Tirana

Tirana (/tɪˈrɑːnə/ (![]()

Tirana | |

|---|---|

Clockwise from top: The Skanderbeg Square, Kapllan Pasha Tomb, Grand Mosque, Ministry of Internal Affairs, Grand Park, Petrelë Castle, Resurrection Orthodox Cathedral and Toptani Center. | |

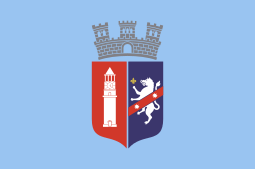

Flag  Seal | |

Tirana  Tirana | |

| Coordinates: 41°19′44″N 19°49′04″E | |

| Country | Albania |

| Region | Central Albania |

| County | Tirana |

| Settled | 1614 |

| Government | |

| • Type | Government |

| • Mayor | Erion Veliaj (Socialist Party) |

| • Council Chairman | Aldrin Dalipi |

| Area | |

| • Municipality | 1,110.03 km2 (428.58 sq mi) |

| • Urban | 41.8 km2 (16.1 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 110 m (360 ft) |

| Population (2011) | |

| • Density | 502/km2 (1,300/sq mi) |

| • Municipality | 557,422[1] |

| • Metro | 906,166[2] |

| Demonym(s) | Tiranas (m) Tiranase (f) Tirons (m) Tironse (f) (local dialect) |

| Time zone | UTC+1 (CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+2 (CEST) |

| Postal code | 1001–1028, 1031 |

| Area code(s) | 04 |

| Vehicle registration | TR |

| HDI (2018) | 0.818[3] – very high · 1st |

| Website | tirana.al |

Tirana flourished as a city in 1614 but the region that today corresponds to the city's territory has been continuously inhabited since the Iron Age. The area was inhabited by Illyrians, and was most likely the core of the Illyrian Kingdom of the Taulantii, which in Classical Antiquity was centered in the hinterland of Epidamnus. Following the Illyrian Wars it was annexed by Rome and became an integral part of the Roman Empire. The heritage of that period is still evident and represented by the Mosaics of Tirana. Later, in the 5th and 6th centuries, a Early Christian basilica was built around this site.

After the Roman Empire split into East and West in the 4th century, its successor the Byzantine Empire took control over most of Albania, and built the Petrelë Castle in the reign of Justinian I. The city was fairly unimportant until the 20th century, when the Congress of Lushnjë proclaimed it as Albania's capital, after the Albanian Declaration of Independence in 1912.

Tirana is the most important economic, financial, political and trade center in Albania due to its significant location in the center of the country and its modern air, maritime, rail and road transportation. It is the seat of power of the Government of Albania, with the official residences of the President and Prime Minister of Albania, and the Parliament of Albania. The city was awarded the title of the European Youth Capital of 2022.[6]

Geography

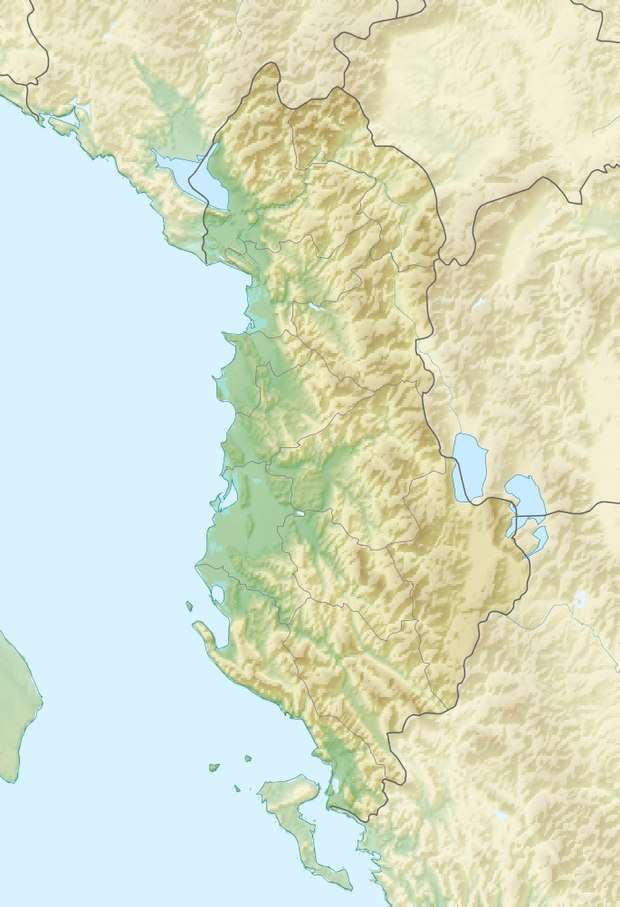

.jpg)

Tirana extends at the Plain of Tirana in the center of Albania between the mount of Dajti in the east, the hills of Kërrabe, Sauk and Vaqarr in the south, and a valley to the north overlooking the Adriatic Sea. The average altitude is about 110 meters (360 ft) above sea level, with a maximum of 1,828 metres (5,997 feet) at Maja Mincekut of Mali me Gropa in Shenmeri.[7]

The city is 501 kilometres (311 miles) north of Athens, 613 kilometres (381 miles) southeast of Rome, 131 kilometres (81 miles) south of Podgorica in Montenegro, 153 kilometres (95 miles) southwest of Skopje in North Macedonia and 250 kilometres (160 miles) from Pristina in Kosovo.

The city is surrounded by two important protected areas: the Dajti National Park and Mali me Gropa-Bizë-Martanesh Protected Landscape. In winter, the mountains are often covered with snow and are a popular retreat for the population of Tirana, which rarely receives snowfalls. In terms of biodiversity, the forests are mainly composed of pine, oak and beech, while its interior relief is dotted with canyons, waterfalls, caves, lakes and other landforms.[8] Thanks to its natural heritage, it is considered the "Natural Balcony of Tirana". The mountain can be reached by a narrow asphalt mountain road onto an area known as Fusha e Dajtit. From this small area there is an excellent view of Tirana and its plain.

Tiranë river flows through the city, as does the Lanë river. Tirana is home to several artificial lakes, including Tirana, Farka, Tufina, and Kashar. The present municipality was formed in the 2015 local government reform by the merger of the former municipalities of Baldushk, Bërzhitë, Dajt, Farkë, Kashar, Krrabë, Ndroq, Petrelë, Pezë, Shëngjergj, Tirana, Vaqarr, Zall-Bastar and Zall-Herr, which became municipal units. The seat of the municipality is the city of Tirana.[9]

Climate

The city is defined by the Köppen climate classification as Cfa, in other words the city has a humid subtropical climate and receives a commensurably amount of precipitation, during summer, to avoid the mediterranean climate (Csa) classification, since every summer month receives more than 40 millimetres (1.6 in) of rainfall, with hot and moderately dry summers and cool and wet winters. It lies on the boundary between Zone 7 and Zone 9 in terms of the hardiness zone.[11]

The average precipitation is about 1,266 millimetres (49.8 inches) per year. The city receives the majority of precipitation in winter months, which occurs from November to March, and less in summer months from June to September. In terms of precipitation, both rain and snow, the city is ranked among the wettest cities in the European Continent.[5]

Temperatures vary throughout the year from an average of 6.7 °C (44.1 °F) in January to 24 °C (75 °F) in July. Springs and summers are very warm to hot often reaching over 20 °C (68 °F) from May to September. During autumn and winter, from November to March, the average temperature drops and is not lower than 6.7 °C (44.1 °F). The city receives approximately 2500 hours of sun.[12]

| Climate data for Tirana (Tirana 7), elevation: 90 m or 300 ft, 1961-1990 normals, extremes 1940-present[lower-alpha 1] | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 21.3 (70.3) |

28.0 (82.4) |

30.3 (86.5) |

32.6 (90.7) |

35.9 (96.6) |

39.7 (103.5) |

42.2 (108.0) |

41.4 (106.5) |

39.7 (103.5) |

36.1 (97.0) |

31.3 (88.3) |

22.5 (72.5) |

42.2 (108.0) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 11.6 (52.9) |

12.9 (55.2) |

15.6 (60.1) |

19.0 (66.2) |

23.8 (74.8) |

27.7 (81.9) |

30.7 (87.3) |

30.7 (87.3) |

27.3 (81.1) |

21.8 (71.2) |

17.1 (62.8) |

13.0 (55.4) |

21.0 (69.8) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 6.7 (44.1) |

7.8 (46.0) |

10.0 (50.0) |

13.4 (56.1) |

18.0 (64.4) |

21.6 (70.9) |

24.0 (75.2) |

23.8 (74.8) |

20.7 (69.3) |

16.0 (60.8) |

11.7 (53.1) |

8.1 (46.6) |

15.2 (59.4) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 1.8 (35.2) |

2.6 (36.7) |

4.5 (40.1) |

7.9 (46.2) |

12.1 (53.8) |

15.6 (60.1) |

17.2 (63.0) |

16.9 (62.4) |

14.1 (57.4) |

10.1 (50.2) |

6.3 (43.3) |

3.2 (37.8) |

9.4 (48.9) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −10.4 (13.3) |

−9.4 (15.1) |

−7.0 (19.4) |

−1.0 (30.2) |

2.5 (36.5) |

5.6 (42.1) |

4.2 (39.6) |

10.0 (50.0) |

3.8 (38.8) |

−1.3 (29.7) |

−4.3 (24.3) |

−6.9 (19.6) |

−10.4 (13.3) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 143 (5.6) |

132 (5.2) |

115 (4.5) |

104 (4.1) |

103 (4.1) |

68 (2.7) |

42 (1.7) |

46 (1.8) |

78 (3.1) |

114 (4.5) |

172 (6.8) |

148 (5.8) |

1,266 (49.8) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.1 mm) | 13 | 13 | 14 | 13 | 12 | 7 | 5 | 4 | 6 | 9 | 16 | 16 | 128 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 74 | 73 | 69 | 72 | 68 | 69 | 62 | 64 | 71 | 70 | 76 | 79 | 71 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 124 | 125 | 165 | 191 | 263 | 298 | 354 | 327 | 264 | 218 | 127 | 88 | 2,544 |

| Average ultraviolet index | 2 | 2 | 4 | 6 | 8 | 9 | 9 | 8 | 6 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 5 |

| Source: DWD,[13][14][note 1] Meteo Climat (record highs and lows),[15] NOAA (some records, rain and snow days)[16] and Weather Atlas[17] | |||||||||||||

- For rainy and snowy days the monthly values are not available, only annual.

Urbanism

In September 2015, Tirana organized its first vehicle-free day, joining forces with numerous cities across the globe to fight against the existing problem of urban air pollution. This initiative resulted in a considerable drop in both air and noise pollution, encouraging the Municipality to organize a vehicle-free day every month.

The city suffers from problems related to overpopulation,[18] such as waste management, high levels of air pollution and significant noise pollution. Over the last decades, air pollution has become a pressing concern as the number of cars has increased. These are mostly 1990s and early 2000s diesel cars,[19] while it is widely believed that the fuel used in Albania contains larger amounts of sulfur and lead than in the European Union. Effective 1 January 2019, the government has imposed an import ban of used vehicles made prior to 2005 in an effort to curb pollution, encourage the buying of new cars from certified domestic dealerships, and to improve overall road safety. Another source of pollution are PM10 and PM2.5 inhaled particulate matter and NO2 gases[20][21] resulting from rapid growth in the construction of new buildings and expanding road infrastructure.[22]

Untreated solid waste is present in the city and outskirts. Additionally, there have been complaints of excessive noise pollution. Despite the problems, the Grand Park at the Artificial Lake has some effect on absorbing CO2 emissions, while over 2.000 trees have been planted around sidewalks. Works for four new large parks have started in the summer of 2015 located in Kashar, Farkë, Vaqarr, and Dajt. These parks are part of the new urban plan striving to increase the concentration of green spaces in the capital.[23] The government has included designated green areas around Tirana as part of the Tirana Greenbelt where construction is not permitted or limited.[24][25]

History

Early development

The discovery of the Pellumbas Cave near Tirana shows that ancient human culture was present in Albania as early as the Paleolithic era.[26][27][28] The region that today corresponds to the city's territory has been continuously inhabited since the Iron Age. The area was inhabited by Illyrians, and was most likely the core of the Illyrian kingdom of the Taulantii, which in Classical antiquity was centered in the hinterland of Epidamnus.[29] The oldest discovery within the urban area of Tirana was a Roman house, which was transformed into an aisleless church with a mosaic floor, dating to the 3rd century, with other remains found near a medieval temple at Shengjin Fountain in the eastern suburbs. A castle possibly called Tirkan, whose remnants are found along Murat Toptani Street, was built by Byzantine Emperor Justinian I and restored by Ahmed Pasha Toptani in the 18th century.[30]

Tirana is mentioned in Venetian documents in 1418, one year after the Ottoman conquest of the area: "...the resident Pjeter, son of late Domenik from the village of Tirana...".[31] Records of the first land registrations under the Ottomans in 1431–32 show that Tirana consisted of 60 inhabited areas, with nearly 2,028 houses and 7,300 inhabitants. In 1510, Marin Barleti, an Albanian Catholic priest and scholar, in the biography of the Albanian national hero Skanderbeg, Historia de vita et gestis Scanderbegi Epirotarum principis (The story of life and deeds of Skanderbeg, the prince of Epirotes), referred to this area as a small village, distinguishing between "Little Tirana" and "Great Tirana".[31] It is later mentioned in 1572 as Borgo di Tirana.[32]

According to Hahn, the settlement had already started to develop as a bazaar and included several watermills,[33] even before 1614, when Sulejman Bargjini, a local ruler, built the Old Mosque, a small commercial centre, and a hammam (Turkish bath). This is confirmed by oral sources, which state that there were two earlier mosques 300–400 m from the Old Mosque, towards today's Ali Demi Street. The Mosque of Reç and the Mosque of Mujo were positioned on the left side of the Lana river and were older than the Old Mosque.[33] Later, the Et'hem Bey Mosque, built by Molla Bey of Petrela, was constructed. It employed the best artisans in the country and was completed in 1821 by Molla's son Etëhem, who was also Sulejman Bargjini's great-nephew.

In 1800, the first newcomers arrived in the settlement, the so-called ortodoksit. They were Vlachs from villages near Korçë and Pogradec, who settled around modern day Tirana Park on the Artificial Lake.[34] They started to be known as the llacifac and were the first Christians to arrive after the creation of the town. In 1807, Tirana became the center of the Subprefecture of Krujë-Tirana. After 1816, Tirana languished under the control of the Toptani family of Krujë. Later, Tirana became a sub-prefecture of the newly created Vilayet of Shkodër and the Sanjak of Durrës. In 1889, the Albanian language started to be taught in Tirana's schools, and the patriotic club Bashkimi was founded in 1908.

2.jpg)

Modern development

Capital of Albania

On 28 November 1912, the national flag was raised in agreement with President Ismail Qemali. During the Balkan Wars, the city was temporarily occupied by the Serbian army and it took part in uprising of the villages led by Haxhi Qamili. In August 1916, the first city map was compiled by the specialists of the Austro-Hungarian army.[35] Following the capture of the town of Debar by Serbia, many of its Albanian inhabitants fled to Turkey, the rest went to Tirana.[36] Of those that ended up in Istanbul, some of their number migrated to Albania, mainly to Tirana where the Dibran community formed an important segment of the city's population from 1920 onward and for some years thereafter.[36] On 8 February 1920, the Congress of Lushnjë proclaimed Tirana as the temporary capital of Albania, which had gained independence in 1912.[37] The city acquired that status permanently on 31 December 1925. In 1923, the first regulatory city plan was compiled by Austrian architects.[38] The centre of Tirana was the project of Florestano Di Fausto and Armando Brasini, well-known architects of the Mussolini period in Italy. Brasini laid the basis for the modern-day arrangement of the ministerial buildings in the city centre. The plan underwent revisions by Albanian architect Eshref Frashëri, Italian architect Castellani and Austrian architects Weiss and Kohler. The modern Albanian parliament building served as an officers' club. It was there that, in September 1928, Zog of Albania was crowned King Zog I, King of the Albanians.

Tirana was the venue for the signing of the Pact of Tirana between Fascist Italy and Albania. During the rule of King Zog a lot of Muhaxhirs emigrated towards Tirana, which lead to a growing population in the capital city in the early 20th century.[39]

In 1939, Tirana was captured by Fascist forces, who appointed a puppet government. In the meantime, Italian architect Gherardo Bosio was asked to elaborate on previous plans and introduce a new project in the area of present-day Mother Teresa Square.[40] A failed assassination attempt was made on Victor Emmanuel III of Italy by a local resistance activist during a visit to Tirana. In November 1941, two emissaries of the Communist Party of Yugoslavia (KPJ), Miladin Popović and Dušan Mugoša, called a meeting of three Albanian communist groups and founded the Communist Party of Albania, and Enver Hoxha soon emerged as its leader.

The town soon became the center of the Albanian communists, who mobilized locals against Italian fascists and later Nazi Germans, while spreading ideological propaganda. On 17 November 1944, the town was liberated after a fierce battle between the Communists and German forces. The Nazis eventually withdrew and the communists seized power.

Communist Albania

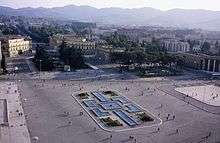

From 1944 to 1991, massive socialist-style apartment complexes and factories were built, while Skanderbeg Square was redesigned, with a number of buildings demolished. For instance, Tirana's former Old Bazaar and the Orthodox Cathedral were razed to the ground in order to build the Soviet-styled Palace of Culture. The northern portion of the main boulevard was renamed Stalin Boulevard and his statue was erected in the city square. Because private car ownership was banned, mass transportation consisted mainly of bicycles, trucks and buses. After Hoxha's death, a pyramidal museum was constructed in his memory by the government.

Before and after the proclamation of Albania's policy of self-imposed isolationism, a number of high-profile figures paid visits to the city, such as Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev, Chinese Premier Zhou Enlai and East German Foreign Minister Oskar Fischer. In 1985, Enver Hoxha's funeral was held in Tirana. A few years later, Mother Teresa became the first religious figure[41] to visit the country after the end of Albania's long anti-religious atheist stance. She paid respects to her mother and sister resting at a local cemetery.

.jpg)

Starting at the campus and ending at Skanderbeg Square with the toppling of Enver Hoxha's statue, the city saw significant demonstrations by University of Tirana students demanding political freedoms in the early 1990s. On the political aspect, the city witnessed a number of events. Personalities visited the capital, such as former U.S. Secretary of State James Baker and Pope John Paul II. The former visit came amidst the historical setting after the fall of communism, as hundreds of thousands were chanting in Skanderbeg Square Baker's famous saying of "Freedom works!".[42] Pope John Paul II became the first major religious leader to visit Tirana, though Mother Teresa had visited few years prior.

During the Balkans turmoil in the mid-1990s, the city experienced dramatic events such as the unfolding of the 1997 unrest in Albania and a failed coup d'état on 14 September 1998. In 1999, following the Kosovo War, Tirana Airport became a NATO airbase, serving its mission in the former Yugoslavia.

21st century

Starting in 2000, former Tirana mayor Edi Rama (mayor from 2000 to 2011) under the Ilir Meta government, undertook a campaign to demolish illegal buildings around the city centre and along the Lana River banks to bring the area to its pre-1990 state. In an attempt to widen roads, Rama authorized the bulldozing of private properties so that they could be paved over, thus widening streets. Most main roads underwent reconstruction, such the Ring Road (Unaza), Kavaja Street and the main boulevard. Rama led the initiative to paint the façades of Tirana's buildings in bright colours (known as Edi Rama colours – very bright pink, yellow, green, violet) although much of their interiors continued to degrade. Rama's critics claimed that he focused too much attention on cosmetic changes without fixing any of the major problems such as shortages of drinking water and electricity.[43][44] A richer calendar of events was introduced and a Municipal Police force established.

Since 2005 the southeast region of Tirana, mainly Farke and Petrela has had a burst becoming the preferred destination with many residence complexes being built and having the biggest mall in Albania, the Tirana East Gate (TEG).[45][46] In 2007, U.S. President George W. Bush marked the first time that such a high ranking American official visited Tirana.[47] A central Tirana street was named in his honor.

In 2008, the Gërdec explosions were felt in the capital as windows were shattered and citizens shaken. On 21 January 2011, Albanian police clashed with opposition supporters in front of the Government building as cars were set on fire, three persons killed and 150 wounded.[48]

Following the 2015 municipal elections, power was transferred from the Democratic Party representative Lulzim Basha, to the Socialist Party candidate Erion Veliaj.[50] The country underwent a territorial reform, in which defunct communes were merged with municipalities, leaving only 61 of them in total.[51] Thirteen of Tirana's former communes were integrated as administrative units joining the existing eleven.[52] Since then, Tirana is undergoing major changes in law enforcement and new projects, as well as continuing the ones started by Veliaj's predecessor. In their first few council meetings, 242 social houses got allocated to families in need.[53] Construction permits were suspended until the capital's development plan is revised and synthesized.[52] In addition the municipality will audit all permits granted in the previous years.

In 2016, Skanderbeg Square was redesigned according to an earlier plan brought forward in 2010. This included greater green space areas around the square, underground parking, and the introduction of stone material taken from all corners of Albania and Albanian-inhabited lands. Albania's rich flora were represented by the gardens around the square, while the former garden behind Skanderbeg's monument was restored to its pre-2010 state and named Europe Park. Once the project is completed, the square will serve as a venue for the annual Christmas Village of Festivities, music concerts, and where surrounding institutions would showcase themselves in an open environment concept such as in the yearly Nuit Blanche on 29 November.

The New Boulevard (Albanian: Bulevardi i Ri) was opened recently north of Zog I Boulevard at the defunct Tirana Rail Station, laying the foundation for the development of Tirana north of Skanderbeg Square and south of the Tirana River. The new headquarters of Tirana City Hall are planned to be built along the New Boulevard together with a central park located nearby.

The architect Stefano Boeri was contracted to work on the General Urban Plan of Tirana (TR030), which makes a series of interventions to the city's infrastructure. The plan was submitted for approval to the Municipality Council in November 2016.[54]

Demography

| Population growth of Tirana in selected periods | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | 1703 | 1820 | 1923 | 1937 | 1955 | 1989 | 2001 | 2012 |

| Pop. | 4,000 | 12,000 | 10,845 | 35,000 | 108,200 | 324,532 | 430,407 | 557,422 |

| ±% p.a. | — | +0.94% | −0.10% | +8.73% | +6.47% | +3.28% | +2.38% | +2.38% |

| Source: [55][56][57][58][59] | ||||||||

The Institute of Statistics (INSTAT) estimated the population of the municipality of Tirana at 418,495 in 2011.[60] With a population density of 502 people per square kilometre, Tirana is the most densely populated municipality in the country.[1] The encompassing metropolitan area, consisting of the regions of Durrës and Tirana, has a combined population of approximately 1 million amounting to nearly one third of the country's total population.[61]

Historically, Tirana has experienced a steady population increase in the past years, especially after the fall of ommunism in the late twentieth century as well as the beginnings of the twenty-first century. The remarkable growth was, and still is, largely fueled by migrants from all over the country often in search of employment and improved living conditions. Between 1820 and 1955, the population of Tirana tenfolded while during the period from 1989 to 2011, the city's population grew annually by approximately 2.7%. In the 19th and 20th centuries, the city had a rate of growth less than 1% annually until the 1973s, then down to less than 8% per year until the middle 20th century figures.[62]

Tirana's population is composed by a mixture of different cultural and ethnic groups from Southern Europe. The most represented ethnicities are Albanians (84.10%), Greeks (0.35%), Aromanians (0.11%), Macedonians (0.07%) and Italians (0.03%).[63]

Religion

In Albania, a secular state with no state religion, the freedom of belief, conscience and religion is explicitly guaranteed in the constitution of Albania.[65][66] Tirana is religiously diverse and has many places of worship catering to its religious population whom are adherents of Islam, Christianity and Judaism but also of Atheism and Agnosticism.

In the 2011 census, 55.7% of the population of the municipality of Tirana was counted as Muslim, 3.4% as Bektashis and 11.8% as Christian including 5.4% as Roman Catholic and 6.4% as Eastern Orthodox.[67] The remaining 29.1% of the population reported having no religion or did not provided an adequate answer. The census of 2011 did not included specific municipality level data for other religious groups. The Roman Catholic Church is represented in Tirana by the Archdiocese of Tiranë and Durrës, with the St Paul's Cathedral as the seat of the prelacy. The Albanian Orthodox community is served by the Archbishop of Tirana in the Resurrection Cathedral.

Politics

Tirana is the capital city of the Republic of Albania thus playing an essential role in shaping the political, economic and social life of the country.[68] The city houses government functions and government institutions for which the national government is responsible, as for instance the executive, juridical and legislative of Albania. The President and Prime Minister of Albania reside and work at the Presidenca and Kryeministria, respectively, while the Parliament of Albania houses at the Dëshmorët e Kombit Boulevard.[69][70][71]

Albania's highest courts maintains their headquarters in Tirana, including the Supreme Court, the Constitutional Court, the Court of Appeal and the Administrative Court. Tirana is also home to more than 45 embassies and representative bodies as an international political actor.[72]

Administration

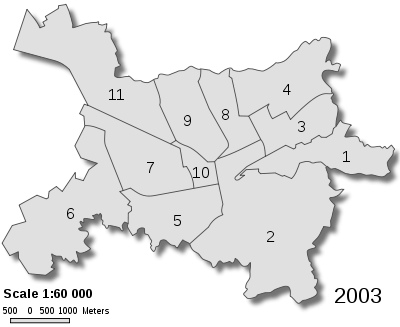

The Mayor of Tirana along with the Cabinet of Tirana exercises executive power. The Assembly of Tirana functions as the city parliament and consists of 55 members, serving four-year terms. It primarily deals with budget, global orientations and relations between the city and the Government of Albania. It has 14 committees and its Chairman is Aldrin Dalipi from the Socialist Party. Each of the members have a specific portfolio such as economy, finance, juridical, education, health care, and several professional services, agencies and institutes. The Municipality of Tirana is divided into 24 administrative units, with an own appointed mayor and council.[73]

In 2000, the centre of Tirana from the central campus of University of Tirana in the Mother Teresa Square up to the Skanderbeg Square, was declared the place of Cultural Assembly, and given state protection. The historical core of the capital lies around pedestrian only Murat Toptani Street, while the most prominent city district is Blloku. This neighborhood is the most popular part under the youth of Tirana. It is located in the southern side of Tirana and borders Kombinat and the center of the city. Until recently the city lacked a proper address system. In 2010, the municipality undertook the installing of street name signs and entrance numbers while every apartment entrance was physically stamped.[74]

International relations

List of twin towns of Tirana.[75] As Tirana, many of them are the most influential and largest or primate cities of their country and political, economical, cultural capital of their country.

Economy

Tirana is the heart of the economy of Albania and the most industrialised and economically fastest growing region in Albania. Of the main sectors, the tertiary sector is the most important for the economy of Tirana and employs more than 68% of work force of Tirana.[77] 26% of the working population makes up the secondary sector followed by the primary sector with only 5%.[77]

The city began to develop at the beginning of the 16th century as it was part of the Ottoman Empire, when a bazaar was established, and its craftsmen manufactured silk and cotton fabrics, leather, ceramics and iron, silver and gold artefacts.[78] In the 20th century, the city and its surrounding areas expanded rapidly and became the most heavily industrialised region of the country.

The most significant contribution is made by the tertiary sector which has developed considerably since the fall of communism in Albania. Forming the financial center of the country, the financial industry is a major component of the city's tertiary sector and remains in good conditions overall due to privatization and the commendable monetary policy.[79] All of the most important financial institutions, such as the Bank of Albania and the Albanian Stock Exchange are centred in Tirana as well as most of the banking companies such as the Banka Kombëtare Tregtare, Raiffeisen Bank, Credins Bank, Intesa Sanpaolo Bank and Tirana Bank.

The telecommunication industry represents another major and growing contributor to the sector.[80] A rapid development occurred as well as after the end of communism and decades of isolationism mainly due to the new national policy of reform and opening up sped up the industry's development. Vodafone, Telekom Albania and Eagle are the leading telecommunication providers in Tirana, as in all the country.

The tourism industry of the city has expanded in recent years to become a vital component of the economy.[81] Tirana has been officially dubbed as 'The Place Beyond Belief' by local authorities.[82] The increasing number of international arrivals at the Tirana International Airport and Port of Durrës from across Europe, Australia and Asia has rapidly grown the number of foreign visitors in the city.[83][84]

The largest hotels of the city are the Tirana International Hotel, Maritim Plaza Tirana both situated in the heart of the city near Scanderbeg Square, and the Hyatt-owned luxury Mak Hotel Tirana[85] located next to the Air Albania Stadium, where Mariott Tirana Hotel is also planned to open.[86] Other major hotels present in central Tirana include the Rogner Hotel, Hilton Garden Inn Tirana, Xheko Imperial Hotel, Best Western Premier Ark Hotel, and Mondial Hotel.

Infrastructure

Transport

Tirana is served by Nënë Tereza International Airport, which is simultaneously the premier air gateway to the country. The airport was officially named in honour of the Albanian Roman Catholic nun and missionary, Mother Teresa. It connects Tirana with many destinations in different countries across Europe, Africa and Asia. The airport carried more than 3.3 million passengers in 2019 and is also the principal hub for the country's flag carrier, Air Albania.[87]

The city's geographical location in the center of Albania has long established the city as an integral terminus for the national road transportation, thus connecting the city to all parts of Albania and the neighbouring countries.[88] The Rruga Shtetërore 1 (SH1) connects Tirana with Shkodër and Montenegro in the north, and constitutes an essential section of the proposed Adriatic–Ionian motorway. The Rruga Shtetërore 2 (SH2) continues in the west and provides direct connection to Durrës on the Adriatic Sea. The Rruga Shtetërore 3 (SH3) is being transformed to the Autostrada 3 (A3) and follows the ancient Via Egnatia. It significantly constitutes a major section of the Pan-European Corridor VIII and links the city with Elbasan, Korçë and Greece in the south. Tirana is further connected, through the Milot interchange in the northwest, with Kosovo following as part of the Autostrada 1 (A1).

During the communist regime in Albania, a plan for the construction of a ring road around Tirana arose in 1989s with no implementation until the 2010s.[89] It is of major importance, especially concerning the demographic growth of the metropolitan region of Tirana as well as the importance of the economy. Although, constructions for the nowadays completed southern section of the ring road started in 2011, however, the northern and eastern sections are still in the planning process.[90]

Rail lines of Hekurudha Shqiptare (HSH) connected Tirana with all of the major cities of Albania, including Durrës, Shkodër and Vlorë. In 2013, the Tirana Railway Station was closed and moved to Kashar by the government of Tirana in order to create space for the Bulevardi i Ri project.[91] The new Tirana Station will be constructed in Laprakë, which is projected to be a multifunctional terminal for rail, tram and bus transportation.[92][93] Furthermore, a new rail line from Tirana through Nënë Tereza International Airport to Durrës is planned to be constructed.[94][95]

In 2012, Tirana municipality published a report according to which a project on the construction of two tram lines was under evaluation. The tram lines would have a total length of 16.7 kilometres (10.4 miles). The public transport in Tirana is, for now, focused only in the city centre, so that the people living in the suburbs have fewer or no public transport connections. Under the plan, the two tram lines will intersect in the Skanderbeg Square. The public transport system in Tirana is ten bus lines served by 250 to 260 buses every day.

The development of the tram network will provide an easier access to the city centre and beyond to necessary facilities, such as leisure areas or jobs without using personal vehicles.[96] The city of Tirana is served by the Port of Durrës, one of the largest passenger port in the Adriatic Sea, 36 km (22 mi) distant from the city. Passenger ferries from Durrës sail to Croatia, Greece, Italy, Montenegro and Slovenia.

During the administration of mayor Erion Veliaj, the government of Tirana has significantly increased the creation and expansion of a cycling infrastructure in the city in order to reduce traffic congestion as well as to improve the sustainable transportation.[97][98][99] Ecovolis was launched in 2011 offering rental services for bicycles at different centrally located stations for a small fee.[100][101] The international bicycle sharing system, Mobike, launched its operations on 8 June 2018 by deploying 4000 bicycles in the city.[102][103]

Education

After the fall of communism in Albania, a reorganization plan was announced in 1990, that would extend the compulsory education program from eight to ten years. The following year, major economic and political crisis in Albania, and the ensuing breakdown of public order, plunged the school system into chaos. Widespread vandalism and extreme shortages of textbooks and supplies had a devastating effect on school operations, prompting Italy and other countries to provide material assistance. Many teachers relocated from rural to urban areas, leaving village schools understaffed and swelling the ranks of the unemployed in the cities; about 2,000 teachers fled the country. -The highly controlled environment that the communist regime had forced upon the educational system over the course of more than forty-six years was finally liberated set for improvement. In the late 1990, many schools were rebuilt or reconstructed, to improve learning conditions. Most of the improvements have happened in the larger cities of the country especially in Tirana.

In Tirana, there are 64 primary schools and 19 secondary schools.[104] The city is also host to many higher education institutions. This brings many young students from other cities and countries, especially from neighbouring countries, to Tirana. Many private Universities have been opened during the recent years. The French computer science university Epitech is also located in the city.

In recent years, foreign students mainly from Southern Italy are being enrolled at Italian-affiliated universities in Tirana in the hope of better preparing themselves for entrance exams in Italy's universities.

Media

.jpg)

As the capital, Tirana is the most significant location for the Albanian media industry whose content is distributed throughout Albania, Kosovo and other Albanian-speaking territories. Tirana is the home to most of the national and international television stations, including the national broadcaster, Radio Televizioni Shqiptar (RTSH), along with all its television and radio networks. The three largest Albanian commercial broadcasters, such as Televizioni Klan, Top Channel and Vizion Plus, also maintains their headquarters in the city. The European broadcaster, Euronews, operates a franchise in the city as well as the American broadcaster CNN.[105][106]

Tirana is also a principal location for the largest Albanian newspapers, magazines and publications. The newspapers with the largest circulations in Albania are published in Tirana, including Gazeta Shqip, Gazeta Tema, Koha Jonë and Panorama. Gazeta Shqiptare, one of the oldest Albanian-language newspapers in Albania, operates and has its headquarters in the city.[107] Tirana also has a well-established English-language newspaper, notably the daily of Tirana Times.

Culture

The city of Tirana offers a blend of traditional and diverse lifestyle with a variety of arts, food, entertainment, and night life, available in a form and abundance comparable to that in other capitals around Europe. Among the local institutions are the National Library, that keeps more than a million books, periodicals, maps, atlases, microfilms and other library materials. The city has five well-preserved traditional houses (museum-houses), 56 cultural monuments, eight public libraries.[108]

There are many foreign cultural institutions in the city, including the German Goethe-Institut,[109] Friedrich Ebert Foundation[110] and the British Council.[111] Other cultural centers in Tirana are, Canadian Institute of Technology, Chinese Confucius Institute, Greek Hellenic Foundation for Culture,[112] Italian Istituto Italiano di Cultura[113] and the French Alliance Française.[114] The Information Office of the Council of Europe was established in Tirana. The three main religions in Albania, which contains Islam, Orthodox and Catholic Christianity, have all their headquarters in Tirana. The Bektashi leadership moved to Albania and established their World Headquarters also in the city of Tirana.

One of the major annual events taking place in Tirana each year is the Tirana International Film Festival.[115] It was the first international cinema festival in the country and considered as the most important cinematic event in the country.

Architecture

Tirana is home to different architectural styles that represent influential periods in its history dating back to the antiquity. The architecture of Tirana as the capital of the country was marked by two totalitarian regimes, by the fascist regime of Benito Mussolini during World War II and the communist regime. Both have left their mark on the city with their typical architecture.

In addition to the objects of the architecture of the totalitarian regimes of the 20th century, Tirana offers a couple of other such objects of both periods. The Palace of Brigades (former Palace of the Albania's King Zog I), the ministries buildings, the government building and the municipality hall are designed by Florestano Di Fausto and Armando Brasini, both well-known architects of the Mussolini period in Italy. The Dëshmorët e Kombit Boulevard was built in 1930 and given the name King Zog I Boulevard.

In the communist period, the part from Skanderbeg Square up to the train station was named Stalin Boulevard. The Royal Palace or Palace of Brigades previously served as the official residence of King Zog I. It has been used by different Albanian governments for various purposes. Because of the outbreak of World War II, and the 1939 Italian invasion of Albania, King Zog I fled Albania and never had a chance to see the Palace fully constructed. The Italians finished it and used it as the Army Headquarters. The Palace took its nickname Palace of Brigades because it was taken from the Italians by a people's army brigade.[116]

In the 21st century, Tirana turned into a proper modernist city, with large blocks of flats, modern new buildings, new shopping centres and many green spaces. In June 2016, the Mayor of Tirana Erion Veliaj and the Italian architect Stefano Boeri announced the start of the works for the redaction of the Master Plan Tirana 2030.

The city of Tirana is a densely-built area but still offers several public parks throughout its districts, graced with green gardens. With an area of 230 hectare, the Grand Park is the largest park in the city. It is one of most visited areas by local citizens.[117] The park includes many children's playgrounds, sport facilities and landmarks such as the Saint Procopius Church, the Presidential Palace, the Botanical Gardens, the Tirana Zoo, the Amphitheatre, the Monument of the Frashëri Brothers and many others.

The Rinia Park was built during the Communist regime in Albania. It bordered by Dëshmorët e Kombit Boulevard to the east, Gjergi Fishta Boulevard and Bajram Curri Boulevard to the south, Rruga Ibrahim Rugova to the west and Rruga Myslym Shyri to the north. The Taivani Center is the main landmark in the park and houses cafés, restaurants, fountains, and a bowling lane in the basement. The Summer Festival takes place every year in the park, to celebrate the end of winter and the rebirth of nature and a rejuvenation of spirit amongst the Albanians. As of the Mayor of Tirana Erion Veliaj, the Municipality of Tirana will build more green spaces and will plant more trees.[118]

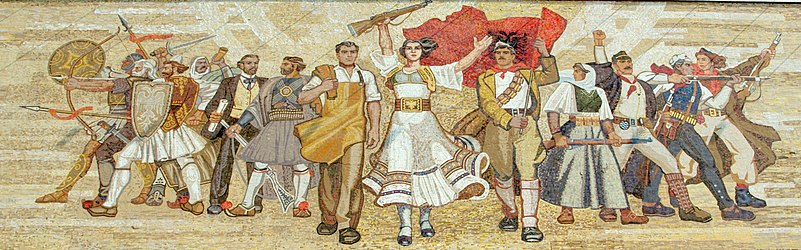

Museums

As one of the cultural centers of the country, Tirana is the home to a number of museums dedicated to a wide array of arts. The National Museum of History is located at the Skanderbeg Square and is the most representative of museums in the city.[119] The mosaic above the entrance is one of the most dominant features of the museum as it tells the story of how the Albanian people have fought against invasion and occupation throughout history.

Founded in 1948, the National Museum of Archaeology at the Mother Teresa Square displays a wide collection of research and discoveries belonging to the archaeological locations around the country.[120] It exhibits span from prehistory through antiquity and the middle ages to the twentieth century, offering an overview of the country's historical diversity.

The National Art Gallery is considered the most important gallery in Albania housing one of the greatest collections of paintings in the region.[122] Located at the Dëshmorët e Kombit Boulevard, it holds approximately 4.500 works of art including the most important collection of Albanian art of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries.

The Bunk'art Museum consists of two underground bunkers in Tirana built under the orders and direction of Enver Hoxha during the communist regime in the country. Located at the Fadil Deliu Street and Abdi Toptani Street respectively, the bunkers have been transformed into a history museum and contemporary art gallery with exhibits from the Second World War and Cold War.[123][124]

The Museum of Secret Surveillance was founded in 2017 and is housed within a twentieth century mansion, the building known as the House of Leaves, near the Dëshmorët e Kombit Boulevard.[125] It commemorates and honours the victims who fell to the communist terrorism and violence during the communist period in Albania. Other museums include the Natural Sciences Museum, which has branches in zoology, botany and geology, the former Enver Hoxha Museum and the Bunk'art Museum.

Festivals

.jpg)

In recent years, Tirana is becoming a popular hub for events, such as festivals. Their diversity makes possible for people of different tastes to find themselves in a city this small. Festivals provide entertainment for the youth as well as for adults. The Summer Day Festival (Albanian: Dita e Veres) takes place every year on 14 March celebrating the arrival of Spring, and is the country's largest pagan festival. It is widely celebrated in Tirana, Elbasan, and other cities in Albania as well as in the Arbëresh colonies in Italy.

In addition, Tirana Municipality organizes several food tastings festivals in rural Tirana in order to promote local organic products and stimulate agri-tourism. Notable events include the Tomato Festival in Shengjergj in Dajti Mt, and Olives Festival in Ndroq.

Another major event, the Tirana International Film Festival takes place in Tirana each year bringing a large number of artists to produce a wide range of interesting film works. Other festivals include the Tirana Jazz Festival, Tirana Biennial, Guitar Sounds Festival, Albanian Wine Festival, and sports events like track and field championships, Rally Albania, and mountain biking events.

In 2016, the first Telekom Electronic Beats Festival were held in Tirana, bringing the latest trends from the urban lifestyle to the Albanian youth.[127] This is in effort to increase the number of tourist visits to Tirana. However, the city is become a popular destination for many young people around the region during the vacation period.[128]

Cuisine

Along with Albanian cuisine, a variety of international cuisines are popular among the residents in Tirana. In 2016, Albania surpassed Spain by becoming the country with the most coffee houses per capita in the world with 654 coffee houses per 100,000 inhabitants.[129] This is due to coffee houses closing down in Spain due to the economic crisis, and the fact that as many cafes open as they close in Albania. In addition, the fact that it was one of the easiest ways to make a living after the fall of communism in Albania, together with the country's Ottoman legacy further reinforce its strong dominance in Albania.

Tirana's restaurant scene has evolved recently characterized by stylish interiors and delicious food grown locally. The Tirana region is known for the Fergesa traditional dish made with either peppers or liver,[130] and is found at a number of traditional restaurants in the city and agri-tourism sites on the outskirts of Tirana.

Sports

Being the capital, Tirana is the center of sport in Albania, where activity is organized across amateur and professional levels. It is home to many major sporting facilities. Starting from 2007, the Tirana Municipality has built up to 80 sport gardens in most of Tirana's neighborhoods. One of the latest projects is the reconstruction of the existing Olympic Park, that will provide infrastructure for most intramural sports.[131]

Tirana hosted in the past three major events, the FIBA EuroBasket 2006, 2011 World Mountain Running Championships and the 2013 European Weightlifting Championships.

There are two major stadiums, the former Qemal Stafa Stadium and the Selman Stërmasi stadium. The former was demolished in 2016 to make way for the new national stadium.[132] The new stadium called the Air Albania Stadium was constructed on the same site of the former Qemal Stafa Stadium and it is planned to open in late 2019. It will have an underground parking, Marriott Tirana Hotel, shops and bars and will be used for entertainment events. Tirana's sports infrastructure is developing fast because of the investments from the municipality and the government.

Football is the most widely followed sport in Tirana as well as in the country, having numerous club teams including the KF Tirana, Partizani Tirana, and Dinamo Tirana. It is popular at every level of society, from children to wealthy professionals. In football, as of April 2012, the Tirana-based teams have won a combined 57 championships out of 72 championships organized by the FSHF, i.e. 79% of them. Another popular sport in Albania is basketball, represented in particular by the teams KB Tirana, BC Partizani, BC Dinamo, Ardhmëria and also the women's PBC Tirana.

Recently two rugby teams were created: Tirana Rugby Club,[133] founded in 2013 and Ilirët Rugby Club[134] founded in 2016.

Notes

- Station ID for Tirana is 13615 Use this station ID to locate the sunshine duration

References

- "Profili i bashkisë Tiranë". 11 May 2015. Archived from the original on 14 August 2017. Retrieved 8 February 2018.

Popullsia: Sipas censusit të vitit 2011, në territorin e bashkisë së re Tiranë banojnë 557,422 banorë, ndërsa sipas Regjistrit Civil banojnë 757,361 banorë. Me një sipërfaqe prej 1,110.03 kilometrash katrorë, densiteti i popullsisë sipas të dhënave të Censusit është 502 banorë/ km2 ndërsa sipas Regjistrit Civil, densiteti është 682 banorë km2.

- "Popullsia e Shqipërisë" (PDF). instat.gov.al (in Albanian). 1 January 2018.

- "Subnational Human Development Index (2.1)". hdi.globaldatalab.org. Global Data Lab.

- "Sunniest Cities in Europe". currentresults.com. p. 1.

- "European Cities With the Wettest, Rainiest Weather". currentresults.com. p. 1.

- "Congratulations, Tirana! Winner of the European Youth Capital for 2022". youthforum.org. European Youth Capital. 21 November 2019. Retrieved 7 December 2019.

- http://www.qarkutirane.gov.al/sites/default/files/Koncepti%20i%20Zhvillimit%20Rajonal%20per%20Qarkun%20e%20Tiranes_0_0.pdf

- "Dajti National Park A Recreational Area for Citizens of Tirana, Albania" (PDF). boku.ac.at. p. 2.

- "Law nr. 115/2014" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 September 2015.

- Kottek, Markus; Grieser, Jürgen; Beck, Christoph; Rudolf, Bruno; Rube, Franz (June 2006). "World Map of the Köppen-Geiger climate classification updated" (PDF). Meteorologische Zeitschrift. 15 (3): 259–263. Bibcode:2006MetZe..15..259K. doi:10.1127/0941-2948/2006/0130. Retrieved 27 February 2011.

- "IMPACT OF CLIMATE CHANGE SCENARIOS ON THE PLANT HARDINESS ZONES OF TIRANA PREFECTURE". researchgate.net.

- Telegraph Media Group. "Mapped: the sunniest (and dullest) cities in Europe". The Daily Telegraph.

- "Klimatafel von Tirana (Flugh.) / Albanien" (PDF). Baseline climate means (1961–1990) from stations all over the world (in German). Deutscher Wetterdienst. Retrieved 30 January 2016.

- "Station 13615 Tirana". Global station data 1961–1990—Sunshine Duration. Deutscher Wetterdienst. Archived from the original on 17 October 2017. Retrieved 30 January 2016.

- "Station Tirana" (in French). Meteo Climat. Retrieved 11 June 2016.

- "Tirane (13615) - WMO Weather Station". NOAA. Retrieved 12 May 2019.

- d.o.o, Yu Media Group. "Tirana, Albania - Detailed climate information and monthly weather forecast". Weather Atlas. Retrieved 3 July 2019.

- "State of the Environment in Albania 1997-1998". Retrieved 18 February 2018.

- VizionPlusAlbania (7 November 2013). "Stoku i makinave të përdorura – News, Lajme – Vizion Plus" – via YouTube.

- "Environmental Center for Administration & Technology Tirana. 2008. Tirana Air Quality Report. Tirana: EU/LIFE Program; German Federal Ministry of the Environment, Nature Protection and Nuclear Safety" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 March 2012. Retrieved 20 May 2020.

- "Dako, Alba; Lika, Mirela and Hysen Mankolli. 2008. Monitoring aspects of air quality in urban areas of Tirana and Tirana and Durrës, Albania" (PDF). Natura Montenegrina. 7 (2): 549–557. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 March 2012. Retrieved 21 January 2013.

- Cameron, Rob (3 December 2004). "Tirana: Where the streets have no name". BBC News.

- "Oranews.tv – Veliaj: Në Farkë do ndërtohet terminali i autobusave për juglindjen". Oranews. Archived from the original on 22 August 2015. Retrieved 31 August 2015.

- "HOME". planifikimi.gov.al.

- "Baza Ligjore - APR Tirana". aprtirana.al.

- "Natural and anthropogenic hazards in karst areas of Albania" (PDF). nat-hazards-earth-syst-sci.net. p. 9.

- "Community Based Tourism at Pellumbas Village, Albania" (PDF). web.wpi.edu. p. 4.

- University of London. Bulletin of the Institute of Archaeology. The Institute, 1994. pp. 110–111.

- Hammond, Nicholas Geoffrey Lemprière (1966). "The Kingdoms in Illyria circa 400-167 B.C.". The Annual of the British School at Athens. British School at Athens. 61: 247. JSTOR 30103175.

- Heppner, Harald (1994). Hauptstädte in Südosteuropa: Geschichte, Funktion, nationale Symbolkraft. Wien u.a. Böhlau. pp. 133, 135. ISBN 978-3-205-98255-5.

- Heppner, Harald (1994). Hauptstädte in Südosteuropa: Geschichte, Funktion, nationale Symbolkraft. Wien u.a. Böhlau. p. 137. ISBN 978-3-205-98255-5.

- E. J. Van Donzel (1994), Islamic Desk Reference, E.J. Brill, p. 451, ISBN 9780585305561, OCLC 45731063,

"il borgo di Tirana" is already mentioned as early as 1572

- Koco Miho (1987). J.Tocka (ed.). Trajta të profilit urbanistik të qytetit të Tiranës : prej fillimeve deri më 1944. Tirana: 8 Nëntori. p. 57. OCLC 20994870.

- ""Tiranasit" e ardhur rishtaz" (in Albanian). Gazeta Shqiptare. Retrieved 17 August 2008.

- "Klan magazine". Klan (527–534): 265. 2007. Retrieved 10 October 2018.

- Clayer, Nathalie (2005). "The Albanian students of the Mekteb-i Mülkiye: Social networks and trends of thought". In Özdalga, Elisabeth (ed.). Late Ottoman Society: The Intellectual Legacy. Routledge. pp. 306–307. ISBN 9780415341646.

- Pearson, Owen (2006). Albania and King Zog: independence, republic and monarchy 1908–1939. IB Taurus. p. 140. ISBN 1-84511-013-7.

It was decided that the Congress of Lushnje was not to be dissolved until elections had been held and the new government had taken power into its hands and begun to exercise its functions in Tirana, in opposition to the Provisional Government in Italian occupied Durrës

- Kera, Gentiana. Aspects of the urban development of Tirana: 1820–1939 Archived 25 March 2012 at the Wayback Machine, Seventh International Conference of Urban History. Athens, 2004.

- Stefanović, Djordje (2005). "Seeing the Albanians through Serbian eyes: The Inventors of the Tradition of Intolerance and their Critics, 1804–1939." European History Quarterly. 35. (3): 470.

- Bleta, Indrit. Influences of political regime shifts on the urban scene of a capital city, Case Study: Tirana. Turkey, 2010.

- "Mother Teresa". Biography. Retrieved 10 May 2020.

- Kempster, Norman. "Albanians Mob Baker, Cheer U.S. : Europe: 'Freedom works,' he exhorts a rally of 200,000. The country hopes for aid to rebuild an economy shattered by lengthy Stalinist isolation". Los Angeles Times.

- "A bright and colourful new style of urban design emerges in Albania". Resource for Urban Design Information. Retrieved 16 August 2008.

- Pusca, Anca (2008). "The aesthetics of change: Exploring post-Communist spaces" (PDF). Global Society. 22 (3): 369–386. doi:10.1080/13600820802090512.

- "Garden Villas, Farke". Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 2 September 2015.

- "Longhill". longhillresidence.com. Retrieved 2 September 2015.

- "Bush greeted as hero in Albania". BBC News. 10 June 2007. Retrieved 10 May 2020.

- "Protesters killed in Tirana rally". Southeast European Times. 21 January 2011. Retrieved 15 September 2011.

- "Mustafa Matohiti Street – Rruga e Salës". spottedbylocals.com. Retrieved 13 April 2017.

Mustafa Matohiti Street is known as Rruga e Salës among the locals. The street has unofficially gotten this name because the ex-Prime Minister of Albania, Sali Berisha, lives there.

- "Erion Veliaj takes office as Mayor of Tirana". Retrieved 31 August 2015.

- "Reforma Territoriale – Harta – 61 bashki". reformaterritoriale.al. Retrieved 31 August 2015.

- "Veliaj suspends construction permits". Retrieved 31 August 2015.

- "Tirana City Council approves the allocation of social housing for 242 families". Retrieved 31 August 2015.

- "New urban plan,Tirana Mayor: The new plan projects Tirana of the future". Archived from the original on 19 February 2017. Retrieved 18 February 2017.

- "Albania: largest cities and towns and statistics of their population". World Gazetteer. Archived from the original on 5 December 2012. Retrieved 12 June 2020.

- "Të dhëna të përgjithshme për Qytetin e Tiranës" (PDF) (in Albanian). Bashkia Tiranë. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 September 2008. Retrieved 12 June 2020.

- "Popullsia e Shqipërisë" (PDF) (in Albanian). Instituti i Statistikës (INSTAT). 19 February 2016. Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 April 2016. Retrieved 12 June 2020.

- "Popullsia e Shqipërisë" (PDF) (in Albanian). Instituti i Statistikës (INSTAT). 13 February 2017. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 May 2017. Retrieved 12 June 2020.

- Citation regarding the Albanian censuses of 1989 and 2001:

- Gjonça, Arjan; Elezi, Pranvera; Sado, Lantona. "Pabarazitë në Tiranën e madhe" (PDF) (in Albanian). Instituti i Statistikës (INSTAT). p. 8. Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 June 2020. Retrieved 12 June 2020.

- "Censusi i popullsisë dhe banesave/ Population and Housing Census–Tiranë 2011" (PDF) (in Albanian). Tirana: Instituti i Statistikës (INSTAT). p. 85. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 August 2017. Retrieved 20 July 2020.

- "Population – INSTAT". Instituti i Statistikës (INSTAT). Archived from the original on 16 March 2013. Retrieved 20 July 2020.

- See table: "Population growth of Tirana in selected periods"

- "Censusi i popullsisë dhe banesave / Population and Housing Census – Tiranë 2011" (PDF) (in Albanian). Tirana: Instituti i Statistikës (INSTAT). 2013. pp. 38–39. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 August 2017. Retrieved 20 July 2020.

- "Religion in the Municipality of Tirana 2011". Instituti i Statistikës (INSTAT). Archived from the original on 22 January 2019. Retrieved 20 July 2020.

- "Constitution of the Republic of Albania". Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE). p. 2. Retrieved 20 July 2020.

- "Albania 2016 International Religious Freedom Report" (PDF). United States Department of State. pp. 1–7. Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 August 2017. Retrieved 20 July 2020.

- "Instat Gis". Instituti i Statistikës (INSTAT).

- "Constitution of the Republic of Albania". Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE). p. 3. Retrieved 8 June 2020.

The capital city of the Republic of Albania is Tirana

- "Presidency". Bashkia Tiranë. Archived from the original on 19 July 2020. Retrieved 19 July 2020.

- "The Prime Minister Offices". Bashkia Tiranë. Archived from the original on 19 July 2020. Retrieved 19 July 2020.

- "Albania's Assembly Hall". Bashkia Tiranë. Archived from the original on 19 July 2020. Retrieved 19 July 2020.

- "Foreign Embassies and Consulates in Albania". embassy.goabroad.com.

- Dorina Pojani (6 March 2010). "Tirana City Profile". Cities. 27: 483–495. doi:10.1016/j.cities.2010.02.002.

- "Bashkia – Lajmet e Ditarit". Tirana.gov.al. Retrieved 15 September 2011.

- "International Relations" (PDF). Municipality of Tirana. tirana.gov.al. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 October 2011. Retrieved 23 June 2009.

- "MINA Breaking News - Skopje and Tirana sign Twin cities memorandum". macedoniaonline.eu.

- "50,7% of Albanian Employees Work in Agriculture". agroweb.org. 26 May 2017.

- "The History, Form and Function of the Old Bazaar in Tirana". academia.edu.

- "Analysis of the Albanian Banking System in the Transition Years" (PDF). ijbcnet.com.

- Muharremi, =Oltiana; Madani, Filloreta; Pelari, Erald. "The Development of the Service Sector in Albania and Its Future". researchgate.net. pp. 2–9.

- "TOURISM AND EMPLOYMENT IN ALBANIA – IS THERE A STRONG CORRELATION?" (PDF). asecu.gr. pp. 1–9.

- "Mayor Veliaj in Singapore: Tirana, a place beyond belief". Radio Tirana International.

- "Turizmi në Tiranë, fluks nga Evropa, Azia e Australia". forum-al.com (in Albanian). Tirana. 11 August 2018.

- "Veliaj: Ambicia jonë është që Tirana të kapë 1 milion turistë këtë vit". ata.gov.al (in Albanian). Tirana.

- "US giant Hyatt takes over former Sheraton Tirana management". Tirana Times.

- Jonuzaj, Klaudjo. "Marriott to open hotel in Albania's Tirana - govt". SEE News.

- "Statistikat e transportit" (PDF) (in Albanian). Instituti i Statistikës (INSTAT). 27 January 2019. p. 2. Retrieved 13 June 2020.

- "Strategjija e Zhvillimit të Qendrueshëm të Bashkisë Tiranë 2018-2022" (PDF) (in Albanian). Bashkia Tiranë. pp. 18, 23. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 June 2020. Retrieved 13 June 2020.

- "Albania economy briefing: Tirana's Outer Ring Road and the controversial case of 2.1 km segment". Cooperation between China and Central and Eastern European Countries (China-CEE). 6 March 2019. Retrieved 13 June 2020.

- "Unaza e Madhe e Tiranës hapet në shtator" (in Albanian). TV Klan. 14 August 2017. Retrieved 13 June 2020.

- "Lamtumira e trenit në kryeqytet, stacioni tashmë zhvendoset në Vorë" (in Albanian). Gazeta Shqip. 1 September 2013. Retrieved 14 June 2020.

- "New Public Transport Terminal of Tirana". Italferr. Retrieved 14 June 2020.

- "Tirana me stacion modern multimodal" (in Albanian). Koha. 2 May 2018. Retrieved 14 June 2020.

- "Linja hekurudhore Durrës – Tiranë – Rinas, detajet e projektit" (in Albanian). Radio Televizioni Shqiptar (RTSH). 10 July 2018. Retrieved 14 June 2020.

- "Rikthehet hekurudha, linja Tiranë-Durrës pritet të nisë punimet në qershor" (in Albanian). Euronews Albania. 12 February 2020. Retrieved 14 June 2020.

- "Tirana plans to develop two tram lines - Railway PRO Communication Platform". 26 June 2013.

- "Pas rikonfirmimit për mandatin e dytë, Veliaj ftohet nga BERZH për vijimin e investimeve në Tiranë" (in Albanian). Administrata.al. Retrieved 14 June 2020.

- Burgen, Stephen (29 October 2018). "Build it and they will come: Tirana's plan for a 'kaleidoscope metropolis". Tirana: The Guardian. Retrieved 14 June 2020.

- "Tirana është kthyer në qytetin me më shumë korsi biçikletash në Shqipëri" (in Albanian). TRT. 14 July 2018. Retrieved 14 June 2020.

- "Ecovolis". Ecovolis. Archived from the original on 6 January 2012. Retrieved 21 January 2013.

- Christiaens, Jan (1 August 2014). "Public bike service opens in Tirana (Albania)". Eltis. Retrieved 14 June 2020.

- Global, Mobike (8 June 2018). "Mobike Launches in Tirana, Albania". Mobike. Retrieved 14 June 2020.

- "Mobike ngushton hartën e përdorimit në Tiranë" (in Albanian). Radio Televizioni Shqiptar (RTSH). 17 January 2019. Retrieved 14 June 2020.

- "Veliaj me mësues e edukatorë: Në 4 vite hapim 100 kopshte e 200 shkolla". forum-al.com.

- Euronews, Michael (23 November 2019). "Michael Peters welcomes Euronews Albania to the Euronews family". Euronews Albania. Retrieved 14 June 2020.

- "Televizioni A2, partneri ekskluziv i CNN në Shqipëri, nis rekrutimin e stafit" (in Albanian). Telegrafi. 25 April 2018. Retrieved 14 June 2020.

- Stegherr, Marc; Liesem, Kerstin. Die Medien in Osteuropa: Mediensysteme im Transformationsprozess (in German). Springer-Verlag. pp. 159–166. ISBN 9783531924878. Retrieved 14 June 2020.

- (in Albanian) Statistikat 2007 Archived 11 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine PDF Municipality of Tirana. Retrieved 20 July 2008

- "Goethe-Zentrum". goethe.al.

- "Home - Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung Tirana". fes-tirana.org.

- "British Council - Albania". britishcouncil.al.

- "Tiranas Centre of Hellenic Foundation of Culture - Anna Lindh Foundation". annalindhfoundation.org.

- "Istituto Di Cultura - Tirana". iictirana.esteri.it.

- "Aleanca Franceze - Frengjishtja, gjuha e europes". aftirana.org.

- "TIFF - TIRANA INTERNATIONAL FILM FESTIVAL". tiranafilmfest.com.

- "Municipality of Tirana, partner in a transnational project on totalitarian architecture". atrium-see.eu.

- "Mayor of Tirana inaugurates second workout area at Artificial Lake Park". 23 February 2017.

- "Second paid parking space inaugurated in Tirana". top-channel.tv. Retrieved 10 May 2020.

- "National Historical Museum". Bashkia Tiranë. Archived from the original on 18 July 2020. Retrieved 18 July 2020.

- "National Archaeological Museum". Bashkia Tiranë. Retrieved 18 July 2020.

- ""The Cloud" - Art Pavilion at National Gallery Gardens" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 August 2018. Retrieved 18 February 2018.

- "National Gallery of Arts". Bashkia Tiranë. Archived from the original on 18 July 2020. Retrieved 18 July 2020.

- "Bunk'Art 1". Bashkia Tiranë. Archived from the original on 18 July 2020. Retrieved 18 July 2020.

- "Bunk'Art 2". Bashkia Tiranë. Archived from the original on 18 July 2020. Retrieved 18 July 2020.

- "The Museum of Secret Surveillance". Bashkia Tiranë. Archived from the original on 18 July 2020. Retrieved 18 July 2020.

- "Castle of Tirana ready for the public; Veliaj invites also those who were against". Oculus News.

- "Telekom Electronic Beats introduced in Albania". telekom.com.al. 23 July 2016.

- "Tirana më e vizitueshmja nga turistët e huaj". ata.gov.al.

- "Albania ranked first in the World for the number of Bars and Restaurants per inhabitant". Oculus News.

- "Albanian Fergese - Fergesë e Tiranës me piperka". My Albanian Food.

- "Me sportistët elitar, prezantohet Parku Olimpik i Tiranës". arsimi.gov.al. Retrieved 31 August 2015.

- Shembet "Qemal Stafa" (25 June 2016). "Shemben 4 tribuna, lamtumirë stadiumi "Qemal Stafa" (FOTO)". Panorama (in Albanian).

- "Tirana Regbi Klub kthen sportin e munguar në kryeqytet". sportekspres.com.

- "OSCE Presence in Albania launches sports-based youth development programme - OSCE". osce.org.

Further reading

- Akkam, Alia (13 October 2017). "The Capital of Albania Has Transformed into a Lively, Affordable Destination". Vogue.

- Hillsdon, Mark (27 February 2017). "The European capital you'd never thought to visit (but really should)". The Telegraph.

- Crevar, Alex (28 August 2015). "Tirana, Breaking Free From Communist Past, Is a City Transformed". The New York Times.

- Blocal, Giulia (16 September 2014). "Tirana's colorful buildings". Blocal Travel blog.

- Williams, Sean (11 July 2014). "Tirana fights to beat its addiction to cars and get its residents cycling". The Guardian. Retrieved 12 July 2014.

- McRae, Hamish (13 September 2008). "Albania: Charmed by Tirana". The Independent.

- Abitz, Julie. Post-Socialist Development in Tirana. Roskilde: Roskilde Universitetscenter, 2006.

- Agorastakis, Michalis; Sidiropoulos, Giorgos (2007). "Population change due to geographic mobility in Albania, 1989–2001, and the repercussions of internal migration for the enlargement of Tirana". Population, Space and Place. 13 (6): 471–481. doi:10.1002/psp.463.

- Aliaj, Besnik; Keida Lulo and Genc Myftiu. Tirana: the Challenge of Urban Development, Tirana: Cetis, 2003 ISBN 99927-880-0-3

- Aliaj, Besnik. A Short History of Housing and Urban Development Models during 1945–1990, Tirana 2003.

- Bertaud, Alain. Urban Development in Albania: the Success Story of the Informal Sector, 2006.

- Bleta, Indrit. Influences of Political Regime Shifts on the Urban Scene of a Capital City, Case Study: Tirana. Turkey, 2010.

- Capolino, Patrizia (2011). "Tirana: A Capital City Transformed by the Italians". Planning Perspectives. 26 (4): 591–615. doi:10.1080/02665433.2011.601610.

- Felstehausen, Herman. Urban Growth and Land Use Changes in Tirana, Albania: With Cases Describing Urban Land Claims. University of Wisconsin-Madison, 1999

- Galeteanu, Emira. Tirana: the Spectacle of the Urban Theatre. MA Dissertation. Carleton University: Ottawa, 2006.

- Guaralda, Mirko (2009). Urban Identity and Colour : the Case of Tirana, Albania. Spectrum e-news, 2009(Dec), pp. 13–14.

- Jasa, Skënder. Tirana në shekuj: Terona, Theranda, Tirkan, Tirannea, Tirana: monografi, disa artikuj e materiale arkivore kushtuar historisë së Tiranës, Tirana 1997.

- Kera, Gentiana. Aspects of the Urban Development of Tirana: 1820–1939, Seventh International Conference of Urban History. Athens, 2004.

- Nase, Ilir; Ocakci, Mehmet (2010). "Urban Pattern Dichotomy in Tirana: Socio-spatial Impact of Liberalism". European Planning Studies. 18 (11): 1837–1861. doi:10.1080/09654313.2010.512169.

- Pojani, Dorina (2011). Mobility, Equity and Sustainability Today in Tirana, TeMA 4, no. 2, pp.99–109

- Pojani, Dorina (2010). "Tirana". Cities. 27 (6): 483–495. doi:10.1016/j.cities.2010.02.002.

- Pojani, Dorina (2011). "From Carfree to Carfull: the Environmental and Health Impacts of Increasing Private Motorisation in Albania". Journal of Environmental Planning and Management. 54 (3): 319–335. doi:10.1080/09640568.2010.506076.

- Pojani, Dorina (2011). "Urban and Suburban Retail Development in Albania's Capital After Socialism". Land Use Policy. 28 (4): 836–845. doi:10.1016/j.landusepol.2011.02.001.

- Alien by Alexandra Lewis, RTV Ora, Tirana, Albania, 2019, a TV series produced by domestic RTV Ora on life in Albania seen by a foreigner, Australian-born journalist Alexandra Lewis living in Tirana, Albania

External links

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Tirana. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Tirana. |

- Municipality of Tirana (in Albanian)

- . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). 1911.