Namaste

Namaste (/ˈnɑːməsteɪ/, Devanagari: नमस्ते, Hindi pronunciation: [nəməsteː] (![]()

Western uses of namaste, as a slogan or spoken during physical fitness classes, are perceived by some as an insensitive misappropriation of the greeting.[5]

Etymology, meaning and origins

Right: Entrance pillar relief (Thrichittatt Maha Vishnu Temple, Kerala, India).

Namaste (Namas + te) is derived from Sanskrit and is a combination of the word namas and the second person dative pronoun in its enclitic form, te.[6] The word namaḥ takes the sandhi form namas before the sound te.[7][8]

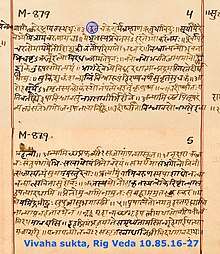

The term namas is made of 2 words na meaning “not” and mamah meaning “i” or mine. It is therefore “not I”. This implies being open to the person being greeted and sometimes when “namaste” is said to God it refers to bowing or adoration. The subtle difference between bowing and openness is important. When greeting a peer or a stranger, “not I” accords respect to the other while maintaining self respect for oneself. When addressing God, “not I” can be interpreted as bowing. However, it is important to understand the distinction: “not I” is not bowing but according respect to the person being greeted. It is found in the Vedic literature. Namas-krita and related terms appear in the Hindu scripture Rigveda such as in the Vivaha Sukta, verse 10.85.22[9] in the sense of "worship, adore", while Namaskara appears in the sense of "exclamatory adoration, homage, salutation and worship" in the Atharvaveda, the Taittiriya Samhita, and the Aitareya Brahmana. It is an expression of veneration, worship, reverence, an "offering of homage" and "adoration" in the Vedic literature and post-Vedic texts such as the Mahabharata.[10][11] The phrase Namas-te appears with this meaning in Rigveda 8.75.10,[12] Atharvaveda verse 6.13.2, Taittirya Samhita 2.6.11.2 and in numerous other instances in many early Hindu texts.[13] It is also found in numerous ancient and medieval era sculpture and mandapa relief artwork in Hindu temples.[14]

In the contemporary era, namaḥ means 'bow', 'obeisance', 'reverential salutation' or 'adoration'[15] and te means 'to you' (singular dative case of 'tvam'). Therefore, namaste literally means "bowing to you".[16] In Hinduism, it also has a spiritual import reflecting the belief that "the divine and self (atman, soul) is same in you and me", and connotes "I bow to the divine in you".[17][1][18] According to sociologist Holly Oxhandler, it is a Hindu term which means "the sacred in me recognizes the sacred in you".[19] In modern usage, though, namaste simply means "hello".[5]

A less common variant is used in the case of three or more people being addressed namely Namo vaḥ which is a combination of namaḥ and the enclitic second person plural pronoun vaḥ.[6] The word namaḥ takes the sandhi form namo before the sound v.[7] An even less common variant is used in the case of two people being addressed, namely, Namo vām, which is a combination of namaḥ and the enclitic second person dual pronoun vām.[6]

In contemporary practice, namaste is rarely spoken, as it is extremely formal and other greetings are generally more suitable depending on context. Some people feel that Namaste has been misappropriated as a general greeting or slogan in the West, particularly in yoga-as-fitness classes [5] Of course, the adoption of foreign words into another language is nothing new and the respect with which they are used has a large impact on whether or not the accusation of misappropriation can really be applied to everyone who uses those words. Just like there are some people from India who feel it is a strange or superficial adoption for Western yoga classes, there are also those who not only accept but even enjoy the evolution and use of the Hindu word in the Western world. [20]

Representations

Excavations for Indus Valley Civilization have revealed many male and female terracotta figures in namaste posture.[21][22] These archaeological findings are dated to be between 3000 BCE to 2000 BCE.[23][24]

Añjali Mudrā

.jpg)

Añjali Mudrā (Sanskrit: अञ्जलि मुद्रा), the salutation seal,[25][26] is a hand gesture associated with Indian religions, practiced throughout Southeast Asia. It is used as a sign of respect and a greeting in India, Sri Lanka, Nepal, Bhutan, Burma, Thailand, Laos, Cambodia and Indonesia, also used among East Asian Buddhists, Taoists and Shintoists and amongst yoga practitioners and adherents of similar traditions. The gesture is incorporated into many yoga asanas, and is used for worship in many Eastern religions.

The modern yoga pose praṇāmāsana (Sanskrit: प्रणामासन) consists of standing with the hands in añjali mudrā.

Etymology

Anjali is Sanskrit for "divine offering", "a gesture of reverence", "benediction", "salutation", and is derived from anj, meaning "to honour or celebrate".[26]

Mudra means "seal" or "sign". The meaning of the phrase is thus "salutation seal".[25]

The gesture is also known as hrdayanjali mudra meaning "reverence to the heart seal" (from hrd, meaning "heart") and atmanjali mudra meaning "reverence to the self seal" (from atman, meaning "self").[26]

Description

Anjali mudra is performed by pressing the palms of the hands together. The fingers are together with fingertips pointing up. The hands are pressed together firmly and evenly.[26]

In the most common form of anjali mudra, the hands are held at the heart chakra with thumbs resting lightly against the sternum.[26] The gesture may also be performed at the ajna or brow chakra with thumb tips resting against the "third eye" or at the crown chakra (above the head). In some yoga postures, the hands are placed in anjali mudra position to one side of the body or behind the back.

Anjali mudra is normally accompanied by a slight bowing of the head.

Symbolic meaning

Anjali mudra has the same meaning as the Sanskrit greeting Namaste and can be performed while saying Namaste or Pranam, or in place of vocalizing the word.

The gesture is used for both greetings and farewells, but carries a deeper significance than a simple "hello" or "goodbye". The joining together of the palms is said to provide connection between the right and left hemispheres of the brain and represents unification.[26][25] This yoking is symbolic of the practitioner's connection with the divine in all things. Hence, anjali mudra honours both the self and the other.[25]

Physical benefits

Anjali mudra is performed as part of a physical yoga practice with an aim to achieving several benefits. It is a "centering pose" which, according to practitioners, helps to alleviate mental stress and anxiety and is therefore used to assist the practitioner in achieving focus and coming into a meditative state.[26]

The physical execution of the pose helps to promote flexibility in the hands, wrists, fingers and arms.[26]

Use in full-body asanas

While anjali mudra may be performed by itself from any seated or standing posture, the gesture is also incorporated into physical yoga practice as part of many full-body asanas, including:

- Anjaneyasana (lunge) – with arms overhead[27]

- Hanumanasana (monkey pose)[28]

- Malasana (garland pose)[29]

- Matsyasana (fish pose) – an advanced variant[30]

- Prasarita Padottanasana (wide-legged forward bend) – an advanced variant with hands behind the back[31]

- Rajakapotasana (Pigeon Pose/King Pigeon Pose) – anjali mudra in Pigeon pose[32]

- Tadasana/samasthiti (mountain pose) – a variant of the pose used during sun salutation sequences[33]

- Utkatasana (chair pose, literally "fierce pose"), arms overhead

- Urdhva Hastasana (upward salute/extended mountain pose) – arms overhead[34]

- Virabhadrasana I (warrior I) – arms overhead[35]

- Vrikshasana (tree pose)[36]

Use

The gesture is widely used throughout the Indian subcontinent, parts of Asia and beyond where people of South and Southeast Asian origins have migrated.[17] Namaste or namaskar is used as a respectful form of greeting, acknowledging and welcoming a relative, guest or stranger.[3] In some contexts, Namaste is used by one person to express gratitude for assistance offered or given, and to thank the other person for his or her generous kindness.[37]

Namaskar is also part of the 16 upacharas used inside temples or any place of formal Puja (worship). Namaste in the context of deity worship, scholars conclude,[38][39] has the same function as in greeting a guest or anyone else. It expresses politeness, courtesy, honor, and hospitality from one person to the other. It is used in goodbyes as well. This is sometimes expressed, in ancient Hindu scriptures such as Taittiriya Upanishad, as Atithi Devo Bhava (literally, treat the guest like a god).[40][41]

Namaste is one of the six forms of pranama, and in parts of India these terms are used synonymously.[42][43]

Since Namaste is a non-contact form of greeting, Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu suggested using the gesture as an alternative to hand shaking during the 2020 Coronavirus pandemic as a means to prevent the spread of the virus.[44]

A side view of a Hindu man in Namaste pose.

A side view of a Hindu man in Namaste pose. The ninth line from top, last word in the Rigveda manuscript above is namas in the sense of "reverential worship".

The ninth line from top, last word in the Rigveda manuscript above is namas in the sense of "reverential worship". Statue with Namaste pose in a Thai temple.

Statue with Namaste pose in a Thai temple.

See also

- Culture of India

- Pranāma

- Sat Sri Akal

- Gassho

- Sampeah

- Wai

References

- K V Singh (2015). Hindu Rites and Rituals: Origins and Meanings. Penguin Books. pp. 123–124. ISBN 978-0143425106. Archived from the original on 2019-12-17. Retrieved 2017-05-20.

- Sanskrit English Disctionary Archived 2016-08-23 at the Wayback Machine University of Koeln, Germany

- Constance Jones and James D. Ryan, Encyclopedia of Hinduism, ISBN 978-0-8160-5458-9, p. 302

- Chatterjee, Gautam (2001), Sacred Hindu Symbols, Abhinav Publications, pp. 47–48, ISBN 9788170173977, archived from the original on 2017-01-11, retrieved 2017-12-28.

- "How Namaste Flew Away From Us".

- Thomas Burrow, The Sanskrit Language, pp. 263–268

- Thomas Burrow, The Sanskrit Language, pp. 100–102

- Namah Archived 2014-08-27 at the Wayback Machine Sanskrit Dictionary

- "उदीर्ष्वातो विश्वावसो नमसेळा महे त्वा । अन्यामिच्छ प्रफर्व्यं सं जायां पत्या सृज ॥२२॥, Griffith translates it as, "Rise up from hence, Visvavasu, with reverence we worship thee. Seek thou another willing maid, and with her husband leave the bride; RV, Griffith, Wikisource Archived 2020-01-05 at the Wayback Machine; other instances include RV 9.11.6 and many other Vedic texts; for a detailed list, see Maurice Bloomfield, Vedic Concordance Archived 2019-03-31 at the Wayback Machine, Harvard University Press

- Monier Monier-Williams, Sanskrit-English Dictionary with Etymology Namas Archived 2019-05-18 at the Wayback Machine, Oxford University Press, p. 528

- namas Archived 2018-10-06 at the Wayback Machine, Monier-Williams Sanskrit-English Dictionary 1899 edition], Harvard University update (2008)

- RV 8.75.10, Wikisource:

नमस्ते अग्न ओजसे गृणन्ति देव कृष्टयः ।

Translation: "Homage to your power, Agni! The separate peoples hymn you, o god."

Translators: Stephanie Jamison & Joel Brereton (2014), The Rigveda, Volume 2 of three, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-01-99363-780, p. 1172 - Maurice Bloomfield, Vedic Concordance Archived 2019-03-31 at the Wayback Machine, Harvard University Press, pp. 532–533

- A. K. Krishna Nambiar (1979). Namaste: Its Philosophy and Significance in Indian Culture. pp. vii–viii with listed pages. OCLC 654838066. Archived from the original on 2020-01-01. Retrieved 2018-11-02.

- "Cologne Digital Sanskrit Lexicon", Cologne Digital Sanskrit Dictionaries (search results), University of Cologne, archived from the original on September 25, 2013, retrieved March 24, 2012.

- Namaste Archived 2014-03-02 at the Wayback Machine Douglas Harper, Etymology Dictionary

- Ying, Y. W., Coombs, M., & Lee, P. A. (1999), "Family intergenerational relationship of Asian American adolescents", Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 5(4), pp. 350–363

- Lawrence, J. D. (2007), "The Boundaries of Faith: A Journey in India", Homily Service, 41(2), pp. 1–3

- Oxhandler, Holly (2017). "Namaste Theory: A Quantitative Grounded Theory on Religion and Spirituality in Mental Health Treatment". Religions. 8 (9): 168. doi:10.3390/rel8090168.

- Yamamoto, Luci (21 January 2019). "Ending yoga classes with 'namaste'".

- Sharma & Sharma (2004), Panorama of Harappan Civilization, ISBN 978-8174790576, Kaveri Books, p. 129

- "Origins of Hinduism" Archived 2014-02-26 at the Wayback Machine. Hinduism Today, Volume 7, Issue 2 (April/May/June), Chapter 1, p. 3

- Seated Male in Namaskar pose Archived 2014-02-23 at the Wayback Machine National Museum, New Delhi, India (2012)

- S Kalyanaraman, Indus Script Cipher: Hieroglyphs of Indian Linguistic Area, ISBN 978-0982897102, pp. 234–236

- Rea, Shiva (12 March 2018) [2007]. "For Beginners: Anjali Mudra". Yoga Journal. Archived from the original on 11 June 2009.

- "Salutation Seal". Yoga Journal. 15 May 2017 [2007]. Archived from the original on 22 July 2014. Retrieved 28 October 2019.

- "Low Lunge". Yoga Journal. Archived from the original on 2009-04-04. Retrieved 2009-06-12.

- "Monkey Pose". Yoga Journal. Archived from the original on 2009-04-04. Retrieved 2009-06-12.

- "Garland Pose". Yoga Journal. Archived from the original on 2009-03-27. Retrieved 2009-06-12.

- "Fish Pose". Yoga Journal. Archived from the original on 18 June 2009. Retrieved 2009-06-12.

- "Wide-Legged Forward Bend". Yoga Journal. Archived from the original on 11 June 2009. Retrieved 2009-06-12.

- "Pigeon Pose". Yoga Journal. Archived from the original on 2014-09-26. Retrieved 2009-06-12.

- "Mountain Pose". Yoga Journal. Archived from the original on 2009-07-22. Retrieved 2009-06-12.

- "Upward Salute". Yoga Journal. Archived from the original on 2009-02-26. Retrieved 2009-06-12.

- "Warrior I". Yoga Journal. Archived from the original on 31 May 2009. Retrieved 2009-06-12.

- "Tree Pose". Yoga Journal. Archived from the original on 2 May 2009. Retrieved 2009-06-12.

- Joseph Shaules (2007), Deep Culture: The Hidden Challenges of Global Living, ISBN 978-1847690166, pp. 68–70

- James Lochtefeld, The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Hinduism, Volume 2, ISBN 0-8239-2287-1, 720 pp.

- Fuller, C. J. (2004), The Camphor Flame: Popular Hinduism and Society in India, Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, pp. 66–70, ISBN 978-0-691-12048-5

- Kelkar (2010), A Vedic approach to measurement of service quality, Services Marketing Quarterly, 31(4), 420–433

- Roberto De Nobili, Preaching Wisdom to the Wise: Three Treatises, ISBN 978-1880810378, p. 132

- R.R. Mehrotra (1995), How to be polite in Indian English, International Journal of the Sociology of Language. Volume 116, Issue 1, pp. 99–110

- G. Chatterjee (2003), Sacred Hindu Symbols, ISBN 978-8170173977, pp. 47–49

- "Greet the Indian way: Israeli PM urges citizens to adopt 'Namaste' instead of handshakes to avoid COVID-19". www.timesnownews.com. Archived from the original on 2020-03-12. Retrieved 2020-03-29.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Namaste. |

| Look up namaste in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

- The meaning of Namaste Yoga Journal

- Modes of Greetings in Kashmiri, Indian Institute of Language Studies

- Ancient Indus Valley Seal print showing Namaste/anjali mudra, CSU Chico