Ned Lamont

Edward Miner Lamont Jr. (born January 3, 1954) is an American businessman and politician serving as the 89th governor of Connecticut since January 9, 2019.[1][2] A member of the Democratic Party, he served as a Greenwich selectman from 1987 to 1989. He ran for the U.S. Senate in 2006, defeating incumbent Senator Joe Lieberman in the state Democratic primary election, but was defeated in the general election by Lieberman, who then ran as a third-party candidate.[3]

Ned Lamont | |

|---|---|

| |

| 89th Governor of Connecticut | |

| Assumed office January 9, 2019 | |

| Lieutenant | Susan Bysiewicz |

| Preceded by | Dan Malloy |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Edward Miner Lamont Jr. January 3, 1954 Washington, D.C., U.S. |

| Political party | Democratic |

| Spouse(s) | |

| Children | 3 |

| Residence | Governor's Mansion |

| Education | Harvard University (BA) Yale University (MBA) |

| Website | Government website |

Lamont then ran for governor in 2010, but was defeated in the Democratic primary by former Stamford mayor Dan Malloy, who went on to win the general election. Lamont ran again in 2018, winning the party nomination and defeating Republican Bob Stefanowski in the general election.[3] He uses his nickname Ned in his official capacity as governor, as he has done throughout his public life.[4]

Early life and education

Lamont was born on January 3, 1954, in Washington, D.C., to Camille Helene (née Buzby) and Edward Miner Lamont. His mother was born in San Juan, Puerto Rico to parents from the U.S. mainland, and later worked as a staffer for Senator Estes Kefauver.[5] His father, an economist, worked on the Marshall Plan and then served in the Department of Housing and Urban Development during the Nixon administration.[6] He is the great-grandson of former J. P. Morgan & Co. chair Thomas W. Lamont[7][8] and a grand-nephew of former American Civil Liberties Union director Corliss Lamont.[9] He is a distant descendant of colonial diarist Thomas Minor, from whom he gets his middle name.[10][lower-alpha 1]

Lamont's family moved to Laurel Hollow on Long Island when he was seven years old.[lower-alpha 2] The eldest of three children, he and his sisters attended East Woods School.[5][12] He later attended Phillips Exeter Academy, and served as president of the student newspaper, The Exonian. After graduating from Phillips Exeter in 1972, he earned a Bachelor of Arts in sociology from Harvard College in 1976 and a Master of Business Administration from the Yale School of Management in 1980.[12][13]

Professional career

In 1977, Lamont became editor for the Black River Tribune, a small weekly newspaper in Ludlow, Vermont. During his time there, he worked alongside journalists Jane Mayer and Alex Beam.[14] After graduating from Yale, he entered the cable television industry, managing the startup operation in Fairfield County, Connecticut for Cablevision.[13] In 1984, he founded Campus Televideo, a company that provides cable and satellite services to college campuses across the United States.[15][16] He later chaired Lamont Digital Systems, a telecommunications firm that invests in new media startups.[17][18] Campus Televideo was its largest division before Austin, Texas-based firm Apogee acquired it on September 3, 2015.[19][16]

Lamont has served on the board of trustees for the Conservation Services Group,[20] Mercy Corps,[21] the Norman Rockwell Museum,[22] the YMCA, and the Young Presidents' Organization.[23] He has also served on the advisory boards of the Yale School of Management[24] and the Brookings Institution.[23]

Early political career

Lamont was first elected in 1987 as a selectman in Greenwich, Connecticut, where he served for one term. He ran for state senate in 1990, where he faced Republican William Nickerson and incumbent senator Emil "Bennie" Benvenuto (who had switched his party affiliation from Republican to A Connecticut Party).[25] Nickerson won the three-way race with Lamont finishing in third place.[26] Lamont later served for three terms on the Greenwich town finance board and chaired the State Investment Advisory Council, which oversees state pension fund investments. During his term as chair, the state saw its unfunded liabilities reduced and pension fund performance improved.[27]

2006 U.S. Senate election

.jpg)

On March 13, 2006, Lamont announced his campaign for the U.S. Senate against incumbent Joe Lieberman.[28]

On July 6, Lamont faced off against Lieberman in a televised debate that covered issues such as the Iraq War, energy policy, and immigration. During the debate, Lieberman argued he was being subjected to a litmus test on the war, insisted he was a "bread-and-butter Democrat," and on many occasions asked, "who is Ned Lamont?" Lieberman then asked Lamont if he would release his income tax returns, which he did afterwards.[29]

Lamont focused on Lieberman's supportive relationship with Republicans, telling him "if you won't challenge President Bush and his failed agenda, I will." He criticized Lieberman's vote for the Energy Policy Act of 2005, which he dubbed the "Bush-Cheney-Lieberman energy bill." In response to the assertion that he supported Republican policies, Lieberman stated he had voted with Senate Democrats 90% of the time. Lamont argued the three-term incumbent lacked the courage to challenge the Bush administration on the Iraq War.[29] He also criticized Lieberman for supporting federal intervention in the Terri Schiavo case.[30][31]

On July 30, The New York Times editorial board endorsed Lamont.[32] That same day, The Sunday Times reported former President Bill Clinton warned Lieberman not to run as an independent if he lost the primary to Lamont.[33] Pledging to refuse money from lobbyists during the election, Lamont funded most of his own campaign, with donations exceeding $12.7 million.[34][35]

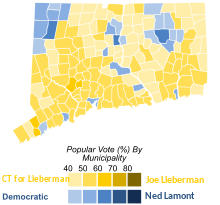

Lamont won the primary with 52% of the vote[36] (this was the only Senate race in 2006 where an incumbent lost re-nomination). In his concession speech, Lieberman announced he was standing by his earlier statements that he would run as an independent if he lost the Democratic primary.[37] Running under the banner of Connecticut for Lieberman, Lieberman won the general election with nearly 50% of the vote (exit polls showed Lieberman won 33% of Democrats, 54% of independents, and 70% of Republicans).[38] The Sundance Channel documentary film Blog Wars chronicled the influence political blogging had on the election.[39]

While some Research 2000 polls commissioned by the Daily Kos in 2007 and 2008 found he would win a Senate rematch with Lieberman by growing margins,[40][41] Lamont stated he was not considering another campaign for Senate.[42]

2008 presidential campaign activity

Lamont initially supported Chris Dodd's presidential campaign.[43][44] After Dodd dropped out of the race, Lamont became a state co-chair for Barack Obama's presidential campaign.[45] Obama's victory in the Connecticut Democratic primary was credited to Lamont's ability to turn out the voter base he had built during his Senate campaign.[46] In March 2008, he was elected as a state delegate to the 2008 Democratic National Convention, his support pledged to Obama.[47]

Academic career

_(cropped).jpg)

Before the 2006 election, Lamont had volunteered at Warren Harding High School in Bridgeport, where he focused on teaching entrepreneurship and coordinating internships with local businesses.[48][49] After the election, he served as a teaching fellow at the Harvard Institute of Politics[50] and the Yale School of Management. He then became an adjunct faculty member and chair of the Arts and Sciences Public Policy Committee at Central Connecticut State University (CCSU), where he was named Distinguished Professor of Political Science and Philosophy.[49] During his time at CCSU, he was a lecturer in multiple classes and founded a business startup competition.[49][51] In 2019, he delivered the commencement speech for CCSU, his first as governor.[52]

Governor of Connecticut (2019–present)

Elections

2010

On February 16, 2010, Lamont announced his candidacy for the 2010 gubernatorial election.[53] Former Stamford mayor Dan Malloy defeated him at the state Democratic convention on May 22, receiving 1,232 votes (68%) to Lamont's 582 votes (32%). Since he won more than 15% of the vote, Lamont was eligible to appear on the primary election ballot.[54] On August 10, he lost the primary election to Malloy, receiving only 43% of the vote.[55] Malloy would go on to defeat Republican candidate Thomas C. Foley in the general election.[56]

2018

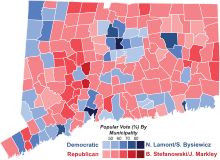

On January 17, 2018, Lamont announced his candidacy to succeed Malloy, who was not seeking a third term.[57][3] He received the party endorsement at the state convention, and chose former Connecticut Secretary of State Susan Bysiewicz as his running mate. While missing the 15% threshold, Bridgeport mayor and former convict Joe Ganim had gathered enough signatures to appear on the Democratic primary ballot.[58] Despite the challenge, Lamont won the primary by over 130,000 votes (a 62.4% margin).[3][59] He then faced Republican Bob Stefanowski and independent Oz Griebel in the general election on November 6. Later that night, Greibel conceded the election, while Stefanowski conceded to Lamont early the next morning.[2]

Tenure

Lamont was sworn in as the 89th governor of Connecticut on January 9, 2019, succeeding Dan Malloy.[60] Some of his top priorities include: implementing electronic tolls on state highways, taxing online streaming services, restoring the property tax credit, legalizing marijuana for recreational usage, increasing the minimum wage to $15 per hour, instituting paid family and medical leave, renegotiating contracts with public-sector unions, and legalizing sports betting.[61] His proposal to implement electronic tolling on state highways has been viewed unfavorably by residents and has faced opposition from fellow Democrats in the General Assembly.[62][63]

He has also prioritized investments in rail infrastructure, proposing shorter travel times between cities by upgrading rail lines, as well as extending the Danbury Branch to New Milford and re-electrifying the line.[64][65]

In February 2019, Lamont appointed former PepsiCo CEO Indra Nooyi co-director of the Connecticut Economic Resource Center (CERC), a public-private partnership with the Department of Economic and Community Development tasked with revamping the state's economic development strategy.[66][67] A year later, CERC rebranded itself as AdvanceCT.[68]

In April 2019, Lamont signed his first executive order which directs state office buildings and vehicle fleets to become more energy-efficient through an expanded “Lead By Example Sustainability Initiative." The initiative aims to reduce both the carbon footprint and cost of state government operations.[69] On May 29, he signed a bill that raised the state minimum wage to $11 an hour that October and will eventually raise it to $15 an hour by 2023.[70] On June 3, he signed three gun control bills including Ethan's Law, which requires safely storing firearms in households where children are present, bans ghost guns, and bans storing unlocked guns in unattended vehicles.[71] That same month, he signed a bill that banned gay panic defense in Connecticut.[72][73][74]

In the aftermath of the 2019 Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress crash, which resulted in seven deaths and six injuries, Lamont was joined with Senator Richard Blumenthal in offering condolences to the families affected and ensuring them that the NTSB would launch a thorough investigation.[75] Lamont later met with the first responders to thank them for their service.[76]

Approval ratings

Since being elected governor, Connecticut residents have viewed Lamont unfavorably. Morning Consult has listed him among the top ten least popular governors every quarter since his election. In a survey conducted in the last quarter of 2019, he was ranked the fourth most unpopular governor in the United States, with a 51% disapproval rating and a 32% approval rating.[77]

However, in the aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic, he has received higher approval ratings. In a May 2020 Quinnipiac Poll, Lamont received a 65% approval rating and a 26% disapproval rating, with a 78% approval rating for his handling of the pandemic specifically.[78]

Personal life

On September 10, 1983,[79] Lamont married Ann Huntress, a venture capitalist and managing partner at Oak Investment Partners.[23][80] They have three children: Emily, Lindsay, and Teddy.[23] He and his family live in Greenwich and have a vacation home in North Haven, Maine.[12]

The Lamont Gallery on the campus of Phillips Exeter Academy and the Lamont Library at Harvard University are both named in honor of his family.[12]

Notes

References

- "Happy Birthday to Greenwich's Ned Lamont Jr". Greenwich Daily Voice. January 3, 2014. Retrieved August 15, 2018.

- Vigdor, Neil; Kovner, Josh; Lender, Jon; Ormseth, Matthew; Megan, Kathleen; Rondinone, Nicholas (November 7, 2018). "Bob Stefanowski Concedes Governor's Race After Cities Push Ned Lamont To Victory". Hartford Courant. Retrieved November 7, 2018.

- Blair, Russell (January 17, 2018). "Ned Lamont Jumps Into Connecticut Governor's Race". Hartford Courant. Retrieved January 17, 2018.

- Altimari, Daniela (December 12, 2018). "Ned or Edward? Lamont keeps it informal as governor". Hartford Courant. Retrieved June 10, 2019.

- "Camille Lamont Obituary". The New York Times. January 14, 2015. Retrieved October 9, 2016.

- Nichols, John (July 27, 2006). "A Fight for the Party's Soul". The Nation. Retrieved February 8, 2013.

- Reitwiesner, William Addams. "Ancestry of Ned Lamont". Retrieved February 8, 2013.

- Krayeske, Ken (January 24, 2006). "Ned Lamont (interview)". The 40-Year Plan. Archived from the original on February 25, 2007. Retrieved August 5, 2013.

- "The Life of Corliss Lamont". Half-Moon Foundation, Inc. May 27, 2018. Retrieved August 15, 2018.

- Sleeper, Jim (October 15, 2006). "The American Lamonts". The New York Times. Retrieved February 27, 2019.

- Miner, John A. and Miner, Robert F. "The Curious Pedigree of Lt. Thomas Minor". New England Historical and Genealogical Register. New England Historic Genealogical Society. July 1984, pg 182-185. Accessed 14 July 2007.

- Kershaw, Sarah; Cowan, Alison Leigh (November 1, 2006). "A Son of Privilege Takes His Baby Steps on the Political Proving Ground". The New York Times. Retrieved November 9, 2018.

- "Ned Lamont: Democrat candidate for Governor". The Connecticut Mirror. Archived from the original on July 4, 2010. Retrieved August 5, 2013.

- Keating, Christopher (August 2, 2010). "Unknown No Longer, Lamont Runs For Governor". Hartford Courant. Retrieved August 28, 2018.

- Bingham, Michael C. (July 20, 2018). "Lamont in the lion's den". New Haven Biz. Retrieved August 29, 2018.

- Keating, Christopher (January 19, 2018). "After Selling Cable Company, Ned Lamont is 'All In'". Hartford Courant. Retrieved August 29, 2018.

- "Lamont Digital Systems Inc". Bloomberg. Retrieved August 28, 2018.

- Haar, Dan (July 28, 2018). "Ned Lamont's cable business launched with tip from MTV". Connecticut Post. Retrieved August 28, 2018.

- "Apogee Acquires Campus Televideo -- Becomes Higher Education's Largest ResNet and Video Solutions Provider". Market Wired. September 3, 2015.

- "About Ned". Ned for CT. Archived from the original on October 21, 2018. Retrieved November 29, 2018.

- Portella, Joy (June 30, 2009). "Ned Lamont calls out Mercy Corps' work on The Huffington Post". Mercy Corps. Retrieved August 29, 2018.

- "Norman Rockwell Museum Announces New Board Members". Norman Rockwell Museum. September 9, 2011. Retrieved February 8, 2013.

- "Ned Lamont Makes a Run for the US Senate". ilovefc.com. Moffly Media. April 19, 2006. Retrieved August 15, 2018.

- "Yale SOM Board of Advisors". Yale School of Management. Yale University. Retrieved August 15, 2018.

- Keating, Christopher (October 12, 2011). "Greenwich Mourns Death Of Former Sen. Bennie Benvenuto; Ran Against Ned Lamont And Bill Nickerson In Three-Way 1990 State Senate Race". Hartford Courant. Retrieved January 2, 2019.

- "CT State Senate 36". Our Campaigns. Retrieved March 4, 2020.

- "Lamont Grants MyLeftNutmeg First Blogger Interview". MyLeftNutmeg. January 13, 2006. Archived from the original on June 13, 2006. Retrieved August 3, 2006.

- Cordero, Melina (April 6, 2006). "Lamont courts local voters". Yale Daily News. Retrieved February 8, 2013.

- "Lieberman, Lamont Face Off In NBC 30 Debate". WVIT. July 6, 2006. Archived from the original on December 25, 2007. Retrieved August 5, 2013.

- Seder, Sam (March 21, 2006). "Why Ned Lamont is a Democrat". In These Times. Retrieved August 15, 2018.

- Golson, Blair (April 26, 2006). "Ned Lamont: The Truthdig Interview". TruthDig. Retrieved August 15, 2018.

- "A Senate Race in Connecticut". The New York Times. July 30, 2006. Retrieved August 15, 2018.

- Allen-Mills, Tony (July 30, 2006). "The anti-war tycoon splits Democrats". The Sunday Times. Retrieved August 3, 2006.

- Miga, Andrew (October 21, 2006). "Lamont Gives $2M to Flagging Campaign". The Washington Post. Retrieved February 8, 2013.

- Lamont, Ned (April 3, 2006). "4,000 Donors in First Quarter". LamontBlog. Retrieved August 5, 2013.

- "Connecticut primary results". Hartford Courant. August 10, 2006. Archived from the original on March 25, 2013. Retrieved August 5, 2013.

- "Lieberman concedes; Lamont wins primary". NBC News. August 9, 2006. Retrieved February 8, 2013.

- "America Votes 2006: Exit Polls". CNN. Retrieved August 5, 2013.

- Hinderaker, John (December 26, 2006). "Blog Wars". Power Line. Retrieved March 4, 2019.

- Moulitsas, Markos (April 7, 2008). "CT-Sen: Lieberman's popularity continues to slide". Daily Kos. Retrieved August 5, 2013.

- Alarkon, Walter (July 6, 2008). "Poll: Lieberman Would Lose to Lamont". The Hill. Retrieved February 8, 2013.

- Pazniokas, Mark (December 8, 2010). "Lamont not looking for a rematch with Lieberman in 2012". Connecticut Mirror. Retrieved August 5, 2013.

- Melber, Ari (February 25, 2007). "Ned Lamont Backs Habeas Corpus- and Chris Dodd". The Huffington Post. Retrieved February 8, 2013.

- Gombeski, Christopher (November 10, 2007). ""Ned Who" No More: An interview with Ned Lamont". The Politic. Archived from the original on December 25, 2007. Retrieved August 15, 2008.

- Lamont, Ned (March 28, 2008). "Why I'm Supporting Barack Obama". The Huffington Post. Retrieved February 8, 2013.

- Chen, David W. (February 6, 2008). "Obama Takes Connecticut, Helped by Lamont Voters". The New York Times. Retrieved May 20, 2010.

- "Connecticut Democratic Delegation 2008". The Green Papers. February 5, 2008. Retrieved July 17, 2013.

- Lockhart, Brian (June 13, 2018). "Fact checking Lamont's ties to Harding High". Connecticut Post. Retrieved October 29, 2018.

- "Edward Miner "Ned" Lamont, Jr., Connecticut Governor". Coalition of Northeastern Governors. Retrieved November 22, 2019.

- "Former Fellows-The Institute of Politics". Harvard Institute of Politics. Harvard University. Archived from the original on October 22, 2012. Retrieved February 8, 2013.

- Krasselt, Kaitlyn (October 21, 2018). "Ned Lamont's eight-year break from politics". CT Post. Retrieved November 22, 2019.

- "Gov. Ned Lamont to deliver commencement remarks at CCSU". Associated Press. May 12, 2019. Retrieved June 7, 2019.

- Pazniokas, Mark (February 16, 2010). "Lamont announces for governor, pitching himself as an outsider". Connecticut Mirror. Retrieved August 29, 2010.

- "Democrats: Malloy and Wyman vs. Lamont and Glassman". Connecticut Mirror. May 22, 2010. Retrieved June 11, 2010.

- Hernandez, Raymond (August 10, 2010). "Lamont Loses Connecticut Primary for Governor". The New York Times. Retrieved February 8, 2013.

- Montopoli, Brian (November 8, 2010). "Tom Foley Concedes CT Governor Race". CBS News.

- Colli, George (November 28, 2017). "Source: Ned Lamont "thinking seriously" about run for governor". WTNH. Retrieved November 28, 2017.

- Vigdor, Neil (June 19, 2018). "Joe Ganim And David Stemerman Qualify For Primaries For Governor". Hartford Courant. Retrieved November 13, 2018.

- Vigdor, Neil; Altimari, Daniela; Keating, Chris; Gomez-Aceves, Sandra (May 19, 2018). "Second Chances: Democrats Endorse Ned Lamont For Governor, Joe Ganim Plans To Primary". Hartford Courant. Retrieved May 19, 2018.

- Pazniokas, Mark; Phaneuf, Keith M. (November 7, 2018). "Stefanowski concedes race to Lamont: 'He won fair and square'". The Day. Retrieved November 8, 2018.

- Keating, Christopher (November 18, 2018). "Gov.-elect Ned Lamont made a lot of campaign promises. Which ones might happen?". Hartford Courant. Retrieved November 21, 2018.

- Stuart, Christine (March 12, 2019). "Poll Finds That Tolls Are Still Unpopular". CT News Junkie. Retrieved January 25, 2020.

- Pazniokas, Mark; Phaneuf, Keith M. (November 13, 2019). "Lamont rebuffed on tolls by Senate Democrats". CT Mirror. Retrieved January 25, 2020.

- Blair, Russell (January 9, 2019). "7 key lines from Ned Lamont's State of the State speech". Hartford Courant. Retrieved January 10, 2019.

- Perrefort, Dirk (June 30, 2010). "Gubernatorial candidate Ned Lamont talks transit at Danbury train station". Danbury News-Times. Retrieved January 10, 2019.

- Pazniokas, Mark (February 1, 2019). "A Wall Street exec volunteers, and Lamont readily accepts". CT Mirror. Retrieved March 4, 2020.

- Staff reporter (February 11, 2019). "Connecticut Governor Names Indian American Executive Indra Nooyi to CERC Board of Directors to Improve Economic Strategy". India West. Retrieved March 4, 2020.

- "About Us". Retrieved March 5, 2020.

- WTNH staff (April 24, 2019). "Lamont wants Connecticut to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 45 percent by 2030". News 8. Retrieved June 6, 2019.

- Gstalter, Morgan (May 29, 2019). "Connecticut governor signs bill to gradually raise minimum wage to $15". The Hill. Retrieved June 6, 2019.

- Larson, Shannon (June 3, 2019). "Gov. Lamont signs three gun control bills, including Ethan's Law". Hartford Courant. Retrieved June 6, 2019.

- "Connecticut lawmakers move to ban 'gay panic defense'". Yahoo News. June 4, 2019. Retrieved March 4, 2020.

- Altimari, Daniela (June 4, 2019). "Bill banning gay panic defense gets final passage in the House". Hartford Courant. Retrieved March 4, 2020.

- "CT SB00058". LegiScan. Retrieved March 4, 2020.

- Pascus, Brian (October 2, 2019). "World War II-era bomber plane crashes at Bradley Airport in Connecticut; fatalities confirmed". CBS News. Retrieved November 15, 2019.

- Burchill, Caitlin (October 30, 2019). "Governor Thanks B17 Survivor and Responding Air National Guard Members". NBC Connecticut. Retrieved November 15, 2019.

- "Morning Consult's Governor Approval Ratings". Morning Consult. April 2019. Retrieved May 17, 2019.

- "Q poll: Lamont popularity high, CT respondents oppose quick reopening of the state". Quinnipiac University Polling Institute. May 6, 2020. Retrieved June 17, 2020.

- "Ann Huntress to Wed E.M. Lamont Jr". The New York Times. July 17, 1983. Retrieved October 22, 2018.

- Cowan, Alison Leigh (October 16, 2006). "Not-So-Hidden Asset, His Wife, Is Force in Lamont's Senate Bid". The New York Times. Retrieved February 8, 2013.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Ned Lamont. |

| Wikinews has news related to: |

- Governor Ned Lamont official government website

- Ned Lamont at Curlie

- Appearances on C-SPAN

- Ned Lamont at On the Issues

| Party political offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Joe Lieberman |

Democratic nominee for U.S. Senator from Connecticut (Class 1) 2006 |

Succeeded by Chris Murphy |

| Preceded by Dan Malloy |

Democratic nominee for Governor of Connecticut 2018 |

Most recent |

| Political offices | ||

| Preceded by Dan Malloy |

Governor of Connecticut 2019–present |

Incumbent |

| U.S. order of precedence (ceremonial) | ||

| Preceded by Mike Pence as Vice President |

Order of Precedence of the United States Within Connecticut |

Succeeded by Mayor of city in which event is held |

| Succeeded by Otherwise Nancy Pelosi as Speaker of the U.S. House of Representatives | ||

| Preceded by Brian Kemp as Governor of Georgia |

Order of Precedence of the United States Outside Connecticut |

Succeeded by Charlie Baker as Governor of Massachusetts |