Rupee

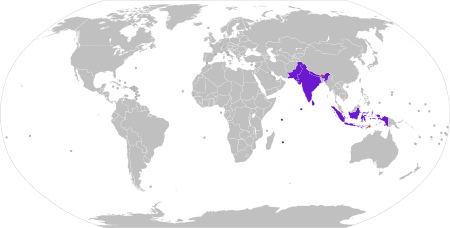

Rupee is the common name for the currencies of India, Indonesia, the Maldives, Mauritius, Nepal, Pakistan, Seychelles, and Sri Lanka, and of former currencies of Afghanistan, all Arab states of the Persian Gulf (as the Gulf rupee), British East Africa, Burma, German East Africa, the Trucial States, and Tibet. In Indonesia and the Maldives the unit of currency is known as rupiah and rufiyaa respectively.

India, Indonesia, Maldives, Mauritius, Nepal, Pakistan, Seychelles, Sri Lanka

Orange: Countries where a foreign country's rupee is legal tender

Indian rupee: Bhutan, Nepal, Zimbabwe

Indonesian rupiah: East Timor

The Indian rupees (₹) and Pakistani rupees (₨) are subdivided into one hundred paise (singular paisa) or pice. The Mauritian, Seychellois, and Sri Lankan rupees subdivide into 100 cents. The Nepalese rupee subdivides into one hundred paisa (singular and plural) or four Sukaas.

Etymology

The immediate precursor of the Rupee is the Rūpiya—the silver coin weighing 178 grains (11.53 grams) minted in northern India by first Sher Shah Suri during his brief rule between 1540 and 1545 and adopted and standardized later by the Mughal Empire. The weight remained unchanged well beyond the end of the Mughals till the 20th century.[1]

The Hindi-Urdu word rupyā is derived from the Sanskrit word rūpya, which means "wrought silver, a coin of silver",[2] in origin an adjective meaning "shapely", with a more specific meaning of "stamped, impressed", whence "coin". It is derived from the noun rūpa "shape, likeness, image". The word rūpa is further identified as related to the Dravidian root uruppu, which means "a member of the body".[3] Also, the word rūpam is rooted in Tamil as uru (shape) derived from ur (form) which itself is rooted in ul meaning "appear".[4]

History

The history of the rupee traces back to Ancient India circa 3rd century BC. Ancient India was one of the earliest issuers of coins in the world,[5] along with the Lydian staters, several other Middle Eastern coinages and the Chinese wen. The term is from rūpya, a Sanskrit term for silver coin,[6] from Sanskrit rūpa, beautiful form.[7]

Arthashastra, written by Chanakya, prime minister to the first Maurya emperor Chandragupta Maurya (c. 340–290 BCE), mentions silver coins as rūpyarūpa, other types including gold coins (suvarṇarūpa), copper coins (tāmrarūpa) and lead coins (sīsarūpa) are mentioned. Rūpa means form or shape, example, rūpyarūpa, rūpya – wrought silver, rūpa – form.[8]

In the intermediate times there was no fixed monetary system as reported by the Da Tang Xi Yu Ji.[9]

Sher Shah Suri (1540–1545), re-introduced the silver coin rupiya, weighing 178 grains. Its use was continued by the Mughal rulers.[10] Suri also introduced copper coins called dam and gold coins called mohur that weighed 169 grains (10.95 g).[11]

Until the middle of the 20th century, Tibet's official currency was also known as the Tibetan rupee.[12]

Early 19th-century East India Company rupees were used in Australia for a limited period.

The Indian rupee was the official currency of Dubai and Qatar until 1959, when India created a new Gulf rupee (also known as the "external rupee") to hinder the smuggling of gold.[13] The Gulf rupee was legal tender until 1966, when India significantly devalued the Indian rupee and a new Qatar-Dubai riyal was established to provide economic stability.[13]

East African Coast and South Arabia

In East Africa, Arabia, and Mesopotamia, the rupee and its subsidiary coinage was current at various times. The usage of the rupee in East Africa extended from Somalia in the north to as far south as Natal. In Mozambique, the British India rupees were overstamped, and in Kenya, the British East Africa Company minted the rupee and its fractions, as well as pice.

The rise in the price of silver immediately after the First World War caused the rupee to rise in value to two shillings sterling. In 1920 in British East Africa, the opportunity was then taken to introduce a new florin coin, hence bringing the currency into line with sterling. Shortly after that, the florin was split into two East African shillings. This assimilation to sterling did not, however, happen in British India itself. In Somalia, the Italian colonial authority minted 'rupia' to exactly the same standard and called the pice 'besa'.

Straits Settlements

The Straits Settlements were originally an outlier of the British East India Company. The Spanish dollar had already taken hold in the Straits Settlements by the time the British arrived in the 19th century. The East India Company tried to introduce the rupee in its place. These attempts were resisted by the locals, and by 1867 when the British government took over direct control of the Straits Settlements from the East India Company, attempts to introduce the rupee were finally abandoned.

Denominations

Formerly, the rupee (11.66 g, .917 fine silver) was divided into 16 annas, 64 paise, or 192 pies. Each circulating coin of British India, until the rupee was decimalised, had a different name in practice. A paisa was equal to two dhelas, three pies, or six damaris. Other coins for half anna (adhanni, or two paisas), two annas (duanni), four annas (a chawanni, or a quarter of a rupee), and eight annas (an athanni, or half a rupee) were widely in use until decimalization in 1961. (The numbers adha, do, chār, ātha mean respectively half, two, four, eight in Hindi and Urdu.[14]) Two paisa was also called a taka, see below.

In India presently (from 2010 onwards), the 50 paise coin (half a rupee) is the lowest valued legal tender. Coins of 1, 2, 5, and 10 rupees and banknotes of 5, 10, 20, 50, 100, 200, 500, and 2000 rupees are commonly in use for cash transaction.

Decimalisation occurred in Ceylon (Sri Lanka) in 1969, in India in 1957, and in Pakistan in 1961. Since 1957 an Indian rupee is divided into 100 paise. The decimalized paisa was originally officially named naya paisa meaning the "new paisa" to distinguish it from the erstwhile paisa which had a higher value of 1⁄64 rupee. The word naya was dropped in 1964 and since then it is simply known as paisa (plural paise). The issuance of the Indian currency is controlled by the Reserve Bank of India, whereas in Pakistan it is controlled by State Bank of Pakistan. The most commonly used symbol for the rupee is "Rs". India adopted a new symbol (₹) for the Indian rupee on 15 July 2010.

In most parts of India, the rupee is known as rupaya, rupaye, or one of several other terms derived from the Sanskrit rūpya, meaning silver.

Ṭaṅka is an ancient Sanskrit word for money. While the two-paise coin was called a taka in West Pakistan, the word taka was commonly used in East Pakistan (now Bangladesh), alternatively for rupee. In the Bengali and Assamese languages, spoken in Assam, Tripura, and West Bengal, the rupee is known as a taka, and is written as such on Indian banknotes. In Odisha it is known as tanka. After its independence, Bangladesh started to officially call its currency "taka" (BDT) in 1971.

Large denominations of rupees are often counted in lac/lakh (100,000 = 1 lac/lakh, 100 lac/lakh = 1 crore/karor, 100 crore/karor = 1 arab, 100 arab = 1 kharab/khrab, 100 kharab/khrab = 1 nil/neel, 100 nil/neel = 1 padma, 100 padma = 1 shankh, 100 shankh = 1 udpadha, 100 udpadha = 1 ank). Terms beyond a crore are not generally used in the context of money, e.g. an amount would be called Rs 1 lakh crore (equivalent to 1 trillion) instead of Rs 10 kharab.

Symbol

The rupee sign “₨” is a currency sign used to represent the monetary unit of account in Pakistan, Sri Lanka, Nepal, Mauritius, Seychelles, and formerly in India. It resembles, and is often written as, the Latin character sequence “Rs” or “Rs.”. Currency signs exist for other countries that use the rupee but not this sign: their usage is also described at the main article.

Abbreviation

In latin script, "rupee" (singular) is abbreviated as Re. and "rupees" (plural) as Rs. The Indonesian rupiah is abbreviated Rp. In 19th century typography, abbreviations are often superscripted: or . In Brahmic scripts, rupee is often abbreviated with the grapheme for the first syllable, optionally followed by a circular abbreviation mark or a latin abbreviation point: रु૰ (Devanagari ru.),[15][16] રૂ૰ (Gujarati ru.),[16] රු (Sinhala ru), రూ (Telugu rū).

| Language | Word | Transliteration | Abbrev. | Unicode |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Malayalam | രൂപാ | rūpāa | രൂ | ( U+0D30 ര MALAYALAM LETTER RA ) + ( U+0D42 ൂ MALAYALAM VOWEL SIGN UU ) |

| Tamil | ரூபாய் | rūpāy | ரூ | ( U+0BB0 ர TAMIL LETTER RA ) + ( U+0BC2 ூ TAMIL VOWEL SIGN UU ) |

| Telugu | రూపాయి | rūpāyi | రూ | ( U+0C30 ర TELUGU LETTER RA ) + ( U+0C42 ూ TELUGU VOWEL SIGN UU ) |

| Sinhala | රුපියල | rupiyala | රු | (U+0DBB ර SINHALA LETTER RAYANNA) + (U+0DD4 ු SINHALA VOWEL SIGN KETTI PAA-PILLA) |

| Gujarati | રૂપિચો, રૂપિયા | rūpiyo, rūpiyā | રૂ૰ | U+0AB0 ર + U+0AC2 ૂ + U+0AF0 ૰ |

| Kannada | ರೂಪಾಯಿ | rūpāyi | ರ | U+0CB0 ರ KANNADA LETTER RA |

Value

The history of the rupees can be traced back to Ancient India around the 6th century BC. Ancient India had some of the earliest coins in the world,[5] along with the Chinese wen and Lydian staters. The rupee coin has been used since then, even during British India, when it contained 11.66 g (1 tola) of 91.7% silver with an ASW of 0.3437 of a troy ounce[17] (that is, silver worth about US$10 at modern prices).[18] At the end of the 19th century, the Indian silver rupee went onto a gold exchange standard at a fixed rate of one rupee to one shilling and fourpence in British currency, i.e. 15 rupees to 1 pound sterling.

Valuation of the rupee based on its silver content had severe consequences in the 19th century, when the strongest economies in the world were on the gold standard. The discovery of vast quantities of silver in the United States and various European colonies resulted in a decline in the value of silver relative to gold.

| Country | Currency | Symbol | ISO 4217 code |

Value to US dollar (As of 31 March 2020) |

Established | Preceding currency |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Indian rupee | ₹ | INR | ₹75.38 | 1540 | ||

| Indonesian rupiah | Rp | IDR | Rp 16,255.00 | 1949 | Netherlands Indies gulden | |

| Maldivian rufiyaa | Rf, MRf, MVR, .ރ or /- | MVR | Rf 15.41 | 1945 | Ceylonese rupee | |

| Mauritian rupee | ₨, रु | MUR | ₨ 39.25 | 1876 | Indian rupee, pound sterling, Mauritian dollar | |

| Nepalese rupee | रू | NPR | रू120.85 | 1932 | Nepalese mohar | |

| Pakistani rupee | ₨ | PKR | ₨ 166.50 | 1947 | Indian rupee (prior to partition) | |

| Seychellois rupee | SR, SRe | SCR | SR 13.74 | 1976 | Mauritian rupee | |

| Sri Lankan rupee | ₨, රු, ரூ | LKR | ₨ 189.54 | 1885 | Indian rupee, pound sterling, Ceylonese rixdollar |

See also

- Indonesian rupiah

- Maldivian rufiyaa

- Coins of British India

- Rupee (The Legend of Zelda), a fictional currency

- The Revised Standard Reference Guide to Indian Paper Money

References

- Mughal Coinage at Reserve Bank of India Monetary Museum. Retrieved 1 Dec 2019.

- "Etymology of rupee". etymonline.com. 20 September 2008. Retrieved 20 September 2008.

- Robert Caldwell. A Comparative Grammar of the Dravidian or South-Indian family of languages. ISBN 9781113662552.

Tamil noun uruppu, a member of the body, the body itself, a form – e.g., the sign of a case is called the uruppu of the case. Dr. Gundert does not doubt that the Sanskrit rūpa is derived from this Dravidian uruppu, even though uruppu may be a tadbhava of rūpa.

- Devaneya Pavanar (January 2002). A Comprehensive Etymological Dictionary of the Tamil Language. Directorate of Tamil Etymological Dictionary Project,Government of Tamil Nadu (India), W-605, Anna Nagar Western Extension, Madras 600 101. p. உ.94.

- Subodh Kapoor (January 2002). The Indian encyclopaedia: biographical, historical, religious ..., Volume 6. Cosmo Publications. p. 1599. ISBN 81-7755-257-0.

- Turner, Sir Ralph Lilley (1985) [London: Oxford University Press, 1962–1966.]. "A Comparative Dictionary of the Indo-Aryan Languages". Includes three supplements, published 1969–1985. Digital South Asia Library, a project of the Center for Research Libraries and the University of Chicago. Retrieved 26 August 2010.

rū'pya 10805 rū'pya 'beautiful, bearing a stamp' ; 'silver'

- Turner, Sir Ralph Lilley (1985) [London: Oxford University Press, 1962–1966.]. "A Comparative Dictionary of the Indo-Aryan Languages". Includes three supplements, published 1969–1985. Digital South Asia Library, a project of the Center for Research Libraries and the University of Chicago. Retrieved 26 August 2010.

rūpa 10803 'form, beauty'

- Redy. "AIndia.htm". Worldcoincatalog.com. Retrieved 20 June 2013.

- Trübner’s Oriental Series DA TANG XIYU JI Great Tang Dynasty Records of the Western World, translated by Samuel Beal TWO VOLUMES Kegan, Paul, Trench, Teubner & Co. London • 1906 [First Edition ‐ London • 1884]

- "Mughal Coinage". Archived from the original on 5 October 2002.

Sher Shah issued a coin of silver which was termed the Rupiya. This weighed 178 grains and was the precursor of the modern rupee. It remained largely unchanged till the early 20th Century

- Mughal Coinage Archived 16 May 2008 at the Wayback Machine at RBI Monetary Museum. Retrieved 4 May 2008.

- Theodore Roosevelt; Kermit Roosevelt (1929). "Trailing the giant panda". Nature. Scribner. 124 (3138): 944. Bibcode:1929Natur.124R.944.. doi:10.1038/124944b0.

... The currency in general use was what was known at the Tibetan rupee ...

- Richard F. Nyrop (2008). Area Handbook for the Persian Gulf States. Wildside Press. ISBN 978-1-4344-6210-7.

... The Indian rupee was the principal currency until 1959, when it was replaced by a special gulf rupee to halt gold smuggling into India ...

- See, for example https://www.hindi.co/ginatee/numbers_saNkhyaaENn.html, https://omniglot.com/language/numbers/urdu.htm

- Deka, Rabin (25 January 2010). "Additions to Deva-Nagariscript and Bengali script" (PDF). This proposal contains two atteststions with a solid dot instead of a circle. Deka also points out that रु. is printed with a shorter head bar when used as the abbreviation for rupee.

- Pandey, Anshuman (7 October 2009). "L2/09-331 Proposal to Deprecate Gujarati Rupee Sign" (PDF). Retrieved 25 October 2019.

- Krause, Chester L.; Clifford Mishler (2004). Standard Catalog of World Coins: 1801–1900. Colin R. Bruce II (senior editor) (4th ed.). Krause Publications. ISBN 0873497988.

- "Equivalent of 0.343762855 troy ounce of silver in U.S. dollar". xe.com. 2 October 2006. Retrieved 2 October 2006.

Sources and external links

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.