Caeroesi

The Caeroesi (also Caeraesi, Ceroesi, Cerosi) were a Belgic-Germanic tribe, living in Belgic Gaul when Julius Caesar's Roman forces entered the area in 57 BCE. They are known from his account of the Gallic War, and are generally also equated with the Caeracates mentioned briefly by Tacitus in his Histories.[1][2]

They were one of a group of tribes listed by his local informants as the Germani, along with the Eburones, Condrusi, Paemani (or Caemani), and Segni.[3] These tribes are referred to as the "Germani Cisrhenani", to distinguish them from Germani living on the east of the Rhine, outside of the Gaulish and Roman area.

Whether this meant that they actually spoke a Germanic language or not, is still uncertain,[4] but it was claimed by Tacitus that these Germani were the original Germani, and that the term Germani as it came to be widely used was not the original meaning. He also said that the descendants of the original Germani in his time were the Tungri.[5]

Name

Etymology

Both tribal names 'Caeroesi' and 'Caeracates' are generally considered to be Celtic.[6][7][2] They are probably linguistically related to the Brittonic Caereni and to the Pictish Kairènoi.[6][2]

The name 'Caeracates' most likely meant 'those of the sheep, sheep-folk', i.e. 'the shepherds'.[8][6][2] It stems from the Gaulish root *caerac- ('ewe' or a similar animal; compare with Old Irish caera gen. caerach 'ewe', and with Welsh caeriwrch 'roe deer') attached to the suffix -ates ('belonging to').[6][9][2]

The variant 'Caeroesi' has an unexplained suffix (-oeso-) which is not found in either Celtic or Germanic languages, although -oso- is a known suffix in Gaulish.[10][11] A Proto-Celtic root *caero- (< *capero) has thus been posited for the first element caer-, and compared with Latin caper or Old Norse hafr, 'billy goat'.[2] Caeroesi could have meant 'the sheep', 'the rams', or 'rich in sheep', although its exact translation remains uncertain.[6]

Alternative relations with the Old Irish cáera ('berry'),[12][10] or with the Middle Irish céar ('dark brown') have also been proposed.[9]

Toponymy

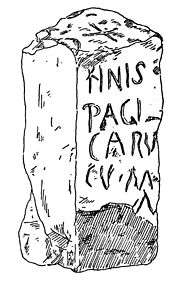

The region of pagus Carucum, a subdivision of the Treveri during the Roman period, later known under the Franks as Pagus Coroascus, may be named after the tribe,[8] although the linguistic connection is not regarded as certain by some scholars.[13]

The name has been discovered on a Roman era boundary marker, in a wooded area near Neidenbach bei Kyllburg, carved with the inscription 'FINIS PAGI CARV CVM' ('boundary or end of the pagus Carucum').[14]

To the east of Neidenbach, the Vinxtbach, a small river flowing eastwards to the Rhine, marked the boundary between the Roman provinces of Germania Superior and Germania Inferior. The name Vinxtbach is in fact thought to derive from the Latin word finis, meaning an end or boundary.

Today the Vinxtbach is still a boundary between modern German dialects, with Ripuarian to the north, and Moselle Frankish to the south. Also nearby is the modern boundary of modern German Länder of Rheinland-Pfalz and Nordrhein-Westfalen.

Geography

The general area of the Belgic Germani was between the Scheldt and Rhine rivers, and north of Luxemburg and the Moselle, which is where the Treverii lived. In modern terms this area includes eastern Belgium, the southern parts of the Netherlands, and a part of Germany on the west of the Rhine, but north of Koblenz.[15]

History

Tacitus mentioned the "Caeracates" in his Histories, in his description of the Batavian revolt. They were called with the Vangiones and the Triboci, to reinforce a Treveri force.[16]

References

- "Histories" 4.70.

- Delamarre 2003, p. 97.

- Julius Caesar, Commentarii de Bello Gallico 2.4 and 6.32

- von Petrikovits 1999, p. 99.

- Tacitus, Germania, II 2. ceterum Germaniae vocabulum recens et nuper additum, quoniamqui primi Rhenum transgressi Gallos expulerint ac nunc Tungri, tunc Germani vocati sint: ita nationis nomen, nongentis, evaluisse paulatim, ut omnes primum a victore obmetum, mox et a se ipsis invento nomine Germani vocarentur.

- Sergent 1991, pp. 10–11.

- Neumann 1999, pp. 110–111.

- Wightman 1985, p. 31.

- Neumann 1999, p. 110.

- Busse 2006, p. 199.

- Neumann 1999, p. 111.

- Neumann 1981, p. 309.

- von Petrikovits 1999, p. 93.

- Corpus Inscriptionum Latinarum XIII 4143

- Wightman 1985, p. 30.

- IV 70.

Bibliography

- Busse, Peter E. (2006). "Belgae". In Koch, John T. (ed.). Celtic Culture: A Historical Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. pp. 195–200. ISBN 978-1-85109-440-0.

- Delamarre, Xavier (2003). Dictionnaire de la langue gauloise: Une approche linguistique du vieux-celtique continental (in French). Errance. ISBN 9782877723695.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Neumann, Günter (1981), "Caeroesi", Reallexikon der Germanischen Altertumskunde (RGA), 4 (2 ed.), Berlin/New York: Walter de Gruyter, pp. 309–310, ISBN 3-11-006513-4CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Neumann, Günter (1999), "Germani cisrhenani — die Aussage der Namen", in Beck, H.; Geuenich, D.; Steuer, H. (eds.), Germanenprobleme in heutiger Sicht, Walter de Gruyter, ISBN 978-3110164381CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Sergent, Bernard (1991). "Ethnozoonymes indo-européens". Dialogues d'histoire ancienne. 17 (2). doi:10.3406/dha.1991.1932.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- von Petrikovits, Harald (1999), "Germani Cisrhenani", in Beck, H.; Geuenich, D.; Steuer, H. (eds.), Germanenprobleme in heutiger Sicht, Walter de Gruyter, ISBN 978-3110164381CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Wightman, Edith M. (1985). Gallia Belgica. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-05297-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)