan (ed.). The Semitic Languages: An International Handbook. Walter de Gruyter. pp. 785–786. ISBN 978-3-11-025158-6.