Dropull

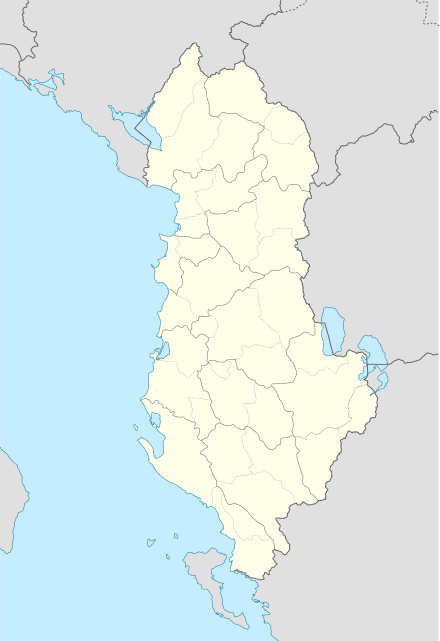

Dropull (Albanian: Dropulli; Greek: Δρόπολης, Dhropolis) is a municipality and a predominantly Greek-inhabited region in Gjirokastër County, in southern Albania. The region stretches from south of the city of Gjirokastër to the Greek–Albanian border, along the Drino river. The region's villages are part of the Greek "minority zone" recognized by the Albanian government, in which live majorities of ethnic Greeks.[1]

Dropull | |

|---|---|

Dawn near Jorgucat | |

Emblem | |

Dropull | |

| Coordinates: 39°59′N 20°14′E | |

| Country | |

| County | Gjirokastër |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Dhimitraq Toli (PS) |

| Area | |

| • Municipality | 448.45 km2 (173.15 sq mi) |

| Population (2011) | |

| • Municipality | 3,503 |

| • Municipality density | 7.8/km2 (20/sq mi) |

| Time zone | UTC+1 (CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+2 (CEST) |

| Area Code | (0)884 |

| Vehicle registration | AL |

| Website | Official Website |

The municipality Dropull was created in 2015 by the merger of the former municipalities Dropull i Poshtëm, Dropull i Sipërm and Pogon. The seat of the municipality is the village Sofratikë.[2] According to the 2011 census the total population is 3,503,[3] while according to the civil registry of that year it is 23,247.[4] The municipality covers an area of 448.45 km2.[5]

History

During the Middle Helladic period (2100-1550 BC), a double tumulus was dug out in Vodhinë, with strong similarities to the grave circles at Mycenae, showing a common ancestral link with the Myceneans of southern Greece.[6] In classical antiquity, the area was inhabited by the Greek tribe of the Chaonians.

From the Roman period there was a settlement named Hadrianopolis (of Epirus) in the region, one of several named after the great Roman emperor Hadrian. The settlement was built on a strategic spot in the valley of the river Drino near the modern village of Sofratikë, 11 kilometers south of Gjirokastër.

The foundations of Hadrianopolis were first discovered in 1984 when upper sections of the amphitheater were noticed by local farmers. Italian and Albanian archaeologists subsequently excavated much of the site, revealing a full amphitheater, Roman baths, and changing rooms. The site of the agora (forum) has been detected using ground radar, and excavation is expected in the period 2018 onwards. In the amphitheater, there are post holes for iron railings on first row seats. Also some "changing rooms" - originally for actors - were converted to holding pens for wild animals. This was a site where Romans fed enemies of the state to wild animals.

During the 6th century the Byzantine emperor Justinian I, as part of his fortification plans against barbarian invasions, moved the settlement 4 kilometers southeast in the modern village of Peshkëpi, in order to gain a more secure position. The city is also referred in Byzantine sources as Ioustinianoupolis (or Justinianopolis, after him. Today, ruins of the fortifications are still visible, as are the aqueduct and a medieval Orthodox Christian church.[7]

During the 11th century the city was named Dryinoupolis, a name possibly deriving from its former name or from the nearby river. It was also, from the 5th century, the see of a bishopric (initially part of the Diocese of Nicopolis, Naupactus and then Ioannina).

In 1571 a short lived rebellion broke out under Emmanuel Mormoris, but Ottoman control was restored that same year.[8]

During the 16th and 17th centuries at least 11 Orthodox monasteries were erected in the region with the support of the local population. This unprecedented increase in the number of monasteries has led many scholars to name Dropull as "little Mount Athos".[9]

At the end of the 19th century, many inhabitants migrated to the United States.[10]

Religion

At c. 400 a bishopric was established as Diocese of Hadrianopolis in Epirus, a suffragan of the Metropolitan Archdicoese of Nicopolis, capital of the Late Roman province of Epirus Vetus. It was suppressed by the Pope c. 1000, but later got an Orthodox successor. The bishopric of Dryinoupolis included the region of modern southwest Albania and from the early 16th century its center was Argyrokastro (modern Gjirokastër).[11]

List of monasteries

- Monastery of the Prophet Elias, near Jorgucat (founded before 1586)

- Annunciation Monastery, Vanishtë (before 1617)

- Dormition of the Theotokos or Ravenia Monastery, Kalogoranxi (6th century)

- Dorminition of the Theotokos, Koshovicë (17th century)

- Monastery of Saints Quiricus and Julietta or Dhuvjan Monastery, Dhuvjan (1089)

- Dorminition of the Theotokos or Driyanou Monastery, between Bularat and Zervat

- Monastery of the Taxiarchs Michael and Gabriel, Derviçan (16th century)

- Dormition of the Theotokos, Frashtan (16th century)

- Monastery of the Holy Trinity, Pepel (1754)

- Nativity of the Theotokos or Zonarion or Kakiomenou Monastery, Lovinë (before 1761), abandoned in 20th century due to proximity to the Greek-Albanian border

- Theotokos Monastery (10th century), Zervat, abandoned during the crusades (11th century)

Catholic titular see

The Catholic diocese was nominally restored in 1933 as Latin Titular bishopric of Hadrianopolis in Epiro (Latin; adjective Hadrianopolitan(us) in Epiro) / Adrianopoli di Epiro (Curiate Italian).[12] It is vacant since decades, had had only the following incumbent of the fitting Episcopal (lowest) rank: Josef Freusberg (1953.04.12 – death 1964.04.10), as Auxiliary Bishop of Fulda (Germany) (1953.04.12 – 1964.04.10).

Notable locals

- Politics

- Grigorios Lambovitiadis, activist of the Northern Epirus movement

- Spiro Ksera, politician

- Vasilios Sahinis, leader of the Northern Epirote Liberation Organization

- Culture and sports

- Kosmas Thesprotos, scholar

- Leonidas Kokas

- Lefter Millo, international soccer player, capped with the Albania national football team

- Tasos Vidouris, poet

- Kleoniki Delijorgji, Miss Shqipëria 2012 and Miss Globe International 2012[13]

- Konstantinos Koufos (singer), singer[14]

See also

- Deropolitissa

- Peshkëpi killing

References

- "Second Report Submitted by Albania Pursuant to Article 25, Paragraph 1 of the Framework Convention for the Protection of National Minorities" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on March 19, 2009.

- "Law nr. 115/2014" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-09-24. Retrieved 2015-03-22.

- "Population and housing census - Gjirokastër 2011" (PDF). INSTAT. Retrieved 2019-09-25.

- "Gjirokastra's communes". Retrieved 13 January 2016.

- "Correspondence table LAU – NUTS 2016, EU-28 and EFTA / available Candidate Countries" (XLS). Eurostat. Retrieved 2019-09-25.

- Komita, Nuobo (1982). "The Grave Cicles at Mycenae and the Early Indo-Europeans" (PDF). Research Reports of Ikutoku Tech. Univ. (A-7): 59–70.

- Epirus, 4000 years of Greek history and civilization. M. V. Sakellariou. Ekdotike Athenon, 1997. ISBN 960-213-371-6, p. 154, 191

- Konstantinos., Giakoumis (2002). "The monasteries of Jorgucat and Vanishte in Dropull and of Spelaio in Lunxheri as monuments and institutions during the Ottoman period in Albania (16th-19th centuries)": 21. Retrieved 8 July 2018. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Konstantinos., Giakoumis (2002). "The monasteries of Jorgucat and Vanishte in Dropull and of Spelaio in Lunxheri as monuments and institutions during the Ottoman period in Albania (16th-19th centuries)": 125. Retrieved 8 July 2018. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Religion in Post-Communist Albania. Muslims, Christians and the idea of ‘culture’ in Devoll, Southern Albania. Gilles de Rapper. p. 7

- Albania's captives. Pyrrhus J. Ruches. Argonaut, 1965, p/

- "Bishops who are not Ordinaries of Sees: FR… – FZ…". www.gcatholic.org. Retrieved 22 April 2018.

- "Miss Globe International 2012: η Κλεονίκη Δεληγιώργη". politikanet.gr. Retrieved 27 January 2014.

- "Κωνσταντίνος Κουφός (Personas) - Η αποκάλυψη on air για την καταγωγή του (βίντεο)" (in Greek). 2015-11-25. Retrieved 2016-09-02.