Sotiates

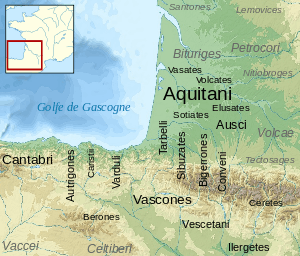

The Sotiates were a Gallic-Aquitani tribe, dwelling in the region surrounding Sos (Lot-et-Garonne).[1]

They are mentioned by Julius Caesar in the Commentarii de Bello Gallico, his firsthand account of the Gallic Wars, where he narrates the expedition of P. Licinius Crassus to Aquitania.

Name

They are mentioned as Sotiates (var. sontiates, sociates) by Caesar (mid-1st c. BC),[2] and as Sottiates by Pliny (1st c. AD).[3][4]

The meaning of the name Sotiates is unclear. The suffix is possibly the Gaulish -ates ('belonging to'), which appears in the names of many Gallic tribes across Europe (e.g., Atrebates, Nantuates, Caeracates).[1][5] The origin of the first element Soti- is unknown.[1]

The city of Sos, attested as oppidum Sotiatum in the 1st c. BCE (archidiaconatus Socientis in the late 13th c. CE) is named after the tribe.[1]

Culture

The ethnic identity of the Sotiates is debated.[6][7] Their lifestyle was very similar to that of the Gauls, which led some scholars to postulate that they were originally a Gallic people that had settled at the frontier of Aquitania.[7] In the mid-first century BCE, led by their chief Adiatuanos, the Sotiates fought alone against the Roman armies of Crassus, whereas other Aquitani tribes had formed a coalition against the foreign invader.[7] Furthermore, the name Adiatuanos is probably related to the Gaulish adiantu- ('eagerness, desire, ambition'; perhaps cognate with the Middle Welsh add-iant 'wish'),[8][9][10] and thus may be translated as 'zealously striving (for rulership)'.[9] Caesar mentions that their chief was protected by a troop of 600 men named soldurii, which could be a Latinized form of Gaulish soldurio ('body-guard, loyal, devoted') according to Xavier Delamarre.[11] Theo Vennemann argues on the contrary that the name may be of Aquitanian (Vasconic) origin, since it is used by the local people (illi), and the first element of sol-durii could be related to the Basque zor ('debt').[6] In any case, the soldurii of Adiatuanos were probably involved in a patron-client relationship that has been compared to the Gallic ambactus, and the size of his army (600 men) illustrates the concentration of a personal power ruling over different clans.[12]

They may also have been an Aquitanian tribe that had been Celticized before Caesar's first historical accounts. A sword found in a funeral near Sotiatum and dated to the 3rd century BCE attests the diffusion of prestigious items of Celtic (La Tène) type among the local population.[13] Joaquín Gorrochategui notes that the province of Aquitania experienced "a profound Gallic influence, which becomes more evident as one moves away from the Pyrenees northwards and eastwards. Evidence of this penetration are the names of Gallic persons and deities, the names of tribes in -ates, and later the Romance toponyms in -ac".[5]

Geography

Their capital was the oppidum Sotiatum (Sot(t)ium; present-day Sos),[14][9] located at the confluence of the Gueyze and Gélise rivers.[14]

History

The Sotiates are mentioned in two classical sources: Caesar's Bellum Gallicum and Cassius Dio's History of Rome.[15][16]

Gallic Wars (58–50 BC)

In 56 BCE, the Sotiates were led by their chief Adiatuanos in the defence of their oppidum against the Roman officer P. Licinius Crassus. After a failed sortie attempt with 600 of his soldurii, Adiatuanos had to capitulate to the Romans.[9]

[Cassius] then marched his army into the borders of the Sotiates. Hearing of his approach, the Sotiates collected a large force, with cavalry, in which lay their chief strength, and attacked our column on the march. First of all they engaged in a cavalry combat; then, when their cavalry were beaten, and ours pursued, they suddenly unmasked their infantry force, which they had posted in ambush in a valley. The infantry attacked our scattered horsemen and renewed the fight.

The battle was long and fierce. The Sotiates, with the confidence of previous victories, felt that upon their own courage depended the safety of all Aquitania: the Romans were eager to have it seen what they could accomplish under a young leader without the commander-in-chief and the rest of the legions. At last, however, after heavy casualties the enemy fled from the field. A large number of them were slain; and then Crassus turned direct from his march and began to attack the stronghold of the Sotiates. When they offered a brave resistance he brought up mantlets and towers.

The enemy at one time attempted a sortie, at another pushed mines as far as the ramp and the mantlets—and in mining the Aquitani are by far the most experienced of men, because in many localities among them there are copper-mines and diggings. When they perceived that by reason of the efficiency of our troops no advantage was to be gained by these expedients, they sent deputies to Crassus and besought him to accept their surrender.

Their request was granted, and they proceeded to deliver up their arms as ordered. Then, while the attention of all our troops was engaged upon that business, Adiatunnus, the commander-in-chief, took action from another quarter of the town with six hundred devotees, whom they call vassals. The rule of these men is that in life they enjoy all benefits with the comrades to whose friendship they have committed themselves, while if any violent fate befalls their fellows, they either endure the same misfortune along with them or take their own lives; and no one yet in the memory of man has been found to refuse death, after the slaughter of the comrade to whose friendship he had devoted himself. With these men Adiatunnus tried to make a sortie; but a shout was raised on that side of the entrenchment, the troops ran to arms, and a sharp engagement was fought there. Adiatunnus was driven back into the town; but, for all that, he begged and obtained from Crassus the same terms of surrender as at first.

— Julius Caesar. Bellum Gallicum. 3, 20–22. Loeb Classical Library. Translated by H. J. Edwards, 1917.

See also

References

- Nègre 1990, p. 167.

- Caesar. Commentarii de Bello Gallico, 3:20:3; 3:21:1

- Pliny. Naturalis Historia, 4:108

- Falileyev 2010, p. entry 6681.

- Gorrochategui 2011, p. 31: "L'Aquitaine a subi aussi une profonde influence gauloise, plus remarquable au fur et à mesure que l'on s’éloigne des Pyrénées vers le nord et l'est de la région. Les témoins de cette pénétration sont : les noms de personnes et de divinités gauloises, les noms de peuples en -ates, et postérieurement les toponymes romans en -ac. Cette influence se limite toujours à l’Aquitaine, sans que les territoires hispaniques du versant méridional des Pyrénées aient été affectés, sauf d’une manière très faible."

- Vennemann 2003, p. 695.

- Brèthes 2012, p. 37: "Nos seules certitudes concernent le peuple des Sotiates qui vit, combat, bat monnaie et s’administre comme un peuple gaulois. Comme les Gaulois, il a donc un oppidum, un site fortifié utilisé en cas d’attaque, que l’on situe dans la région de Sos, en Lot-et-Garonne. Si nous ajoutons à ces faits troublants que ce peuple se bat seul contre Crassus sous les ordres de son roi Adiatuanos, alors que tous les autres peuples aquitains forment une coalition, nous pouvons émettre l’hypothèse qu’il pourrait s’agir de Gaulois installés aux marches de l’Aquitaine."

- Delamarre 2003, p. 32.

- Spickermann 2006.

- Matasović 2009, p. 434.

- Delamarre 2003, p. 277.

- Berrocal-Rangel & Gardes 2001, p. 130.

- Beyneix & Couhade 1996, p. 62.

- Beyneix & Couhade 1996, p. 57.

- Julius Caesar. Bellum Gallicum. 3, 20–22.

- Cassius Dio. Ῥωμαϊκὴ Ἱστορία (Historia Romana). 39, 46.

Bibliography

- Berrocal-Rangel, Luis; Gardes, Philippe (2001). Entre Celtas e Íberos (in Spanish). Real Academia de la Historia. ISBN 978-84-89512-82-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Beyneix, Alain; Couhade, Cynthia (1996). "Une sépulture à armement de type celtique à Sos-en-Albret (Lot-et-Garonne)". Études celtiques. 32 (1): 57–63. doi:10.3406/ecelt.1996.2084.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Brèthes, Jean-Pierre (2012). "Et l'Aquitaine devint romaine". Modèles linguistiques (in French). XXXIII (66): 29–45. doi:10.4000/ml.285. ISSN 2274-0511.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Delamarre, Xavier (2003). Dictionnaire de la langue gauloise: Une approche linguistique du vieux-celtique continental (in French). Errance. ISBN 9782877723695.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Falileyev, Alexander (2010). Dictionary of Continental Celtic Place-names: A Celtic Companion to the Barrington Atlas of the Greek and Roman World. CMCS. ISBN 978-0955718236.

- Gorrochategui, Joaquín (2011). "Linguistisque et peuplement en Aquitania". L’âge du Fer en Aquitaine et sur ses marges. Mobilité des hommes, diffusion des idées, circulation des biens dans l’espace européen à l’âge du Fer. Actes du 35e Colloque international de l’AFEAF.

- Matasović, Ranko (2009). Etymological Dictionary of Proto-Celtic. Brill. ISBN 9789004173361.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Nègre, Ernest (1990). Toponymie générale de la France (in French). Librairie Droz. ISBN 978-2-600-02883-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Spickermann, Wolfgang (2006). "Adiatunnus". Brill’s New Pauly.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Vennemann, Theo (2003). Europa Vasconica - Europa Semitica. Walter de Gruyter. ISBN 978-3-11-090570-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)