Presidency of John F. Kennedy

The presidency of John F. Kennedy began at noon EST on January 20, 1961, when Kennedy was inaugurated as the 35th President of the United States, and ended on November 22, 1963, upon his assassination, a span of 1,036 days. A Democrat from Massachusetts, he took office following the 1960 presidential election, in which he narrowly defeated Richard Nixon, the then–incumbent Vice President. He was succeeded by Vice President Lyndon B. Johnson.

| |

| Presidency of John F. Kennedy | |

|---|---|

| January 20, 1961 – November 22, 1963 (Assassination) | |

| President | John F. Kennedy |

| Cabinet | See list |

| Party | Democratic |

| Election | 1960 |

| Seat | White House |

| |

| Seal of the President | |

| ||

|---|---|---|

President of the United States

Appointments

Assassination and legacy

|

||

Kennedy's time in office was marked by Cold War tensions with the Soviet Union and Cuba. In Cuba, a failed attempt was made in April 1961 at the Bay of Pigs to overthrow the government of Fidel Castro. In October 1962, the Kennedy administration learned that Soviet ballistic missiles had been deployed in Cuba; the resulting Cuban Missile Crisis nearly resulted in nuclear war, but ended when the Soviets withdrew the missiles. To contain Communist expansion in Asia, Kennedy increased the number of American military advisers in South Vietnam by a factor of 18; a further escalation of the American role in the Vietnam War would take place after Kennedy's death. In Latin America, Kennedy's Alliance for Progress aimed to promote human rights and foster economic development.

In domestic politics, Kennedy made bold proposals in his New Frontier agenda, but many of his initiatives were blocked by the conservative coalition of Northern Republicans and Southern Democrats. The failed initiatives include federal aid education, medical care for the aged, and aid to economically depressed areas. Though initially reluctant to pursue civil rights legislation, in 1963 Kennedy proposed a major civil rights bill that ultimately became the Civil Rights Act of 1964. The economy experienced steady growth, low inflation and a drop in unemployment rates during Kennedy's tenure. Kennedy adopted Keynesian economics and proposed a tax cut bill that was passed into law as the Revenue Act of 1964. Kennedy also established the Peace Corps and promised to land an American on the moon, thereby intensifying the Space Race with the Soviet Union.

Kennedy was assassinated on November 22, 1963 while visiting Dallas, Texas. The Warren Commission concluded that Lee Harvey Oswald acted alone in assassinating Kennedy, but the assassination gave rise to a wide array of conspiracy theories. Kennedy was the first Roman Catholic elected president, as well as the youngest candidate ever to win a U.S. presidential election. Historians and political scientists tend to rank Kennedy as an above-average president.

1960 election

Kennedy, who represented Massachusetts in the United States Senate from 1953 to 1960, had finished second on the vice presidential ballot of the 1956 Democratic National Convention. After Republican President Dwight D. Eisenhower defeated Adlai Stevenson II in the 1956 presidential election, Kennedy began to prepare a bid for the presidency in the 1960 election.[1] In January 1960, Kennedy formally announced his candidacy in that year's presidential election. Senator Hubert Humphrey of Minnesota emerged as Kennedy's primary challenger in the 1960 Democratic primaries,[2] but Kennedy's victory in the heavily-Protestant state of West Virginia prompted Humphrey's withdrawal from the race.[3] At the 1960 Democratic National Convention, Kennedy fended off challenges from Stevenson and Senator Lyndon B. Johnson of Texas to win the presidential nomination on the first ballot of the convention.[2] Kennedy chose Johnson to be his vice-presidential running mate, despite opposition from many liberal delegates and Kennedy's own staff, including his brother Robert F. Kennedy.[4] Kennedy believed that Johnson's presence on the ticket would appeal to Southern voters, and he thought that Johnson could serve as a valuable liaison to the Senate.[2]

Incumbent Vice President Richard Nixon faced little opposition for the 1960 Republican nomination. He easily won the party's primaries and received the nearly-unanimous backing of the delegates at the 1960 Republican National Convention. Nixon chose Henry Cabot Lodge, Jr., the chief U.S. delegate to the United Nations, as his running mate.[3] Both presidential nominees traveled extensively during the course of the campaign. Not wanting to concede any state as "unwinnable," Nixon undertook a fifty-state strategy, while Kennedy focused the states with the most electoral votes.[3] Ideologically, Kennedy and Nixon agreed on the continuation of the New Deal and the Cold War containment policy.[5] Major issues in the campaign included the economy, Kennedy's Catholicism, Cuba, and whether the Soviet space and missile programs had surpassed those of the U.S.[6]

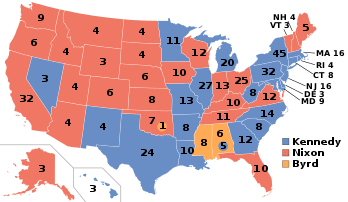

On November 8, 1960, Kennedy defeated Nixon in one of the closest presidential elections of the 20th century.[7] Kennedy won the popular vote by a narrow margin of 120,000 votes out of a record 68.8 million ballots cast.[3] He won the electoral vote by a wider margin, receiving 303 votes to Nixon's 219. 14 unpledged electors[lower-alpha 1] from two states—Alabama and Mississippi—voted for Senator Harry F. Byrd of Virginia, as did one faithless elector[lower-alpha 2] in Oklahoma.[7] In the concurrent congressional elections, Democrats retained wide majorities in both the House of Representatives and the Senate.[10] Kennedy was the first person born in the 20th century to be elected president,[11] and, at age 43, the youngest person elected to the office.[12][lower-alpha 3] He was also the first Roman Catholic elected to the presidency.[14]

Inauguration

Kennedy was inaugurated as the nation's 35th president on January 20, 1961, on the East Portico of the United States Capitol. Chief Justice Earl Warren administered the oath of office.[15] In his inaugural address, Kennedy spoke of the need for all Americans to be active citizens, famously saying: "Ask not what your country can do for you; ask what you can do for your country." He also invited the nations of the world to join together to fight what he called the "common enemies of man: tyranny, poverty, disease, and war itself."[16] To these admonitions he added:

All this will not be finished in the first one hundred days. Nor will it be finished in the first one thousand days, nor in the life of this Administration, nor even perhaps in our lifetime on this planet. But let us begin." In closing, he expanded on his desire for greater internationalism: "Finally, whether you are citizens of America or citizens of the world, ask of us here the same high standards of strength and sacrifice which we ask of you.[16]

The address reflected Kennedy's confidence that his administration would chart an historically significant course in both domestic policy and foreign affairs. The contrast between this optimistic vision and the pressures of managing daily political realities at home and abroad would be one of the main tensions running through the early years of his administration.[17] Full text ![]()

Administration

| The Kennedy Cabinet | ||

|---|---|---|

| Office | Name | Term |

| President | John F. Kennedy | 1961–1963 |

| Vice President | Lyndon B. Johnson | 1961–1963 |

| Secretary of State | Dean Rusk | 1961–1963 |

| Secretary of the Treasury | C. Douglas Dillon | 1961–1963 |

| Secretary of Defense | Robert McNamara | 1961–1963 |

| Attorney General | Robert F. Kennedy | 1961–1963 |

| Postmaster General | J. Edward Day | 1961–1963 |

| John A. Gronouski | 1963 | |

| Secretary of the Interior | Stewart Udall | 1961–1963 |

| Secretary of Agriculture | Orville Freeman | 1961–1963 |

| Secretary of Commerce | Luther H. Hodges | 1961–1963 |

| Secretary of Labor | Arthur Goldberg | 1961–1962 |

| W. Willard Wirtz | 1962–1963 | |

| Secretary of Health, Education, and Welfare | Abraham Ribicoff | 1961–1962 |

| Anthony J. Celebrezze | 1962–1963 | |

| Ambassador to the United Nations | Adlai Stevenson II | 1961–1963 |

Kennedy spent the eight weeks following his election choosing his cabinet, staff and top officials.[18] He retained J. Edgar Hoover as Director of the Federal Bureau of Investigation and Allen Dulles as Director of Central Intelligence. C. Douglas Dillon, a business-oriented Republican who had served as Eisenhower's Undersecretary of State, was selected as Secretary of the Treasury. Kennedy balanced the appointment of the relatively conservative Dillon by selecting liberal Democrats to hold two other important economic advisory posts; David E. Bell became the Director of the Bureau of the Budget, while Walter Heller served as the Chairman of the Council of Economic Advisers.[19]

Robert McNamara, who was well known as one of Ford Motor Company's "Whiz Kids", was appointed Secretary of Defense. Rejecting liberal pressure to choose Stevenson as Secretary of State, Kennedy instead turned to Dean Rusk, a restrained former Truman official, to lead the Department of State. Stevenson accepted a non-policy role as the ambassador to the United Nations.[19] In spite of concerns over nepotism, Kennedy's father insisted that Robert F. Kennedy become Attorney General, and the younger Kennedy became the "assistant president" who advised on all major issues.[20] McNamara and Dillon also emerged as important advisers from the cabinet.[21]

Kennedy scrapped the decision-making structure of Eisenhower,[22] preferring an organizational structure of a wheel with all the spokes leading to the president; he was ready and willing to make the increased number of quick decisions required in such an environment.[23] Though the cabinet remained an important body, Kennedy generally relied more on his staffers within the Executive Office of the President. Unlike Eisenhower, Kennedy did not have a chief of staff, but instead relied on a small number of senior aides, including appointments secretary Kenneth O'Donnell.[24] National Security Advisor McGeorge Bundy was the most important adviser on foreign policy, eclipsing Secretary of State Rusk.[25][26] Ted Sorensen was a key advisor on domestic issues who also wrote many of Kennedy's speeches.[27] Other important advisers and staffers included Larry O'Brien, Arthur M. Schlesinger Jr., press secretary Pierre Salinger, General Maxwell D. Taylor, and W. Averell Harriman.[28][29] Kennedy maintained cordial relations with Vice President Johnson, who was involved in issues like civil rights and space policy, but Johnson did not emerge as an especially influential vice president.[30]

Judicial appointments

Kennedy made two appointments to the United States Supreme Court. After the resignation of Charles Evans Whittaker in early 1962, President Kennedy assigned Attorney General Kennedy to conduct a search of potential successors, and the attorney general compiled a list consisting of Deputy Attorney General Byron White, Secretary of Labor Arthur Goldberg, federal appellate judge William H. Hastie, legal professor Paul A. Freund, and two state supreme court justices. Kennedy narrowed his choice down to Goldberg and White, and he ultimately chose the latter, who was quickly confirmed by the Senate. A second vacancy arose later in 1962 due to the retirement of Felix Frankfurter. Kennedy quickly appointed Goldberg, who easily won confirmation by the Senate. Goldberg resigned from the court in 1965 to accept appointment as ambassador to the United Nations, but White remained on the court until 1993, often serving as a key swing vote between liberal and conservative justices.[31] Due in part to the creation of new federal judgeships in 1961, Kennedy appointed 130 individuals to the federal courts. Among his appointments was Thurgood Marshall, who later joined the Supreme Court.[32]

Foreign affairs

The Cold War and flexible response

Kennedy's foreign policy was dominated by American confrontations with the Soviet Union, manifested by proxy contests in the global state of tension known as the Cold War. Like his predecessors, Kennedy adopted the policy of containment, which sought to stop the spread of Communism.[33] President Eisenhower's New Look policy had emphasized the use of nuclear weapons to deter the threat of Soviet aggression. Fearful of the possibility of a global nuclear war, Kennedy implemented a new strategy known as flexible response. This strategy relied on conventional arms to achieve limited goals. As part of this policy, Kennedy expanded the United States special operations forces, elite military units that could fight unconventionally in various conflicts. Kennedy hoped that the flexible response strategy would allow the U.S. to counter Soviet influence without resorting to war.[34] At the same time, he ordered a massive build-up of the nuclear arsenal to establish superiority over the Soviet Union.[33]

In pursuing this military build-up, Kennedy shifted away from Eisenhower's deep concern for budget deficits caused by military spending.[35] In contrast to Eisenhower’s warning about the perils of the military-industrial complex, Kennedy focused on rearmament. From 1961 to 1964 the number of nuclear weapons increased by 50 percent, as did the number of B-52 bombers to deliver them. The new ICBM force grew from 63 intercontinental ballistic missiles to 424. He authorized 23 new Polaris submarines, each of which carried 16 nuclear missiles. Meanwhile, he called on cities to prepare fallout shelters for nuclear war.[36]

Cuba and the Soviet Union

Bay of Pigs Invasion

Fulgencio Batista, a Cuban dictator friendly towards the United States, had been forced out office in 1959 by the Cuban Revolution. Many in the United States, including Kennedy himself, had initially hoped that Batista's successor, Fidel Castro would preside over democratic reforms. Dashing those hopes, by the end of 1960 Castro had embraced Marxism, confiscated American property, and accepted Soviet aid.[37] The Eisenhower administration had created a plan to overthrow Castro's regime though an invasion of Cuba by a counter-revolutionary insurgency composed of U.S.-trained, anti-Castro Cuban exiles[38][39] led by CIA paramilitary officers.[40] Kennedy had campaigned on a hard-line stance against Castro, and when presented with the plan that had been developed under the Eisenhower administration, he enthusiastically adopted it regardless of the risk inflaming tensions with the Soviet Union.[41] Some advisors, including Schlesinger, Under Secretary of State Chester Bowles, and former Secretary of State Dean Acheson, opposed the operation, but Bundy and McNamara both favored it, as did the Joint Chiefs of Staff, despite serious reservations.[42]

On April 17, 1961, Kennedy ordered the Bay of Pigs Invasion: 1,500 American-trained Cubans, called Brigade 2506, landed on the inlet of that name.[43] The goal was to spark a widespread popular uprising against Castro, but no such uprising occurred. [44] Although the Eisenhower administration plan had called for an American airstrikes to hold back the Cuban Counter attack until the invaders were established, Kennedy rejected the strike because it would emphasize the American sponsorship of the invasion.[45] CIA director Allen Dulles later stated that they thought the president would authorize any action required for success once the troops were on the ground.[43] By April 19, 1961, the Cuban government had captured or killed the invading exiles, and Kennedy was forced to negotiate for the release of the 1,189 survivors. After twenty months, Cuba released the captured exiles in exchange for a ransom of $53 million worth of food and medicine.[46]

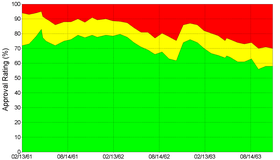

Despite the lack of direct U.S. military involvement, the Soviet Union, Cuba, and the international community all recognized that the U.S. had backed the invasion.[45] Kennedy focused primarily on the political repercussions of the plan rather than military considerations.[47] In the aftermath, he took full responsibility for the failure, saying: "We got a big kick in the leg and we deserved it. But maybe we'll learn something from it."[48] Kennedy's approval ratings climbed afterwards, helped in part by the vocal support given to him by Nixon and Eisenhower.[49] Outside the United States, however, the operation undermined Kennedy's reputation as a world leader, and raised tensions with the Soviet Union.[50] The Kennedy administration banned all Cuban imports, convinced the Organization of American States to expel Cuba, and turned to the CIA to plot the overthrow of Castro through its Cuban Project.[51] A secret review conducted by Lyman Kirkpatrick of the CIA concluded that the failure of the invasion resulted less from a decision against airstrikes and had more to do with the fact that Cuba had a much larger defending force and that the operation suffered from "poor planning, organization, staffing and management".[52] Kennedy dismissed Dulles as director of the CIA and increasingly relied on close advisers like Sorensen, Bundy, and Robert Kennedy as opposed to the Joint Chiefs of Staff, the CIA, and the State Department.[53]

Vienna Summit and the Berlin Wall

In the aftermath of the Bay of Pigs invasion, Kennedy announced that he would meet with Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev at the June 1961 Vienna summit. The summit would cover several topics, but both leaders knew that the most contentious issue would be that of Berlin, which had been divided into two cities with the start of the Cold War. The enclave of West Berlin lay within Soviet-allied East Germany, but was supported by the U.S. and other Western powers. The Soviets wanted to reunify Berlin under the control of East Germany, partly due to the large number of East Germans who had fled to West Berlin.[54] Khrushchev had clashed with Eisenhower over the issue but had tabled it after the 1960 U-2 incident; with the inauguration of a new U.S. president, Khrushchev was once again determined to bring the status of West Berlin to the fore. Kennedy's handling of the Bay of Pigs crisis convinced him that Kennedy would wither under pressure. Kennedy, meanwhile, wanted to meet with Khrushchev as soon as possible in order to reduce tensions and minimize the risk of nuclear war. Prior to summit, Harriman advised Kennedy, "[Khrushchev's] style will be to attack you and see if he can get away with it. Laugh about it, don't get into a fight. Rise above it. Have some fun."[55]

On June 4, 1961, the president met with Khrushchev in Vienna, where he made it clear that any treaty between East Berlin and the Soviet Union that interfered with U.S. access rights in West Berlin would be regarded as an act of war.[56] The two leaders also discussed the situation in Laos, the Congo Crisis, China's fledgling nuclear program, a potential nuclear test ban treaty, and other issues.[57] Shortly after Kennedy returned home, the Soviet Union announced its intention to sign a treaty with East Berlin that would threaten Western access to West Berlin. Kennedy, depressed and angry, assumed that his only option was to prepare the country for nuclear war, which he personally thought had a one-in-five chance of occurring.[56]

In the weeks immediately after the Vienna summit, more than 20,000 people fled from East Berlin to the western sector in reaction to statements from the USSR. Kennedy began intensive meetings on the Berlin issue, where Dean Acheson took the lead in recommending a military buildup alongside NATO allies.[58] In a July 1961 speech, Kennedy announced his decision to add $3.25 billion to the defense budget, along with over 200,000 additional troops, stating that an attack on West Berlin would be taken as an attack on the U.S.[59] Meanwhile, the Soviet Union and East Berlin began blocking further passage of East Berliners into West Berlin and erected barbed wire fences across the city, which were quickly upgraded to the Berlin Wall.[60] Kennedy acquiesced to the wall, though he sent Vice President Johnson to West Berlin to reaffirm U.S. commitment to the enclave's defense. In the following months, in a sign of rising Cold War tensions, both the U.S. and the Soviet Union ended a moratorium on nuclear weapon testing.[61]

Cuban Missile Crisis

In the aftermath of the Bay of Pigs and invasion Cuban and Soviet leaders feared that the United States was planning another invasion of Cuba, and Khrushchev increased economic and military assistance to the island.[62] The Kennedy administration viewed the growing Cuba-Soviet alliance with alarm, fearing that it could eventually pose a threat to the United States.[63] Kennedy did not believe that the Soviet Union would risk placing nuclear weapons in Cuba, but he dispatched CIA U-2 spy planes to determine the extent of the Soviet military build-up.[63] On October 14, 1962, the spy planes took photographs of intermediate-range ballistic missile sites being built in Cuba by the Soviets. The photos were shown to Kennedy on October 16, and a consensus was reached that the missiles were offensive in nature.[64]

Following the Vienna Summit, Khrushchev came to believe that Kennedy would not respond effectively to provocations. He saw the deployment of the missiles in Cuba as a way to close the "missile gap" and provide for the defense of Cuba. By late 1962, both the United States and the Soviet Union possessed intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs) capable of delivering nuclear payloads, but the U.S. maintained well over 100 ICBMs, as well as over 100 submarine-launched ballistic missile (SLBMs). By contrast, the Soviet Union did not possess SLBMs, and had less than 25 ICBMs. The placement of missiles in Cuba thus threatened to significantly enhance the Soviet Union's first strike capability and even the nuclear imbalance.[65] Kennedy himself did not believe that the deployment of missiles to Cuba fundamentally altered the strategic balance of the nuclear forces; more significant for him was the political and psychological implications of allowing the Soviet Union to maintain nuclear weapons in Cuba.[66]

Kennedy faced a dilemma: if the U.S. attacked the sites, it might lead to nuclear war with the U.S.S.R., but if the U.S. did nothing, it would appear weak. On a personal level, Kennedy needed to show resolve in reaction to Khrushchev, especially after the Vienna summit.[67] To deal with the crisis, he formed an ad hoc body of key advisers, later known as EXCOMM, that met secretly between October 16 and October 28.[68] The members of EXCOMM agreed that the missiles must be removed from Cuba, but differed as to the best method. Some favored an airstrike, possibly followed by an invasion of Cuba, but Robert Kennedy and others argued that a surprise airstrike would be immoral and would invite Soviet reprisals.[69] The other major option that emerged was a naval blockade, designed to prevent further arms shipments to Cuba. Though he had initially favored an immediate air strike, the president quickly came to favor the naval blockade the first method of response, while retaining the option of an airstrike at a later date.[70] EXCOMM voted 11-to-6 in favor of the naval blockade, which was also supported by British ambassador David Ormsby-Gore and Eisenhower, both of whom were consulted privately.[71] On October 22, after privately informing the cabinet and leading members of Congress about the situation, Kennedy announced on national television that the U.S. had discovered evidence of the Soviet deployment of missiles to Cuba. He called for the immediate withdrawal of the missiles, as well as the convening of the United Nations Security Council and the Organization of American States (OAS). Finally, he announced that the U.S. would begin a naval blockade of Cuba in order to intercept arms shipments.[72]

On October 23, in a unanimous vote, the OAS approved a resolution that endorsed the blockade and called for the removal of the Soviet nuclear weapons from Cuba. That same day, Stevenson presented the U.S. case to the UN Security Council, though the Soviet Union's veto power precluded the possibility of passing a Security Council resolution.[73] On the morning of October 24, over 150 U.S. ships were deployed to enforce the blockade against Cuba. Several Soviet ships approached the blockade line, but they stopped or reverse course to avoid the blockade.[74] On October 25, Khrushchev offered to remove the missiles if the U.S. promised not to invade Cuba. The next day, he sent a second message in which he also demanded the removal of Jupiter missiles from Turkey.[75] EXCOMM settled on what has been termed the "Trollope ploy;" the U.S. would respond to the Khrushchev's first message and ignore the second. On October 27, Kennedy sent a letter to Khrushchev calling for the removal of the Cuban missiles in return for an end to the blockade and an American promise to refrain from invading Cuba. At the president's direction, Robert Kennedy privately informed the Soviet ambassador that the U.S. would remove the missiles from Turkey after the end of the crisis.[76] Few members of EXCOMM expected Khrushchev to agree to the offer, but on October 28 Khrushchev publicly announced that he would withdraw the missiles from Cuba.[76] Negotiations over the details of the withdrawal continued, but the U.S. ended the naval blockade on November 20, and most Soviet soldiers left Cuba by early 1963.[77]

The U.S. publicly promised never to invade Cuba and privately agreed to remove its missiles in Italy and Turkey; the missiles were by then obsolete and had been supplanted by submarines equipped with UGM-27 Polaris missiles.[78] In the aftermath of the crisis, the United States and the Soviet Union established a hotline to ensure clear communications between the leaders of the two countries.[79] The Cuban Missile Crisis brought the world closer to nuclear war than at any point before or since. In the end, "the humanity" of the two men prevailed.[80] The crisis improved the image of American willpower and the president's credibility. Kennedy's approval rating increased from 66% to 77% immediately thereafter.[81] Kennedy's handling of the Cuban Missile Crisis has received wide praise from many scholars, although some critics fault the Kennedy administration for precipitating the crisis with its efforts to remove Castro.[82][83] Khrushchev, meanwhile, was widely mocked for his performance, and was removed from power in October 1964.[84]

Nuclear Test Ban Treaty

Troubled by the long-term dangers of radioactive contamination and nuclear weapons proliferation, Kennedy and Khrushchev agreed to negotiate a nuclear test ban treaty, originally conceived in Adlai Stevenson's 1956 presidential campaign.[85] In their Vienna summit meeting in June 1961, Khrushchev and Kennedy had reached an informal understanding against nuclear testing, but further negotiations were derailed by the resumption of nuclear testing.[86] Soviet-American relations improved after the resolution of the Cuban Missile Crisis, and the powers resumed negotiations over a test ban treaty.[87]

On June 10, 1963, Kennedy delivered a commencement address at the American University in Washington, D.C., in which he announced that the Soviet had agreed to resume nuclear test ban treaty talks. He and also announced, for the purpose of showing "good faith and solemn convictions", his decision to postpone planned atmospheric nuclear weapons tests, and pledged that the U.S. would refrain from conducting further tests as long as all other nations would do the same.[88] The U.S., Kennedy commented, was seeking a goal of "complete disarmament" of nuclear weapons, and he vowed that America "will never start a war".[89]

The following month, Kennedy sent W. Averell Harriman to Moscow to negotiate a test-ban treaty with the Soviets.[90] Each party sought a comprehensive test ban treaty, but a dispute over the number of on-site inspections allowed in each year prevented a total ban on testing.[87] Ultimately, the United States, the United Kingdom, and the Soviet Union agreed to a limited treaty that prohibited atomic testing on the ground, in the atmosphere, or underwater, but not underground.[91] The treaty represented an important deescalation of Cold War tensions, but both countries continued to build their respective nuclear stockpiles.[92] The U.S. and the Soviet Union also reached an agreement whereby the U.S. sold millions of bushels of wheat to the Soviet Union.[93]

Southeast Asia

Laos

When briefing Kennedy, Eisenhower emphasized that the communist threat in Southeast Asia required priority. Eisenhower considered Laos to be "the cork in the bottle;" if it fell to Communism, Eisenhower believed other Southeast Asian would, as well.[94] The Joint Chiefs proposed sending 60,000 American soldiers to uphold the friendly government, but Kennedy rejected this strategy in the aftermath of the failed Bay of Pigs invasion. He instead sought a negotiated solution between the government and the left-wing insurgents, who were backed by North Vietnam and the Soviet Union.[95] Kennedy was unwilling to send more than a token force to neighboring Thailand, a key American ally. By the end of the year, Harriman had helped arrange the International Agreement on the Neutrality of Laos, which temporarily brought an end to the crisis, but the Laotian Civil War continued.[96] Though he was unwilling to commit U.S. forces to a major military intervention in Laos, Kennedy did approve CIA activities in Laos designed to defeat Communist insurgents through bombing raids and the recruitment of the Hmong people.[97]

Vietnam

During his presidency, Kennedy continued policies that provided political, economic, and military support to the South Vietnamese government.[98] Vietnam had been divided into a communist North Vietnam and a non-Communist South Vietnam after the 1954 Geneva Conference, but North Vietnamese leader Ho Chi Minh established the Viet Cong in 1960 to foment support for unification in South Vietnam. The president of South Vietnam, Ngo Dinh Diem, had alienated many of his constituents by avoiding land reforms, refusing to hold free elections, and staging an anti-Communist purge. Kennedy escalated American involvement in Vietnam in 1961 by financing the South Vietnam army, increasing the number of U.S. military advisers above the levels of the Eisenhower administration, and authorizing U.S. helicopter units to provide support to South Vietnamese forces.[99]

Though Kennedy provided support for South Vietnam throughout his tenure, Vietnam remained a secondary issue for the Kennedy administration until 1963.[100] Kennedy increasingly soured on Diem, whose violent crackdown on Buddhist practices further galvanized opposition to his leadership. In August 1963, Henry Cabot Lodge, Jr. replaced Frederick Nolting as the U.S. ambassador to South Vietnam. Days after his arrival in South Vietnam, Lodge reported that several South Vietnamese generals sought the assent of the U.S. government to their plan of removing Diem from power. The Kennedy administration was split regarding not just the removal of Diem, but also their assessment of the military situation in South Vietnam and the proper U.S. role in the country. Without the full support of the U.S., General Dương Văn Minh (known as "Big Minh") called off the potential coup in South Vietnam. Big Minh again approached the U.S. about a coup, and administration official informed him that the U.S. would neither support or oppose the toppling of Diem. In November 1963, a junta of senior military officers executed Diem and his influential brother, Ngô Đình Nhu.[101]

By November 1963, there were 16,000 American military personnel in South Vietnam, up from Eisenhower's 900 advisors.[102] In the aftermath of the aborted coup in September 1963, the Kennedy administration reevaluated its policies in South Vietnam. Kennedy rejected both the full-scale deployment of ground soldiers, but also rejected the total withdrawal of U.S. forces from the country.[103] Historians disagree on whether the U.S. military presence in Vietnam would have escalated had Kennedy survived and been re-elected in 1964.[104] Fueling the debate are statements made by Secretary of Defense McNamara in the film "The Fog of War" that Kennedy was strongly considering pulling out of Vietnam after the 1964 election.[105] The film also contains a tape recording of Lyndon Johnson stating that Kennedy was planning to withdraw, a position that Johnson disagreed with.[106] Kennedy had signed National Security Action Memorandum (NSAM) 263, dated October 11, which ordered the withdrawal of 1,000 military personnel by the end of the year.[107][108] Such an action would have been a policy reversal, but Kennedy was moving in a less hawkish direction since his acclaimed speech about world peace at American University on June 10, 1963.[109]

Latin America

Kennedy sought to contain the threat of communism in Latin America by establishing the Alliance for Progress, which sent aid to some countries and sought greater human rights standards in the region.[110] The Alliance for Progress drew from the Good Neighbor Policy in its peaceful engagement with Latin America, and from the Marshall Plan in its expansion of aid and economic relationships. Kennedy also emphasized close personal relations with Latin American leaders, frequently hosting them in the White House.[111] The U.S. Information Agency was given an important role of reaching out to Latin Americans in Spanish, Portuguese, and French media.[112] The goals of the Alliance for Progress included long-term permanent improvement in living conditions through the advancement of industrialization, the improvement of communications systems, the reduction of trade barriers, and an increase in the number and diversity of exports from Latin America. At a theoretical level, Kennedy’s planners hoped to reverse the under-development of the region and its dependency on North America. Part of the administration's motivation was the fear that Castro’s Cuba would introduce anti-American political and economic changes if development did not take place.[113][114]

The U.S. also continued to use covert means in order to reduce Soviet influence. When Kennedy took office, the CIA had begun formulating plans for the assassination of Rafael Trujillo in the Dominican Republic. Kennedy privately instructed the CIA that any such planning must include plausible deniability by the U.S.[115] The administration had no role in Trujillo's assassination in 1961, but supported the government of Trujillo's successor, Juan Bosch. The United States launched a covert intervention in British Guiana to deny the left-wing leader Cheddi Jagan power in an independent Guyana, and forced a reluctant Britain to participate.[116] The CIA also engaged in operations in Brazil and Chile against left-wing leaders.[117]

Middle East

Iraq

Relations between the United States and Iraq became strained following the overthrow of the Iraqi monarchy on July 14, 1958, which resulted in the declaration of a republican government led by Brigadier Abd al-Karim Qasim.[118] On June 25, 1961, Qasim mobilized troops along the border between Iraq and Kuwait, declaring the latter nation "an indivisible part of Iraq" and causing a short-lived "Kuwait Crisis". The United Kingdom—which had just granted Kuwait independence on June 19, and whose economy was heavily dependent on Kuwaiti oil—responded on July 1 by dispatching 5,000 troops to the country to deter an Iraqi invasion. At the same time, Kennedy dispatched a U.S. Navy task force to Bahrain, and the U.K. (at the urging of the Kennedy administration) brought the dispute to United Nations Security Council, where the proposed resolution was vetoed by the Soviet Union. The situation was resolved in October, when the British troops were withdrawn and replaced by a 4,000-strong Arab League force.[119]

In December 1961, Qasim's government passed Public Law 80, which restricted the British- and American-owned Iraq Petroleum Company (IPC)'s concessionary holding to those areas in which oil was actually being produced, effectively expropriating 99.5% of the IPC concession. U.S. officials were alarmed by the expropriation as well as the recent Soviet veto of an Egyptian-sponsored UN resolution requesting the admittance of Kuwait as UN member state, which they believed to be connected. Senior National Security Council adviser Robert Komer worried that if the IPC ceased production in response, Qasim might "grab Kuwait" (thus achieving a "stranglehold" on Middle Eastern oil production), or "throw himself into Russian arms." Komer also made note of widespread rumors that a nationalist coup against Qasim could be imminent, and had the potential to "get Iraq back on [a] more neutral keel."[120]

The anti-imperialist and anti-communist Iraqi Ba'ath Party overthrew and executed Qasim in a violent coup on February 8, 1963. While there have been persistent rumors that the CIA orchestrated the coup, declassified documents and the testimony of former CIA officers indicate that there was no direct American involvement, although the CIA was actively seeking a suitable replacement for Qasim within the Iraqi military and had been informed of an earlier Ba'athist coup plot.[121] The Kennedy administration was pleased with the outcome and ultimately approved a $55 million arms deal for Iraq.[122]

Israel

President Kennedy ended the arms embargo that the Eisenhower and Truman administrations had enforced on Israel in favor of increased security ties, becoming the founder of the U.S.-Israeli military alliance. Describing the protection of Israel as a moral and national commitment, he was the first to introduce the concept of a 'special relationship' between the U.S. and Israel.[123] In 1962, the Kennedy administration sold Israel a major weapon system, the Hawk antiaircraft missile. Historians differ as to whether Kennedy pursued security ties with Israel primarily to shore up support with Jewish-American voters, or because of his admiration of the Jewish state.[124]

Kennedy warned the Israeli government against the production of nuclear materials in Dimona, which he believed could instigate a nuclear arms-race in the Middle East. After the existence of a nuclear plant was initially denied by the Israeli government, David Ben-Gurion stated in a speech to the Israeli Knesset on December 21, 1960, that the purpose of the nuclear plant at Beersheba was for "research in problems of arid zones and desert flora and fauna."[125] When Ben-Gurion met with Kennedy in New York, he claimed that Dimona was being developed to provide nuclear power for desalinization and other peaceful purposes "for the time being."[125] In 1962, the US and Israeli governments agreed to an annual inspection regime.[126] Despite these inspection, Rodger Davies, the director of the State Department's Office of Near Eastern Affairs, concluded in March 1965 that Israel was developing nuclear weapons. He reported that Israel's target date for achieving nuclear capability was 1968–1969.[127]

Decolonization and developing countries

.jpg)

Between 1960 and 1963, twenty-four countries gained independence as the process of decolonization continued. Many of these nations sought to avoid close alignment with either the United States or the Soviet Union, and in 1961, the leaders of India, Yugoslavia, Indonesia, Egypt, and Ghana created the Non-Aligned Movement. Kennedy set out to woo the leaders and people of the Third World, expanding economic aid and appointing knowledgeable ambassadors.[128] His administration established the Food for Peace program and the Peace Corps to provide aid to developing countries in various ways. The Food for Peace program became a central element in American foreign policy, and eventually helped many countries to develop their economies and become commercial import customers.[129]

Having chaired a subcommittee on Africa of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, Kennedy had developed a special interest in Africa. During the election campaign, Kennedy managed to mention Africa nearly 500 times, often attacking the Eisenhower administration for losing ground on that continent.[130] Kennedy considered the Congo Crisis to be one of the most important foreign policy issues facing his presidency, and he supported a UN operation that prevented the secession of the State of Katanga.[131] Kennedy also sought closer relations with Indian Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru through increased economic and a tilt away from Pakistan, but made little progress in bringing India closer to the United States.[132] Kennedy hoped to minimize Soviet influence in Egypt through good relations with President Gamal Abdel Nasser, but Nasser's hostility towards Saudi Arabia and Jordan closed off the possibility of closer relations.[133] In Southeast Asia, Kennedy helped mediate the West New Guinea dispute, convincing Indonesia and the Netherlands to agree to a plebiscite to determine the status of Dutch New Guinea.[134]

List of international trips

Kennedy made eight international trips during his presidency.[135]

| # | Dates | Country | Locations | Key highlights |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | May 16–18, 1961 | Ottawa | State visit. Met with Governor General Georges Vanier and Prime Minister John Diefenbaker. Addressed parliament. | |

| 2 | May 31 – June 3, 1961 | Paris | State visit. Addressed North Atlantic Council. Met with President Charles de Gaulle. | |

| June 3–4, 1961 | Vienna | Met with President Adolf Schärf. held talks with Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev. | ||

| June 4–5, 1961 | London | Private visit. Met with Queen Elizabeth II and Prime Minister Harold Macmillan. | ||

| 3 | December 16–17, 1961 | Caracas | Met with President Rómulo Betancourt. | |

| December 17, 1961 | Bogotá | Met with President Alberto Lleras Camargo. | ||

| 4 | December 21–22, 1961 | Hamilton | Met with Prime Minister Harold Macmillan. | |

| 5 | June 29 – July 1, 1962 | Mexico, D.F. | State visit. Met with President Adolfo López Mateos. | |

| 6 | December 18–21, 1962 | Nassau | Conferred with Prime Minister Harold Macmillan. Concluded Nassau Agreement on nuclear defense systems. | |

| 7 | March 18–20, 1963 | San José | Attended Conference of Presidents of the Central American Republics. | |

| 8 | June 23–25, 1963 | Bonn, Cologne, Frankfurt, Wiesbaden |

Met with Chancellor Konrad Adenauer and other officials. | |

| June 26, 1963 | West Berlin | Delivered several public addresses, including "Ich bin ein Berliner" speech. | ||

| June 26–29, 1963 | Dublin, Wexford, Cork, Galway, Limerick |

Addressed Oireachtas (parliament). Visited ancestral home.[136] | ||

| June 29–30, 1963 | Birch Grove | Informal visit with Prime Minister Harold Macmillan at his home. | ||

| July 1–2, 1963 | Rome, Naples |

Met with President Antonio Segni, Italian and NATO officials. | ||

| July 2, 1963 | Apostolic Palace | Audience with the newly elected Pope Paul VI. |

Domestic affairs

New Frontier

.jpg)

Kennedy called his domestic program the "New Frontier"; it included initiatives such as medical care for the elderly, federal aid to education, and the creation of a department of housing and urban development.[137] His New Frontier program was strongly influenced by Franklin D. Roosevelt's 1944 "Second Bill of Rights" address, as well as Harry Truman's Fair Deal.[138] Kennedy also called for a large tax cut as an economic stimulus measure. However, many of his programs were blocked by the conservative coalition of Republicans and southern Democrats.[137] The conservative coalition, which controlled key congressional committees and made up a majority of both houses of Congress during Kennedy's presidency, had prevented the implementation of progressive reforms since the late 1930s.[139] Kennedy's small margin of victory in the 1960 election, his lack of deep connections to influential members of Congress, and his administration's focus on foreign policy also hindered the passage of New Frontier policies.[140] Passage of the New Frontier was made even more difficult after the death of Speaker of the House Sam Rayburn; new Speaker John William McCormack and Senate Majority Leader Mike Mansfield both lacked the influence of their predecessors and struggled to exercise effective leadership over committee chairs.[141]

In 1961, Kennedy prioritized passing five bills: federal assistance for education, medical insurance for the elderly, housing legislation, federal aid to struggling areas, and an increase in the federal minimum wage.[138] Kennedy's bill to increase the federal minimum wage to $1.25 an hour passed in early 1961, but an amendment inserted by the staunch segregationist Congressman from Georgia, Carl Vinson, exempted hundreds of thousands of laundry workers (a job reserved for African-American women at the time) from the law.[142] Kennedy also won passage of the Area Redevelopment Act and the Housing Act of 1961. The Area Redevelopment Act provided federal funding to economically struggling regions of the country, while the Housing Act of 1961 provided funds for urban renewal and public housing and authorized federal mortgage loans to those who did not qualify for public housing.[143] Kennedy proposed a bill providing for $2.3 billion in federal educational aid to the states, with more money going to states with lower per-capita income. Though the Senate passed the education bill, it was defeated in the House by a coalition of Republicans, Southern Democrats, and Catholics.[144] Kennedy's health insurance bill, which would have paid for hospitalization and nursing costs for the elderly, failed to pass either house of Congress due to the opposition of Republicans, Southern Democrats, and the American Medical Association.[145] A bill that would have established the Department of Urban Affairs and Housing was also defeated.[146]

In 1962 and 1963, Kennedy won approval of the Manpower Development and Training Act, designed to provide job retraining, as well as bills that increased the regulation of drug manufacturers and authorized grants and loans for the construction of higher education facilities. Another Kennedy policy, the 1962 Trade Expansion Act, gave the president the power to cut tariffs and to take action against countries employing discriminatory tariffs.[147] Following the passage of that act, the U.S. and other countries agreed to major cuts in tariffs in the Kennedy Round.[148] Congress also passed the Community Mental Health Act, providing funding to local mental health community centers. These centers provided out-patient services such as marriage counseling and aid to those suffering from alcoholism.[149] In 1963, Kennedy began to focus more on the issue of poverty, and some of the ideas developed during his presidency would later influence President Johnson's War on Poverty.[150]

Peace Corps

An agency to enable Americans to volunteer in developing countries appealed to Kennedy because it fit in with his campaign themes of self-sacrifice and volunteerism, while also providing a way to redefine American relations with the Third World.[151] Upon taking office, Kennedy issued an executive order establishing the Peace Corps, and he named his brother-in-law, Sargent Shriver, as the agency's first director. Due in large part to Shriver's effective lobbying efforts, Congress approved the permanent establishment of the Peace Corps programs. Kennedy took great pride in the Peace Corps, and he ensured that it remained free of CIA influence, but he largely left its administration to Shriver. In the ensuing twenty-five years, more than 100,000 Americans served in 44 countries as part of the program. Most Peace Corps volunteers taught English in schools, but many became involved in activities like construction and food delivery.[152]

Economy

| Year | Income | Outlays | Surplus/ deficit |

GDP | Debt as a % of GDP[154] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1961 | 94.4 | 97.8 | -3.3 | 547.6 | 43.5 |

| 1962 | 99.7 | 106.8 | -7.1 | 586.9 | 42.3 |

| 1963 | 106.6 | 111.3 | -4.8 | 619.3 | 41.0 |

| 1964 | 112.6 | 118.5 | -5.9 | 662.9 | 38.7 |

| Ref. | [155] | [156] | [157] | ||

The economy, which had been through two recessions in three years, and was in one when Kennedy took office, accelerated notably during his presidency. Despite low inflation and interest rates, GDP had grown by an average of only 2.2% per annum during the Eisenhower presidency (scarcely more than population growth at the time), and had declined by 1% during Eisenhower's last twelve months in office.[158] GDP expanded by an average of 5.5% from early 1961 to late 1963,[158] inflation remained steady at around 1%,[159] and unemployment dropped from nearly 7 percent in January 1961 to 5.5 percent in December 1963.[160] Industrial production rose by 15% and motor vehicle sales rose by 40%.[161] This sustained rate of growth in GDP and industry continued until around 1969.[158] Kennedy was the first president to fully endorse Keynesian economics, which emphasized the importance of economic growth as opposed to inflation or deficits.[162][163] He ended a period of tight fiscal policies, loosening monetary policy to keep interest rates down and to encourage growth of the economy.[164] He presided over the first government budget to top the $100 billion mark, in 1962, and his first budget in 1961 led to the country's first non-war, non-recession deficit.[165]

In 1962, as the economy continued to grow, Kennedy became concerned with the issue of inflation. He asked companies and unions to work together to keep prices low, and met initial success.[166] He implemented guideposts developed by the Council of Economic Advisers that were designed to avoid wage-price spirals in key industries such as steel and automobiles. Kennedy was proud that his Labor Department help keep wages steady in the steel industry, but was outraged in April 1962, Roger Blough, the president of U.S. Steel, quietly informed Kennedy that his company would raise prices.[167] In response, Attorney General Robert Kennedy began a price-fixing investigation against U.S. Steel, and President Kennedy convinced other steel companies to rescind their price increases until finally even U.S. Steel, isolated and in danger of being undersold, agreed to rescind its own price increase.[168][169] Aside from his conflict with U.S. Steel, Kennedy generally maintained good relations with corporate leaders compared to his Democratic predecessors Truman and FDR, and his administration did not escalate the enforcement of antitrust law.[170] His administration also implemented new tax policies designed to encourage business investment.[171]

Walter Heller, who served as the chairman of the CEA, advocated for a Keynesian-style tax cut designed to help spur economic growth, and Kennedy adopted this policy.[172] The idea was that a tax cut would stimulate consumer demand, which in turn would lead to higher economic growth, lower unemployment, and increased federal revenues.[173] To the disappointment of liberals like John Kenneth Galbraith, Kennedy's embrace of the tax cut also shifted his administration's focus away from the proposed old-age health insurance program and other domestic expenditures.[174] In January 1963, Kennedy presented Congress with a tax cut that would reduce the top marginal tax rate from 91 percent to 65 percent, and lower the corporate tax rate from 52 percent to 47 percent. The predictions according to the Keynesian model indicated the cuts would decrease income taxes by about $10 billion and corporate taxes by about $3.5 billion. The plan also included reforms designed to reduce the impact of itemized deductions, as well as provisions to help the elderly and handicapped. Republicans and many Southern Democrats opposed the bill, calling for simultaneous reductions in expenditures, but debate continued throughout 1963.[175] In February 1964, three months Into Johnson's administration, Congress approved the Revenue Act of 1964, which lowered the top individual rate to 70 percent, and the top corporate rate to 48 percent.[176]

Civil rights

Early presidency

The turbulent end of state-sanctioned racial discrimination was one of the most pressing domestic issues of the 1960s. Jim Crow segregation had been established law in the Deep South for much of the 20th century,[177] but the Supreme Court of the United States had ruled in 1954 in Brown v. Board of Education that racial segregation in public schools was unconstitutional. Many schools, especially in southern states, did not obey the Supreme Court's decision. Kennedy favored desegregation and other civil rights causes, but he generally did not place a high priority on civil rights, especially before 1963.[178] Recognizing that conservative Southern Democrats could block legislation, Kennedy did not introduce civil rights legislation upon taking office.[179] Kennedy did appoint many blacks to office, including civil rights attorney Thurgood Marshall.[180] Kennedy also established the President's Committee on Equal Employment Opportunity to investigate employment discrimination and expanded the Justice Department's involvement in voting rights cases.[178]

Kennedy believed the grassroots movement for civil rights would anger many Southern whites and make it more difficult to pass civil rights laws in Congress, and he distanced himself from it.[181] As articulated by brother Robert, the administration's early priority was to "keep the president out of this civil rights mess."[180] Civil rights movement participants, mainly those on the front line in the South, viewed Kennedy as lukewarm,[180] especially concerning the Freedom Riders. The Freedom Riders organized an integrated public transportation effort in the South and were repeatedly met with white mob violence.[180] Robert Kennedy, speaking for the president, urged the Freedom Riders to "get off the buses and leave the matter to peaceful settlement in the courts."[182] Kennedy feared sending federal troops would stir up "hated memories of Reconstruction" among conservative Southern whites.[180] Displeased with Kennedy's pace addressing the issue of segregation, Martin Luther King, Jr. and his associates produced a document in 1962 calling on the president to follow in the footsteps of Abraham Lincoln and use an executive order to deliver a blow for civil rights as a kind of "Second Emancipation Proclamation."[183]

In September 1962, James Meredith enrolled at the University of Mississippi but was prevented from entering. Attorney General Robert Kennedy responded by sending 400 federal marshals, while President Kennedy reluctantly sent 3,000 troops after the situation on campus turned violent.[184] The Ole Miss riot of 1962 left two dead and dozens injured, but Meredith did finally enroll in his first class. Kennedy regretted not sending in troops earlier and he began to doubt whether the "evils of Reconstruction" he had been taught or believed were true.[180] On November 20, 1962, Kennedy signed Executive Order 11063, prohibiting racial discrimination in federally supported housing or "related facilities".[185]

Abolition of the poll tax

Sensitive to criticisms of the administration's commitment to protecting the constitutional rights of minorities at the ballot box, Attorney General Robert Kennedy, early in 1962, urged the president to press Congress to take action. Rather than proposing comprehensive legislation, President Kennedy put his support behind a proposed constitutional amendment that would prohibit states from conditioning the right to vote in federal elections on payment of a poll tax or other types of tax. He considered the constitutional amendment the best way to avoid a filibuster, as the claim that federal abolition of the poll tax was unconstitutional would be moot. Still, some liberals opposed Kennedy's action, feeling that an amendment would be too slow compared to legislation.[186] The poll tax was one of several laws that had been enacted by states across the South to disenfranchise and marginalize black citizens from politics so far as practicable without violating the Fifteenth Amendment.[187] Several civil rights groups[lower-alpha 4] opposed the proposed amendment on the grounds that it "would provide an immutable precedent for shunting all further civil rights legislation to the amendment procedure."[188] The amendment was passed by both houses of Congress in August 1962, and sent to the states for ratification. It was ratified on January 23, 1964, by the requisite number of states (38), becoming the Twenty-fourth Amendment to the United States Constitution.[189]

1963

Disturbed by the violent reaction to the civil rights campaign in Birmingham, and eager to prevent further violence or damage to U.S. foreign relations, Kennedy took a more active stance on civil rights in 1963.[190] On June 11, 1963, President Kennedy intervened when Alabama Governor George Wallace blocked the doorway to the University of Alabama to stop two African American students, Vivian Malone and James Hood, from attending. Wallace moved aside only after being confronted by Deputy Attorney General Nicholas Katzenbach and the Alabama National Guard, which had just been federalized by order of the president. That evening Kennedy delivered a major address on civil rights on national television and radio. In it he launched his initiative for civil rights legislation that would guarantee equal access to public schools and other facilities, the equal administration of justice, and also provide greater protection of voting rights.[191][192] Kennedy's embrace of civil rights causes would cost him in the South; Gallup polls taken in September 1963 would show his approval rating at 44 percent in the South, compared to a national approval rating of 62 percent.[193] As the president had predicted, the day after his civil rights address, and in reaction to it, House Majority leader Carl Albert called to advise him that his effort to extend the Area Redevelopment Act had been defeated, primarily by the votes of Southern Democrats and Republicans.[194]

A crowd of over one hundred thousand, predominantly African Americans, gathered in Washington for the civil rights March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom on August 28, 1963. Kennedy initially opposed the march, fearing it would have a negative effect on the prospects for the civil rights bills pending in Congress. These fears were heightened just prior to the march when FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover presented the administration with allegations that some of civil rights leader Martin Luther King Jr.'s close advisers, specifically Jack O'Dell and Stanley Levison, were communists.[195] When King ignored the administration's warning, Robert Kennedy issued a directive authorizing the FBI to wiretap King and other leaders of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference.[196] Although Kennedy only gave written approval for limited wiretapping of King's phones "on a trial basis, for a month or so",[197] Hoover extended the clearance so his men were "unshackled" to look for evidence in any areas of King's life they deemed worthy.[198] The wiretapping continued through June 1966 and was revealed in 1968.[199]

The task of coordinating the federal government's involvement in the August 28 March on Washington was given to the Department of Justice, which channeled several hundreds thousand dollars to the six sponsors of the March, including the NAACP and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference.[200] To ensure a peaceful demonstration, the organizers and the president personally edited speeches that were inflammatory and collaborated on all aspects related to times and venues. Thousands of troops were placed on standby. Kennedy watched King's speech on TV and was very impressed. The March was considered a "triumph of managed protest", and not one arrest relating to the demonstration occurred. Afterwards, the March leaders accepted an invitation to the White House to meet with Kennedy and photos were taken. Kennedy felt that the March was a victory for him as well and bolstered the chances for his civil rights bill.[200]

Notwithstanding the success of the March, the larger struggle was far from over. Three weeks later, a bomb exploded on Sunday, September 15 at the 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham; by the end of the day, four African American children had died in the explosion, and two other children shot to death in the aftermath.[201] Due to this resurgent violence, the civil rights legislation underwent some drastic amendments that critically endangered any prospects for its passage. An outraged president called congressional leaders to the White House and by the following day the original bill, without the additions, had enough votes to get it out of the House committee.[202] Gaining Republican support, Senator Everett Dirksen promised the legislation would be brought to a vote, preventing a Senate filibuster.[203] The following summer, on July 2, the guarantees Kennedy proposed in his June 1963 speech became federal law, when President Johnson signed the Civil Rights Act of 1964.[203]

Space policy

In the aftermath of the Soviet launch of Sputnik 1, the first artificial Earth satellite, NASA had proposed a manned lunar landing by the early 1970s.[204] Funding for the manned program, known as the Apollo program, was far from certain as Eisenhower held an ambivalent attitude on manned spaceflight.[205] Early in his presidency, Kennedy was poised to dismantle the manned space program, but he postponed any decision out of deference to Johnson, who had been a strong supporter of the space program in the Senate.[206] Along with Jerome Wiesner, Johnson was given a major role in overseeing the administration's space policy, and at Johnson's recommendation Kennedy appointed James E. Webb to head NASA.[207] In April 1961, Soviet cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin became the first person to fly in space, reinforcing American fears about being left behind in a technological competition with the Soviet Union.[208] Less than a month later, Alan Shepard became the first American to travel into space, strengthening Kennedy's confidence in NASA.[209]

In the aftermath of the Gagarin's flight, as well as the failed Bay of Pigs invasion, Kennedy felt pressured to respond to the perceived erosion of American prestige. He asked Johnson to explore the feasibility of beating the Soviets to the Moon. Though he was concerned about the program's costs, Kennedy agreed to Johnson's recommendation that the U.S. commit to a manned lunar landing as the major objective of the U.S. space program. In a May 25 speech, Kennedy declared,[209]

... I believe that this nation should commit itself to achieving the goal, before this decade is out, of landing a man on the Moon and returning him safely to the Earth. No single space project in this period will be more impressive to mankind, or more important for the long-range exploration of space; and none will be so difficult or expensive to accomplish.[210] Full text

Though Gallup polling showed that many in the public were skeptical of the necessity of the Apollo Program, members of Congress were strongly supportive in 1961, and they approved a major increase in NASA's funding. In 1962, John Glenn became the first American to orbit the Earth, and the following year Mariner program sent an unmanned flight past Venus. Though some members of Congress came to favor shifting NASA's budget to other programs, Kennedy and Johnson remained committed to the lunar landing. On July 20, 1969, two American astronauts landed on the Moon.[211]

Other issues

Status of women

During the 1960 presidential campaign, Kennedy endorsed the concept of equal pay for equal work, as well as the adoption of an Equal Rights Amendment.[212] His key appointee on women's issues was Esther Peterson, the Director of the United States Women's Bureau, who focused on improving the economic status of women.[213] In December 1961, Kennedy signed an executive order creating the Presidential Commission on the Status of Women to advise him on issues concerning the status of women.[214] Former First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt led the commission until her death in 1962. The commission's final report, entitled "American Women", was issued in October 1963. The report documented the legal and cultural discrimination women in America faced and made several policy recommendations to bring about change.[215] The creation of this commission, as well its prominent public profile, prompted Congress to begin considering various bills related to women's status. Among them was the Equal Pay Act of 1963, an amendment to the Fair Labor Standards Act, aimed at abolishing wage disparity based on sex; Kennedy signed it into law on June 10, 1963.[216] Kennedy also signed an executive order banning sex discrimination in the federal workforce.[217]

Organized crime

The issue of organized crime had gained national attention during the 1950s due in part to the investigations of the McClellan Committee. Both Robert Kennedy and John F. Kennedy had played a role on that committee, and in 1960 Robert Kennedy published the book The Enemy Within, which focused on the influence of organized crime within businesses and organized labor.[218] Under the leadership of the attorney general, the Kennedy administration shifted the focus of the Justice Department, the FBI, and the Internal Revenue Service to organized crime. Kennedy also won congressional approval for five bills designed to crack down on interstate racketeering, gambling, and the transportation of firearms. The federal government targeted prominent Mafia leaders like Carlos Marcello and Joey Aiuppa; Marcello was deported to Guatemala, while Aiuppa was convicted of violating of the Migratory Bird Treaty Act of 1918.[219] The attorney general's top target was perhaps Jimmy Hoffa, the head of the Teamsters Union. The Justice Department's "Get Hoffa Squad" ultimately secured the conviction of over 100 Teamsters, including Hoffa, who was convicted of jury tampering and pension fund fraud.[220]

Federal and military death penalty

As president, Kennedy oversaw the last federal execution prior to Furman v. Georgia, a 1972 case that led to a moratorium on federal executions.[221] Victor Feguer was sentenced to death by a federal court in Iowa and was executed on March 15, 1963.[222] Kennedy commuted a death sentence imposed by a military court on seaman Jimmie Henderson on February 12, 1962, changing the penalty to life in prison.[223] On March 22, 1962, Kennedy signed into law HR5143 (PL87-423), abolishing the mandatory death penalty for first degree murder in the District of Columbia, the only remaining jurisdiction in the United States with such a penalty.[224]

Native American relations

Construction of the Kinzua Dam flooded 10,000 acres (4,047 ha) of Seneca nation land that they had occupied under the Treaty of 1794, and forced 600 Seneca to relocate to Salamanca, New York. Kennedy was asked by the American Civil Liberties Union to intervene and to halt the project, but he declined, citing a critical need for flood control. He expressed concern about the plight of the Seneca, and directed government agencies to assist in obtaining more land, damages, and assistance to help mitigate their displacement.[225][226]

Agriculture

Kennedy had relatively little interest in agricultural issues, but he sought to remedy the issue of overproduction, boost the income of farmers, and lower federal expenditures on agriculture. Under the direction of Secretary of Agriculture Orville Freeman, the administration sought to limit the production of farmers, but these proposals were generally defeated in Congress. To increase demand for domestic agricultural products and help the impoverished, Kennedy launched a pilot Food Stamp program and expanded the federal school lunch program.[227]

Assassination

President Kennedy was assassinated in Dallas, Texas, at 12:30 pm Central Standard Time on November 22, 1963, while on a political trip to Texas to smooth over frictions in the Democratic Party between liberals Ralph Yarborough and Don Yarborough and conservative John Connally.[228] Traveling in a presidential motorcade through downtown Dallas with Jackie Kennedy, Connally, and Connally's wife, Nelly, Kennedy was shot in the head and neck. He was taken to Parkland Hospital for emergency medical treatment, but was pronounced dead at 1:00 pm.[229]

Hours after the assassination, Lee Harvey Oswald, an order filler at the Texas School Book Depository, was arrested for the murder of police officer J. D. Tippit, and was subsequently charged with Kennedy's assassination. Oswald denied the charges, but was killed by strip-club owner Jack Ruby on November 24. Ruby claimed to have killed Oswald due to his own grief over Kennedy's death, but the assassination of Kennedy and the death of Oswald gave rise to enormous speculation that Kennedy had been the victim of a conspiracy.[230] Kennedy was succeeded as president by Lyndon Johnson, who stated on November 27 that "no memorial or oration or eulogy could more eloquently honor President Kennedy's memory than the earliest possible passage of a civil rights bill for which he fought so long."[231]

President Johnson created the Warren Commission—chaired by Chief Justice Earl Warren—to investigate the assassination. The Warren Commission concluded that Oswald acted alone in killing Kennedy, and that Oswald was not part of any conspiracy.[232] The results of this investigation are disputed by many.[233] Various theories place the blame for the assassination on Cuba, the Soviet Union, the Mafia, the CIA, the FBI, top military leaders, or Johnson himself.[234] A 2004 Fox News poll found that 66% of Americans thought there had been a conspiracy to kill President Kennedy, while 74% thought that there had been a cover-up.[235] A Gallup Poll in mid-November 2013, showed 61% believed in a conspiracy, and only 30% thought that Oswald did it alone.[236] In 1979, the United States House Select Committee on Assassinations concluded that Oswald shot Kennedy, and that neither a foreign government nor a U.S. governmental institution had been involved in the shooting. However, the committee also found that there was a "high probability" that a second shooter, possibly with connections to the Mafia, had fired at Kennedy.[237]

The assassination had an enormous impact on the American public and contributed to a growing distrust of governmental institutions.[238] Giglio writes that Kennedy's assassination "invoked immeasurable grief," adding, "[t]o many Americans, John Kennedy's death ended an age of excellence, innocence, hope, and optimism."[239] In 2002, historian Carl M. Brauer concluded that the public's "fascination with the assassination may indicate a psychological denial of Kennedy's death, a mass wish...to undo it."[232]

Historical reputation

Assassinated in the prime of life, Kennedy remains a powerful and popular symbol of both inspiration and tragedy.[240] The term "Camelot" is often used to describe his presidency, reflecting both the mythic grandeur accorded Kennedy in death, and the powerful nostalgia that many feel for that era of American history.[241] He is idolized like Abraham Lincoln and Franklin D. Roosevelt; Gallup Poll surveys consistently show his public approval rating to be around 80 percent.[240] Kennedy's legacy strongly influenced a generation of neoliberal Democratic leaders, including Bill Clinton, Al Gore, Michael Dukakis, and Gary Hart.[242]

Historians and political scientists tend to rank Kennedy as an above-average president, and he is usually the highest-ranking president who served less than one full term.[243] Assessments of his policies are mixed. The early part of his administration carried missteps highlighted by the failed Bay of Pigs invasion and the 1961 Vienna summit.[244][241] The second half of his presidency was filled with several notable successes, for which he receives acclaim. He skillfully handled the Cuban Missile Crisis, as he avoided nuclear war and set the stage for a less tense era of U.S.–Soviet relations.[244][241] On the other hand, his escalation of the U.S. presence in Vietnam has been criticized.[244] Kennedy's effectiveness in domestic affairs has also been the subject of debate. Giglio notes that many of Kennedy's proposals were adopted by Congress, but his most important programs, including health insurance for the elderly, federal aid to education, and tax reform, were blocked during his presidency. [245] Many of Kennedy's proposals were passed after his death, during the Johnson administration, and Kennedy's death gave those proposals a powerful moral component.[240]

A 2014 Washington Post survey of 162 members of the American Political Science Association's Presidents and Executive Politics section ranked Kennedy 14th highest overall among the 43 persons who have been president, including then-president Barack Obama. Then among the "modern presidents", the thirteen from Franklin Roosevelt through Obama, he places in the middle of the pack. The survey also found Kennedy to be the most overrated U.S. president.[246] A 2017 C-SPAN survey has Kennedy ranked among the top ten presidents of all-time. The survey asked 91 presidential historians to rank the 43 former presidents (including then-president Barack Obama) in various categories to come up with a composite score, resulting in an overall ranking. Kennedy was ranked 8th among all former presidents (down from 6th in 2009). His rankings in the various categories of this most recent poll were as follows: public persuasion (6), crisis leadership (7), economic management (7), moral authority (15), international relations (14), administrative skills (15), relations with congress (12), vision/setting an agenda (9), pursued equal justice for all (7), performance with context of times (9).[247] A 2018 poll of the American Political Science Association’s Presidents and Executive Politics section ranked Kennedy as the 16th best president.[248] A 2006 poll of historians ranked Kennedy's decision to authorize the Bay of Pigs invasion as the eighth-worst mistake made by a sitting president.[249]

Notes

- Southern Democrats in several states who were opposed to the national Democratic Party's support for civil rights and voting rights for African Americans living in the South, attempted to block Kennedy's election by denying him the necessary number of electoral votes (269 of 537) for victory.[8][7]

- Henry D. Irwin, who had been pledged to vote for Nixon.[9]

- Theodore Roosevelt was nine months younger when he first assumed the presidency on September 14, 1901, but he was not elected to the office until 1904, when he was 46.[13]

- The groups were: American Jewish Congress, American Veterans Committee, Americans for Democratic Action, Anti-Defamation League of B'Nai B'rith, International Union of Electrical Workers (AFL-CIO), National Assn. for the Advancement of Colored People, and United Automobile Workers (AFL-CIO).

References

- Giglio 2006, pp. 12–13.

- Giglio 2006, pp. 16–17.

- "John F. Kennedy: Campaigns and Elections". Miller Center of Public Affairs, University of Virginia. Retrieved February 19, 2017.

- Caro, Robert A. (2012). The Passage of Power. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. pp. 121–135. ISBN 978-0-679-40507-8.

- Giglio 2006, p. 17.

- Reeves 1993, p. 15.

- Dudley & Shiraev 2008, p. 83.

- "See No Electoral College Block". Chicago Tribune. Chicago, Illinois. November 28, 1960. Retrieved April 26, 2017.

- Edwards, George C. (2011) [2004]. Why the Electoral College Is Bad for America (2nd ed.). Yale University Press. pp. 22–23. ISBN 978-0-300-16649-1.

- Patterson 1996, p. 441.

- Carroll, Wallace (January 21, 1961). "A Time of Change Facing Kennedy; Themes of Inaugural Note Future of Nation Under Challenge of New Era". The New York Times. p. 9.

- Reeves 1993, p. 21.

- Hoberek, Andrew, ed. (2015). The Cambridge Companion to John F. Kennedy. Cambridge Companions to American Studies. New York: Cambridge University Press. p. 1. ISBN 978-1-107-66316-9.

- "FAQ". The Pulitzer Prizes. Columbia University. Archived from the original on August 1, 2016. Retrieved February 23, 2012.

- "The 44th Presidential Inauguration: January 20, 1961". Joint Congressional Committee on Inaugural Ceremonies. Retrieved April 4, 2017.

- Kennedy, John F. (January 20, 1961). "Inaugural Address". John F. Kennedy Presidential Library. Archived from the original on January 11, 2012. Retrieved February 22, 2012.

- Kempe 2011, p. 52.

- Robert Dallek, Camelot's Court: Inside the Kennedy (2013)

- Giglio 2006, pp. 20–21.

- "Bobby Kennedy: Is He the 'Assistant President'?". US News and World Report. February 19, 1962. Retrieved August 31, 2016.

- Giglio 2006, p. 37.

- Reeves 1993, p. 22.

- Reeves 1993, pp. 23, 25.

- Giglio 2006, pp. 31–32, 35.

- Andrew Preston, "The Little State Department: McGeorge Bundy and the National Security Council Staff, 1961‐65." Presidential Studies Quarterly 31.4 (2001): 635-659. Online

- Giglio 2006, pp. 35–37.

- Brinkley 2012, p. 55.

- Patterson 1996, p. 459.

- Giglio 2006, pp. 32–33, 64, 69.

- Giglio 2006, pp. 41–43.

- Abraham, Henry Julian (2008). Justices, Presidents, and Senators: A History of the U.S. Supreme Court Appointments from Washington to Bush II. Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 217–221. ISBN 9780742558953.

- Giglio 2006, pp. 44–45.

- Herring 2008, pp. 704–705.

- Brinkley 2012, pp. 76–77.

- Patterson 1996, pp. 489–490.

- Stephen G Rabe, “John F. Kennedy” in Timothy J Lynch, ed., ‘’The Oxford Encyclopedia of American Military and Diplomatic History’’ ( 2013) 1:610-615.

- Giglio 2006, pp. 50–51.

- Schlesinger 2002, pp. 233, 238.

- Gleijeses, Piero (February 1995). "Ships in the Night: The CIA, the White House and the Bay of Pigs". Journal of Latin American Studies. 27 (1): 1–42. doi:10.1017/S0022216X00010154. ISSN 0022-216X – via JSTOR.

- Reeves 1993, pp. 69–73.

- "50 Years Later: Learning From The Bay Of Pigs". NPR. April 17, 2011. Retrieved September 1, 2016.

- Giglio 2006, pp. 52–55.

- Reeves 1993, pp. 71, 673.

- Brinkley 2012, pp. 68–69.

- Patterson 1996, pp. 493–495.

- Schlesinger 2002, pp. 268–294, 838–839.

- Reeves 1993, pp. 95–97.

- Schlesinger 2002, pp. 290, 295.

- Dallek 2003, pp. 370–371.

- Brinkley 2012, pp. 70–71.